Happy Sunday! We’re back with another issue of Animation Obsessive, and it goes like this:

1️⃣ Writing an episode of Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends.

2️⃣ Global animation news.

Before we continue — readers power this newsletter, and we’d love for you to join us:

Now, let’s go!

1: Script-driven images

For a certain generation, Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends (2004–2009) is a modern cartoon classic. This series, inspired by stuff like ‘60s psychedelia and The Muppet Show, was one of the best and biggest of its time. It was viewed by Cartoon Network as its ratings “workhorse,” according to Foster’s creator Craig McCracken.

A tiny creative team oversaw the series, which gave it a personal feel. The fingerprints of McCracken and Lauren Faust, who married during production, are all over it.

In 2006, McCracken wrote that there were “not a lot of people with their hands in the pot” on Foster’s. He liked to have it under his own control as much as possible — he didn’t want it to be a show “made by committee.” One tool that helped to keep things close to his vision was screenwriting.

His earlier Powerpuff Girls had been board-driven, in that episodes were drawn as storyboards first, without scripts. Foster’s was script-driven: a screenplay came before the storyboarding stage. The series was guided first and foremost by words.

“I prefer scripts,” McCracken has explained. In his experience, they make revisions easier, which in turn makes it easier to bring a series in line. As he put it, “Scripts give me more control over getting the cartoon I imagined.”1

When Foster’s was underway in the 2000s, McCracken made a series of posts about its script process on an official blog for the show. They were written as it happened, revealing how episodes came together in real time. That blog is still online, but the posts about writing aren’t — by 2008, they’d all been deleted.

Using the Wayback Machine, we’ve unearthed them (see the notes2). Today, we’re discovering what this buried treasure can tell us about the writing of Foster’s.

The foundation of a Foster’s episode was the story meeting. The core group, including McCracken and Faust, gathered to brainstorm. By 2006, the actual Foster’s writing team was just one “in-house writer and a couple of freelance guys that we feed stuff to,” according to McCracken. While developing a story idea, they worked from the characters outward.

“Being a character-driven show, we like to begin with really simple character motivations,” explained one of the rediscovered posts, “and let our characters’ personalities drive what happens in the story instead of trying to build an episode around a ‘concept.’ ”

The story meetings turned these simple ideas into full storylines. There was a careful structure to it all:

Foster’s episodes are 22 minutes long, which breaks down into approximately three 7 minute segments or acts. Once we have a basic story we like, we break the episode down into these acts by putting up index cards that describe the most basic and broad strokes of the story. We shape, sculpt and change these cards over and over till the gags, plot points and character motivations all fit and flow together.

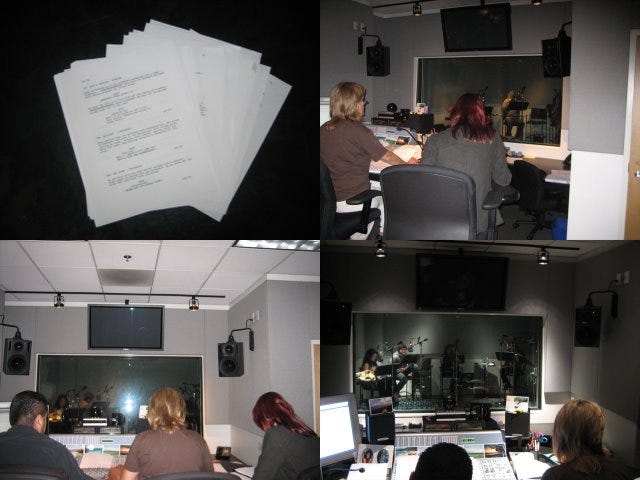

In the photo above, we see the index cards spread out across the wall — clustered under each act of the story.

This led straight to the next stage: per the blog, “the assigned writer … takes all the cards from the meeting and puts them together in an outline.” These were kept short, and they were created mainly as something for Cartoon Network to review and greenlight.

The outline for the Emmy-winning episode Go Goo Go was shared as an example. Across three pages, it gives us the top-line description (The Concept), the core conflicts of the story (The Conflict) and the three-act plot summary (The Story). The section labeled The Concept is just one sentence. It reads, “A girl with an over-active imagination is filling the house up with hundreds and hundreds of friends.”

At the bottom of the outline, there’s a fourth section — given the name The Comedy. Here, the episode’s humor is put across in words. In response to a reader question, Lauren Faust described the comedy section like this:

Outlines are so short, oftentimes there is only room for plot and structure in the 3 act section. So we break down exactly what it is about this show that we hope will make you laugh. We talk about anything ironic, and character quirks that make a situation worse, misunderstandings, amusing character conflicts, running gags and sometimes even specific jokes.

With Go Goo Go, written by Faust, we find a comedy section that isn’t a dry synopsis. It’s funny on its own.

The episode introduces the recurring character Goo, which Faust’s outline calls “an odd bird.” The main laughs come from Goo herself: she’s weird and hyperactive. We understand her by the end of the story, but she’s a force of chaos and destruction until then.

Below, see a long quote from Faust’s comedy section for the episode. Note that, partway through, her writing breaks into Goo’s voice to give us the rhythm and tone of the dialogue, before the lines have even been finalized:

She’s one of those kids who operates on a different wavelength than everyone else, and the things that she does as if they are perfectly normal, seem beyond weird to everyone else. But she is completely unaware of people’s perception of her. What is normal to us, is weird to her. For instance, she can’t understand why Mac named Bloo “Bloo.” He doesn’t look like a “Bloo” to her, so she re-names him Chester. In fact, she’s named Goo because her parents let her name herself and her full name is actually Goo-goo-ga-ga, but you can just call her Goo for short ‘cause it’s easier to say than Goo-goo-ga-ga, but her Mom still calls her that when she’s mad, but her Mom doesn’t really get mad at her all that often ‘cause she doesn’t want her to have low self-esteem and end up with an eating disorder and why did Mac name himself Mac? Did he say Mac a lot when he was a baby ‘cause that seems like a pretty weird thing for a baby to say and don’t you think it’s kinda impressive that Terrence named himself Terrence because if you think about it, Terrence is a pretty complicated syllable combination for an infant, wow, Mac’s brother must be pretty smart, I mean, Goo wasn’t able to pronounce syllables like that even though her parents tell her she’s a savant — that’s another word for genius y’know — and y’know... y’know, y’know, Mac’s brother should be home schooled like Goo and shouldn’t use the public school system because her parents say that the public school system doesn’t have anything to offer incredibly gifted children like Goo, but it’s okay for Mac to go to the public school system, ‘cause the public school system is probably best for a kid like Mac who would probably benefit from the public school system...

And that is the source of the rest of the humor in this episode. Goo drives Mac CRAZY!!!

The comedy section continues like this for a while, laying out the ways that Goo (accidentally) terrorizes Mac. Faust wrapped it, and the whole outline, with a disclaimer. “It sounds awful,” she wrote, “but it’s going to be funny because it’s Mac, and not you.”

That was the show’s humor style in general. McCracken has tweeted that TV cringe comedies from the time — like Curb Your Enthusiasm and the original British version of The Office — inspired the humor in Foster’s. Another point of reference: the retro screwball comedy genre, “where every chaotic thing builds on the next chaotic thing.”

With the outline approved, it was time to write the screenplay. Here’s McCracken on that pipeline:

The writer gets 3 weeks to write a script at which point it’s turned in to Lauren and I to review […] Each script is around 38 to 42 pages and we make notes. We ask questions like: are the emotional beats there? Is the story being told not just through dialog but through the visuals as well? Does the overall pacing feel right, and is it funny? Once the notes are made, either the writer or Lauren and I will implement the changes and send it off to Cartoon Network in Atlanta for approval.

In reply, a reader asked how many revisions each script went through — guessing 10 as a baseline. Today, when a Hollywood series pitch can go through more than 26 rewrites, that might not even sound unreasonable. But McCracken made it clear that the scripts for Foster’s weren’t being torn apart by notes. Again, that small, tight group oversaw the series:

10 revisions!? No, it’s more like 1 or 2, 3 at most. If we had 10 revisions we’d never get anything done, also I think that would drive me crazy. […] Notes come from me, Lauren and a couple of people in Atlanta. That way we can get things done quickly and efficiently, not too many hoops to jump through.

This was possible because, as he put it, the Cartoon Network producers and executives actually cared about the show — and were good at their jobs. “They basically act as our first audience and give us an indication of what is and isn’t working,” he wrote. Most importantly, they didn’t “give the typical executives notes like, ‘Hey, what if the cats were ducks?’ ”

Final revisions were made (including the notes from the Standards and Practices department) and then the team recorded the voices. A typical episode of Foster’s took around four hours to record, with the actors all crammed into the booth together. It was here that the script really came alive for McCracken.

As he put it, “We can write and draw a funny-looking guy saying ‘I like cereal,’ but it’s not until Candi Milo as Cheese says ‘I like cereal’ that it becomes hilarious.”

With recording done, the script was locked down. The creation of a Foster’s episode continued from there — as the storyboarders drew the action based on the voice recordings.3 There’s a boarding guide from the series available online, packed with notes by McCracken on staging and pacing. It probably deserves a write-up of its own.

But that, at least as far as the old blog detailed it, was the writing process.

Writing for animation tends to be overlooked and undervalued. Only some animated projects are affected by the ongoing Writers Strike over unfair Hollywood terms, but that’s not to say animation writers have it better. Like Christopher Miller recently tweeted, writers on animated feature films “have even lower minimums, less healthcare and fewer credit protections than WGA equivalents.”

What’s clear from Foster’s, though, is that a great script can lead to a great animated series. McCracken kept his next shows script-driven — even his zany, ultra-cartoony Wander Over Yonder. As counterintuitive as it may sound, words on a page can create animated classics. It’s an art of its own that deserves respect.

2: Animation news worldwide

The Spider-Verse phenomenon

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is the most talked-about movie of the moment. It’s a blockbuster with a strong human story, and it doubles as an avant-garde visual experiment. An early scene takes place in the Guggenheim, which is only fitting. Today, the Across the Spider-Verse artbook hit #1 across all books on Amazon.

The film’s box-office totals rose this weekend to $225.5 million (domestic) and $390 million (all countries), beating its predecessor’s lifetime numbers. In domestic theaters, Deadline reports that Across the Spider-Verse saw a 54% fall compared to last weekend, but calls this “fantastic for a Marvel movie, after you consider a bulk of the Disney MCU titles have tumbled -60% to -70% in the post-pandemic era.”

Deadline names China the film’s largest market abroad, with $34.1 million at the box office — and glowing reviews. The Chinese poster for Across the Spider-Verse depicts Miles as Sun Wukong standing against the heavens (in this case, the Spider-Society).

Meanwhile, the film is a surprise hit in Russia, where it hasn’t actually been released. Pirate preview screenings on Thursday apparently topped Russia’s charts.

Numbers aside, the coolest discussions around Across the Spider-Verse have been the behind-the-scenes dives from its team. On Twitter and Tumblr, Chelsea Gordon-Ratzlaff explained how the animators resculpted the characters in each shot. Great tweets came from Daniel Ceballos on the use of reference footage, Nick Kondo on the new web technology, Kris Anka on the development of Spider-Man 2099 and Seng Khantrum on how director notes guided shots.

The standout character Spider-Punk, a living collage, got a lot of attention on his own. An Ami Thompson expression sheet for him went viral. Spencer Wan shared the animation test that led to the character’s style, and director Justin K. Thompson replied, “I remember seeing Spencer’s test for the first time. I loved the anarchy of it. The complete redefinement of the rules we used on the first film.”

Animator Li Wen Toh had this to say:

I animated the first 10 seconds of Spider-Punk exploding on screen! For this running shot, I animated Hobie’s body on 3s/2s, his guitar on 4s, and his outline on 2s/1s. The directors and supes liked it so much it sort of became the template for Hobie’s framerate offsets.

Maybe best of all is the story behind the film’s Lego sequence, created by a 14-year-old animator in Toronto. The New York Times did a piece on that, which is a must-read.

Newsbits

We lost animator Lin Wenxiao (89), one of the last living grandmasters of Chinese animation. There’s been an outpouring of tributes from scholars and former colleagues. You can’t summarize her career in brief — we’ll write more soon.

In France, the Annecy festival (the world’s biggest animation event) is underway. Sneak peeks and interviews are already appearing on its YouTube channel.

On that note, check out the teaser for Electro Andes from Argentina — pitching at Annecy’s MIFA event this year.

In Mexico, the press has an update on Guillermo del Toro’s next stop-motion feature with Netflix, The Buried Giant. Producer Melanie Coombs says that it’s still in the “very early” concept stages and could even be four years away.

Also in Mexico, the stop-motion studio El Taller del Chucho (Pinocchio) is working to secure deals for two feature films — one a co-production between Mexico and Spain, the other between Brazil, Mexico and Uruguay.

My Friend Tiger (2021) by Tatiana Kiseleva, from Russia, is now online. It’s a remarkable film, even better than Kiseleva’s earlier A Tin Can.

In America, Chris Nee had devastating things to say about the handling of preschool shows in the streaming era. One highlight: “Where I get worried is, God bless Cocomelon, they figured out something that worked really well for them, but I don’t want to make shows that way.”

Following the premiere of the Chinese feature I Am What I Am in Japan, anime industry figures like Kunihiko Ikuhara (Sailor Moon) and Yasuhiro Irie (Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood) are praising the film. Makoto Shinkai calls it “amazing.”

In September, the annual Cartoon Forum pitch event will take place in France. This year brings 78 shows and specials, including Luce in the Lovely Land. That’s a series based on Luce and the Rock — one of the best short films of 2022.

The English studio Aardman is running its first in-person animation course since before the pandemic.

Lastly, we looked into the meaning of manga eiga, or “cartoon movies.”

Until next time!

Today’s lead story draws from these lost posts on the Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends blog: Making a Show: Step 1, Making a Show: Step 2, Readable Outline, Making a Show: Step 3 and Making a Show: Step 4. We also used the comments written under them by McCracken and Faust. (One source we consulted but didn’t quote was the press kit Q&A.) Some of these links may be broken for email readers — if so, try them on the website.

As ever another excellent piece.

good