Happy Sunday! We’ve got an exciting issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter in store for you today. It goes like this:

1️⃣ The Knot in the Handkerchief by Hermína Týrlová.

2️⃣ International newsbits.

3️⃣ Retro ads by Studio Ghibli.

Our newsletter goes out Sundays and Thursdays. If you haven’t yet, you can sign up for free to receive our Sunday issues in your inbox, every weekend:

Now, let’s go!

1. Living things

People call Hermína Týrlová “the mother of Czech animation.” That title makes her work sound a little dated. It implies that she was an early pioneer outpaced by later, better directors. It erases how specific and strange her films still are.

It also erases the fact that Týrlová was active for most of the 20th century. Her career began in the 1920s and ran through the ‘80s. She directed some of her greatest films in her 60s. For comparison, the Czech master Jiří Trnka (1912–1969) worked in animation for under 25 years. Týrlová made films before him, and continued long after him.

But what kinds of films? That’s tricky to answer, because Týrlová was different. Like many Czech animators, she worked in stop-motion, but her films are often more about play than story. She takes the mundane, the everyday, and makes it feel alive. “My goal is the ‘revival’ of inanimate things — toys, puppets and unimportant objects,” she once said.

Way, way before Luxo Jr. or Toy Story, Týrlová made imagination-sparking films about living things. Not only toy soldiers and dolls (although she did use those), but strands of wool, kites, unopened letters, toy trains. Each had its own, special personality.

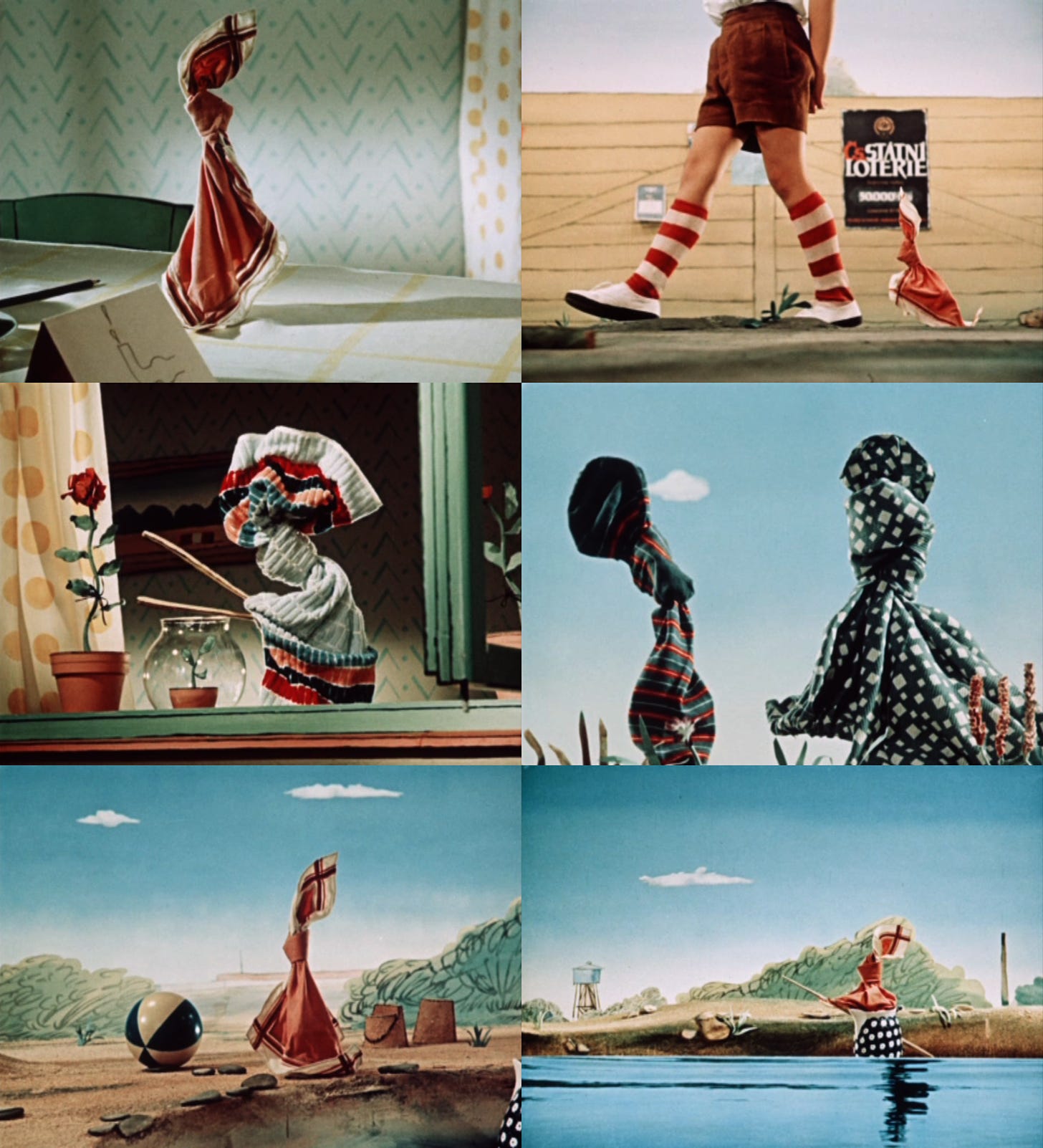

Which leads us to The Knot in the Handkerchief (1958) — a film that changed the course of Týrlová’s career. It stars a knotted handkerchief that is, somehow, fully alive.

The story of The Knot in the Handkerchief is simple, but it hinges on an idea that needs explaining to modern viewers. At the time, knotting a handkerchief was a way to remember something — like a string around your finger.

In this case, the knotted handkerchief exists to remind a young boy to call the plumber. His mother leaves it on the table with a note — the faucet is leaking. When the boy sets out, though, a soccer game distracts him. The knotted handkerchief escapes his pocket to cause trouble around the neighborhood, failing its one duty: to remind.

This concept had existed since at least the ‘40s. “The Knot in the Handkerchief is a very old one,” Týrlová said in 1979. It wasn’t a plan for a story — just a thought that she could turn a handkerchief into a character. (Týrlová’s choice of physical material drove many of her films, guiding her other decisions.)

For years, she didn’t try it. “I was afraid to film it for a long time,” she recalled. This was a character without a face, or hands, or limbs of any kind. She hadn’t done anything quite like it.

As time passed, she decided to revisit the handkerchief idea in test form. The results were promising — and the challenge, as always, excited her. Týrlová once explained:

It gave me great delight to bring puppets to life, using animation to create their characters, their “mental” states and relationships with the other puppets, with whom they experience different feelings in their play together (joy, fear, anger or contempt). And [that delight] was greater the more difficult it was to put across these feelings. A good and tough result gave me great satisfaction.

Under Týrlová and her collaborators, The Knot in the Handkerchief took shape in the late ‘50s — when Týrlová herself was in her late 50s (she was born in 1900).

The team worked in the city of Zlín, at a state-owned studio. Besides Týrlová, a few other key talents on the film were Josef Pinkava, who directed the live-action parts, and designer Kamil Lhoták. Týrlová called it a broad collaboration. She wasn’t an ego-driven filmmaker — allowing others into the process was part of her process.

“When someone came up with an idea, the others discussed it,” she said about The Knot, “everyone added something to it, and thus it gradually crystallized into its final form.”

Sure enough, there were huge challenges. Many stemmed from the mix of live-action and animation. They chose this hybrid form to tie the handkerchief to real life, according to Týrlová — “an inanimate thing becomes alive for me in my pocket, too.”

They built sets at a small scale, creating a stylized world where space is compressed even for the live actors. As Pinkava said, they “tried to reconcile the large-scale world with the miniature.” Otherwise, the puppets risked looking too tiny, adrift in human-sized places.

As for the knotted handkerchief itself, it’s more than it appears to be. Really, it’s a puppet designed to look and act like a handkerchief. Describing the thought process behind it, one commentator noted, “The inside reinforcements must not affect its movement, and must be well hidden in every position.”1

Týrlová paid special care to the portrayal of each character through its motion. The handkerchief becomes rowdy and disobedient because it’s copying its owner. She said that she was overjoyed to learn that the thing could “act well” despite its lack of human features — it became one of her favorite creations. And its misbehavior was part of the appeal. “We’re not only good,” she said.

With the other knotted beings, who chase the handkerchief back to where it belongs, Týrlová explained that “it was necessary to distinguish the individual types from each other, to pin them down, to show their character, who is who.” It risked being a jumble otherwise. (Some of them, she noted, were aunts.)

In stills, they just don’t have the same effect. This is above all an animated film — we discover the characters through their movement.

The Knot in the Handkerchief (which you can watch in full above) was a risk for Týrlová. These were arguably her least human characters to date. They’re almost abstract — “magical and mysterious beings” who resemble “figures in colorful cloaks, people with odd physiognomies,” wrote one author. And yet they’re human to the core.

So, the risk paid off — and it dragged Týrlová out of a rut.

Starting with her first major project, Ferda the Ant (1944), Týrlová made lyrical films for kids. As a documentary noted in 1961, “The aim of her remarkable work is to give the best to those she likes the best — children.” Like The Knot, many of these films are playful and near-plotless. The style won her fans, but detractors as well. During the mid-1950s, she spent a few years listening to her detractors.

“I was criticized at the Artistic Council in Prague, told that I was ‘still playing with my little feelings’ and that I should prove myself,” Týrlová remembered. “So I went for it.”

Her turn toward more typical animation had made her unhappy, and hadn’t silenced her critics. Týrlová always faced sexism in the Czech animation world — on Ferda the Ant, she said, “The studio leadership did not have too much faith in me, and this was doubled by the fact that I was a woman.” The jabs about her “little feelings” had a similar tone. They threw her off track.

The Knot in the Handkerchief was the film that put her fully back on track. It was acclaimed worldwide. Historian Giannalberto Bendazzi called it a “turning point” for her, which led to “a renaissance of her talent.” It opened the way for years of further experiments, in beautiful films like Two Balls of Wool (1962) and The Blue Apron (1965). The play and lyricism were back, stronger than ever.

Watching the characters in The Knot move is a wonder. It’s a sense that only a Týrlová film can deliver. These are things — handkerchiefs, towels, shirts. But they feel like so much more. Somehow, they’re alive.

2. Newsbits

The renowned artist Manolo Pérez, who ran Cuba’s most famous animation house (Estudios de Animación ICAIC) between 1970 and 1984, passed away in early August. He was 86.

A really nice-looking stop-motion feature from Korea, Mother Land, will compete at the Bucheon International Animation Festival. It comes from Studio Yona and director Jaebeom Park (Snail Man). See the trailer here.

In America, Netflix Animation and Warner Bros. Discovery saw more layoffs this week — roughly 30 people at Netflix, around 100 people in Warner’s ad sales divisions and an unspecified number on Warner’s film Bye Bye Bunny.

And there may be more turmoil coming for American animation — the talk in Hollywood is that Warner Bros. Discovery could sell to Comcast in a few years, according to The Hollywood Reporter.

The Japanese magazine library Oya Soichi Bunko has a new exhibit — over 500 magazines with articles connected to Studio Ghibli. It starts October 9.

In Spain, the “Weird Market” is putting animation projects (and more) in touch with potential partners. Animator JuanPe Arroyo Molina, known for his work on The Amazing World of Gumball, is pitching a short film about a goblin warrior.

The newspaper La Opinión trumpets a “golden age” of Mexican animation, brought on by state funding and co-productions with the US.

On that note, one we missed: a recent behind-the-scenes for the Mexican series Frankelda’s Book of Spooks. It points to a short that’s new to us — the visually stunning Revoltoso, by the creators of Frankelda.

On September 15, Russian animator Yuri Norstein turned 81.

Meanwhile, Russia’s government ponders a bill that would pull state funding from “producers, distributors or cinemas” that “propagandize their anti-patriotic actions, condemn the actions of state authorities and do not support the civilian population of Donbass.”

Lastly, American animator Jonni Phillips started her next project, the second season of her series Secrets and Lies in a Town of Sinners, on Patreon. (Cartoon Brew profiled her career this week.)

Hope you’re enjoying today’s issue! Thanks for reading so far.

Two quick notices. On Friday, we put up episode two of Mee’s Forest, the Chinese Flash series we’re translating (as we outlined last week). New episodes will be added to a YouTube playlist as they’re finished. Meanwhile, on Thursday, we wrote to our members about the mid-century cartoon Flebus. We liked that issue quite a bit.

The last section below is for members, too. We’re exploring two ads produced by Studio Ghibli in the mid-2000s, full of warmth and spirit. You’ll find concept art and storyboards, too.

If you’re a member, read on. If not, we’ll catch you next week!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.