A Legend's Animated Wool

Plus: newsbits.

Welcome! We’re here with a new Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Our slate goes like this:

1) Animating with wool.

2) Newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1 – Making wool live

One of the finest artists ever to touch stop motion remains Hermína Týrlová. She was a Czech who was born in 1900 — and who lived until 1993.

Týrlová co-founded Czech animation in the ‘20s. Her stop-motion films were popular and highly decorated by the ‘40s. It wasn’t until the late ‘50s, though, that she fully hit her stride. It happened with The Knot in the Handkerchief (1959), about a piece of cloth that feels like a living thing. From that point, telling stories with odds and ends became her specialty.

In 1960, Týrlová turned 60 years old. Yet she was only getting better. One critic described her as that rare case: an artist who manages late in their career to “renew their creative ability to the extent that they create the highest and best work of their life.”1 Around this time, Týrlová’s wool series began.

It was a revelation — a whole new style. To quote historian Jan Poš:

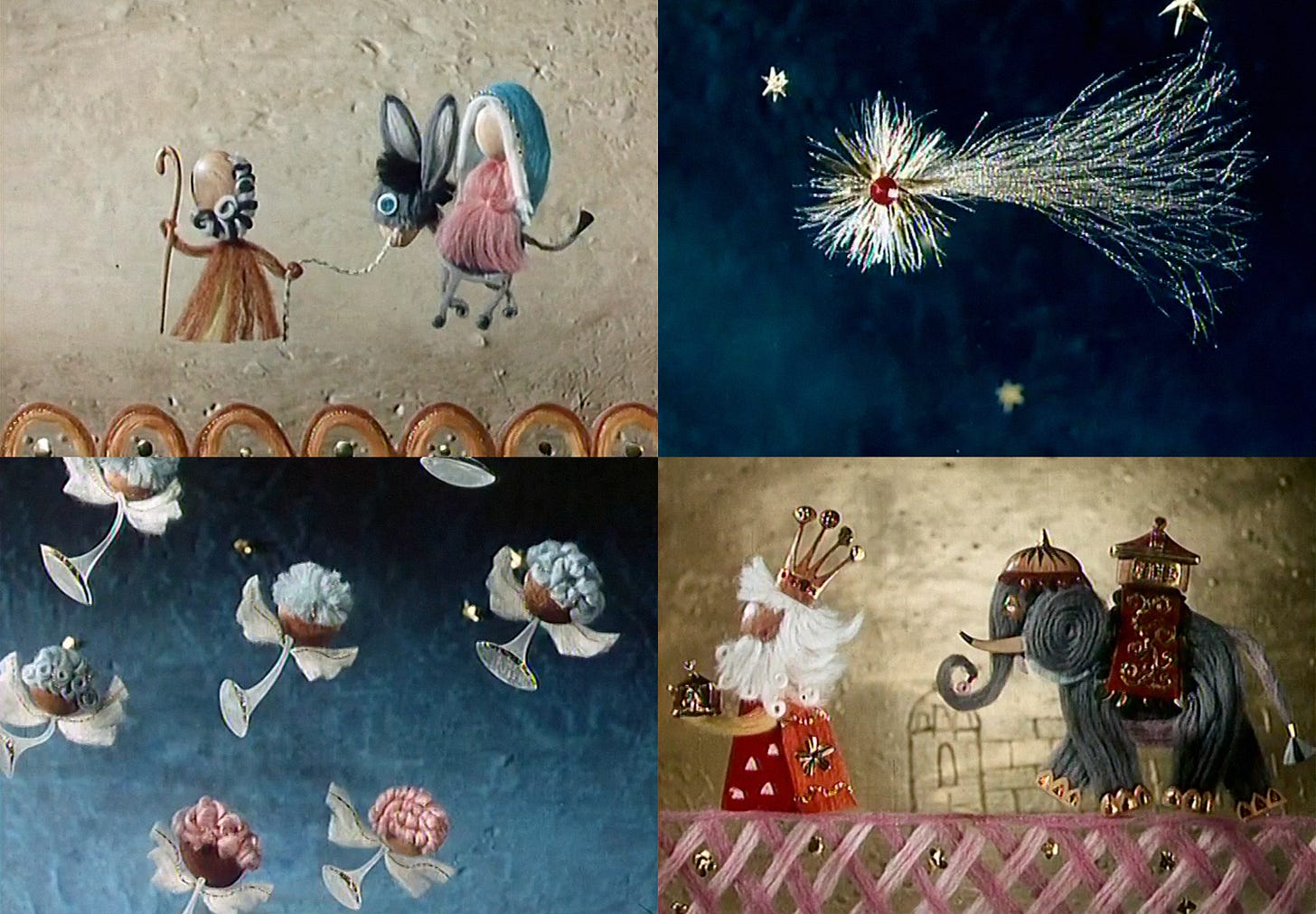

During the period 1963 through 1969, Týrlová created six “wooly” fairy tales, tender ministories, in which the actors were puppets made out of woolen yarn. These pieces represent perhaps the best of what Czech animation did for its youngest audience.2

Let’s not limit it: Týrlová’s wool films hold interest for all ages. They’re beautiful, odd, mesmerizing things.

Some have asked — why wool?

In her golden years, the hunt for new materials guided Týrlová’s process. Before she knew what to do with wool, what its most effective use might be, it seemed promising. As she explained, “I discovered a fondness for the material, and that was all.”3

Her first major attempt with it was Two Balls of Wool (1962).4 There, the contents of a sewing kit come to life. A pincushion becomes a horse; a tape measure becomes a snake. Týrlová noted that her goal with the film was “to animate only things, with no puppets” (emphasis added). Its heroes are balls of yarn that morph themselves into doll-like shapes — and then cause trouble.

It’s a simple, lovely piece that’s more about play and imagination than story.5 Wool was just one of the many materials used in it, though. Afterward, Týrlová and her team pushed further — past these two yarn characters, and into a film made almost entirely out of loose strands of wool.

The step toward an all-wool film took preparation. As Týrlová said:

I tested what could be done with wool fiber. How do you make it move? What can be gained from it for animation? But for that I needed a story. I didn’t have one, yet still I did a trial — a scene of a storm in a desert … In that scene, I tested what I wanted to know about the material. How flexible wool fiber is, how fluffy it is, how it teases and how photogenic it is. Screenwriter Milan Pavlík wrote me a lyrical story about the faithful friendship between a doll and a lamb. At the beginning of the script he wrote, “Don’t look for a story; this is a poem.” And I must say, Pavlík’s script and the results of the first tests with wool fiber greatly impressed not only me, but also the designer [Ludvík] Kadleček and the then-animator Jan Dudešek.6

It all led to one of Týrlová’s great works: A Wooly Tale (1964). The team laid strands of wool onto glass and arranged them into characters — and into poses that look and feel like the way people stand or walk. But the textures are all different, and gorgeous. Týrlová noted that the “wispy line of wool looks magical in the right lighting.”7

A standout scene in A Wooly Tale is that desert storm — the test wound up in the film. It reveals how wool reinforces the story, or makes it possible in the first place. The way the material pulls apart, transforming into gusts of wind and sand, couldn’t happen otherwise. Form and content become one and the same.

A Wooly Tale’s character designs came from the hand of Ludvík Kadleček, one of Týrlová’s main collaborators. Just two animators (including Jan Dudešek, another regular) took charge of the whole nine minutes.

The signature of a Týrlová film is the use of movement to convey character, even in objects without human features. In A Wooly Tale, she and her team did it so well that you nearly forget to notice. Strands of wool seem to be nervous or playful, or determined or compassionate, through their motions alone.

Also important was the music. Composer Zdeněk Liška received special credit from Týrlová here. A Wooly Tale feels like a dream — which his haunting, avant-garde score emphasizes. As the main character wanders the desert, sunrays beat down to eerie electronic bleeps and bloops. When a lion stalks him and his lamb, its roars come out as abstract musique concrète effects.

The film won awards, and it marked the official start of Týrlová’s wool series. Following it were The Snowman (1966), Little Girl or Little Boy? (1966), Dog’s Heaven (1967), The Christmas Tree (1968) and The Star of Bethlehem (1969). All were shot “flat,” with wool strands on sheets of glass under the camera.

Footage from the studio shows the artists animating the characters with tweezers and their fingers. A Wooly Tale was done primarily “on ones” (24 new frames of animation per second), and that stayed the standard. Somehow, it didn’t add jitter. The movement in these films is extremely polished, and even the fuzz at the edges of the wool maintains consistency as the characters walk and jump around.

And yet, despite that polish, the look stays lively and spontaneous. It’s the best of both worlds.

Týrlová wrote that she’d struggled a bit with the “poetic subject” of A Wooly Tale. The wool material naturally tempted her to add “cheerful transformations, animated jokes, surprises,” but they risked clashing with the tone. All of them got to be used more freely in The Snowman (watch), starring the blue-strand man from A Wooly Tale again.

Here, it’s winter, and a snowman comes to life. What happens next is quite a bit different from Frosty — and more surreal. At one point, the lead character falls into icy water and freezes solid. His snowman pulls him out and uses a balloon to fly into the overcast sky, which he unzips to let the sun thaw his friend. After that, they close up the sky by tossing (wool) snowballs at the gap.

The whole film is a string of fun and often wild incidents — all making careful use of the material.

This type of wildness continued in Little Girl or Little Boy? and The Christmas Tree, where the blue character returns (now as a married father). In the former, a stork carries twins to him and his wife, but not before stopping in a river. When the twins end up in the wool-water, a squirrel has to unravel it until dry land emerges from below.

Týrlová wrote these wool films herself, without drawing from children’s literature (as she’d often done in the past). There was no choice, she said — books didn’t have the kinds of “unusual” stories that she believed would suit this material.8

“Each material in itself evokes a particular mood,” she noted. And wool, as she used it, had specific advantages and drawbacks in the stories it could tell. “Wool is delicate, tender and malleable,” she said in 1970, “but it is still far easier to imprint a specific expression on a puppet or a ragdoll than on a figure made of wool.”9

Her wool films get tremendous personality out of the material, but they do it carefully — by avoiding their own weaknesses. Dialogue is sidelined, and the stories are kept simple, each one more like a series of events than a grand narrative.

Some of this changed, though, in The Star of Bethlehem. It’s been called the pinnacle of Týrlová’s wool films, and its story is much more complex. It’s a retelling of the nativity.

Týrlová had sat on the concept for The Star of Bethlehem since at least the ‘40s. By her account, she wasn’t religious — the film grew out of her deep childhood connection to this topic. “It contains memories of my father’s carved nativity scenes, of how I played with those figurines and sheep,” she said about this project.

Týrlová hadn’t been planning to continue the wool series. After The Christmas Tree, she felt the material “would not give [her] any new possibilities.” The Star of Bethlehem, whose final script she co-wrote, was originally meant to take a different approach.

But A Wooly Tale’s composer convinced her to do one more. Hearing the concept for The Star, he said, “You’re going to make it out of wool again, aren’t you?”

And so she did — mostly. Ludvík Kadleček, a designer for the whole wool series, added new materials like tinfoil. And he carved each character’s head out of wood, in such a way that the tree rings create the sense of facial expressions without any extra features. Paired with the wool, the effect is wonderful. Týrlová said that Kadleček delivered the “glorified simplicity” she wanted.

The Star was the official end of the wool films.10 But Týrlová did return to the material later, in another form, for her series From the Diary of Tomcat Blu-Eyes (1974–1976). The characters in it are crocheted wool, and the effect is a surprising change from the wool strands she’d used up to then.

It’s proof that she was right: whatever material you use “evokes a particular mood.”

A lot of the magic of Týrlová’s films lies in her special awareness of the stuff with which she worked. It becomes part of the story — part of the whole point. Loose strands of wool feel light and ethereal, and she leaned into those feelings. In her wool films, she closed the space between medium and message.11

2 – Newsbits

We lost Ferenc Sajdik (95), who worked on the famous Moto Perpetuo and other cartoons in communist Hungary.

I Am Frankelda now has a trailer, ahead of its wide release in Mexico next month. Guillermo del Toro wrote that the film’s creators “have aimed for the top — and they have reached it.”

In Indonesia, the trailer for a student film called Ikan Mas Tur Dedari exploded on social media and hit the national news. Director Adhistya Sedana and his team spent 13 months on the project, which runs 15 minutes. See the trailer on TikTok.

Australia’s Alex Grigg explained how to animate a transformation without really showing it.

In America, control of TikTok is being handed to powerful allies of the government, after months of illegal extensions to ByteDance’s deadline to divest the platform.

Japan’s Infinity Castle has earned more than $600 million worldwide. Given that it was already the highest-grossing film ever produced by the country, it’s beating its own records at this point.

In Canada, the Ottawa Animation Festival handed out awards to Death Does Not Exist, Desi Oon and The Night Boots. See the full list here.

Lamput’s fourth season is up for an International Emmy. Vaibhav Studios in India is behind the show, but creative control of this season was also divided among teams in Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

In Britain, MAF revealed its festival program for 2025. On the slate: I Am Frankelda, Cartoon Saloon’s Éiru, Angel’s Egg in 4K and more. (The very funny Alasdair Beckett-King will host the award ceremony.)

In South Africa, the Durban FilmMart released a new call for animated projects. A few months ago, its top prize and grant for animation went to Crocodile Dance, a film we’ve covered.

Last of all: we looked into the development of Mamoru Oshii’s idiosyncratic filmmaking theories, influenced by New Wave, Osamu Dezaki, Andrei Tarkovsky and more.

Until next time!

From Jaroslav Boček’s 1964 article “Hermína Týrlová,” as it appears in the book Animation and the Times (Animace a doba).

From Krátký Film: The Art of Czechoslovak Animation.

From the fourth part of Týrlová’s memoir “Z klubíčka vzpomínek,” published in Film a doba (December 1964), used a lot today.

Týrlová noted that Two Balls of Wool was the start of her wool films in “Kouzelnice z říše loutek,” an interview published in Vlasta (October 25, 1978). Note that she’d done another film with woolen yarn, A Night’s Romance, earlier in her career. But, there, the characters were still in the realm of traditional puppets.

František Tenčík made this point in his book Hermína Týrlová (1964).

From Marie Benešová’s book Hermína Týrlová (1982), our most important source for the piece.

Quote from Ahoj na Sobotu (1970, no. 52).

From Práca (February 21, 1976).

From Zábĕr (July 9, 1970).

See Zábĕr (December 19, 1980).

An earlier version of today’s story was published behind the paywall on March 28, 2024.

I've seen you post notes about her work before, but this is a wonderful deep dive and made me so happy to read it...and feels a bit nostalgic, too, I guess that's the 'childhood' feeling of it.

Wow!!! Really beautiful work, I'm definitely going to watch the full films.