Welcome! Today’s edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter is all about Satoshi Kon, and the projects he didn’t make.

This is a companion to our Sunday issue, The Plan for Satoshi Kon’s Final Film, where we laid out the ideas behind Kon’s canceled Dreaming Machine. We’re digging a little deeper this time, highlighting several other unmade Kon projects — alongside extra details on Dreaming Machine that we didn’t include last time.

Kon worked on plenty of stuff that never saw the light of day. On his old blog, for example, he described his Tokyo Ghost idea — about a homeless person who met a spirit. (It became Tokyo Godfathers.) Then there was the untitled film about a Japanese soldier who fought in the Indonesian National Revolution, which fell apart when Kon learned about Merdeka 17805 (2001), based on the same premise.

That’s not to mention the failed projects where Kon worked for hire — like Gainax’s Uru in Blue (Kon did model sheets).

Today, though, our main focus is on Kon projects where we have access to his concept art. They start in the mid-1990s and run through his time on Dreaming Machine, a film conceived in the mid-2000s. Enjoy!

Phantom

Given Kon’s posthumous fame, it’s easy to forget the actual context of his career.

Before Perfect Blue, Kon was a workaday artist — talented, but basically unknown. Even after that film, he stayed a marginal figure in Japan with a relatively short list of allies. Kon wasn’t a hitmaker and, as Toonami co-creator Jason DeMarco has written, “wasn’t well-liked within his industry.”1 Animator Aya Suzuki once recalled:

[Kon] said he himself is always in his movies. Especially with Perfect Blue. Mima is Satoshi Kon. The psychological torment that Mima is going through is the torment he has experienced with the politics of the anime and the comic book industry.2

This is the background to keep in mind when you look at Phantom, a direct-to-video animation (OVA) that Kon developed in the mid-1990s.

Kon was hustling in the OVA scene at the time. His first directorial credit came on an episode of the JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure OVA series, released in 1994. (Perfect Blue itself was an OVA when Kon joined.) With Phantom, which Kon planned during this period, he wanted to do an original story in four straight-to-video episodes.

The proposal for Phantom didn’t get off the ground, but Kon explained the gist. To quote his comments in the book Kon’s Works:

… it was about clone experiments and psychic powers — a science-fiction story that would unfold over time. It would use some of the standard SF tropes and keep you in suspense over who was the “copy” and who was the “original,” with false memories and everything. That kind of motif was popular at the time.

In his manga work and his script for Magnetic Rose, Kon had already revealed himself as a writer with a knack for psychological thrillers. The Phantom project sounds like a traditional story in that vein — with a sci-fi twist (not unlike Magnetic Rose). Here was Kon’s plot outline for Phantom:

Characters with special powers called “automata” hunt the clones, who hunt the originals. It is going to be a wild manhunt full of incredible action. Some of these originals find out they are actually copies with implanted memories. Then they have to deal with the trauma of that and try to uncover the source of their false memories.

The outline wasn’t groundbreaking — but that doesn’t tell us much about how Phantom would have turned out. Kon was a master of execution, no matter his subject. (He wrote that Perfect Blue’s concept didn’t even interest him. In many ways, he worked against the original material to make the iconic film we know.)

Although Phantom didn’t move forward, Kon himself continued to advance in anime. Soon, Madhouse selected him to do Perfect Blue partly based on his JoJo work — setting the trajectory for the rest of his career.

Reverse and a video game

Although Perfect Blue won acclaim outside Japan, and inspired foreign filmmakers, the film hadn’t elevated Kon much in the anime world. “Perfect Blue didn’t really receive the recognition of the industry,” said Masao Maruyama, the film’s producer. “It was pretty humiliating.”

While Perfect Blue wasn’t a success at the box office, Kon still found himself developing ideas for future projects in the late ‘90s. Reverse was one of them.

In Kon’s Works, the notes from Kon give us very few details about Reverse, except to say that it was a feature film. “I was working on a few things,” he wrote. “I have a bunch of these left — characters and themes I did initial drafts of.”

But there are still things to glean from the art to Reverse — and the context in which Kon made it.

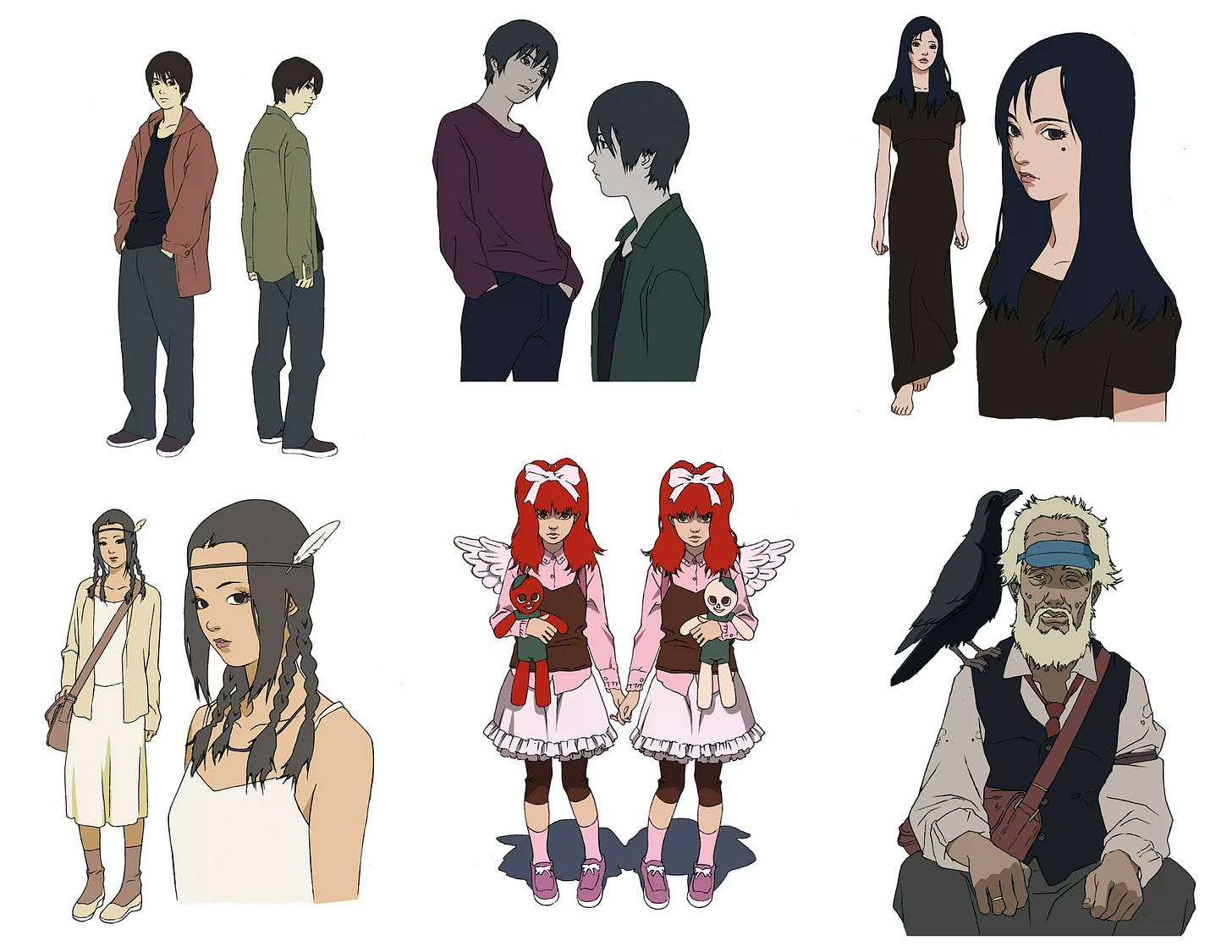

Based on the concepts shown in Kon’s Works, it’s clear that Reverse was another psychological thriller. Kon even designed a pair of twins who echo The Shining. Meanwhile, we find a protagonist who seems in some illustrations to change genders, tying into the title. But there’s no telling what, exactly, Reverse would’ve become.

It’s probable that Kon’s signature trick, dancing on the border between the real and the illusory, was involved. As he said in 2009:

The interaction of reality and dreams is a motif I still have interest in, and I keep bringing it back into my work. Since my debut Perfect Blue [1998] got attention for that motif, I intentionally used it as a central focal point in Millennium Actress, Paprika, and so on.

In any case, it was Millennium Actress that Kon ended up doing, thanks to the backing of producer Taro Maki (a huge Perfect Blue fan). Reverse was shelved.

It’s worth noting that anime wasn’t the only field where Kon found himself after Perfect Blue. In Kon’s Works, he wrote that he briefly connected with the game industry. “I did some preproduction work for a video game in the late nineties,” he explained.

In Japan, it wasn’t that uncommon for artists to cross between anime and games. Yoshitaka Amano (Angel’s Egg) did it freely — and it’s worth reiterating that Makoto Shinkai (Your Name) started as a game artist in the ‘90s. Still, this game project was a bit of an odd detour for Kon. He couldn’t recall anything about it.

“I still have about nine of the character designs,” he wrote, “but I can’t remember who they were or what the pitch was.”

It’s technically possible that this game was made, and that Kon just forgot its name — but we haven’t found it. For now, we’re counting it as a project that never happened.

Dreaming Machine

Our Sunday issue on Dreaming Machine, Satoshi Kon’s unfinished opus, came about by accident. We’d initially planned to cover the film in this piece (The Lost Projects of Satoshi Kon), but our research turned up enough material that it needed its own issue.

Even now, there’s still more to say about Dreaming Machine and what it could’ve been.

The project idea, according to Dazed, came from producer Masao Maruyama. After Tokyo Godfathers (2003), Maruyama simply asked Kon to do something with “a red robot, a blue robot and a yellow robot.” Kon included the characters as cameos in Paprika (2006), his next film, before setting out to do Dreaming Machine.

Unlike with his past features, Kon wrote the script for Dreaming Machine solo. He’d already started by early 2007. The story had similarities to Pixar’s WALL-E (2008) — robots left alone on a ruined Earth, still doing their jobs long after the disappearance of humans, with biblical undertones. Discovering WALL-E was a panic moment for him.

“While I was developing the script,” he told Impact, “I heard about a movie called WALL-E… and I got a little nervous that it might be similar to mine. I can’t tell you how relieved I was when I learned that the two stories were totally different.”

With the script for Dreaming Machine, Kon was breaking away from his past films. Like we mentioned in our previous issue, he dropped his two-tiered, reality-and-fiction storytelling that he’d used since the ‘90s. Why? Here’s what he said in 2009:

… it’s not healthy to keep using the same motif again and again, neither for the audience nor creators — even when utilized in a different context. So I think it’s better for me to steer away from ‘the surreal interaction of reality and dreams’ for a while.

Yet Kon was still making a film with two sides — just in a new way. “Ideally, I want to make it a dual-structured movie, in which children can enjoy it as a fantasy while adults can find the other message in it,” he said. Elsewhere, he called it “a cartoon film [manga eiga] pretending to be for children.”

It was all a way to give Dreaming Machine a broad appeal. Maruyama noted that Kon’s goal was to get “as many people as possible watching the film.” Still, if you look closely, it’s clear that this project was going to be very strange.

Composer Susumu Hirasawa recorded a new version of his 1990 song Dreaming Machine, the film’s namesake, for Kon’s project. If you listen to Hirasawa’s original track while looking at the art made for Dreaming Machine, and remember that it’s all set in a post-apocalyptic retrofuture that’s like Astro Boy gone amiss, you realize something. This film had a zany, warped, almost phantasmagoric soul.

Which was Kon’s intention. He was trying to portray the “shining future” that he’d pictured as a child of the ‘60s, only cracked. Something went wrong — just like in real life, where the 21st century hadn’t played out like people had dreamed. The world envisioned by artists like Shigeru Komatsuzaki, Kon wrote, had been destroyed.

Kon filled Dreaming Machine’s dystopia with this weird contrast. The film’s heroes Robin and Lirico took their names from the retro anime Rainbow Sentai Robin (1966–1967). There was a vehicle based on a ‘50s Cadillac, mixed with Ryusei-go from Super Jetter (1965–1966). Kon wrote that it came to resemble a car from Speed Racer.

Meanwhile, Kon explained in 2008 that he’d started listening to a 120-track playlist of retro, optimistic anime songs from the ‘60s and early ‘70s as he worked.3 He named the playlist “Shining Future” — getting into the spirit of the future of the past, even as he drew it in ruins.

One day, we hope the materials made for Dreaming Machine get released, even if the film isn’t. Per documentary filmmaker Pascal-Alex Vincent, Kon left behind a complete storyboard in his detailed style, and at least 26 minutes were animated. (Vincent wanted to include footage in his Kon documentary, but Dreaming Machine is in legal limbo right now.)

Combined with the music Hirasawa did for this music-driven film, there’s enough to get a feel for what Kon intended. Whether or not it’s ever finished, we may one day get to see the shining, demented future that Kon was building.

Thanks for reading today’s issue! We hope you’ve enjoyed.

One last thing before we go. On Tuesday, we tweeted a clip from the documentary How Princess Mononoke Was Born, which blew up. It shows singer, actor and drag queen Akihiro Miwa in the booth, creating the laugh for the wolf matriarch Moro. It’s an electric moment — with priceless reactions from Hayao Miyazaki and producer Toshio Suzuki. The video got over 2.3 million views and 11 million impressions.

This was our biggest tweet to date. One quote tweet alone topped 125,000 likes, and another passed 70,000. It drew press interest, too — Out did a story on it, which Yahoo! News picked up. There was a piece in NextShark, and the Japanese blog Donguriko took note of the way “people from overseas” had responded to Miwa, an icon in Japan.

How Princess Mononoke Was Born might be the best documentary ever made on animation, but it’s never had an official English release. It’s over 6 hours long (whittled down from 300 hours of behind-the-scenes footage), and it records the making of Princess Mononoke at an astonishing level of detail.

This scene is only a snippet of Miwa’s section — the documentary contains so much treasure, it kind of strains belief. We hope it gets a wide release in English one day.

See you again soon!

Pascal-Alex Vincent, the director of the documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, said something similar last year. Kon himself told stories of how difficult he could be. In the mid-1990s, he was going to be interviewed for the book The Memory of Memories, but he yelled at its editor for misspelling his name. As a result, his interview was cut.

As seen in Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, one of our key sources.

Kon’s “Shining Future” playlist was over four-and-a-half hours long. Among other things, it included Leo’s Song from Kimba the White Lion and a number of tracks from Rainbow Sentai Robin — the theme song, Suteki na Lili and most of all Robin’s Space Voyage, the bombastic track that led to Kon’s fixation on playing retro anime music as he made Dreaming Machine.

Great article. Thank you for sharing. I will search for the Mononoke documentary as well (I had no idea one was made). :) Thanks again.

Hi! I've been thinking nonstop about Dreaming Machine since I read this, I hope I get to see more of it some day. The designs and commentaries give you an idea of what it could've been but the music really brings it all to a new dimension, thanks for sharing!

And speaking of sharing, would you happen to have the Mononoke Hime documentary somewhere? The few copies I've found online don't ship to my country and the only torrent link I found is no longer working x.x

In any case, thanks for a great article!