Welcome back! It’s time for another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing:

1️⃣ Breaking down the “one-shot” animation of Cannon Fodder.

2️⃣ The world’s animation news.

For anyone just finding us — it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. Get them free in your inbox, every week:

Now, let’s get going!

1: Like a scroll

Today, computer animation is the standard. That’s true for big 3D films like Across the Spider-Verse and for the bulk of everything else. Even 2D projects tend to be computer-driven — from the mainstream (Primal) to the indie (Lackadaisy).

It’s opened up the medium. Anyone with a computer can download Blender and create shots that, 40 years ago, a whole team of professionals couldn’t have animated. Beginners have unlimited layers. They can undo mistakes. Maybe most of all, they don’t need to record their work on physical film with physical cameras.

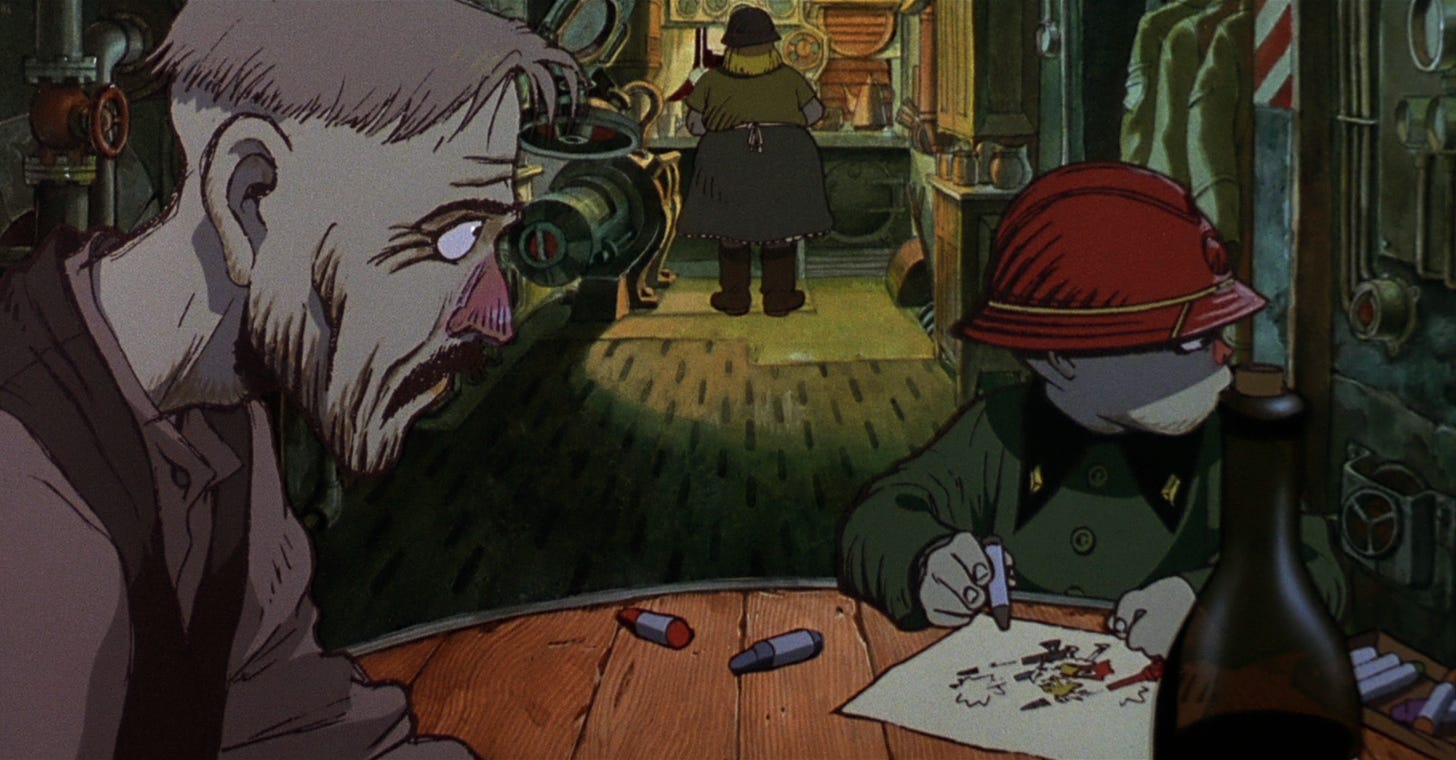

When Katsuhiro Otomo directed Cannon Fodder (1995), though, things were different. Most Japanese animation still began with pencil drawings on paper. These were transferred to cels via “tracing machines” (think Xerox but neater), then painted and photographed. If a sequence was too complex to photograph, it wasn’t usable.

But Otomo wasn’t dissuaded. With Cannon Fodder, he chose to shoot the unshootable. It’s a 2D film that looks like it was recorded in one long take. His earlier Akira (1988) had been a barrage of quick cuts — its average shot length was purposely brief. “So I guess I tried to make it longer this time,” he said.1

The idea came to him as he storyboarded Cannon Fodder. “While making the first scene into a panning shot,” Otomo explained, “I had this vague thought about seeing how long I could continue that. So, I decided to go as long as I could.”2

The excerpted scene below shows how it turned out. The camera travels seamlessly through the world, in every direction. It feels effortless, but it wasn’t. “Of course, thinking it up was easy,” Otomo said, “but making it a reality was insanely difficult.”

When Studio 4°C first started Cannon Fodder in the early ‘90s, the company was low-tech. “No matter where you looked, there was no such thing as a personal computer at Studio 4°C. There were a few word processors, though,” recalled one worker there.

The worker in question was Sunao Katabuchi, who’d been the assistant director of Kiki’s Delivery Service a few years before. He would be crucial to solving Cannon Fodder.

Around 1993, Katabuchi happened to visit the main branch of Studio 4°C in Tokyo. Otomo was planning Cannon Fodder there at the time, this dystopian satire about a city that revolves around cannons — shades of Imperial Japan. Out of the blue, the head of the company asked Katabuchi if he owned any material about cannons for Otomo to study. He did, by coincidence.3 From that point, he was in.

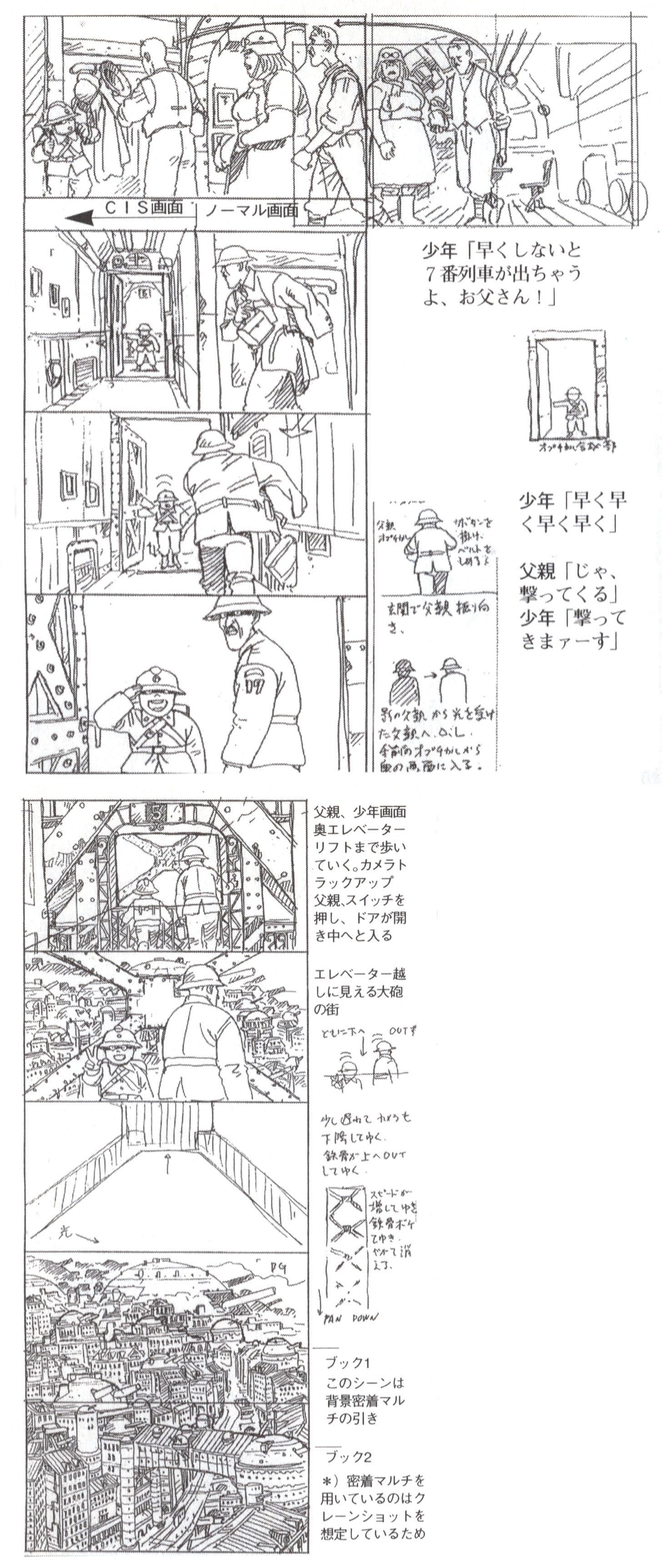

Katabuchi got to see Otomo’s hyper-detailed Cannon Fodder storyboard that was giving the team trouble. It was designed in an unbroken flow — “like a scroll,” Otomo said — and some panels directed the camera to follow characters down hallways.

He was defying the rules of what could be photographed in 2D. Before Katabuchi got involved, tests had even been done with a physical set, modeled in three dimensions. But Katabuchi had experience with special effects thanks to a Little Nemo pilot film: optical compositing (the precursor to digital compositing) and 3D graphics. He decided to see if Cannon Fodder could be done.

It helped that Otomo wasn’t stuck on the idea of a purely one-shot project. For him, it was more about a feeling. Edits were fine as long as they were mostly disguised. Cannon Fodder came out looking continuous, but Katabuchi ultimately broke it down into 30 or 40 “blocks” that could be filmed separately.

“We had to make each block something the photography stand could handle,” Katabuchi explained, “and make the seams easy to identify so that we could bring it all together into a single shot later, which made it a difficult puzzle to assemble.”

From the storyboard stage, Otomo’s camera directions were intricate. Yet they were never enough on their own.

Early on, test footage was made out of his storyboards to check the timing of the camera, which turned out to be too fast. (“You need to take it slowly in slow spots and have variation; otherwise, it’s painful to watch,” Otomo realized.) The storyboards were also blown up, cut up and assembled to determine the scale and placement of everything. This prep made way for the layout stage, where the camera angles and movements were refined even further.4

When it came time for the final artwork, the demands of Otomo’s flowing camera were steep. The background paintings were endlessly long, and stuck together in unorthodox ways. The animation cels were in a similar state of chaos. As director of photography Hiroaki Edamitsu recalled, “When the materials arrived, I lined up the BGs on the floor to see how they would be connected, but they didn’t fit in the room.”

Katabuchi is the one who mapped out the shoot — Cannon Fodder’s animation director said that the film “would not have been possible” without him. Based on Katabuchi’s lengthy instructions, Edamitsu manually marked down X-, Y- and Z-axis coordinates and filmed accordingly. Even then, problems arose that had to be fixed on the fly.

“The content was just so dense,” Edamitsu said, “you didn’t know how it would look until you actually put the cels down there.”

Edamitsu’s camera stand was limited in its size and range of motion. To create the illusion of an unbroken flow, he had to set up, adjust and tear down the artwork on the stand again and again. Shooting was analog (he didn’t have a computerized camera), and every tweak carried the risk of jitter, scratches and continuity errors.5

The very worst scenes took Edamitsu three 15-hour days in a row to shoot, and 90 minutes to record a single second of footage. (Cannon Fodder is over 20 minutes long.) Retakes in this situation were all but impossible. As Cannon Fodder’s animation director said, “The entire thing was basically all-or-nothing.”

Whenever one of the long “blocks” was being filmed, the lights in the room couldn’t be turned off. As Katabuchi noted, their brightness was always slightly different when they came back on — ruining the continuity of the shot. So, they needed to be left on for days at a time, which brought about another small crisis. Katabuchi again:

… the backgrounds that were drawn on thin paper were left exposed to light, causing them to dry and shrink in size. As a result, the shooting scale that had taken so much effort to record became more and more out of sync.

Asked about his solution, Edamitsu replied that he’d just have to follow his gut.

Although Cannon Fodder was primarily analog, around four of Katabuchi’s “blocks” couldn’t be done without computer graphics — especially the hallway shots. Before production started, Studio 4°C acquired a Macintosh Quadra that could render simple 3D if given enough time. Katabuchi decided to try it. As Otomo said:

We drew a 3DCG hallway and then slapped on a background texture, but back then, computers were insanely slow and it took about a week to do the processing. If we had a retake, that’d be another week.

To create these effects, Katabuchi and CG artist Hiroaki Ando scanned cels and backgrounds into their computer and combined them with 3D assets. The results were usually printed back onto physical film and spliced with the traditionally shot sections. Other times, Katabuchi printed the results on paper, cut them out with scissors and pasted them onto cels by hand. After that, they were photographed.

The trouble, again, was continuity. Every single step of this process changed the colors from the ones they intended: shooting, scanning and printing. By the time the CG shots were ready to use, Katabuchi wrote, the colors were “completely different.”

It took time to get around this problem: test after test, monitor calibration, a special lightbox to study their film output. Katabuchi said that he and Ando had to “completely cover the monitor with a blackout curtain,” sticking their heads under it to avoid glare — a big concern with monitors in those days.

Even so, it came down to eyeballing in the end. “With the adjustments themselves,” Katabuchi wrote, “it’s not like something computed and generated them; we decided them by hand, based on what we saw with our own eyes and our own color sense.”

In some ways, what they achieved was the culmination of traditional animation photography — just as it was being replaced by a more streamlined system. Cannon Fodder itself was part of that replacement: the stuff that Otomo and his team learned here would be expanded into the digital workflow of Steamboy (2004).

But Cannon Fodder, at heart, was never truly computer animation. Even the digital parts were weirdly analog. Looking back on the film in 2011, Katabuchi wrote:

Colored pencils. Scissors and double-sided tape.

Cels and cel paints. Plywood.

A loupe to look at the film on a lightbox.

A digital color copier on a personal computer.

A blackout curtain that covers the head when looking at the monitor.

Human hands and eyes and taste.

And perseverance.These are the types of things that created Cannon Fodder.

If you haven’t seen Cannon Fodder before, it’s the last film in the Memories anthology, streaming for free on Tubi and other services. Its camerawork feels like an achievement even now — it’s well worth a look.

2: Newsbits

A good friend of the newsletter, the animation researcher who writes as Toadette, has published a final, going-away article for the centennial of Czech animator Břetislav Pojar. It includes a Pojar interview never before seen in English.

Cartoon Brew has an interview with Oscar hopeful Tal Kantor (Israel) about her powerful film Letter to a Pig, which captured our attention last year.

At long last, the Mexican stop-motion series Frankelda’s Book of Spooks will hit Max stateside on October 12.

Meanwhile, Radix has new details on the feature film Insectario by director Sofía Carrillo — one of the so-called “Magnificent Seven” of Mexican stop-motion.

American researcher Esther Bley is running a database called Queer Animation, paired with their new Cartoon Research column The Cartoon Closet. Historian Jerry Beck has already endorsed Bley’s work — definitely one to watch.

China’s military has released a piece of anime-style propaganda animation about “reunification” with Taiwan. The cutesy, commercial visuals and voices make for a disquieting watch.

In Turkey, the domestic animated film Minderler Adası: Kılıcın Sahibi hits theaters October 13. Trailer here.

Better news from China: Bilibili has revealed the winners of the 2023 Little Universe awards, aimed at rising animators. You can watch them via Bilibili — one standout (with English subtitles) is the charming Mushroom by Han Li.

In Japan, Hayao Miyazaki is hard at work on a new movie. Toshio Suzuki reports that Miyazaki asked him, “By the way, what was my last film about? I can’t remember.” He’s fully on to the next thing. “He started talking about a new project, so I’m not stopping him,” Suzuki says. “As long as he’s working, I won’t be able to retire. He’s 82, and I think he’ll go on until he’s 90. I’m going with him.”

Gen Z anime fans are a rising force in Indonesia. That trend, Animenomics explains, is global. New research suggests that almost “half of Americans aged 18–24 watch popular anime.”

Lastly, we covered the art of collage animation — in the words of several excellent collage animators from across time.

See you again soon!

From the book The Memory of Memories, cited throughout.

From the liner notes on the Memories Blu-ray from Discotek Media. We also cite these, and the written interview with Otomo in the special features, throughout the piece.

From Anime Style’s interview with Cannon Fodder animation director Hidekazu Ohara, cited several times. He was a veteran of Topcraft who’d animated on The Last Unicorn and Nausicaä.

Studio Ghibli did have a computerized camera setup at the time, though — a handful of tricky shots in Cannon Fodder were filmed there out of necessity.

As expected, another fantastic article. Thank you for the wonderful mention about my database and column on Cartoon Research.

Neat! I think it's time for a rewatch.