Welcome! We’re here with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is our plan today:

1) Katsuhiro Otomo’s Combustible (2012).

2) Animation newsbits.

With that, here we go!

1 – “Something Japanese”

Akira defines Katsuhiro Otomo’s reputation. He started the manga series in 1982 and finished the film version in 1988. Both became hits — and the Akira movie, particularly, has overshadowed the rest of his career. Not one of his anime projects before or since has gotten the same notice.

And yet, for years, Otomo wasn’t in love with that film. He found its process crushing and “not fun,” and he felt that the project’s structure — a barrage of 2,212 short shots — was a mistake. Otomo said that “there were just too many cuts,” which gave the animators “way more work than they could do, so that meant they did a lot of overtime and had to make compromises in terms of animation quality.”1

Otomo warmed to the Akira film eventually, but he’s always been more at home in strange, off-the-cuff projects. He likes to experiment and enjoy himself. That’s how you get oddities like Roujin Z (1991) or Cannon Fodder (1995): Otomo tries something to see where it leads.

This is also the origin story behind his film Combustible (2012). In 2009, Otomo went to the Annecy festival in France and watched shorts from around the world. “I decided I wanted to make one for myself too,” he said. It was a bit of a whim — a producer traveling with him liked the idea. The thinking was, “It’s easy, so why not?”2

Otomo acts nonchalant when he talks about it (in fact, he acts nonchalant about most things). But that spur-of-the-moment decision led him to a beautiful film. In 12 minutes, he presents one of his best and most emotionally intense works.

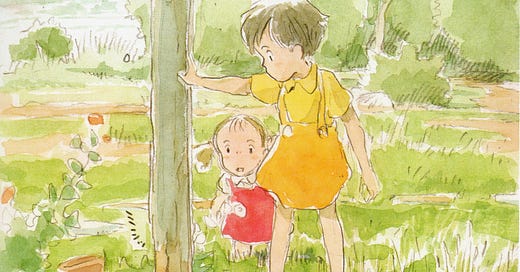

Combustible is about Owaka, a woman in the Edo period who’s arranged to be married. The idea tortures her. She loves a fireman named Matsukichi, her close friend since childhood — but they can’t be together.

Then she accidentally starts a fire inside her family home. In a chilling moment, she decides to let it burn, fully aware that the city around her is a tinderbox of wooden buildings.

The story hinges on that scene, which might be the finest Otomo’s ever put to film. It was Combustible’s standout for him. “When you see the fire, in the eyes of Owaka, is my favorite part,” he said. It’s an extremely subtle, layered thing — the opposite of the Akira movie and its explosion of glitzy effects. Otomo’s style had changed, as had his goals.

With Combustible, his aim from the beginning was to make an Annecy-esque short that would screen at Annecy. His time as a director of big-budget features was over, in part because the backing wasn’t there — his follow-up to Steamboy (2004), Steamgirl, never happened. So, here, he looked to the festival circuit.

That guided the project. Otomo was told “something Japanese” had a better shot at festivals abroad — which led him to the Edo era, a setting he’d dreamed of using in a film. He needed a small story to keep the runtime down, so he picked his own manga short Night Flames (1994). And he needed money and a team from the industry, so a wider anthology, Short Peace (2013), was dreamed up as a vehicle for Combustible.3

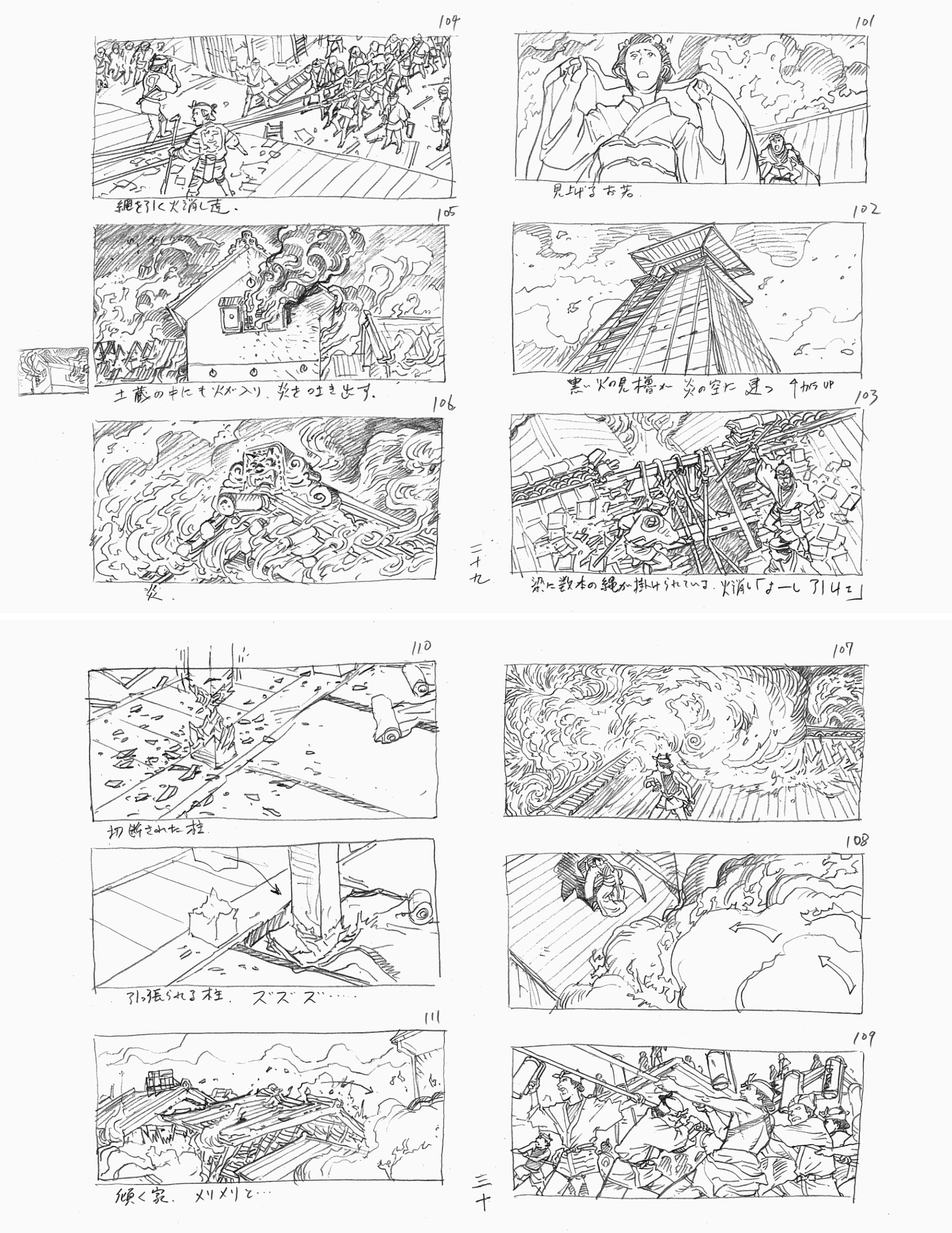

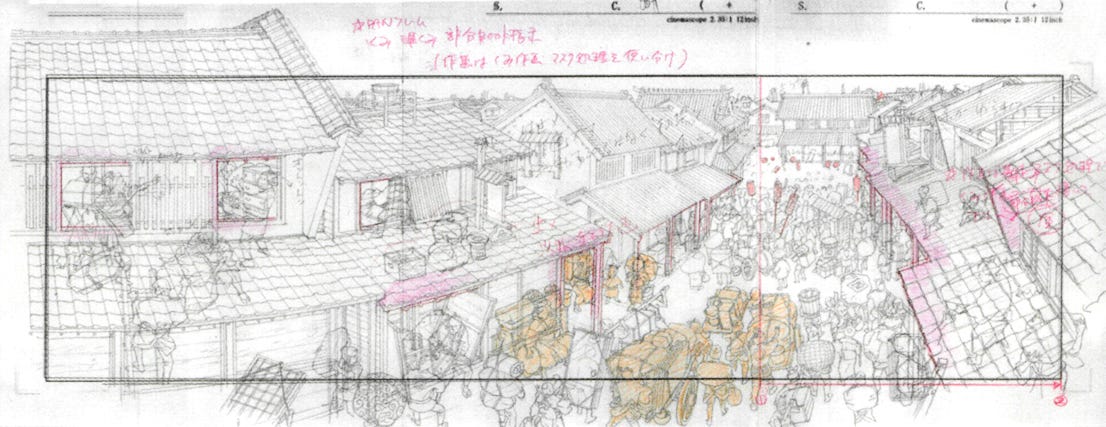

Otomo has called the resulting short an experiment, and it was — in its look, its story and its project structure. He went in without a script and storyboarded without the industry-standard templates. “I wanted it to look like an illustrated scroll (emakimono), so ... I drew the storyboard on pieces of B4 copy paper laid horizontally,” he said.4

At the core of this film is research. The team tried to capture something essential about old Japan — even looking for actors familiar with the Edo dialect. Discoveries made it into the film: Otomo learned while studying that people rarely ran in the Edo era and, when it did happen, their arms didn’t move much.5

The list continues. A lot of Combustible is shot in “parallel perspective,” in line with traditional scroll art. Otomo drifted from his original manga and took from stories used in the traditional performing arts, like The Fire-Loving Son (from rakugo) and the tale of arsonist Yaoya Oshichi (common in joruri). One of the biggest reference points was the Ban Dainagon Emaki, a scroll from the 1100s that deals with a massive fire.6

Although Otomo went all-in on accuracy at first, he found old Japan too complex to recreate perfectly. Too many things varied across time, and so he had to find a balance. As he explained:

I really struggled trying to make Edo look realistic in animation. I collected various materials and visited museums, but the more I researched the more things just kept coming up. It’s not up to historian standards, but by being too accurate with the portrayal it begins to look a little too strange and unfamiliar to regular people, so rather than a realistic approach, I mainly focused on trying to achieve an aesthetic close to the style of Japanese picture scrolls. As for creating the fire scene, there’s a scroll from the 12th century that depicts a fire outbreak, so I showed it to the staff, the way the smoke was depicted and the shape of the flames, and I said to them, “Let’s make this move.”

Otomo’s whole approach came from a late-born fascination with Japan’s past, seen also in the original Night Flames. During his early career in the ‘70s, he was obsessed with new-school foreign directors like Sam Peckinpah — and foreign comic artists like Moebius. “As I get older,” Otomo said, “I find old Japanese literature and things like that interesting.”

Combustible was meant to be a hybrid of past and present, though. “I wanted to take that old theme that we used to have in Japan 300 years ago, and describe [it] with recent technologies,” Otomo noted. It isn’t a throwback: it’s a story that could only be told with computers.

Otomo’s always been a champion of digital animation. “We’re being liberated from the animation technology of the past,” he argued in the mid-1990s. His prediction then was that CGI would lead to a whole new kind of filmmaking. Combustible’s often seamless blend of CG and 2D animation proved him right.

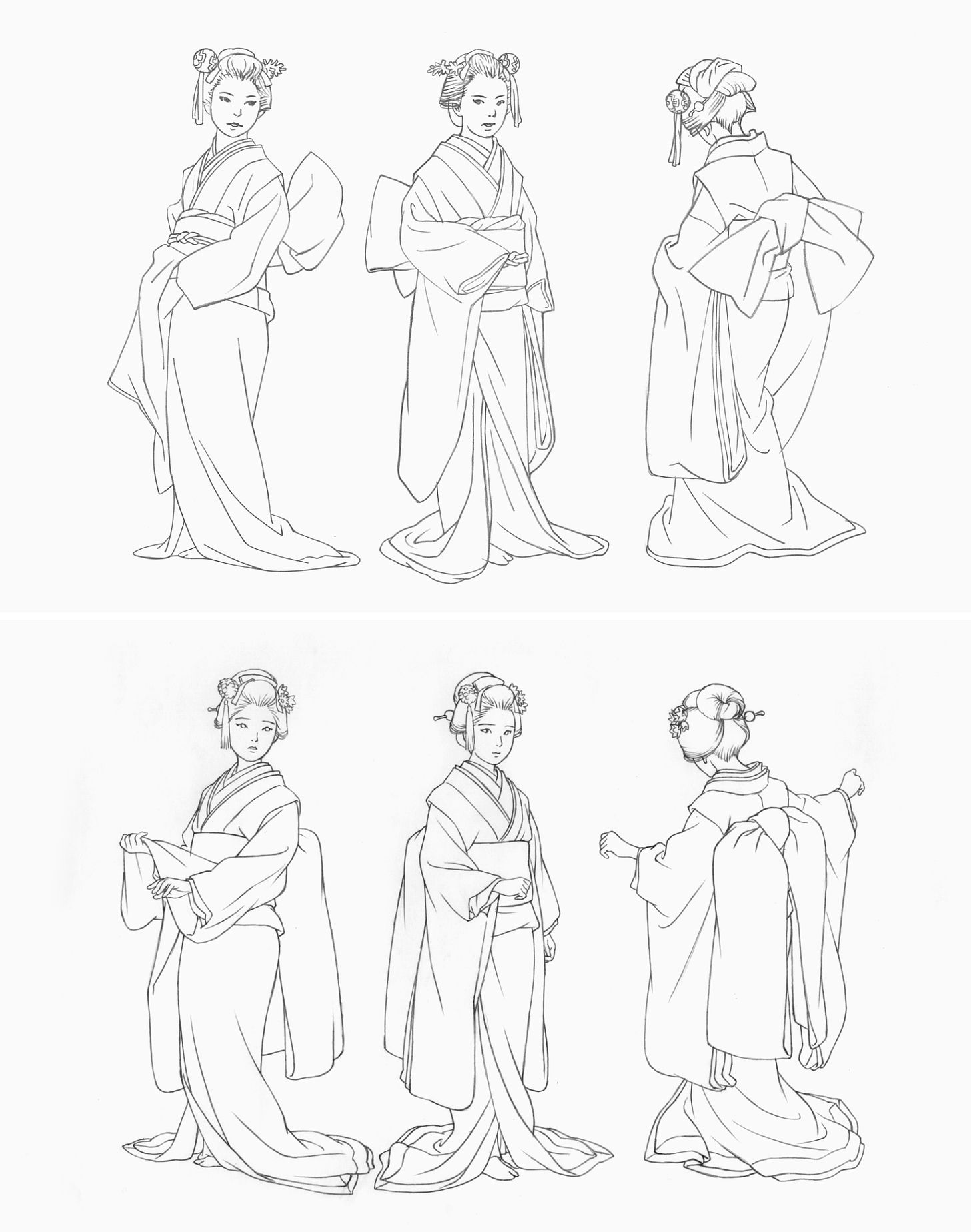

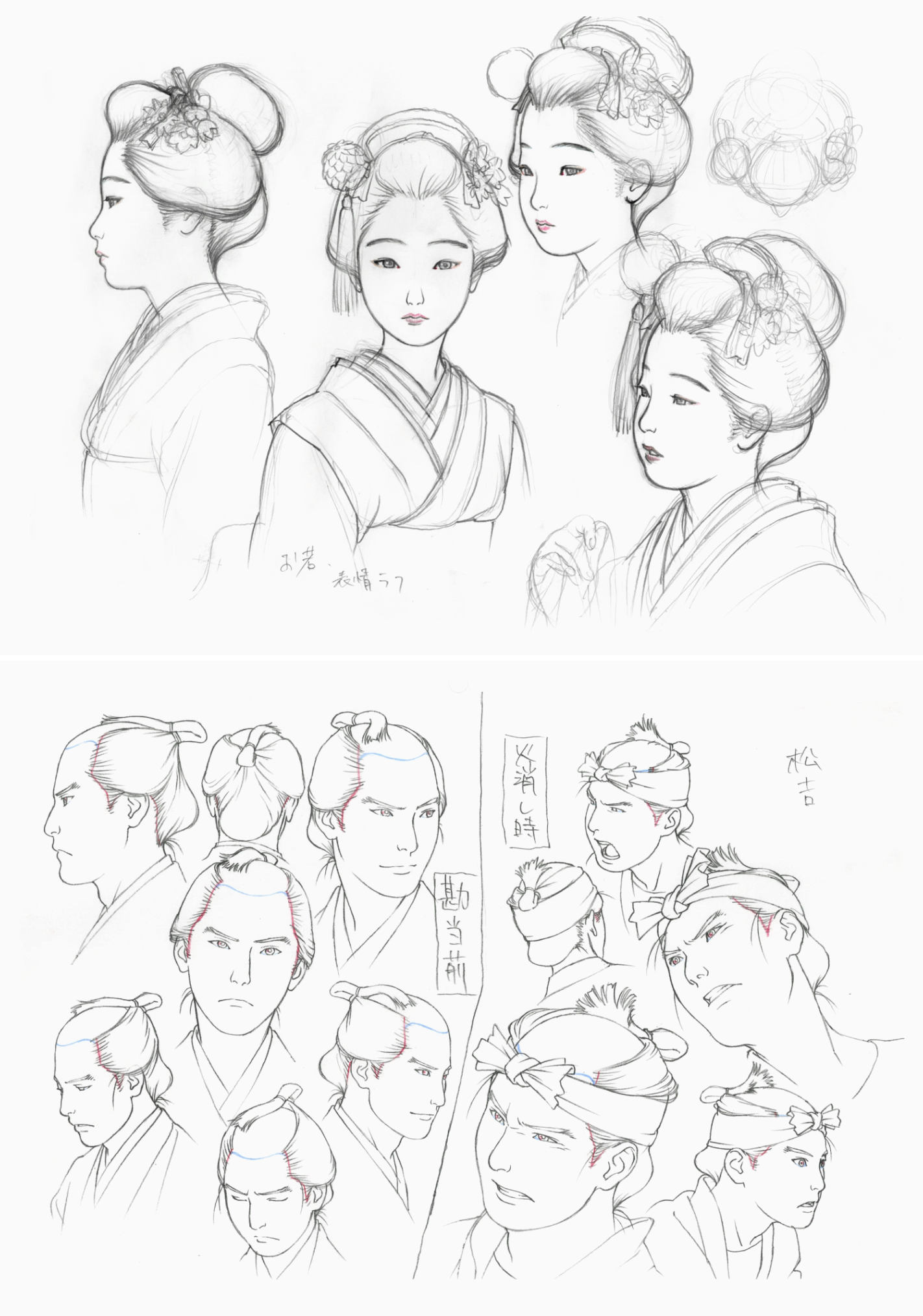

The film is a feat of digital lighting and compositing. And many of its key visuals, like the kimono patterns and complex hairstyles, relied on computers. These staples of the Edo era were “taboo in anime,” Otomo said, because of the difficulty involved in drawing them. Even with his team’s digital tools, it wasn’t easy:

For the designs on the kimonos and the tattoos, we created the texture with a brush and drew each frame by hand. It took a lot of time but the composition is limited, so it was within our capabilities. Certain parts of the characters were also done in 3D CGI as were the Japanese hairstyles, with CGI placed on top of the heads of drawings like wigs. Ultimately, the reason why depicting Edo in anime form was so difficult was all the detail. The kimonos were hard to get right — creating the silhouettes alone was difficult enough.

Combustible took around a year, with a fairly big team. On staff were many Otomo regulars, including character designer Hidekazu Ohara (Cannon Fodder), CG director Shuji Shinoda (Steamboy) and animator Masaaki Endo (Akira). Otomo did more than his share, too. “I took charge of almost the entire layout and background designs myself — right down to the roof tiles,” he noted.

As with Akira, he wasn’t totally satisfied with the end result. It was a little short, he felt. He asked the producers if he could add “five more minutes” — and the answer was no.7

Still, Otomo did get his Annecy screening. Combustible competed in France for a Cristal grand prize in 2012. It also made the Oscar shortlist in America and, in Japan, won the hyper-prestigious Ofuji Noburo Award (given in other years to Millennium Actress, A Country Doctor and The Boy and the Heron). He’d pulled off his festival film.

Not unlike the Short Peace anthology that houses it, Combustible is very compelling, very unique and fairly obscure. Many haven’t seen it and most streaming services don’t carry it. Otomo’s reputation is still, first and foremost, just Akira. But this short, like Cannon Fodder, shows again that Otomo-the-director is much more than one movie from the ‘80s. Even if he doesn’t get credit for his range, the work speaks for itself.

2 – Newsbits

In Croatia, Zagreb Film continues to upload intriguing animated shorts to YouTube. Two recent additions: 1x1=1 (1964) and AbraKadabra (1957).

Anime is now making less money in Japan than it makes abroad: $10.6 billion to $11.2 billion. Animenomics explains what these numbers mean.

Animator Zhang Xu Zhan of Taiwan did an English-language interview about his Compound Eyes of Tropical, a stop-motion film that’s been catching our attention. See a trailer here.

In Cuba, historian Abel Molina Macías is fighting to preserve the fading history of ICRT, whose animated projects for Cuban television have gone mostly undocumented.

The studio NOMINT, in England, has shot a stop-motion film with a thermal camera — using a heat gun on 3D printed characters to make them glow. It’s set to Radiohead and is absolutely worth a watch.

Cartoon Brew explored the history of the wild take, one of the hallmarks of American animation (although not totally exclusive to the States).

Feinaki Beijing Animation Week is happening in China right now — it’s an important event each year. On Bilibili, the festival has created a playlist of more than 60 trailers for the work showing at the 2024 edition.

The Nigerian film Hadu won in the animated short category at the African International Film Festival, while Leon and the Professor (also Nigerian) picked up a special mention. You can watch Hadu’s trailer here.

In Italy, Yoshitaka Amano (Vampire Hunter D) is holding a career retrospective exhibition in Milan. Its title: “Amano Corpus Animae.”

Lastly, we went behind the scenes of Revoltoso (2016) — animated cubism from Mexico.

Until next time!

Otomo discussed his problems with Akira in the book Akira Animation Archives and an interview with Forbes. The “not fun” language comes from a Techinsight article.

The 2009 date comes from here. Otomo’s line about making a short of his own appeared in an interview with asianbeat, now archived (it’s the source for many of our quotes today). The other quote is Nikkan Sports. More information about the Annecy trip is in Otomo’s interview for the Short Peace website and this Natalie article, both used throughout.

See Otomo’s interview with Gigazine, plus an article in Animation Magazine. Both were important today.

From an interview in Akiba Souken. The point about experimentation was made in a Cinema Today article.

The voice casting was discussed in this interview with HMV, while the point about running in Edo comes from Akiba Souken.

For details on the reference points used in the film, see the producer’s production notes.

Always glad to see appreciation for the works in Short Peace. 'Combustible' is an exceptional short, and it's really cool to see these production materials. The settei are so clean - as expected of Otomo's circle! but given how tiny these characters appear in the short, it's amazing seeing the details up close.

I actually purchased Short Peace after coming across Possessions on YouTube and wanted to own it in high res. Love this anthology, wish they could do more shorts like these!! Thank you for this awesome backstory- rewatched the short again after reading this!