Happy Sunday! This is a very special edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter.

The article you’re about to read went into the works in mid-2023. An Australian writer, David Mahler, was looking to do a piece for us. In that conversation, an exciting topic came up: a little-known Disney feature, canceled in the 2000s, called Fraidy Cat.

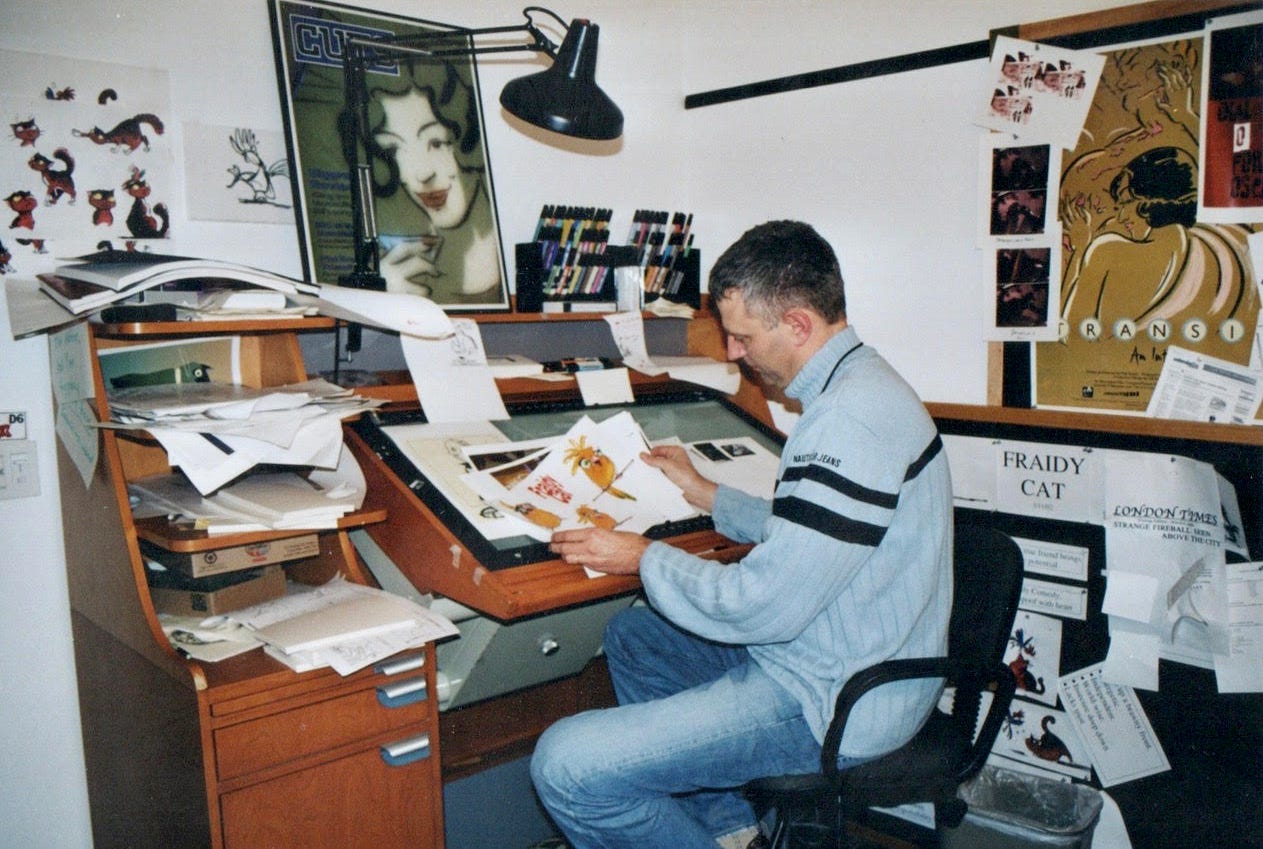

After months of scheduling, David traveled to meet with Fraidy Cat’s original director, Piet Kroon — who now lives in the Netherlands. They spoke for roughly five hours.

What David uncovered is a tale of art, ambition, the Hollywood process, studio politics and a time of change at Disney, as it moved from its 2D era into its modern one. More than that, it’s about the passion of a director who tried to make something good.

David went above and beyond with this project, working with us through round after round of revisions. The article he’s created is our longest to date. It’s one of our favorites we’ve had the honor to publish. For Gmail users, it may get clipped partway — you can always read it without interruption on our site.

With that, we cede the floor to David.

Pet Peeves – Who Killed Fraidy Cat?

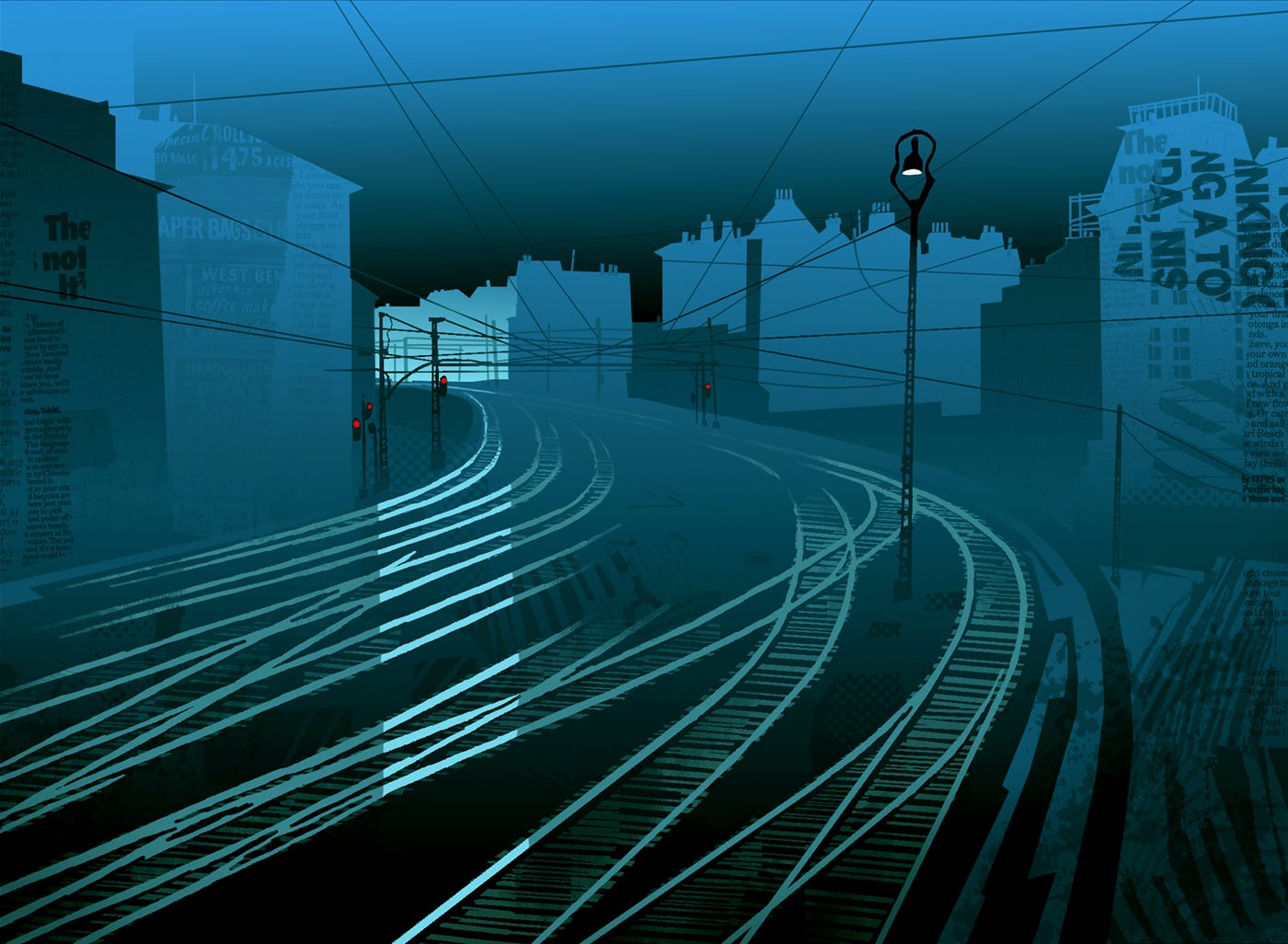

What more can be said about the shelved animated feature Fraidy Cat? There are enough anecdotes and concept images floating around to confirm its existence, a visually experimental and darkly atmospheric tale set in a world of Hitchcock tropes — mistaken identities, femmes fatales, fog-drenched train yards and foreboding docks. And talking pets, of course. This is Disney after all.

The project pops up every now and then, documented through the 2010s by the few staff involved who dared to share their work online, and echoed in more recent years by YouTube videos and blog posts with such salacious titles as “The Canceled Disney Version of Flushed Away” and “Another Disney Movie Disney Missed Out On.” Unfortunately, these recaps don’t have all the details.

For instance, no, director Piet Kroon didn’t come up with the story. How would I know? Well, he told me.

I was very grateful to be invited to the Kroons’ new home, hidden away in a charming Dutch town not too far from Nijmegen. He and I had met during my master’s studies, when he blew the class away with a career retrospective and storyboard workshop, including a breakdown of his Mission: Impossible prison escape scene from Shrek 2. I was in town with a mission of my own, prompted by editor John of Animation Obsessive to uncover the untold history of a lost Disney production.1

After a stroll to the market for some herring and cheese (I love Europe) and a scrumptious lunch with the family, it was time to dive into things.

We moved from the dining table into the living room, to admire a few pieces of production art. Between Osmosis Jones maquettes and a retro-styled Iron Giant poster hung one of Hans Bacher’s pieces from the development of Fraidy Cat.

DAVID: Do you remember who came up with it?

PIET: I actually don’t. Maybe Chris Jenkins did? He was at Disney for a long time, and he went on to work at Sony, I think as a producer, on Surf’s Up. … I don’t even know if it was called Fraidy Cat when I first read it. Maybe it had a different name back then. But it was a treatment. I don’t think it was Chris Jenkins’ treatment necessarily, but I do know that he was interested and, in his bid to become a director at Disney, had written some notes on it. … So I developed Fraidy Cat for like two and a half years, and then ultimately, I like to say I developed myself out of the door.2

Rumor has it Fraidy Cat was a hot property within the studio at the time, well received in each pitch presentation and seemingly on track for a green light. The tale of a tubby tabby cat, Oscar, forced to go on the run à la North by Northwest when he’s unjustly accused of swallowing a bird who’d suddenly flown in the window, a bird who just so happens to be… a spy! Or an amnesiac. Or a femme fatale?

The reports vary, and that would be because the film went through two long, separate development periods, first with Piet Kroon and a rotating roster of writers, and later with Disney vets John Musker and Ron Clements. We won’t be getting into Musker and Clements’ take here — that’s a story for another day, a coda of sorts.

Where does this story actually begin? How did a self-described “tall Dutch dude” with no connection to Disney find himself there as a fresh director in development, given the time, space and encouragement to craft what by all accounts was a highly regarded project over nearly three years of pre-production… only for everyone’s hard work to be put up on a shelf, with (some say) tens of millions of dollars down the drain?

Piet had just bounced from Warner after his co-directorial debut, the cult-beloved Osmosis Jones (2001), failed to make a splash. He’d been in the US for some time already, tapped back in the mid-1990s to help herald Warner Bros. Feature Animation’s slate of films, among them The Iron Giant (1999). By then, Piet had already worked in London on Fievel Goes West (1991), contributed to The Water People by Dutch storyteller Paul Driessen and created his own brilliant short-form debut DaDA.3

While Osmosis Jones hadn’t matched the returns of WB’s earlier hybrid hit Space Jam, Piet’s contributions and ensuing credibility were enough to catch the eye of Disney’s hiring squad. After a six-month sojourn at DreamWorks, storyboarding on Shrek 2, he was pulled into Disney towards the end of 2001.

PIET: I pitched a few of my personal ideas, but they didn’t go for that. But they told me to just look into properties they already had, and if there was anything I liked, I could make a play for it, and maybe get assigned to it, and that’s how I found Fraidy Cat.

Soon, Piet got himself paired with the legendary art director Hans Bacher (Mulan) to develop this Fraidy Cat idea. “First off,” Piet says, “I wrote the first draft of the screenplay. And that was exceptional for Disney because basically I just sat in an office and I was typing and working with Hans Bacher and a small team of people.”

As Piet explains the project, it becomes clear that the history of Fraidy Cat is a history of layers, of versions. It was a film in development that transformed many times, in ways both sweeping and minuscule. One thing which grows obvious was his commitment to it.

“I literally didn’t have time to do anything [else],” he says. “It was just a singular focus on this thing … I couldn’t see a cat without studying it, how they move.”

To get an understanding of how dramatically things shifted over the years, I asked for as detailed a summary as he could muster of his first version, the original version of the story, developed before revisions tore it away.

PIET: There’s this cat, who’s modeled after Hugh Grant. He’s very insecure — he’s a Fraidy Cat. And he lives in this apartment with his owner, a girl called Doris, and they have a landlady who has a strict rule about not having pets. And she’s got two goldfish and a cat. So, every now and again when the landlady shows up with her little dog (who’s sniffing around constantly like, “Is there an animal here?”), Oscar has to hide and lay low, because he’s not supposed to be there and he’s afraid to go outside. These two goldfish are his best buddies, but of course they’re in a bowl, so they can’t do anything. Everything they want to have happen, they have to talk Oscar into doing it. …

And one night this little bird Rebecca flies into the apartment and lands. They find her, and she’s completely confused. She doesn’t know where she is, who she is. Oscar goes to take her to Doris, his owner. So, in the middle of the night, he shows up on her bed with this little bird in his mouth, and she freaks out. Like, “What are you doing Oscar?!” … She has to go to work, and she puts the little bird under a waste paper basket, like a cage kind of thing with books on top, and the bird’s completely loopy. It’s like… amnesia meets Tourette’s, basically.

Because she’s a parrot, she keeps inadvertently blurting out lines she’s learned from former owners. That was part of my probably-too-complicated idea, that as an audience you’d be intrigued, like, “What the hell? What’s she talking about?” And you’d slowly begin to piece it together. “Okay, she used to be in a barber shop or in a kitchen, because she has all these expressions that have to do with cooking, or cutting hair, or whatever.”

But of course the goldfish and Oscar don’t know what the hell she’s talking about. And she’s very shrewd; she understands enough that she shouldn’t be there and she wants to get out, but they don’t want to help her. She fakes her own death or something in that cage, causing Oscar to try and help her, and then she escapes. And there’s a lot of feathers flying and big to-do.

Anyway, when Doris shows up at home, for all intents and purposes it looks like Oscar ate the bird. Because he’s got feathers in his mouth. And she’s accompanied by a guy she met outside who’s looking for a little lost bird. That’s kind of a mystery man. And so Oscar escapes. He’s joined by a real nice character, called Frenzy (another Hitchcock lift), a housefly who fancies himself to be a pet. Oscar has to prove his innocence. He has to go out into this scary wide world he’s never been into, track this little bird down, bring her back safely, to prove that he didn’t eat her, and then maybe life can get back to normal again.

That’s the whole sort of simple engine of the story. Classic Hitchcock: a wrongly accused hero has to prove his innocence.

In the second act Oscar finds Rebecca. She wants to find her real owner. They strike a deal. “You help me find my owner, then I’ll help you clear your name.” Things get complicated, possibly too complicated for their own good, but in the end Oscar overcomes his fears and heads for a textbook happy Disney ending.

By this point we’ve taken our seats on the living room’s L-shaped couch, Piet sunk back and reminiscing on one side, myself perched forward on the other to inhale every detail. With Hans Bacher’s mock-poster for “Birdy” in the background, Piet’s words transform into a shadow play of sorts, the silhouetted characters careening through the initial pitch.

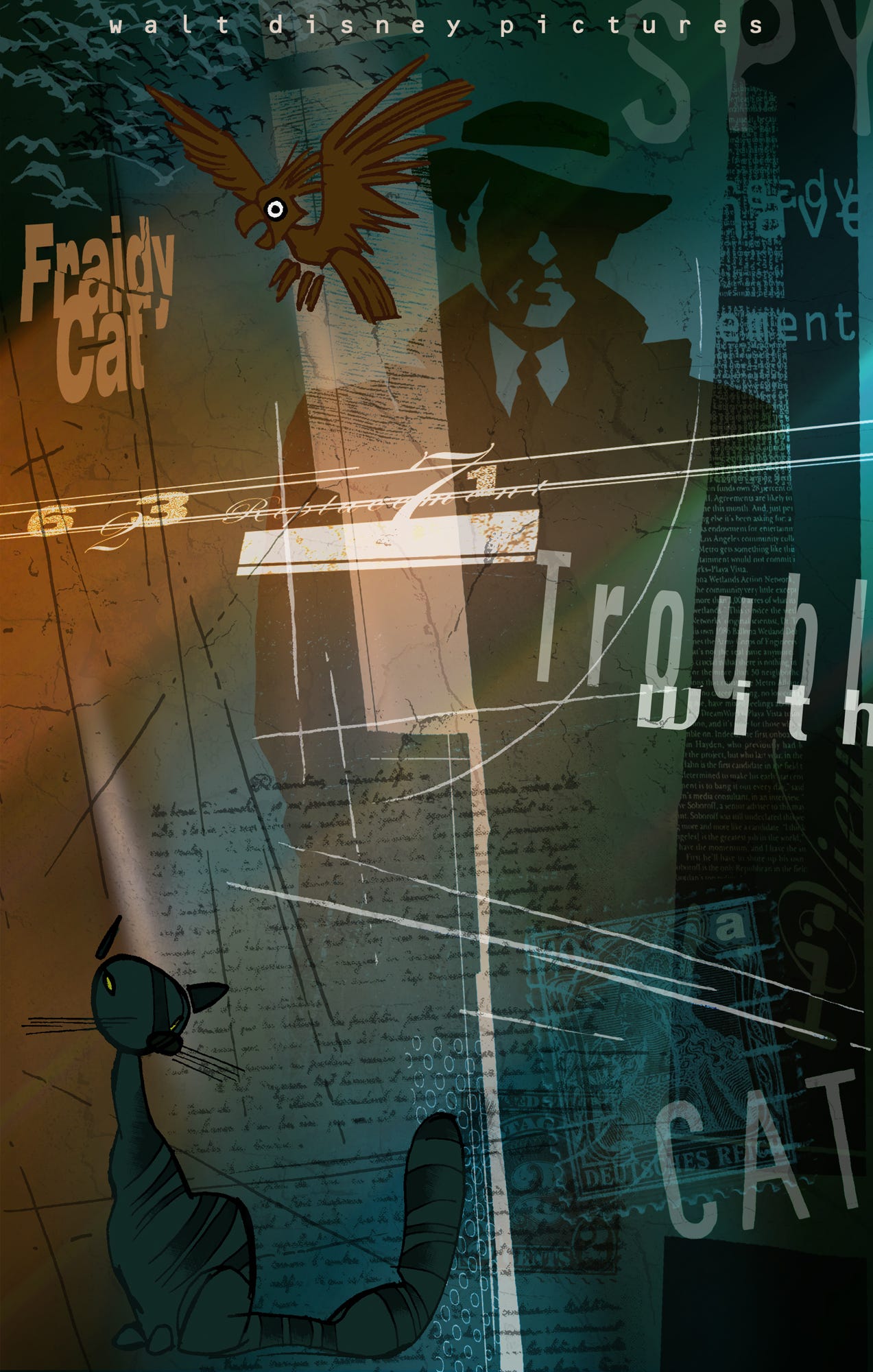

In the past, Bacher has noted that the pitch’s original writer was “not too well known” — but that he himself had been working on the project since 2000, when the higher-ups handed him a three-page treatment to play with.4 In his book Dream Worlds (2008), Bacher explained, “The story outline and the first treatment looked promising. It was a little bit of a Hitchcock crime story about a cat and a parrot in London. Somehow, it reminded me of 101 Dalmatians.” His masterful digital illustrations, included in the book beside his words, tease what could’ve been a daring turn for the studio.

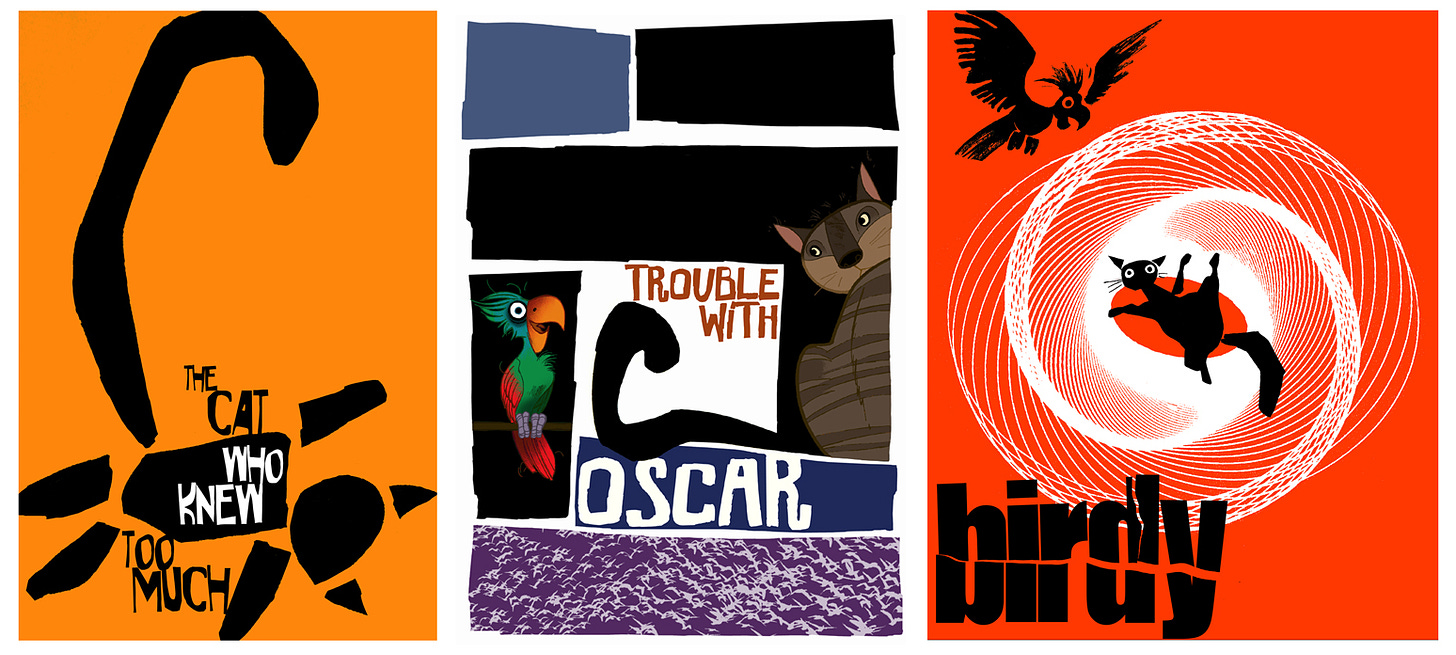

Bacher occasionally reflects on Fraidy Cat on his blog, even sharing his poster mock-ups, spoofs of Hitchcock films and their iconic Saul Bass poster designs (Dial O for Oscar, The Cat Who Knew Too Much). But the juiciest info lies in a 2013 post, wherein he laid bare a disaster in the making. The management of the time was happy to throw six or seven story artists at any one scene, subjecting the writing and concept to a process of dilution. It was, he argued, the “systematic destruction of a good idea.”

Piet isn’t as negative about the situation. “The boards brought the characters into focus, explored the fun of scenes,” he argues. Well before he’d finished his screenplay, the story artists were busily building upon his ideas. “If anything, in retrospect,” he adds, “it might have been better to hold off on the boarding until the entire screenplay was done.”

But what’s certain is that revisions did, over time, become a point of contention for Fraidy Cat.

Pam Coats, a senior exec of development, had been impressed by Piet’s first take on the film. “I’d written the screenplay, I turned it in to Pam Coats… and she told me it was one of the best first drafts she’d ever read of any screenplay,” Piet tells me. “And I’m like, ‘Okay, that’s good.’ ”

Sometimes, executives in Hollywood like a project so much that they decide to change it.

PIET: They wanted me to become more of a director and less of a writer. They wanted to bring in a different writer to do a second pass on the script. And then you work with creative executives — in my case, it was two women who were both named Karen, who’d hired me away from DreamWorks. So they were my sort of buddies in a sense, or they believed in me. They guided this whole process and they told me, “Piet, we’re going to hire a young writer named Anna to write on the movie.” If I didn’t like the direction she was taking it in, all I needed to do was tell them, and they would find somebody else.

And I understand, the whole process is about plussing it, making the material get better. But if you’ve written something, and somebody comes in and writes something else, and it kind of turns muddy, or it gets fuzzy, or it just gets weaker, it’s hard to let that happen.

I resisted that writer. … This is where I think I made one of my mistakes. I took these creative executives up on their word, telling them, “I’m really not happy with the new pages, I don’t really see it going the right way, and you had said that if I didn’t like it we would look for another writer.” In voicing that I sort of exposed them. If they brought in the wrong person, that reflects badly on them. …

DAVID: You came in and rocked that boat.

PIET: Right, and I became a little bit of a problem. So, the one writer went away, and they hired Marco Schnabel, who was actually a pretty good writer. He came up with nice ideas and simplifications, and the project changed. It wasn’t easy; at this point I was still wrapping up the edit for the first act of my script. But they were good changes: a different spin. The idea of Rebecca's amnesia was dropped, but overall the story very much remained true to my original concept: a fun Hitchcock-meets-Disney romp. Before he was able to finish his draft, Marco left to direct Kicking and Screaming, the Will Ferrell feature.

Schnabel’s contributions seem an attempt at streamlining, stripping back the complicated amnesia subplot in favor of the Rebecca character’s becoming a confident, fast-talking spy. One can see the logic from a Hollywood writer’s perspective, a classic foil to Oscar’s neuroses.

Despite doing his best to go with the flow, however, it appeared Piet’s Disney honeymoon was over. Marco’s arrival roughly coincided with an effort to take this troublesome director out of the picture.

PIET: … there was an attempt to lay me off. I think there was concern that I stood in the way of change. I argued I was on board with all the changes. I understood the process. Lord knows, on Osmosis Jones the story had gone through many, many changes. Every movie I’d worked on you had to navigate change. And I guess that swayed Pam Coats to not send me packing there and then and give me another chance.

For now, his extended tenure on the Fraidy Cat project would continue.

Alongside Piet and Bacher and Schnabel in developing Fraidy Cat was a cast of artists. One might understand Bacher’s frustration in seeing a brilliant pitch watered down, but in fact Piet had a number of positive things to share about the story contributors. He singles out Stephan Frank (“a good friend of mine”), Kevin Deters and Ed Gombert (both “really good”) and Stevie Wermer.5

“Stevie was particularly good with emotional stuff, she handled scenes between Oscar and his owner, very sweet scenes,” Piet says. “Every story artist was cast to his or her strengths. Veteran Ed Gombert worked wonders to bring out Oscar’s OCD paranoia. Chris Ure brought the crazy.”

PIET: That was pretty much the core story crew. It wasn’t too big because the film was in development still. In production, there can be 12 story artists or more. I did a lot of boards myself as well. And I directed animatics. We had people from around the studio who did the voices. Joe White, an incredibly funny guy, did a lot of them. Did the temp voice of Oscar, and in doing so also helped me to discover what’s funny about this character. And then the story artist Mark Walton. Very funny guy, great at doing voices. He ultimately was the voice of the little hamster in Bolt who’s stuck in the ball. He did a bunch of voices for Fraidy Cat.6

The list of crew was beginning to flesh out, and, considering the talent involved, it’s understandable why executives and other studio members may have gravitated towards the project.

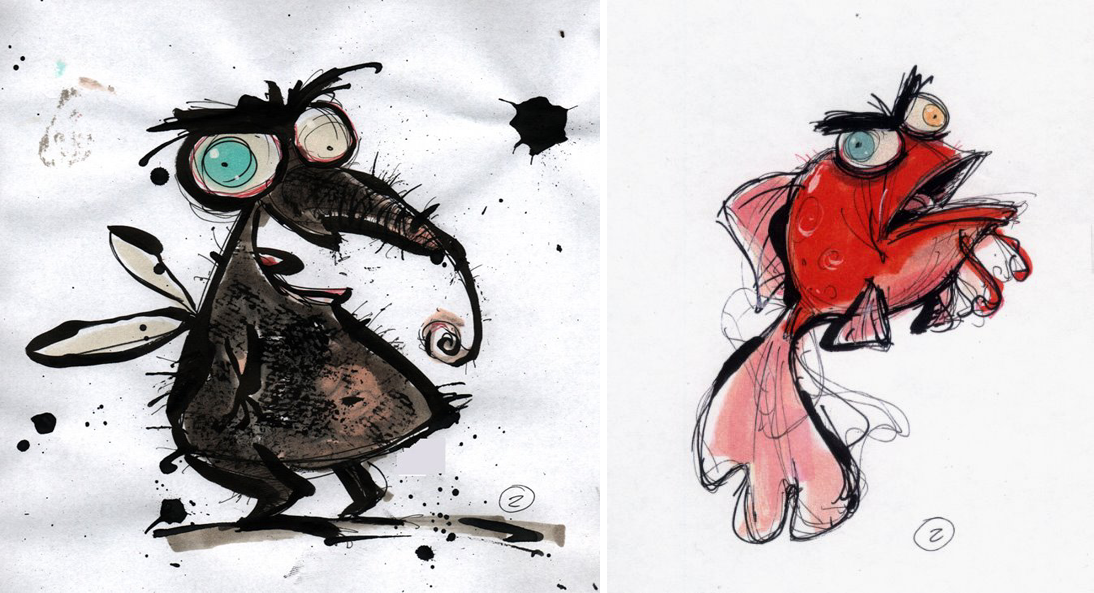

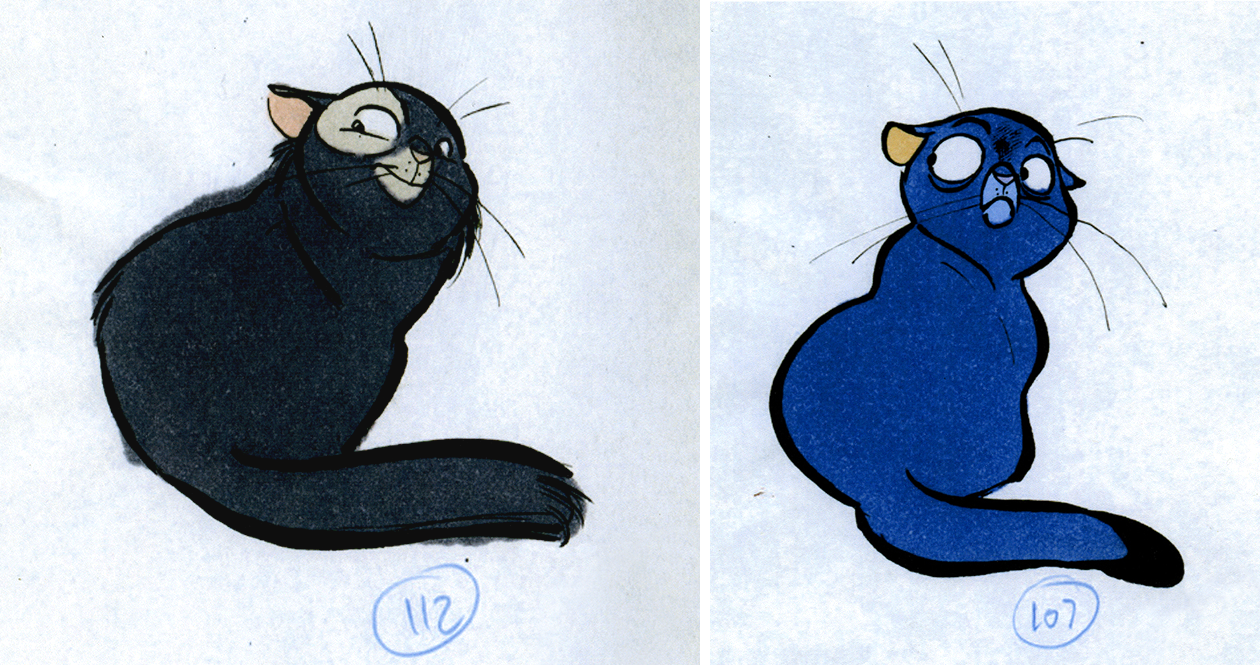

We’re lucky that a number of the artists have shared their work over the years, to an enthused reception. Piet’s Fraidy Cat section of his website highlights a couple alongside Bacher, namely Carter Goodrich and Harald Siepermann. The curated images — Piet’s favorites? — come along with a synopsis of the film as he’d planned it, coalescing to give an impression of what they had in mind.

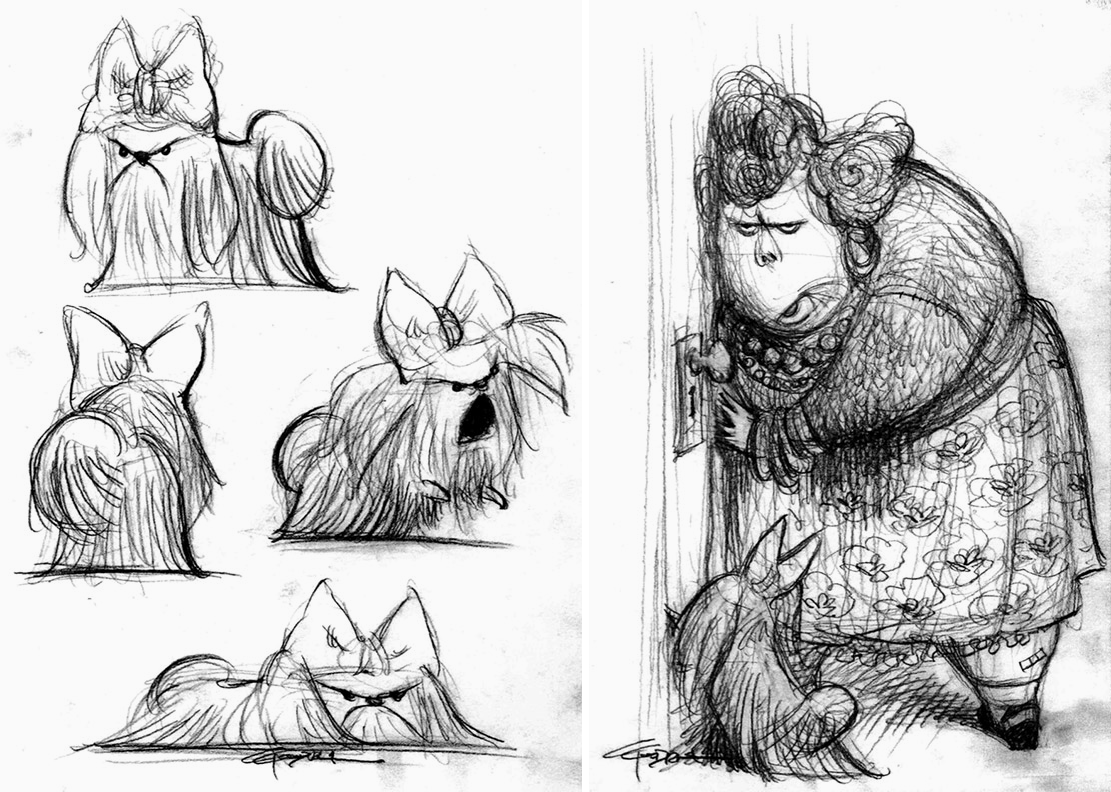

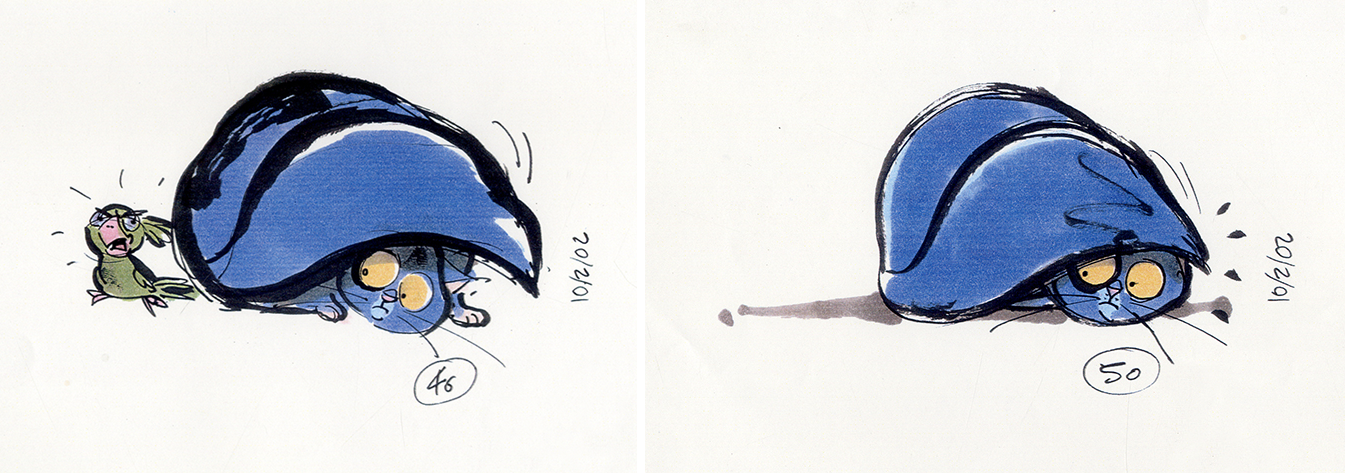

Goodrich’s highly rendered, yet almost cubist, abstractions of people, towering over the animal characters, would be a delight to see lumbering around Bacher’s moody night scenes. Siepermann’s splotchy blue rendition of Oscar is a wonderful shock, and one can imagine him as a vaporous element like something out of Pixar’s Soul, or a more hand-drawn, loose-ink approach à la Princess Kaguya. The potential of the various ingredients is exciting.

PIET: The three top character designers in that era were Peter de Sève, Buck Lewis and Carter Goodrich. They worked on pretty much every feature that was made. Carter is, in my book, easily the most incredible of the three. He has a really nice, original shape language. I loved working with him. One of the ideas I had was to really tell this story from the animals’ point of view. So, if you look at those sketches he did, there was a lot of forced perspective in them. You get really down low with the cat, looking up at this towering human. And, in the overall design, I wanted to sort of push that: build CG characters that had “built-in” perspective distortion. The lower part would be a lot bigger and heavier, and the heads would be small.

More concept art can be found on Rik Maki’s personal website, but his cats are a million miles from what we’ve seen so far. Another version? Could they have been part of the second attempt, the Musker and Clements revisit?

PIET: Rik Maki did a lot of character designs for Fraidy, mostly for secondary characters. He had been at Disney forever. Kind of set in his ways. You kind of knew what to expect. Very charming, funny sketches. All of his designs have, like, little flies buzzing around the heads of the characters … Very nice stuff, in the vein of Ronald Searle, but, you know, it wasn’t exactly what I was looking for.

And what exactly was it Piet was looking for?

An early report on the film, a gossipy letter by entertainment writer Jim Hill circa 2002, confidently declared that there was a fight over what medium Fraidy Cat would ultimately use. The executives, Hill claimed, wanted something that mixed “the very best of the 2D and 3D animation traditions,” whereas Bacher wanted “a straight 3D CG feature.” Hill’s sources seem informed, revealing insider info on departing personnel and incoming director Piet Kroon, the studio’s 3D ambitions, plus the ongoing development of Rapunzel and Snow Queen.

Piet couldn’t recall coming across Hill or his writings in the past, and the idea of a hybrid production seemed like news.

PIET: It was never meant to be a hybrid film. At the time Disney was finishing up Home on the Range and edging towards CG. They had dabbled with it before, like in Treasure Planet there’s Long John Silver, who has a robotic arm which is CG. Work was underway on Chicken Little, their first full-blown CG film. Fraidy Cat was also meant to be CG.

DAVID: And did you want it to be CG? If 2D and storyboarding were your background, were you excited about that?

PIET: I was excited about Hans Bacher’s vis dev for Fraidy. I did love 2D more than 3D. I love that every Disney 2D feature has a distinct look. CG had, and still has, a bland “sameness” to it. Hans was pushing for a very graphic look, a completely new take on CG. Fraidy would have a unique signature look.

Beyond that, I was, I think, probably just excited to be there. If I had put my foot down and said, “This has to be 2D animation,” that’d be going against the times. The studio had decided to transfer into CG. It was really a big upheaval because Disney was this 2D institution, right? And suddenly, all these artists — animators, assistants, in-betweeners, who could draw like crazy — were becoming obsolete. Many animators moved into story, where you could still draw.

There was a lot of uncertainty at the studio, people were looking for security, and I think Fraidy Cat in a weird way was kind of like a rescue vessel. Not just for artists, but also for executives. People were getting on board the Fraidy Cat train, so to speak. Because it seemed like a good bet.

Disney Feature Animation was in a funk, because they were always way ahead of the game. And then suddenly Shrek was cleaning up. And other studios were kind of doing what Disney used to do, and making money with it, and then their own films were dwindling a little bit. And of course Pixar — CGI was getting really big, and Disney was still stuck doing 2D animated films.

A lot has been said in recent years about the proliferation of the “Pixar style,” the homogenization of CG animation, as studios follow what’s worked. But the start of the CGI gold rush was announced with a slew of experimental shorts and tests, with artists and technicians racing to explore the flexibility of new software and the potential it might have for storytelling.

PIET: Bacher was pushing a very graphic style. If you look at the Fraidy Cat artwork that’s in his book Dream Worlds, he was into Photoshop, making his own brushes, and using graphic symbols. So what looks like a bush is, when you look closely, text, fonts basically, and the clouds are not really clouds — he used stamps… all these things are in there. And they make for really nice illustrations.

Theoretically, Fraidy Cat would have been a computer-generated film that didn’t look like a Pixar film. It would’ve had its own visual language so to speak. Of course we had to experiment to see if Hans’ bold ideas would translate to 3D. What should or could characters look like in this graphic universe?

Umesh Shukla, a CG development artist at Disney, worked up test shots with Hans to see if it could actually work. The brushes and graphic elements were great in still images, but as soon as you started to move the camera, they gave themselves away. Like: “Oh, it’s letters, not leaves!” The design would call attention to itself and therefore get in the way of the story.

They were just getting started. I don’t know if it would have ever worked. And I doubt Disney would have had the balls to boldly go where no film had gone before. They were kind of playing defense, looking to catch up with the mainstream. Hans was let go before they cracked the formula. I think that’s part of Hans’ wrath, when he talks about it.

Returning to Dream Worlds, if we flip back from the six pages of Fraidy Cat concept art, we can see how Bacher’s approach was influenced by two prior projects which never made it to the screen. These were the shelved, Florida-set My Peoples, and an unnamed short film conceived with Shukla for the then-in-development Fantasia 2000. Expressive, Pollock-esque paint splashes form the silhouettes of birds, cacophonies of movement and energy. It would have been something to see their abstract forms soar across the screen.7

Alongside the images, Bacher explains, “What we had tried to do was create a marriage between traditional and CG animation, and to create a look using new technology that had been impossible to even dream about some years before.” Ambitious. “We wanted to come up with a new art form.” Lofty! “But, probably it was too much art.” Fair enough, Hans. We all know how execs feel about “art.”

These tech experiments no doubt informed Bacher’s approach to Fraidy Cat, and he continues on the following page, “What I tried to do was a combination of 2D and 3D. Everything was supposed to be built 3-dimensionally, but would look flat in the end. Only a moving camera would reveal that there was an optical illusion.”

You begin to understand the potential Bacher saw in this project when you really hone in and start to notice the little details packed into his illustrations. Decorative motifs, typography and layered patterns evoking a ransom note smeared across a seedy city. The collage effect balances perfectly with the atmosphere and lighting to create a unique style which you can’t help but feel pulled into.

It seems Hill’s source had things confused. Bacher’s avant-garde approach could explain the slight misreporting; it would have been hard to picture at the time. It’s much easier to wrap one’s head around the concept these days after the groundbreaking aesthetic developments in works such as Klaus, Puss in Boots 2 and Arcane. Perhaps the greatest parallel, albeit with a more contemporary, energetic approach, would be the collage-pop aesthetic of the Spider-Verse films, featuring comic book text and textures both clashing and harmonizing with a CG world and characters.

But, again, the story of Fraidy Cat is a story of versions. It’s not clear that these visual ideas would’ve come to fruition, and Bacher was dropped by Disney amid the film’s development. Whether the foundations he laid could have survived the revision process is an open question. Piet tells me that the film’s style was in flux all the way through: “it never reached a point where I was like, ‘Okay, now we’ve found this secret formula for this character.’ ”

What they had were promising leads.

While the look slowly developed, the story continued its cycle of revision and presentation. Overseeing that was a full-time job in itself, but Piet tells me he had another, uncredited role to perform: navigating the studio politics that continually dogged his film and his Disney career. He got to work on Fraidy Cat for years — but the environment clearly wasn’t always a comfortable one.

“My wife told me — which is a good thing — she told me every day to set aside half an hour to really think on that political chess board,” Piet says. “Like, ‘What’s happening, what should I do, what shouldn’t I do.’ ”

If you’ve seen The Sweatbox (2002), you might imagine how this ends.

PIET: … the politics of Disney were really… very, very, very thick. Like, I would get in my car at night and just pull the knives from my back before I could drive home. It really felt that way.

DAVID: Geez.

PIET: And it was in very stark contrast with Warner’s, where I had directed before. That was a studio always living on its last dying breath. Like, when this film finishes, the whole thing will likely go under. So there were no politics, or very little politics, because what was the point? … Whereas at Disney, one thing was for sure — they were going to stay in this business. Therefore it made sense: you can further yourself and your career.

Growing up, many of us aspiring animators no doubt had a romantic vision of life as a director, pooling together collaborators and swimming in unbridled creativity, all in service of some great opus. So, it might be difficult to accept that most of Piet’s time at Disney was spent in a state of suspicion and anxiety.

PIET: You’re juggling. It’s a juggling act, and if you don’t pay attention to it, you’re gonna drop balls. But in the meantime you have to keep an eye on who’s coming through the door, and what’s that guy doing now, and it’s really hard to split your focus, and your attention.

It was a really hard lesson. I always put the film first, fought for what I believed in, sometimes against my own best interests. That’s something I learned from Brad Bird on Iron Giant. The single biggest power of a director is to walk away. That scares executives, if you’re so strong in your convictions that you’re willing to walk away. I think for many executives the film does not come first. Their main job is to keep their job. What my wife advised me to spend time on, for 30 minutes a day, is what they do all day.

And those executives seemed to be nearing the end of their tethers with Piet. He was well aware of it: “I was becoming a problem, I was sticking to my guns too much.” There were fights, attempts to persuade. To this day, Piet isn’t entirely sure of what transpired, where things went wrong. He remembers his producer Roy Conli as “a very likable guy,” but has never had the chance to ask him “what really happened.”

“It’s a lot of things that happened,” Piet says, “and particularly those sort of political maneuvers that I can only guess at.”

At Disney, regular meetings were scheduled for teams to present (and re-present) their projects-in-development. Creatives were pitted against one another. These so-called “Bake-Offs” were climactic affairs, and each team would go all out to make their project seem like the golden goose, worthy of a green light.

PIET: We had to put up, you know, these big pin boards with artwork to fill the walls, and to create a little bit of a buzz. And we did that for Fraidy Cat, all around, Hans Bacher designed posters and it all went up. The prime real estate was across from the men’s room because that meant that the chief executives, like Tom Schumacher, would come out of the bathroom and see your work.

With the script on to its third writer, an animatic in the works, and a stack of enticing concept art, Fraidy Cat seemed like a sure pick at the latest of these Bake-Offs.

PIET: The 2004 Bake-Off was between three projects: Fraidy Cat, A Day in the Life of Wilbur Robinson and Gnomeo and Juliet. Every day there would be a screening for Michael Eisner, who was at that point still the big head of the entire Disney corporation. So that he could see what was brewing and then pick his favorite, basically. Our screening went well. Afterwards Michael Eisner shook my hand and congratulated me on a very promising film… This was after they’d tried to fire me the first time, so I felt, “Okay, I’m on a little bit safer ground.”

We had a big post-Bake-Off meeting with Pam Coats and other executives. Fraidy Cat was named the most promising project. Wilbur Robinson was storyboarded all the way through, so it was ready to go into production, but it was perceived as still having story issues. Fraidy Cat was sort of two-thirds there: we screened the first two acts. Gnomeo and Juliet just had a first act.

Piet shares an email that Coats sent to Fraidy Cat’s team in early 2004. “MDE [Eisner] and Dick Cook liked the movie, that makes me happy and you all should be proud,” she wrote. “I appreciate the good work that has been done to date … We have a solid structure and a high concept movie that is exciting people. We have a talented team that will take us to the next step.”

In-studio, Fraidy Cat must have been a familiar property by this point, a strong idea allowed to grow and develop to such an advanced point. With the other two films in varying states of shakiness, and the executives’ praise in their ears, the small, committed team surely felt confident.

Unfortunately, in the end, the film wasn’t picked.

PIET: My personal understanding of why Fraidy Cat missed its moment is, Disney decided that weekend, right after the Bake-Off, to close the Florida studio. They had the main studio in Burbank where they were making animated features, and they had a studio in Florida. The Florida studio, I thought, actually made the more interesting films. Mulan and Lilo & Stitch were produced in Florida. Away from LA. … So also away from too much “executive interference.” That may be part of the reason they were able to make really nice films. But Disney had decided to “get with the times” and phase out 2D animation, so they shut the Florida studio down.

DAVID: Brutal.

PIET: I think it was because it wasn’t profitable for them to run two studios. So they were consolidating their efforts in Burbank. And of course when they close a studio, that news is gonna get all over the trades. Variety, The Hollywood Reporter. All these journalists trying to read the tea leaves. What does it mean for the movie business, Disney’s position and the Disney stock? So I think to counteract that fallout the studio decided to greenlight, with a lot of fanfare, their next CG picture. Saying: we are still in business! We are not getting out of the game!

As I remember, literally the day after the Bake-Off — after we had had this meeting where Fraidy Cat was deemed the most, you know, deserving project — I came into work and heard Wilbur Robinson had been greenlit. Wilbur had their whole story up on reels; it was the furthest along. And so Fraidy Cat went on the back burner for a little bit. That’s what I think happened, but I don’t know… this is one of the mysteries of my life.

One can only rock the boat so hard. After nearly three years of committed work, resisting and conceding, collaborating and guiding, Piet’s time in Burbank came to a close.

The new president of WDFA, David Stainton, mentioned Fraidy Cat in an April 2004 article by the Los Angeles Times, hyping the studio’s upcoming features while doing some damage control around Home on the Range’s losses at the box office. He reiterated that the film was to be CG, and highlighted Piet as director, confirming he was still on board by early April.8

In the middle of that month, however, Piet was removed as director. Stainton sent out an email to inform the crew:

This decision was made in the best interest of the movie but was not made lightly: Piet has served the studio well in getting the film to this point. I thank him for this and sincerely wish him all the best.

Be assured that we remain tremendously excited about “Fraidy Cat” and we will continue to develop the project under the leadership of Roy Conli until a new director is brought on board.

So, Pam Coats had fired Piet, who’d then talked his way into a second chance. He went on to impress CEO Eisner at the Bake-Off, and presumably Stainton, who dropped his name to the press. And then Stainton pulled the plug on him. Later, I’m told, Coats herself was fired by Stainton.

PIET: Pam was in a difficult “political” position. She really was the logical choice to run Disney animation after Tom Schumacher left. But instead David Stainton, who’d had a successful run at Disney TV, straight to video, making lots of money for the company, was put in place to head the studio. Pam remained in her position as head of development for a number of years. I think it was sort of an awkward shotgun marriage between Pam and David. A battle of competence, maybe. There is a lot more involved in creating a new story, new characters and a new story universe than in crafting a sequel. There are no numbers to paint by.

Piet was not kidding about the upheaval — could there have been a more chaotic, tumultuous period at the studio? Glen Keane, reportedly the first animator to ever command a million-a-year paycheck, was shuffled off Rapunzel, his dream project, which later morphed into Tangled. Chris Sanders seemed to have a fun follow-up to Lilo & Stitch in the works with American Dog, but it was eventually released without his involvement as Bolt.

PIET: It’s all part of this whole big studio politics. I have a friend who spent, I want to say eight years, maybe more, at Sony as a director in development. He had a project, something to do with space, with rockets, and he went through I don’t know how many different regimes at the studio. Where every time there was a new head of the studio, things had to change because, you know, they were there, they were new, so everything had to be new.

So my friend’s action-comedy project morphed into a serious drama and back. “This can’t have a boy at the center; it needs to be a girl.” And he was sort of able to bend with the times and stick with this project for eight years. In the end, it didn’t get made. It was just shelved. I don’t know if it’s still kicking around, but he’s no longer there.

So my sad story isn’t necessarily… there are a lot of films that never see the light of day. Or they pop up again decades later. Fraidy Cat might still get made, for all I know, when somebody finds it in the archives. Frozen dates back to the early days of Walt Disney.

The balance between art and profit has always been integral to film production. After all, a creative business is still a business. If those pesky Robinsons hadn’t beaten Fraidy Cat in the Bake-Off, sending the production to the back burner, would it have been completed? Or were the lack of merchandisable characters and nostalgia for a bygone filmmaker’s oeuvre too risky, no matter which captain steered the ship?

Eventually, the Fraidy Cat story was picked up and dusted off, not a year after Piet’s second and final dismissal. Ron Clements and John Musker had left Disney for greener pastures after the commercial failure of 2002’s Treasure Planet, but were tempted back to the studio and invited to explore the shelf of stagnant properties. Their time on Fraidy Cat resulted in plot and name changes, another round of promising concept art, and even a presentation at SIGGRAPH 2004. But ultimately — inevitably, it would seem — the spark was extinguished.

PIET: Every now and again I’d run into Ron and John at some function somewhere. As I understand, Disney’s ultimate reason to abandon Fraidy Cat, after five years of development, was: “kids don’t like Hitchcock.”

And my initial pitch for Fraidy Cat had literally been: imagine if Hitchcock had made a Disney film, what would it have been like? Hitchcock was at the core of the pitch. From the get-go the story was going to play on Hitchcock tropes. Oscar, stuck in his apartment, is essentially Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window.

For kids, it would’ve just been a fun film. You didn’t have to be a Hitchcock buff to enjoy the story. But for people who knew their Hitchcock, it would’ve had a lot of fun little Easter eggs.

And five years later, apparently, they say, “Well, kids don’t like Hitchcock.” So what happened? Why didn’t they think of that five years and millions of dollars earlier? Because they told me at some point, during my tenure, that they had already spent $5 million on the development. Not on my paycheck, I’m sorry to say, but still.

While $5 million is a fair ways away from the estimated $50 million figure Bacher dropped in one of his posts, the thought of so much time and so many resources being poured down the drain is hard to grasp. Was there really nothing more to show for it? I had to ask…

PIET: Well, I can show you some stuff on the computer. I don’t have a lot. Some studios where I worked, I came away with lots of artwork. For Disney, they were very sort of…

DAVID: Possessive?

PIET: I have stats of the boards. As far as animatics go, I just have one snippet of the opening of the second coming of Fraidy Cat. Not my original opening, but what became of it [once Marco Schnabel came on board]. Storyboarded mostly by Ed Gombert, who’s, you know, a really good story artist. Every now and then I show it to people.

DAVID: That’s never been released before, has it?

PIET: No. They don’t know I have it, probably.

We move from the living room to Piet’s back office, to his computer, and to a folder on a hard drive labeled “Fraidy Cat.”

Piet managed to save, scan and categorize a trove of production materials — scripts, clips, art and sketches. After scrolling through some fantastic images created by each of the artists we’d discussed, he begins to play what turns out to be a 40-minute animatic of the second proper version he’d overseen, with story changes attributed to Marco Schnabel. The date at the bottom of the low-resolution video is 22/12/2003.

We watch the first twenty minutes or so, Piet chiming in every now and then to highlight a board artist or a scratch voice.

To summarize is a tad difficult. Allusions to Hitchcock films — an opening fairground scene recalling Strangers on a Train, with not one but two background-character Hitchcock cameos. We’re introduced to a chubby, nervous man named Ferguson, who takes part in a seedy exchange in a fairground Tunnel of Love, no doubt alluding to Strangers on a Train’s climax.

Oscar is introduced inside Doris’s apartment, squabbling with a couple of fish who tease him for his chronic phobias. Piet pauses.

PIET: The fish are Bernard and Herman. Bernard Herman was the composer for Hitchcock.

Oscar’s fluttering Hugh Grant persona certainly comes across as he attempts to scale a bookshelf, getting high enough for a Vertigo shot to send him careening to the floor in fright. Rebecca crashes into their world and immediately establishes an air of espionage cool, bordering on paranoia.

Rebecca: “That guy’s been after me ever since I left the coop.”

Oscar: “What coop?”

Rebecca: “If I told you, I’d have to kill you.”

Oscar: “Right. Never mind.”

She’s certainly no amnesiac. Doris’s landlord has become her aunt, gushing over the little bird.

Aunt: “We have to get you in tip-top shape so we can beat Lady Rutherford in the canary competition!”

PIET: It’s no longer the landlady, now she’s like an aunt. Who has a thing for birds and competitions.

Rebecca makes her escape, accidentally framing Oscar, who’s pushed by the buzzing fly Frenzy to go out, track her down and clear his name.

After a Hitchcock caricature rides past on a bicycle, we’re introduced to Mr. Bad Guy, the silhouette from the opening tunnel exchange. Killian. His cat allergy is established with a sneeze, and we’re prepared for it to come up again at a crucial moment — my bets are on act 3.

Oscar makes his way through town, hops on a train after narrowly slipping past Killian, who sneezes. Damn. We’re still in act 1.

Frenzy gets left behind. A shame. He was a fun character, and we only got him for 15 to 20 minutes. Piet skips forwards a bit.

DAVID: You guys got pretty far with it.

PIET: Yeah, well, we had the whole thing finished, pretty much. I think this is the…

He plays a scene where Oscar and Rebecca are in a train car. He’s encouraging Rebecca to sing, and a chorus of sheep in the carriage join in, “Sing, sing, sing!” But she yells, “I don’t! Sing!”

Oscar shuts up at the outburst. Turning to the sheep, he says, “Okay, friends, a big day tomorrow. Let’s get some shuteye.”

Slow string music swells as they go off to opposite sides of the train carriage. Oscar starts counting the sheep (“One, two, three… four…”) and nods off. Rebecca looks remorseful. Piet explains, “They meet up and, you know, it’s dislike, but gradually towards the end they bond and become friends, like they should.”

It must be a bit painful to rewatch it all. But I’m elated at what’s been shared. Just seeing that indeed a story was being workshopped, it was developing — it was real!

Piet reaches under his desk and emerges with a cardboard filing box, lifting the lid to reveal stacks of manila folders branded with the WB Feature Animation logo. We flip through folder after folder, stuffed to the brim with sketches and ephemera. Crew caricatures from the production of Iron Giant, doodles from his time on Shrek 2, concept props and environments for various Blue Sky productions. And stacks of concept art and sketches for Fraidy Cat.

Dozens of variations of Oscar by different artists, plenty of sketches of Rebecca, as a cockatoo, a parrot and a more generic budgerigar. Quite a few feature her with a wing splint made from a popsicle stick, a nice touch. A big black-and-white spread of Oscar sheepishly slinking past a tree, overburdened with glaring… birds. A beat drawing of a great hullabaloo at the London Bird Show. A daring escape in a hot air balloon. Detailed sketches of Doris’s apartment from different angles. He has each of Bacher’s posters: Dial O for Oscar, The Trouble with Oscar…

Somehow, tragically, we reach the end of the stack.

PIET: Well, that concludes our presentation.

In a sense the journey was complete. We returned to the kitchen to finish our now-cold cups of tea, barely noticing that dusk had settled outside. It had been a long day, for both of us, draining in a sense but invigorating in another.

Some questions were still unanswered. For example, who on earth actually came up with the original story treatment? But suddenly there was a long list of names — artists and writers and executives, who might each have a piece of the puzzle to share.

In the following weeks and months, I would reach out to a number of them. While all were happy to reminisce about the film that could have been, sharing little anecdotes about the Bake-Offs and how the production sent waves of interest and excitement through the studio, no one had a solid answer as to who’d planted the initial story seed. Perhaps more perspectives will crop up in the future, to fill in these missing details.

But, for now, I was deeply satisfied to have seen a chunk of a lost Disney film. Perhaps I was the first person outside the studio’s orbit to have ever seen it? I hope I’m not the last.

Piet may not view his experience as unique, but it was apparent from the outset that the whole ordeal had had a lasting personal impact. It was hard not to empathize. He’d seen something special in the story of Fraidy Cat, and his commitment to championing a vision in spite of disputes, studio politics and arbitrary revisions made for a courageous tale.

His dream may not have come true, but he clearly appreciated the chance to try. During our talk, he told me, “I look back fondly on the whole thing, to tell you the truth.”

He seemed to still believe in what he and his team had made all those years ago. Like he put it, “If it doesn’t resonate with anybody I don’t think you can last that long, so that was pretty good.” There was something that people connected with, I said. “Yeah, it was… it was just a fun project,” he replied. “It was going to be, or you know, it still could be a really good film.”

David Mahler is a cartoonist and writer from Melbourne, Australia. His passion for animation was fostered by a childhood spent indulging in equal parts obscure anime, experimental shorts and Golden Age Hollywood. His first graphic novella Deep Park was released in 2013, and, over a decade later, he’s begun work on an overly-ambitious follow-up. Let’s see how that pans out.

Until next time!

I’ll always be grateful to Piet for giving me so much of his time. A massive thank-you to him, and to Carter, Stephan, Mark, Hans and Umesh Shukla. Eternal gratitude to Jules and John who encouraged this adventure into animation history, and particularly for assembling so many resources which were the foundation of this article.

The interview with Piet Kroon took place on November 1, 2023. Some of his answers were revised, with his input, during October 2024.

See “Don’t Quit Your Day Job, Work the Night Shift” (February 1997).

Before talking to Piet, the known roster of people involved in Fraidy Cat was:

Piet Kroon (director, story, concept art)

Hans Bacher (concept artist, likely production designer)

Carter Goodrich (art and design)

Harald Siepermann (art and design)

Rik Maki (art and design)

Umesh Shukla (technical side, likely pipeline development)

After our meeting, the list swelled to include:

Buck Lewis (character designer)

Chris Jenkins (possibly wrote the initial treatment)

Chris Ure (story)

Stephan Franck (story)

Kevin Dieters (story)

Stevie Wermer (story)

Ed Gombert (story)

“Anna” (writer, moved on to Gnomeo and Juliet)

Marco Schnabel (writer)

Mark Henn (animation tests)

Joe Grant (consultant)

Joe White (scratch voices)

Mark Walton (scratch voices)

Roy Conli (producer)

“Karen” and “Karen” (creative execs)

Pam Coats (senior vice president of creative development)

David Stainton (WDFA president, who finally pulled the plug)

Later, after our meeting ended, I reached out to some of Piet’s collaborators. Mark Walton kindly confirmed, “I did scratch voices for the fly, both as a cockney and an American, for different versions of the film.”

Stephan Franck was also happy to reminisce. “I started on it in 2002,” he wrote, “so this was right before the studio became all digital, and it was still a hybrid pipeline.” As he explained in his email:

In those days, you could literally spend years and years of your feature animation career on projects that people would never see. … I was told that Michael Eisner had come to the studio to look at the development slate, and somehow had talked about his family’s cat, and expressed the idea that he would love a cat movie... so, all of a sudden, the studio wanted a cat movie.

Franck’s tale of pitching to Eisner’s sensibilities recalls a rumor that Brother Bear was conceived because the executive opined how many plush toys the company could sell with a “bear movie.” Considering Eisner’s reputation amongst the creative staff, notably documented in The Sweatbox, it might be best to take such rumors with a grain of salt.

In another email, Bacher wrote to me:

I tried to develop a 3D style that had some 101 Dalmatians ingredients, weird textures. All in all a very new look, in a way a further developed Wild Life look. They loved it, so I continued, only my friend Andreas Deja joined shortly and added some great character designs. Man, it would have been a fantastic film.

In later messages, Umesh Shukla explained:

… I was always in touch with Hans, and he said, “Hey, we’re doing this film called Fraidy Cat. So why don’t you come and be more part of the development team?” … So Hans was the designer, right, and it was really flat — a very interesting look we were working on. … Hybrid was a theme Hans and I were constantly talking about. It was always, “How do you create a combination which is not multi-planing, which is kind of a fake, pseudo 3D kind of thing? Then how do you bring that to the characters, the interactions?”

There were a lot of interesting possibilities. You can just imagine: it’s not 2D, it’s not 3D, it’s kind of a beautiful combination of each. You see something and marry it together. Yeah, it would have been good. … In terms of pipeline, we didn’t get that far. … In our case, we were just in the early stages of development, just a small team. It didn’t go to pipeline.

Shukla noted that Pam Coats shouldn’t get too much of the blame for the shutting down of Fraidy Cat:

… it’s not like one person, it’s like a collective decision, you know. So Pam maybe was involved in the decision, but I don’t think she would have been... like it’s just the process, the way it happens. It’s not like one individual driving it.

Mark Walton mentioned that Stainton later “fired Pam” at an unspecified date.

See “Bad Day in the Barnyard” (April 5, 2004).

Glad this film was able to truly come to light through this piece! Would have been cool to see Bacher's infinitely 00's designs come to the screen alongside such a classically inspired story, but glad we're getting to see it here. Some of those designs really reminded me of Disney's short film Lorenzo - don't think there was any actual overlap between the productions but something must have been in the air!

Articles like these always have a bittersweet energy. It's wonderful see the creative passion shine through these previously unseen film art, but quite sad to see it go to the dumps even after millions of dollars have been poured into due to corporate interests changing.