Happy Sunday! The Animation Obsessive newsletter is back with another issue. Our agenda:

1️⃣ On the Slovak classic Brigand Jurko (1977) by Viktor Kubal.

2️⃣ Animation news from around the world.

3️⃣ A final note.

New here? It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — you’ll get them in your email inbox each week:

And now, we’re off!

1: Sketching folklore

Brigand Jurko is one of the essential animated feature films made in the former Eastern Bloc. It’s also one of the hardest to describe. There’s nothing quite like it.

The film dates to 1977. It’s about a bandit who robs the rich and gives to the poor. It’s part-comedy, part-drama, part-tragedy, part-romance, part-musical, part-myth and part-fairy tale. And it was nearly all the work of one artist: director Viktor Kubal, the sole credited screenwriter and animator.

As Kubal explained, “I have to deal with 48,000 pictures myself.”1

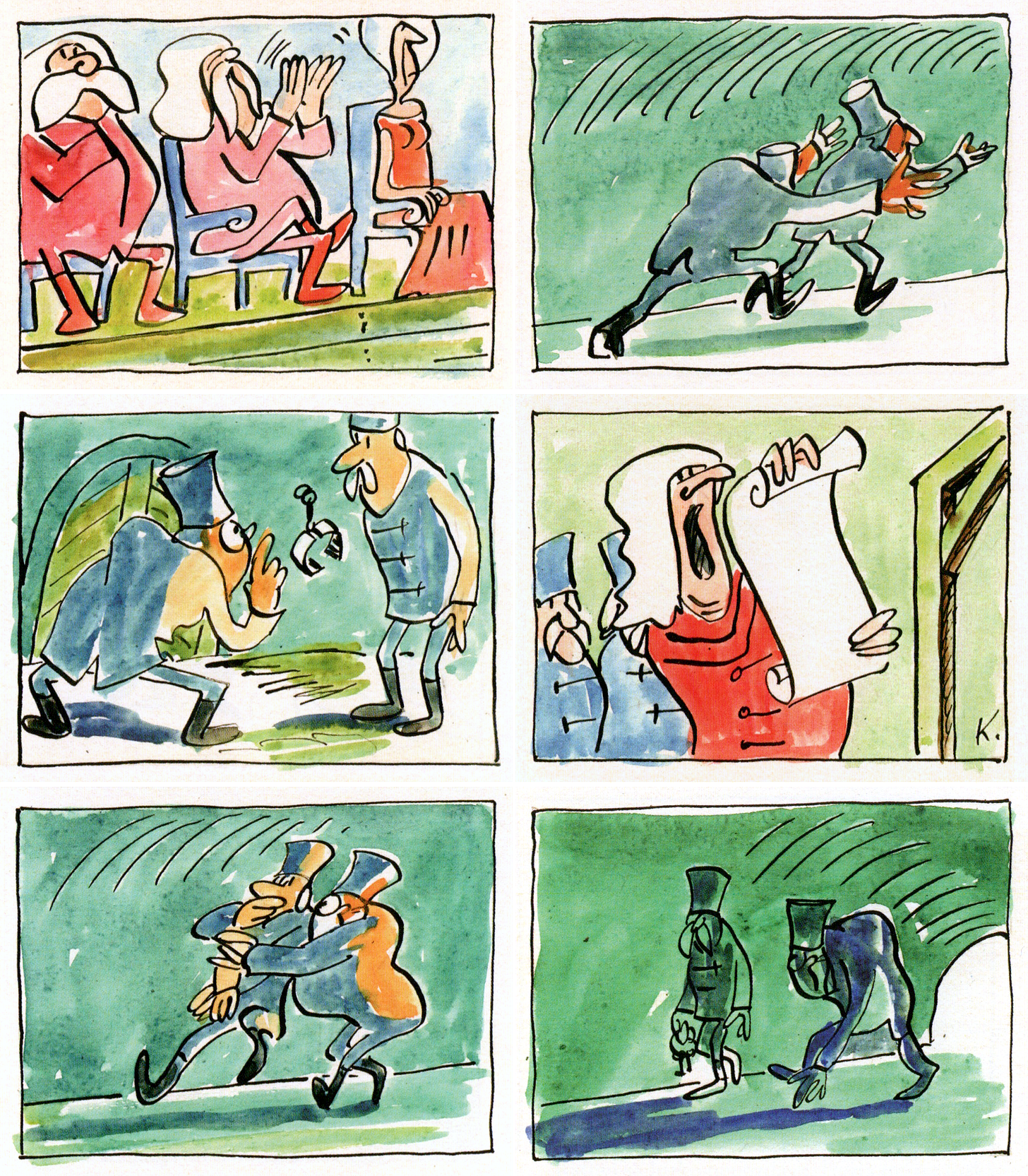

Few besides him could’ve handled the job. Kubal was a veteran of solo animation — it was his way. Even though he worked with colorists and composers and camera operators, Kubal films are always clearly Kubal films. They have his sense of humor and his loose, doodly art style.

Brigand Jurko has them, too. The film rejects the rules of animation and of traditionally “good drawing.” It doesn’t feel like ‘70s cartooning: it’s weirdly modern, almost like it’s from the internet era. When we shared a clip of it last year, animator Kai Ikarashi (Promare) replied, “Even if I was told that it was made yesterday, I would believe it.”

The style derived from Kubal’s philosophy as an artist. He worked quickly, accepting and using for effect what others might discard as mistakes. His goal was to get his ideas across. “I have always considered the content of a drawing to be more important than its form,” he once said. “A precisely drawn bad joke is nothing. But a dashed-off sketch with good content is already something. It is similar with film.”

When Kubal tackled Brigand Jurko, he was already the leading animator in his homeland of Slovakia. It was communist back then, making up the latter half of Czechoslovakia. Animators on the country’s Czech side, where Jiří Trnka worked, often got the attention — but Kubal was a world-level artist in his own right.

And Brigand Jurko made that clearer still. It was a huge accomplishment: the first feature-length cartoon ever produced in Slovakia.

This was a dream project for Kubal. He based it on the folktales surrounding Jurko Jánošík, a Slovak highwayman who lived in the 1600s and 1700s. Myth and history are tangled up in Jánošík’s story, which has been retold for centuries. He became a national icon — a kind of Robin Hood of Slovakia. Kubal had grown up with the legends about him.

Then the opportunity came to animate them, as Kubal said:

At a time when I had already made about 60 films [...], the dramaturge Rudolf Urc came up with the idea of filming a full-length cartoon at the animated film studio in Bratislava. It was a very daring idea, but not infeasible, especially since I had been carrying in my head for many years a subject that I’d wanted to realize even in my early teens. It was the legend about Jánošík. In my youth this topic fascinated me already as a schoolbook character, full of justice, generosity, goodness and, above all, romance. A character made for a cartoon.

In those years, Jánošík had been repurposed as a symbol of class struggle. But Kubal and Rudolf Urc wanted to go in a different direction. They looked to fairy tales — to the versions of Jánošík tied to magic and classical hero stories, rather than patriotism. They put Jánošík’s first name, Jurko, in the film’s title to suggest “childish innocence or playfulness.” He’s not a grand historical figure, but a familiar storybook character.

Planning began in early 1974. Kubal and Urc worked together to sort out the project’s themes. “We chatted for whole days about this topic,” Urc wrote, “and (especially) about the genesis of the motifs, about their historical, folkloric, mythological and fairy tale context.”

They imagined a Jurko who has a magical belt, who gets help from a fairy — ideas from the folk tradition. This met with criticism from certain quarters. After all, what need did Jánošík the proletariat revolutionary have for the supernatural?

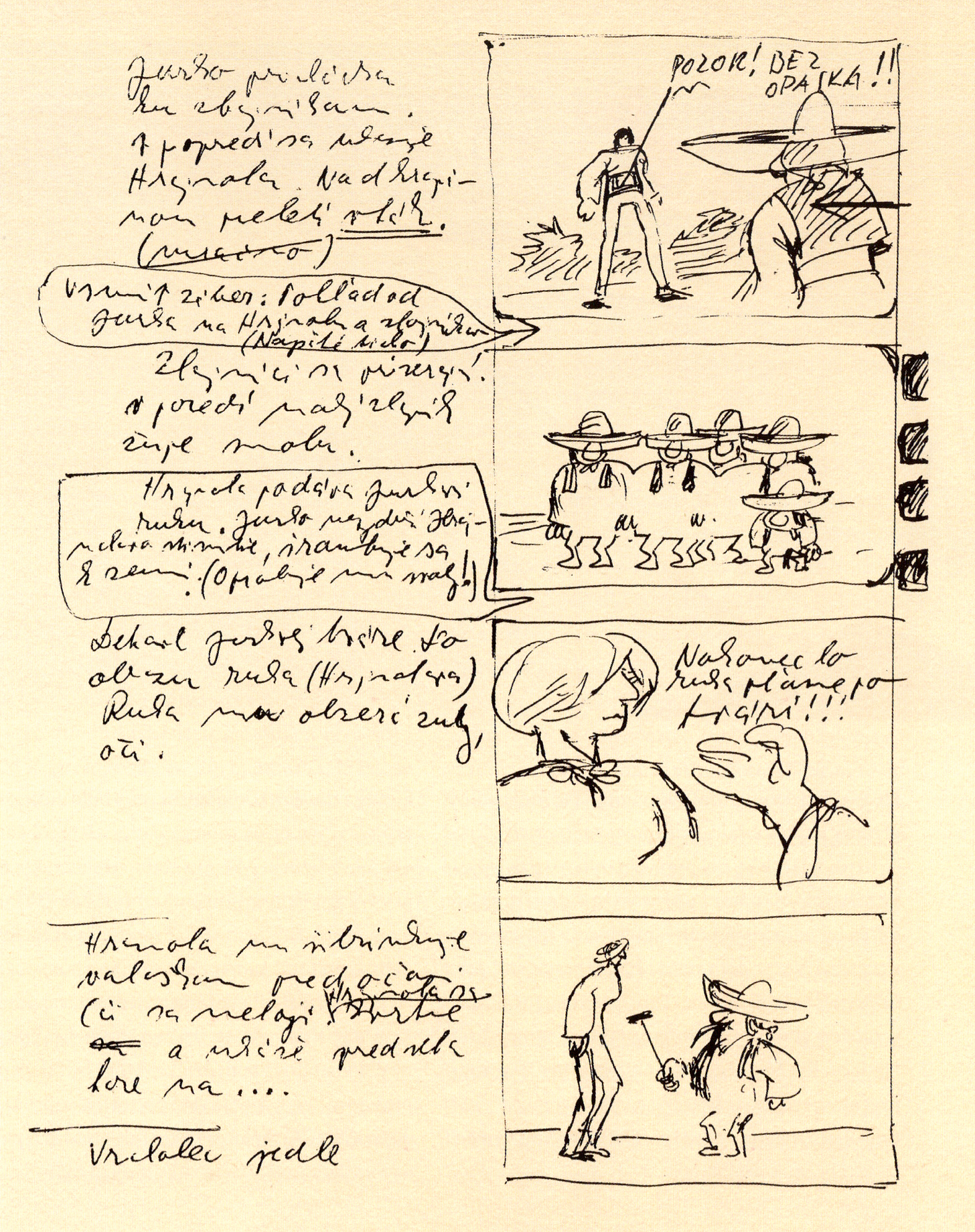

Always a fast creator, Kubal spent just a few days writing the story outline — five pages. Then, in April 1974, he started on the script and storyboard. The boards took him a mere few months, yet they comprised more than three hundreds images in color, almost as detailed as the film itself.2 By May, Kubal was already animating, and his work was already being filmed.

Something important to note about Brigand Jurko is that it’s a story, often a serious one, told chiefly in gags. That includes pratfalls and slapstick, but also the surreal, dreamlike visual gags of cartoons from the ‘20s and ‘30s. To climb from a tree onto a windowsill, Jurko might use the moon in the sky as a stepping stone.

It’s a style unique to Kubal. He’d developed it in an odd way.

Born in the ‘20s himself, Kubal became an early fan of Fleischer Studios, emulating its work. Disney’s films interested him less, and, by chance, he didn’t see Snow White until decades after its first run in Slovakia. “So, apart from Fleischer, I had no role models and I didn’t even study the evolution of animated film in more detail,” he said.

He combined that sensibility with years of work as a magazine cartoonist, where he honed his tossed-off drawing style. All of it went into his films. Kubal became an ace at gags — the more the better — drawn in a crude and simple way. If you know the work of Priit Pärn (Time Out), it’s in that ballpark.

Brigand Jurko added extra layers to Kubal’s style, though. It’s built on comedy techniques — but it’s not strictly a comedy. Kubal felt that a feature film demanded more: “it is not enough to just laugh and just cry.” Brigand Jurko often makes you laugh, but that’s not all it does.

The fairy winds a water ripple into a ball of water-yarn, and you’re not sure whether it’s funny or beautiful or both. You’re sobered as Jurko hits rock bottom, whipped and defeated by the villains and left for dead. (For that scene, Kubal played Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony for his composer as reference for the music.3) Many of the songs with lyrics, like the execution chant or the closing folksong, are genuinely stirring. The same is true of the score, recorded at Kubal’s request with a symphony orchestra.

Couple that with the visible arthouse influence in some of the cinematography, and what you’re left with is close to indescribable. That’s Brigand Jurko.

The tonal balance makes no sense and logically shouldn’t work. Kubal struggled with it, trying to fit comedic characters (like Jurko’s bandit crew) with serious ones (like Jurko and his lover Annie). He felt that it would destroy the story to make the serious characters too jokey and cartoonish — and yet making them too realistic would be dull. Somehow, he found a way.

As always, Kubal worked fast. Having started animating around April or May 1974, he completed the final shot in December 1975. He’d just drawn a 76 minute film essentially by himself, supported by an ink-and-paint crew.

His process was slapdash. Many, many scenes from the script were changed on the fly. Assistant director Anna Kubalová, who was married to Kubal, recalled:

Like all of Kubal’s scripts, the script for the film Jánošík was only a kind of “skeleton” of a script. The actual plot of the film was created directly while drawing individual shots on tracing paper. Often it happened that a shot ended up completely differently than it was in the script. It must be said, Kubal honestly noted down on the original script the changes and additions he made, so that the individual pages were written more by pen than by type. In the end, the whole script looked like a pile of written, shapeless paper.

This was how Kubal worked — raw creativity, as fast as he could go. He flourished when he made in the moment, drawing from his never-ending flow of ideas.

But he also used methods on Brigand Jurko that you might not expect. He took regular trips to Terchová, the village where the real Jánošík was born and where Kubal spent several years of his childhood. He said, “[W]eek after week I travel to Terchová to sketch a stream or a tree or a rock, to make it truly Terchovian.” His hundreds of background paintings for Brigand Jurko came in part from life. (He animated with a mirror, too, like a Disney artist.)

The shooting of Kubal’s animation was completed in April 1976, two years after the project began. After post-production, Brigand Jurko debuted in Slovakia in March 1977. The result was a canonical work of Slovak animation, both popular and praised.

It’s also a work with a powerful wholeness of vision. Spending 76 minutes in the world of one artist, especially one as idiosyncratic as Kubal, isn’t often possible. By the halfway point, it’s hard to believe that Brigand Jurko keeps going — and going and going — without falling apart or running out of ideas.

This is one of the hardest-to-place films we’ve ever seen, and it continues to defy expectations in 2023. It’s not for everyone — it’s far too messy and chaotic for that. But it does earn its spot among the great Eastern Bloc animated features, like Hungary’s Son of the White Mare. For the adventurous, it’s easy to recommend.

2: Newsbits

In Japan, the stop-motion pilot film Hidari will have special screenings in Tokyo and Osaka theaters later in April. One will feature a talk with Mamoru Hosoda (Belle), who says that Hidari “open[s] the door for new stop-motion animation.”

The Indian studio Eeksaurus took home an American prize at the Clio Awards, the Oscars of advertising, with its excellent claymation ad for JSW Steel.

In South Korea, Suzume is now the biggest anime film of all time, with around 5 million theatergoers. Its revenue (roughly $36.9 million, per Kobis) surpassed that of The First Slam Dunk. Suzume also premiered in America — with modest returns so far.

Anime News Network has an interesting deep dive into the complexities of Japanese co-productions with outside countries.

America’s Super Mario Bros. Movie continues to blow up, earning $678 million worldwide (North America accounts for more than half of that figure).

In Turkey, artists from Iran and Eastern Kurdistan created an animated political ad for the progressive Green Left Party, ahead of next month’s elections.

Dogs Smell Like the Sea is now free to watch on YouTube — it’s a film that impressed us when we saw it in 2021, produced by School-Studio Shar (Russia).

Cartoon Network Africa has a new series, Junior, spearheaded in France and written in Togo.

Two interviews about the Ukrainian film Mavka. Producer Iryna Kostiuk says that it was made in English first to increase its global sales (its Ukrainian dub remains a hit in domestic theaters). And director Oleg Malamuzh argues against the idea that the film is too upbeat:

... the happy ending here is not just a template, about which you can say, “That’s what everyone does.” This is precisely what builds in a child and in the whole nation the desire to live on. I was at a lecture for theater students and I said: if you can tell a story that inspires, do it. Now such stories are very much needed. Because there are enough fears, worries and traumas nowadays. And we have to counter this with positive thinking.Lastly, in an extra-long issue of our newsletter, we explored the tangled history of America’s outsourcing machine. This is one we’ve wanted to write for a while.

3: A final note

One last thing before we go.

This week, Substack released its Notes feature. It’s a little like Twitter-inside-Substack — a space for newsletter writers and readers to interact in short form.

So far, we’re liking Notes. We see it as a companion to our full issues. The format allows us to share things that don’t fit in the newsletter, like peeks inside our book collection, one-off film recommendations and fun tidbits we uncover in our research.

We’re signing off today with a note we posted this week: a storyboard page drawn by Satoshi Kon for his film Dreaming Machine. The image didn’t make it into The Lost Projects of Satoshi Kon or The Plan for Satoshi Kon’s Final Film, our issues that discuss Dreaming Machine, but it’s still absolutely worth highlighting:

Until next time!

As quoted in the 2010 book Viktor Kubal: Filmmaker, Artist, Humorist (Viktor Kubal: filmár – výtvarník – humorista) by Rudolf Urc. This is our source for the majority of today’s article.

Kubal is quoted as spending a few months on the storyboard in the 1994 book Slovak Animated Film (Slovenský animovaný film), co-written by Urc.

The composer of Brigand Jurko, Juraj Lexmann, mentioned this in a recent interview.

A wonderful introduction to an unappreciated genius - looking forward to gobbling up “Junko”! Where did you find the book on Kubal, though? I’ve been doing a wee trek for it online to no avail. It’s in Slovak but I’ll still want to have it in my library to drool over…

Thank you very much for this interesting piece of work. I was in particular caught by the Kubal process and the personal and fast production aspect of it. // overall your newsletters are dense & varied and I learn a lot. Thank you. This Sunday morning, I have been scrolling to see whether you had written a special paper on cut out animation. Maybe you have but I did not find it. I even asked chatGPT of this topic, but the granularity of this knowledge can only be dealt by animation specialists like your selves. chatGPT pointed out some landmark production but misses the pearls. No hurry, nor worries. Take care and have a great Sunday. Karim from Paris