Welcome back to the Animation Obsessive newsletter! Thanks for joining us. Here’s what you’ll find in this week’s edition:

One — looking back at the Soviet Winnie-the-Pooh cartoons.

Two — animation news from all around the world.

Three — the retro ad of the week.

Four — the last word.

As an aside, this is our first new issue since we opened up paid memberships on Saturday. (Welcome to everyone who’s joined so far!) For anyone who missed that update, you can see it right here.

The short version is that we’ve got exciting, weekly bonus issues coming down the pike. They’ll drop each Thursday. If that sounds tempting, you’ll find everything you need on our new and improved subscription page:

If you’re not ready to make the jump, though, you’ll still be able to catch our Sunday newsletter for free each week. Your readership means a lot to us. You can check out the first few bonus posts for free, too, as a special teaser.

Now, here we go!

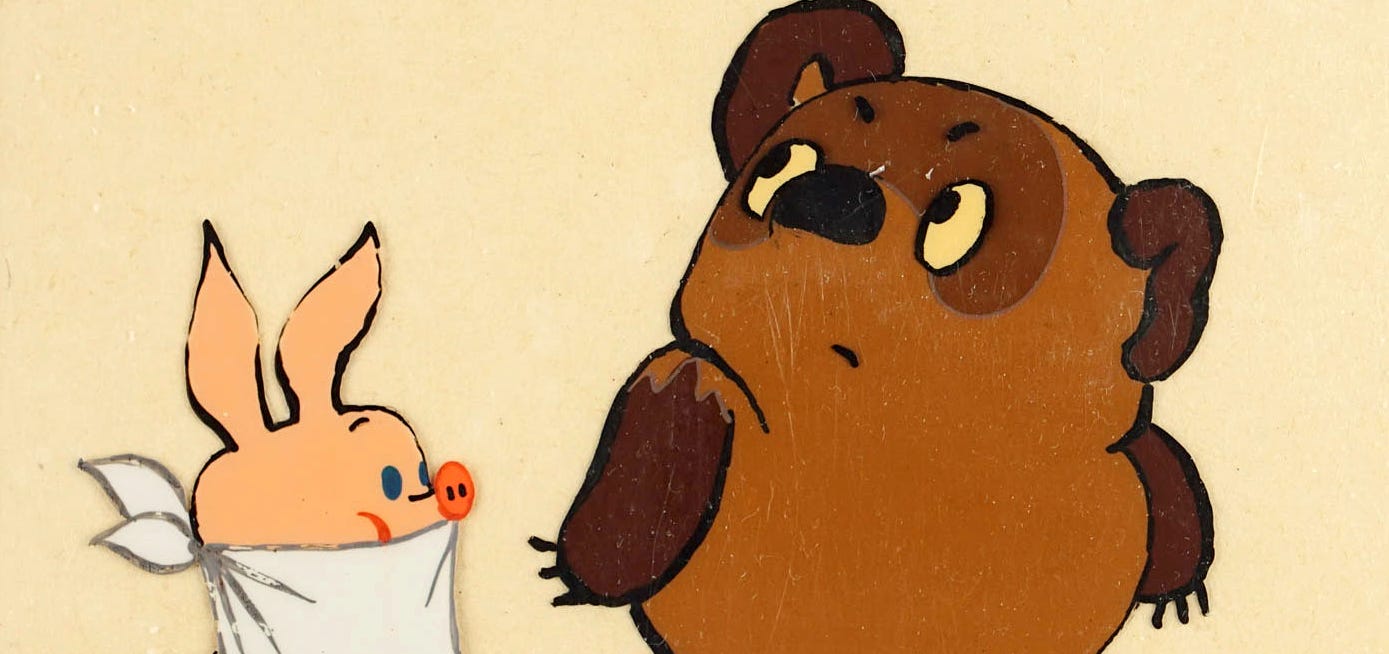

1. Russia’s Winnie-the-Pooh

In Soviet Russia, animation advanced in eras. There was the wild, early stuff that borrowed from modern art. Then, government mandates kept animation realistic and Disney-esque during Stalin’s reign. His death brought an artistic thaw, culminating in a film called The Story of a Crime in 1962.

Rather than Disney, this cartoon looked more like UPA — and it helped to jump-start a revolution in animation. As historian Boris Pavlov later put it, a “symbolic language of images was finally possible.”1

This is the origin of Russia’s iconic Winnie-the-Pooh cartoons. Their director, Fyodor Khitruk, debuted with The Story of a Crime. He got the idea to adapt A. A. Milne’s stories as the ‘60s wore on. Khitruk had read them in English, and then in the Russian translation. He loved them, but he hesitated — putting the project off for years.

“To film the classics […] is always dangerous; there is a risk of falling short, of being below the level of the original,” Khitruk later said.

Khitruk wanted to be ready. It’s the same attitude he’d taken with directing. At Moscow’s state-run Soyuzmultfilm, he’d spent decades as a top animator on films like The Snow Queen. When he finally gave in to the pressure to direct, Khitruk recalled that he “was already 43 years old — an old maid!” Yet that mix of age, skill and vision made him a hero to the generation of young, rebellious animators below him.

It was during his cartoon Film, Film, Film (1968) that he solved the Winnie-the-Pooh problem. Khitruk befriended an artist on the team — newcomer Vladimir Zuikov. He felt that Zuikov had the right spirit to give Milne’s story a “worthy visual incarnation,” which captured the “naive absurdity” of the text better than the original drawings had.

Pooh himself was the first and probably biggest challenge. Eduard Nazarov, one of the art directors on Winnie-the-Pooh, said that Zuikov’s first try was “a completely unimaginable character.” As he put it:

It was not a teddy bear, but a mad dandelion, a creature of ambiguous form: woolen, prickly, as if made from an old mop that had lost its shape. The ears — as if someone had chewed them, but hadn’t had time to eat one of them. But there was something in it! And Khitruk clutched his own head: “Hell, what is this you’ve come up with?!” […] We sat down with this miserable beast, and, in the end, we smoothed him out under Khitruk’s guidance.

Khitruk called their finalized Pooh “a philosopher, a dreamer.” That philosophy, though, is built on the logic of “naive absurdity” that Pooh and his friends use. Christopher Robin was cut from the story for this reason. In the books, his presence sets the toys’ world apart, turning it into an island of nonsense in a wider world of sense.

“For us, it was all one world,” Khitruk said, “the world of Winnie-the-Pooh.”

As one commentator pointed out, the roots of this vision of Winnie-the-Pooh lie in the book’s Russian translation, which minimizes the humans. Still, by removing Christopher entirely, Khitruk took it further than the original translator had intended. This caused a few problems — since that translator had been hired to co-write the screenplay.

Even then, Khitruk said that the writing was the easy part. They mostly stuck to the source material. A bigger problem was the casting — especially Pooh’s. The team ran through a long list of candidates before landing on Yevgeny Leonov, a renowned actor in the USSR.

As Leonov acted out Pooh’s lines, Khitruk was struck by his mannerisms and had the animators copy them. The actor’s voice was too low for the role, though — so they fixed it by speeding up the recording. Khitruk would later argue that the film’s success “to a large extent depended on Leonov.”

It’s said that Leonov is the real source of Pooh’s famously unusual character in these films — his odd movements, his sudden pauses. That was Khitruk’s account, too. But it’s a little simplified. In fact, Nazarov felt that it was Khitruk who most ended up in Pooh:

Everyone says he resembles Leonov. Yes, certainly. But most of all, he resembles Khitruk himself. You just have to look at how he [Khitruk] turns around, how he moves his hands, and how he puts his hands to his head, as if they were paws. Just like Winnie-the-Pooh.

Between ‘69 and ‘72, Khitruk and his team released three Winnie-the-Pooh films, around the time that Disney was doing its own take on the characters an ocean away. Although Khitruk was a Disney fanatic and dubbed Bambi the “pinnacle” of animation, he hadn’t seen Disney’s Pooh while making his own. This helps to explain their wild differences.

Later, during his first visit to Disney’s studio, Khitruk played his Winnie-the-Pooh for the animators. In a documentary from the late ‘90s, Khitruk could still barely contain himself as he told the story. “Woolie Reitherman [...] said: ‘You know, your Winnie is better than mine,’ ” Khitruk remembered. “That’s the highest award I have ever received.”

Khitruk’s Winnie-the-Pooh films hold up as some of the best cartoons of their era. They may not have had the instant visual impact on Soviet animation that The Story of a Crime did — but their timing, writing and sensibility became part of the canon. In Russia, there are pre- and post-Pooh cartoons. They’re more iconic in their country than Disney’s Pooh films are in America.

In retrospect, Khitruk attributed it all to the books. His films, he said, were just transporting the magic of the original stories to the screen in some small way:

The book is very philosophical. But it's a very refined, ironic philosophy, the kind that is only bestowed on two categories of people: the very small ones, that is to say, the children, and very old people. […] I tried to recreate the atmosphere of this book. To a certain extent, I succeeded. And perhaps that can explain the success of this film.

You can watch Khitruk’s three Winnie-the-Pooh films with English subtitles via Animatsiya, a site run by the veteran translator Niffiwan. Find them here, here and here.

2. News around the world

Soyuzmultparks reveal a Russian studio’s ambition

It’s been a busy few years for Soyuzmultfilm. Under new management, the Moscow-based studio has expanded, rebranded and pushed toward privatization. Just last week, it became a joint-stock company. The government revealed its plan to sell three-fourths of Soyuzmultfilm’s shares to the public.

This week, TASS reported that Soyuzmultfilm will open new “Soyuzmultparks” in the Russian cities of Kazan, Perm and Gelendzhik — starting later this year. Each park is a multimedia center based on Soyuzmultfilm’s history and characters. They double as educational hubs, helping to spread the animation industry across Russia. The first one launched in Moscow during February 2021.

The Russian government has been dumping money into creative industries in recent years. One of the major goals is to decentralize animation away from Moscow to boost growth. Soyuzmultfilm, which has spent most of the year investing in animation development across the country, is playing a big role. Soyuzmultparks are the latest step.

Politics are at play here, too. On Wednesday, Putin praised Soyuzmultfilm’s contributions to “national culture and art.” The studio is being held up as Russia’s Disney — and a monolith of Russian values. At the same time, Soyuzmultfilm has been shoring up its brand by downplaying the individual artists who made its classics. Last year, animator Yuri Norstein leveled a broadside against the studio for just this reason.

Despite the pandemic, anime’s mad rush continues

In Japan, the COVID-19 pandemic is worse than ever — and it’s reached the anime industry. As we wrote last week, a host of people connected to anime have contracted the virus, including Pom Poko voice actor Makoto Nonomura. (He was just released from the hospital.)

And yet the industry hasn’t hit the brakes. In a few widely-reported tweets, the anime director Takashi Watanabe wrote that studios are still going — even as some of them run into massive outbreaks. Those outbreaks are then, again and again, kept under wraps. He expressed outrage that the threat of COVID-19 to workers wasn’t being addressed.

“Will they not understand unless animation workers start dying one after another?” Watanabe asked, per a translation by Anime News Network.

Meanwhile, though, the popularity of anime is setting records around the world. Recent data from Parrot Analytics suggests that “global anime consumption has nearly doubled since 2017,” Variety reported this week. And Parrot claims that demand is still outstripping supply — creating more pressure for more anime.

When you toss in Teikoku Databank’s data report earlier this month, which revealed that the anime production industry actually shrank in 2020, things look even darker. The industry is trapped between the push to produce more anime and the reality that more anime can’t be produced without crumbling the industry at its foundations.

Best of the rest

Actor Ed Asner, who voiced Carl in Up, passed away today. He’d just reprised that role for Dug Days, a series unveiled on Thursday. Asner was 91.

The trailer for the American series Maya and the Three, the ambitious collaboration between Jorge Gutierrez and Netflix, dropped on Tuesday.

Also in America, Chromosphere launched a new series called Yuki 7, per Catsuka. See its first episode on YouTube.

On Wednesday, Cartoon Brew reported that the Croatian cartoon series Professor Balthazar has been restored and officially uploaded to YouTube. (Craig McCracken notes the series’ “huge influence” on Wander Over Yonder.)

Canadian vet Robert Valley won a Primetime Emmy for his production design on Ice, part of the Love, Death & Robots anthology.

The animated series The Legend of Hanuman is burning up India’s charts — a recent report named it the week’s most-streamed film or series in India.

Also in India, Studio Eeksaurus is working on a new film about the historical figure Sri Aurobindo, who fought against the British Empire.

Netflix set dates for Robin Robin and the new Shaun the Sheep Christmas special by Aardman in Britain — they’re due on November 24 and December 3.

Lastly, Pixar’s Luca seems to be another victim of China’s slow box office this summer. Per the Yangcheng Evening News, it’s well behind the numbers that films like Soul and Inside Out posted in the country.

3. Retro ad of the week

Japanese TV commercials have always been more than just Suntory Time. (Although that’s based in reality, too.) Advertising in Japan has its own ruleset. It plays on values and aesthetics in Japanese culture — just as Ford’s rugged-sounding narrator sells pickup trucks in America today.

A good example is Lotte’s ad series for Koume, a hard candy with a sweet-and-sour flavor, infused with Japanese apricot. When Lotte launched it in 1974, it hired artist Seiichi Hayashi to make an animated mascot for the commercials. The idea was to reflect the taste of the candy by portraying a girl’s “sweet-and-sour” first love, Hayashi recently recalled. And so Koume-chan was born.

Inspired by period dramas about girls in love, Hayashi made Koume-chan a nostalgic throwback, kimono and all. “At that time, it was normal for lifestyles and fashion to imitate the West,” he said. There was a sense that Japan needed to catch up. Hayashi struck a chord with the public by doing the opposite. The third Koume-chan spot, in 1975, even made waves at overseas festivals.

It marked another strange turn in Hayashi’s career. Early on, he’d worked at Toei Doga under Isao Takahata. He’d also dabbled in underground manga and anime — like his darkly beautiful Shadow. Among his favorite animated films was The King and the Mockingbird. Hayashi had an artist’s sensibility, yet he stood in the commercial world.

He still walks that line. Hayashi is a respected illustrator and painter with an instantly recognizable style. But he’s worked on the ongoing Koume-chan campaign in varying capacities since the ‘70s. His art is on every package. “So, in effect,” writer Ryan Holmberg once noted, “Hayashi’s artwork can be found almost anywhere in Japan.”

We’ve included one of our favorite Koume-chan spots below. Its date and credits are unclear, but one YouTube comment places it in 1988 — which seems like a reasonable guess:

4. Last word

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading — we’ll be back next Sunday with more.

You won’t have to wait that long for another issue, though. We’re rolling out our first bonus post on Thursday, September 2. It’s a chat with Vaibhav Studios — our favorite animation team in India. We talk process, Lamput, those mega-popular idents and more.

Even if you’re not a member yet, you’ll be able to read the interview on a trial basis. It’s the first of three teasers we’re offering through September 16 — after which Thursday bonus posts will go behind a paywall. Now is a great time to join if you don’t want to miss what we have in store:

Hope to see you again soon!

Pavlov made this comment in the documentary The Spirit of Genius: Fedor Khitruk and His Films, which we use as a source throughout the article. It’s in English, and we highly recommend it.