A Film That Lives Forever

The Oscar nominee 'Windy Day,' plus animation news.

Happy Sunday! We’re here with more from the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is our lineup:

1) On Windy Day (1968) by Faith and John Hubley.

2) Animation news.

Before we start, we’d like to thank everyone for the kind response to last week’s article on Ghost in the Shell. Welcome to our new readers! We saw a lot of wonderful comments, including one from historian Helen McCarthy. And, over in his newsletter, author Matt Alt used our piece as a jumping-off point for his own recollections of working in that era. It’s very cool to see — we appreciate the shout-outs.

With that, here we go!

1 – Windy Day, an immortal cartoon

A couple of years ago, the comic strip Doonesbury did something unexpected. Author Garry Trudeau dedicated a whole Sunday edition to hyping up, and linking, an animated film. “This Oscar-nominated gem has been delighting kids of all ages for years,” he wrote.

The film was Windy Day (1968) by Faith and John Hubley.

We’ve written a lot about the Hubleys. From their first collaboration in the mid-1950s, this husband-and-wife indie team broke rules — and ground. No one else in America made cartoons like them. Their dreamlike Moonbird (1959), built from improvised dialogue and double exposures and modern painting, was the first indie film to win an Oscar in the animation category. Over the next decade, the Hubleys would win two more.

Their work is gorgeous, funny and meditative. It should have held up, but it had a problem. With no major studio push to restore and re-release the Hubley films, many of the old prints simply faded, even as the Disney and Warner classics were reborn for a new era. By the ‘90s, it was hard to recognize a lot of the Hubleys’ animation.

Windy Day endured it better than some, but the general public couldn’t see its full beauty. At least until March 2022, when the Criterion Channel started to stream a restored copy. It’s one of several Hubley films to get this treatment.

Seeing Windy Day in great quality is a revelation. The aging effect that the old prints had on it — that’s gone. All that remains is a timeless, immortal cartoon.

Windy Day is about two young sisters, Emily and Georgia, playing make-believe. Across nine minutes, they walk around outside, bantering and inventing. The story morphs as the girls move between fantasy, everyday conversation, memory and dreams. They “talk with the fascinating logic and abstract thought typical of children,” to quote one historian.1

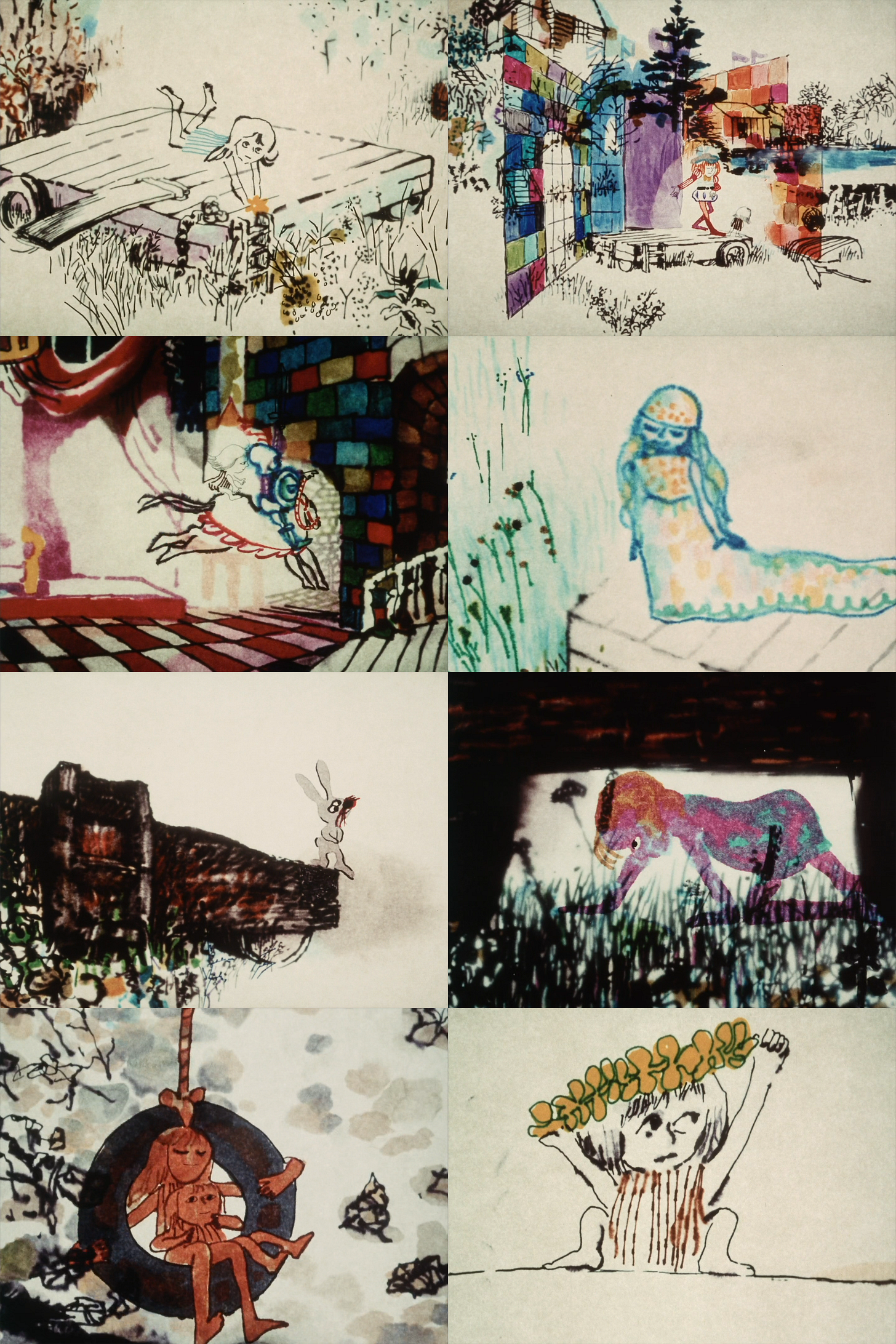

The film visualizes the girls’ make-believe: Emily, Georgia and the world around them all transform in time to what’s said. The sisters become knights and babies, rabbits and dragons. Windy Day is one of the Hubleys’ freest-looking pieces: it’s lovely, loose painting and linework that never stays still. The narrative keeps everything in flux.

Like Newsweek put it in 1969, Windy Day “is what it is — strong, funny, preposterous and then appallingly beautiful — because the children’s imaginations animated the animators’ pencils from the start.” Emily and Georgia are the real-world daughters of Faith and John Hubley. Windy Day is based on a recording of the sisters at play.

The Hubleys had considered doing a cartoon like this for a few years. They’d already made one with a tape of their sons Mark and Ray — namely, Moonbird. As Faith Hubley said:

... in real life our boys are older and the early films related to them more than to the girls. The girls would say, “You like the boys better!” So we talked about it for a long time. John and I had been wanting to do such a film, precisely because it’s very hard for girls to find heroines, characters to identify with.

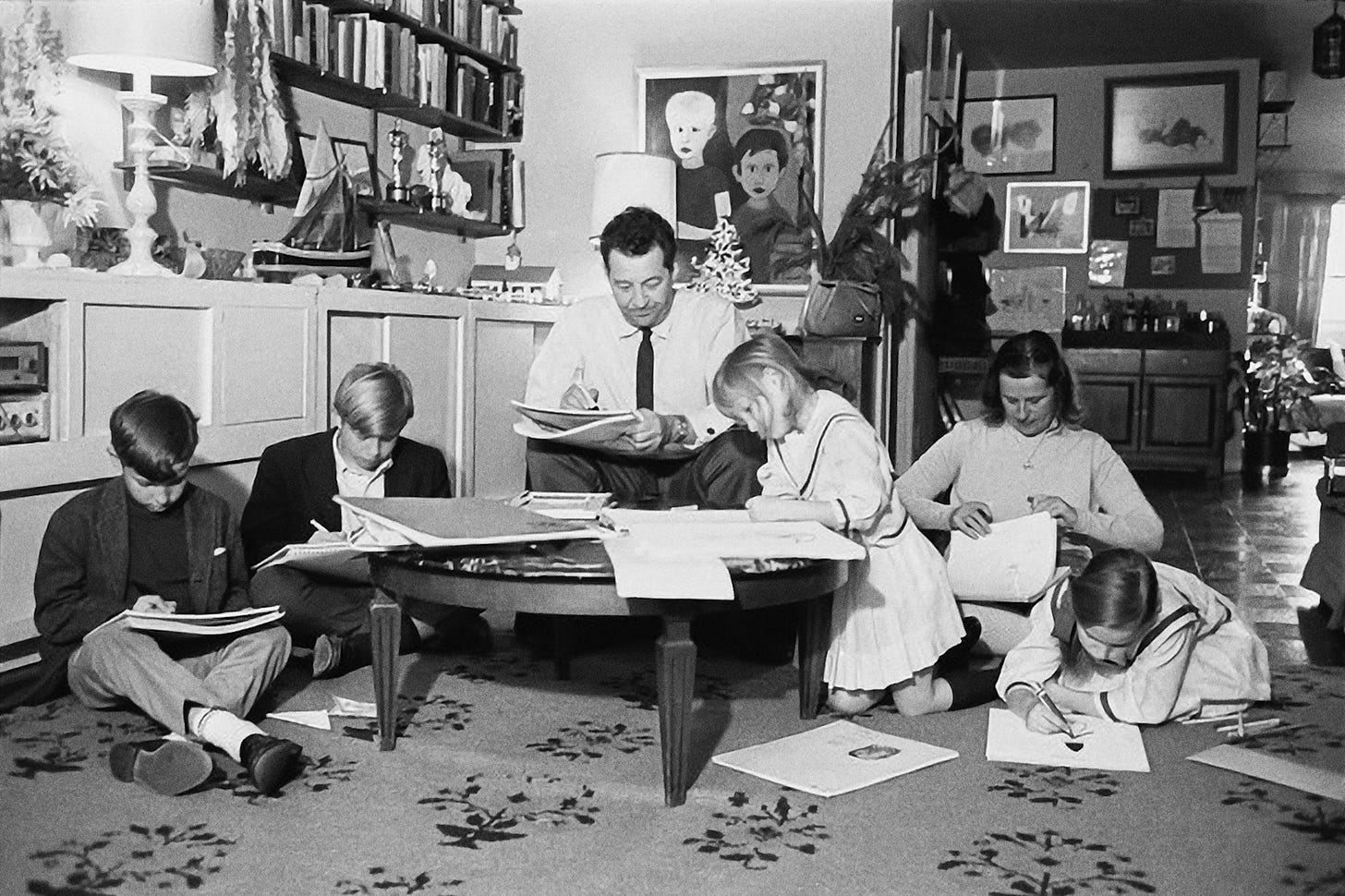

Finally, John and Faith took their daughters to a recording studio. Georgia, born in 1960, was six when these tapes were made. Emily was eight.2 Their parents gave them a basic structure to work with. “We used to just have fun making up these plays on weekends and doing them for people,” Emily remembered as an adult. “They wanted us to reenact that.”

The family recorded maybe two or three hours of audio, almost entirely improvised.3 “When it’d bog down a little bit, Faith would step in and ask a question. ‘Do you think you’ll ever get married?’ And that would start a whole series of [events],” John said.

Out of these recordings, John and Faith got an art film. The attraction for the sisters was a bit more straightforward. “They bought us milkshakes,” Emily Hubley recalled, “and they never gave us milkshakes.”

Hubley cartoons were co-creations. John usually got the director credit, although Windy Day was an exception: it attributes direction and visuals to John “in collaboration with Faith Hubley.” This didn’t reflect a real change in process.

“Faith’s credit on Windy Day, associate director, applies to almost all the films,” John admitted in the ‘70s. “The fairest credit is just ‘a film by John and Faith Hubley,’ without worrying about the details.”

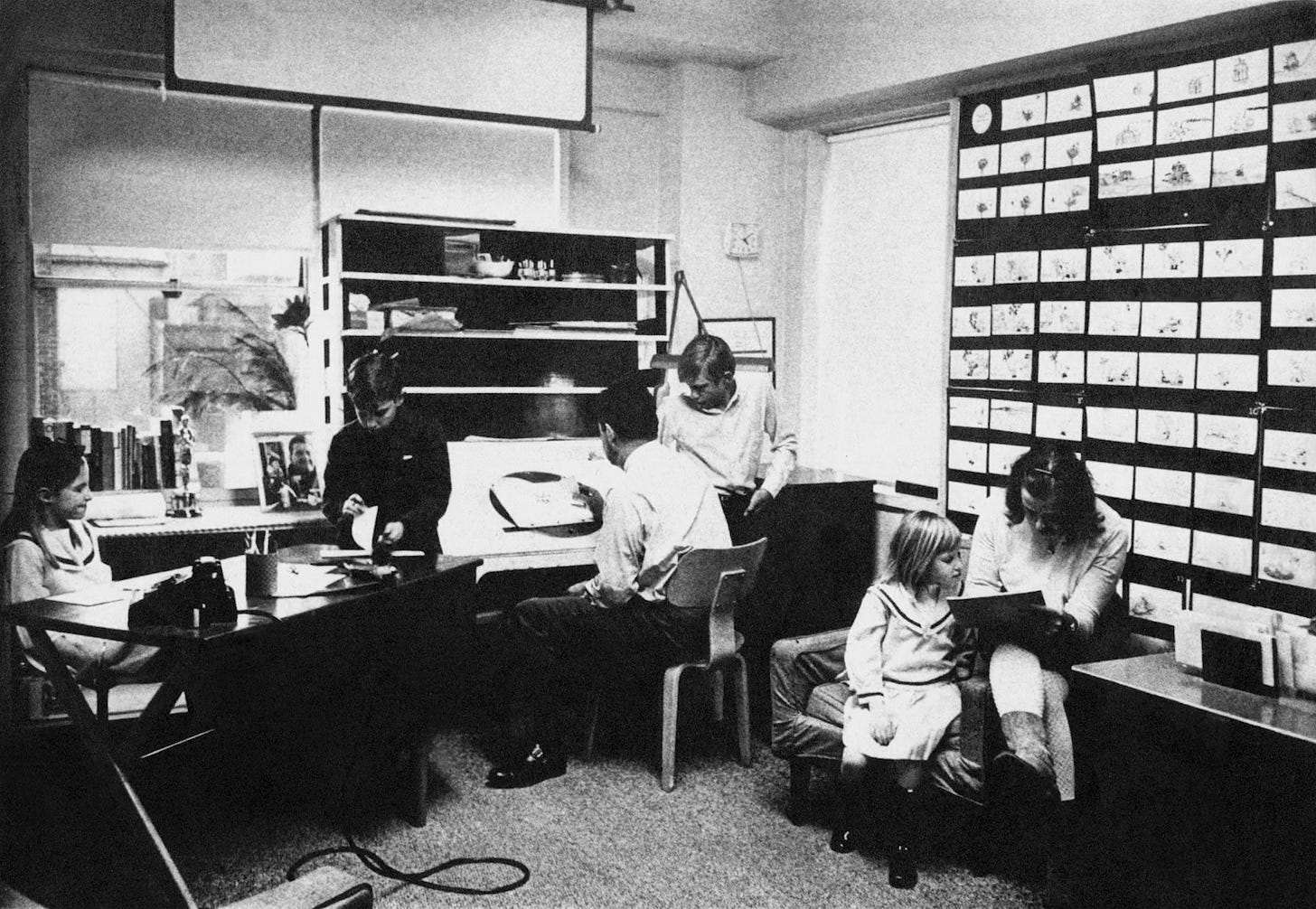

The Hubleys co-edited the girls’ audio recording, cutting hours of material into minutes. They co-authored the storyboard, too.4 Coupled with the designs and layouts, these were the bones of Windy Day, all done by the Hubleys. They kept their teams as small as possible — to keep the films personal.

Another bonus of small teams was flexibility to experiment. As Faith said about their work:

… since John didn’t have to deal with the studio, he didn’t have to use conventional ways, so we could do anything we wanted to do. Anything! We explored reticulation and paper as a medium […] I am a bit of a slob and I like a free-flowing line and texture. That was our contribution — aside from content and the amazing changes in sound, using children, using jazz and wonderful composers, using improvisation — to liberate animation from itself, and to go to watercolors and to paint pastels.

Animator Michael Sporn, who worked for the Hubleys in the 1970s, saw Windy Day as a “new direction” for the team after the Moonbird era. It’s clear and bright — the opposite of Moonbird’s dark, saturated palette. John Hubley called it a “spacious look.”5

The main technique here was backlighting. Shots in Windy Day were drawn across several layers of architect’s vellum, then lit from below during filming. If you’ve ever used a lightbox, the principle is the same: the light beneath shines through multiple pieces of paper, revealing the images on all of them at once. Here’s Sporn:

This probably limited them to three levels including the background. John Hubley built his backgrounds around the animation of the characters, so that they’d be in the clear. However, there are many points where the animation crosses over and is blotted out by the background, but that is accepted as part of the design.

The Hubleys played around, at times using different colors of light to emphasize parts of a shot. Certain effects came from “top light and mattes or double exposures,” Sporn noted. Whatever was necessary to get the look they wanted.

The actual movement in Windy Day is credited to just one animator: Barrie Nelson. He’d worked on the Hubleys’ Oscar-winning Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass Double Feature (1966).

Nelson was a Canadian who’d come to America in the ‘60s — “just before the bottom dropped out of the animated film market,” he said. Nevertheless, he found work with the Hubleys, and the Herb Alpert film was a massive learning experience.6 Nelson gradually gained a reputation. The 1987 book Masters of Animation named him “one of the most talented animators to emerge from the crowded field of Hollywood animation during recent decades.”

Windy Day is among Nelson’s career high points. His animation is rich with free expressiveness, bounce, fluid transformations, evocative faces. He matches the rambunctious energy of Georgia and Emily. This is the kind of motion that rewards a dozen rewatches — or more.

“Barrie Nelson’s animation [in Windy Day] is probably some of the best he’s ever done,” Sporn wrote in 2009. “And I say this as a fan, liking everything he’s ever done.”

With the animation drawn, it came time to render Windy Day. Faith said that she personally “inked every drawing and sent out for the coloring, because the line was so important.” Color was added with things like markers and watercolors — much of that work went to the artists Sara Calogero and Nina Di Gangi.

The children were involved in the art, too. During the scene in which Georgia describes a nightmare she once had, she contributed her own drawings. Emily Hubley later remembered this moment as her own favorite in the film.

This wasn’t too unusual — Hubley productions were family affairs. Emily, Mark, Ray and Georgia assisted here and there, with corrections from the adults. In 1966, as Windy Day was first coming together, Faith told a Canadian newspaper, “They’re not at all self-conscious about making films with us. It’s as if we owned a grocery store. They would not be embarrassed to sell groceries.”7

Even if you don’t have access to the Criterion Channel, Windy Day is so wonderful that lower-res copies (like the one above) still have a power to them. So much power, in fact, that Georgia and Emily Hubley have said that they can’t bear watching the film at all.

Ultimately, self-consciousness ended up hitting in one go. Here’s what Georgia told The Dissolve about her first experience of watching Windy Day:

I can recall transitioning from being a 6-year-old free-spirited chatterbox one minute, and discovering what stifling embarrassment felt like the next. For all of us — I was so mortified that I thought the entire family was humiliating itself… It is beautiful, though.

Emily has agreed. “All the reasons that we can’t watch it, are all the reasons that it’s good,” she once said. “Because it’s so realistic, that it does enter that children’s world and it does reveal a lot about us.”

It was a very public revelation. Hubley cartoons often had poor distribution, but Windy Day was luckier: Paramount ran it before The Odd Couple across more than 100 theater screens in New York and New Jersey alone.8 The studio gave the Hubleys a hand with the budget as well: Windy Day was primarily self-funded, but it had “a little bit of help from Paramount,” as Faith phrased it.

For a family that put art before money and was badly in debt (“I found out later we were totally broke,” Emily said9), these victories counted for a lot. Windy Day got seen, it got an Oscar nomination and the Hubleys continued to push on. They made a film per year, after all — there was no time to slow down.

Windy Day had lots to teach in 1968, and that hasn’t changed. Like the Doonesbury strip pointed out, it’s a film that can and should be discovered by each new generation. Thankfully, the Criterion edition makes making that discovery easier than ever.

We’re fortunate that we can watch the film today as it was meant to be seen. Emily Hubley, an animator herself, became a keeper of the Hubley Studio legacy. It’s thanks especially to her that her parents’ work has made it this far, despite the lack of funding and interest from big studios.

Many times, what gets remembered is just what ends up in front of people — which, over the years, has given studio cartoons an advantage over the Hubleys’ films. But work like Windy Day is every bit as good as the best of Disney, MGM, Warner and the other old majors. All the film needs to prove it is a few minutes of your time.10

2 – Newsbits

The American series Scavengers Reign, which we covered last year, has been canceled by Max. But there’s good news: Netflix will stream the first season, with the option to greenlight a second.

The very moving Russian film The Encounter, about a woman’s return to her childhood home, is now available on YouTube.

A film created in the early years of Japanese animation, Dental Health (c. 1923), has been discovered and preserved.

In Bangladesh, Studio Padma is trying to make an animated feature. Until now, its main work has been local ads (watch) and Japanese anime. It was co-founded in 2014 by Shunsuke Mizutani of Japan and Motaleb Akash of Bangladesh.

In America, data revealed by Deadline shows that Disney’s Wish lost $131 million. Meanwhile, the outlet named the Mario movie and Across the Spider-Verse as the biggest and third-biggest American blockbusters of 2023.

The Japanese film Angel’s Egg (1985) will be remastered in 4K under the supervision of its director, Mamoru Oshii.

The governments of Jamaica and Nigeria are developing a partnership to boost “film and animation.”

My Little Boys is a popular animated series in Taiwan, now in its seventh year. Its new season (like its past ones) has been posted on YouTube with English subtitles. Producer Dreamland Image is reportedly building to a feature film.

In Japan, a 10-year-old student created a short piece of stop-motion animation — which went massively viral. Watch it here, or see a write-up about the whole thing here.

Lastly, our article Miyazaki, Disney and Eisenstein looked into the art of directing animated films.

See you again soon!

Giannalberto Bendazzi wrote this about Windy Day in the second volume of Animation: A World History.

The Hubleys first took their daughters to a recording studio a few years before the Windy Day sessions — those earlier tapes were eventually used to create Cockaboody (1974).

An article published in Wisconsin’s Post-Crescent (March 5, 1972) put the recording session at two hours. By contrast, John Hubley mentioned three hours in a 1973 interview with Screening Room (which we’ve used as a source a few times in this issue).

In a long section on Faith Hubley, the book I Can’t Do What? outlined the general process that the Hubleys used for their films:

The Hubley collaboration, who did what, could not be defined easily nor described, she said. They worked on the storyboard, a visual scenario, together. Then moved on to the sound and score. Her husband, she said, did most of the drawing, although she would draw her ideas. They designed the characters together and agreed on the layouts.

In an earlier interview for the book Women Who Make Movies, Faith described it this way:

We collaborate on the story. John does most of the backgrounds and I do some. I do the character rendering. We both work on the sound tracks. As a trained editor, it’s easier for me. The statement, the content, is made jointly.

From the interview with Faith and John Hubley in The American Animated Cartoon: A Critical Anthology, which we’ve used several times here.

From a profile on Barrie Nelson in The Calgary Albertan (August 15, 1978).

From The Montreal Gazette (October 20, 1966).

From the Abilene Reporter-News (September 8, 1968).

From the Hartford Courant (March 13, 2000).

Today’s lead story is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on March 3, 2023.

Wow. There really is no one way to work in this medium.

Terrific! The picture of the family was priceless! WOW! Loved the water color and the whole story!