A Subtle Art with Visceral Power

Plus: animation news.

Happy Sunday! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. The lineup goes like this:

1️⃣ On the niche but important technique of “frame-rate modulation.”

2️⃣ The world’s animation news.

New to the newsletter? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, right in your email inbox:

With that out of the way, let’s go!

1: “I mainly do it for emotional effect”

You’ve noticed it, even if you don’t know it by name.

It’s an animation trick sometimes called “frame-rate modulation.” This subtle art hugely changes the way animated movement looks and feels. With it, animators escape the confines of working strictly on “ones” or “twos” or “threes” — instead mixing and matching freely, to suit their needs.

The name “frame-rate modulation” is confusing. It was popularized in English by the anime critic Ben Ettinger. Back in the 2000s, he defined it as a tic almost unique to Japanese animation, writing this about the ‘60s and ‘70s work of artist Yasuo Otsuka:

… his innovative approach to frame-rate modulation, i.e. changing the frame rate to heighten the impact of action rather than simply following the standard Disney rule of 1 frame/cel during pans and 2 frames/cel any other time, was so influential that it can be said to have become standard practice in the anime industry.

Otsuka’s use of modulation in Horus: Prince of the Sun (1968) often gets singled out. There, he changes his timing on a whim — using “ones” to emphasize the speed of a thrown axe, for example, or slowing down to “threes” to emphasize the scale of a giant. Otsuka knew that different rates had different feels, and he exploited this.

That awareness is common in modern anime. It helps to create the flashy, stop-start look of the fights in Jujutsu Kaisen, but it shows up in quieter ways, too. Director Takashi Nakamura animated most of his beautiful film The Portrait Studio (2013) “on twos,” arguing that “24 frames per second would be too fluid for the mood in the film, and 8 frames per second would weaken the appeal in the image.” Yet he made an exception for the film’s water: he put it “on ones” to give it more dynamism, drawing out its contrast with the rest of his animated world.1

Even so, Ettinger overstated the uniqueness of modulation to anime. Some later writers have overstated it further — treating it as the defining trait of anime motion, and as a separate style from American animation.

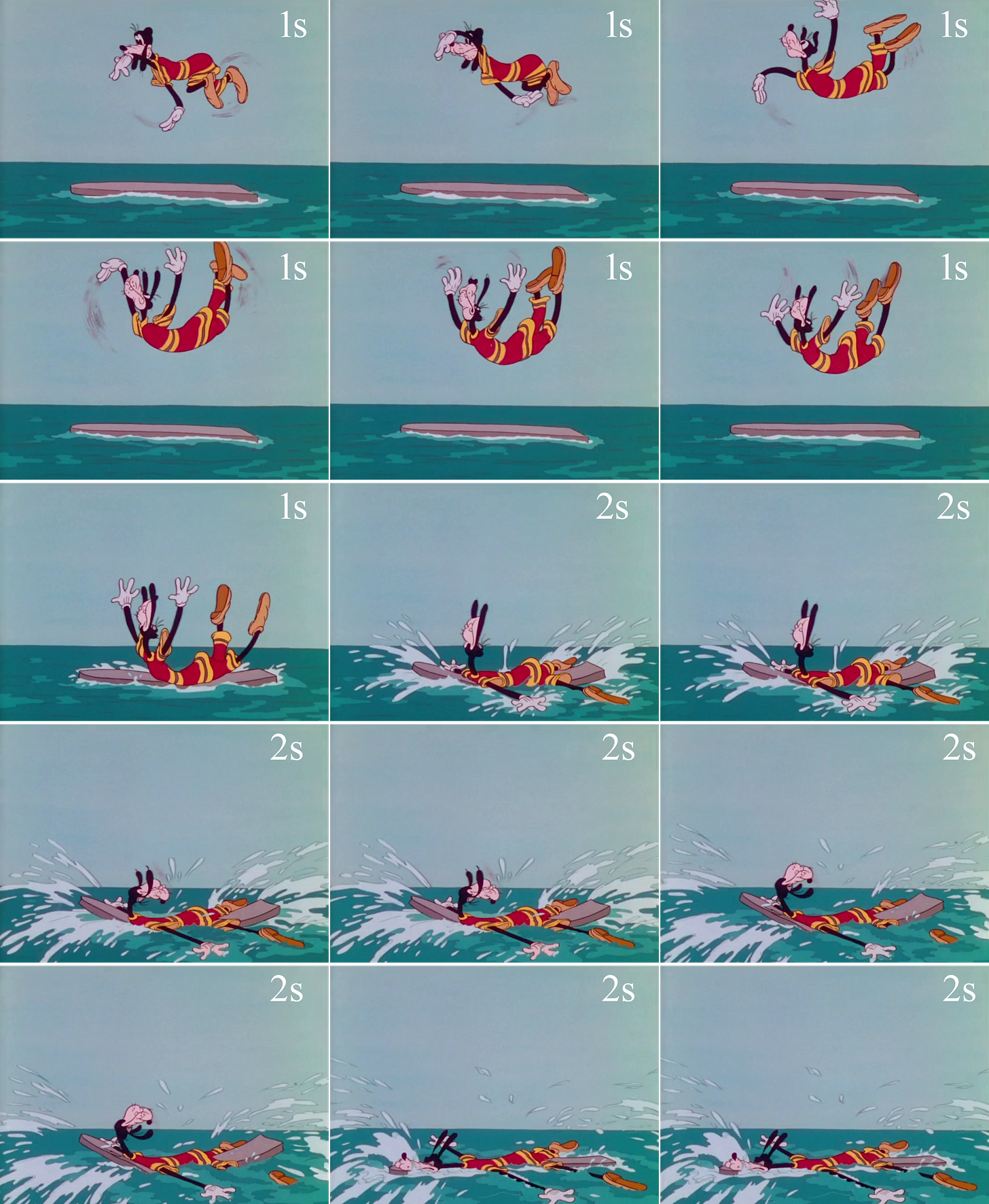

In reality, modulation was key to the timing of American cartoons by the 1930s, and probably earlier.2 Disney used it often in Snow White. You find it in the Mickey short Hawaiian Holiday (1937) as well, which gives us a nice example of Disney-style modulation:

In the scene above, Goofy animates “on twos” as he sails through the air. When he realizes he’s floating, he starts to flail very quickly, and the animators switch him to “ones” to give him a frenzied speed. Then he returns to “twos” as he lands on his surfboard.

Basic Disney modulation had a simple theory behind it. Animator Richard Williams once wrote: “use twos for normal actions and ones for very fast actions.” Most of Snow White is on twos, for instance, but the animators used ones to accent scenes — especially when a character or object moves quickly. At Snow White’s funeral, Grumpy cries on a seamless blend of ones and twos, with his faster motions timed on ones.

For Disney, twos were the default — you saved labor by drawing half the number of frames. That wasn’t the only appeal, either. A number of artists actually preferred the look of twos, keeping “ones” as more of a garnish. Williams said in the 1980s:

Some animators — including some of the top Disney people, Art Babbitt among them — have an argument which runs, “It looks better on twos because it gives you a crackly, crispy look. While ones are weak and soften everything.”

Disney veterans Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston wrote something similar. According to their book The Illusion of Life, the Disney staff found that twos often gave “more sparkle and spirit” even to fast shots, and “in the slower movements gave a smoother appearance to the action.”

But ones were still important. “A scramble action or speed gag, a sharp accent or flurry of activity, the pay-off after a big anticipation, all needed ‘ones,’ ” wrote Thomas and Johnston.3

A core part of the “Disney look” comes from contrasting twos and ones: the thickness of twos for regular movement, the pliability of ones for special cases. It’s not a stretch to say that Disney’s timing style is built on modulation, and the studio could be quite creative with it. Take Pinocchio, where the Blue Fairy moves on twos while her starry gown twinkles on ones — a disparity that helps to give her an ethereal feel.

That said, Disney couldn’t and didn’t lay hold of the full potential of modulation. Its films put their characters in fluid, near-constant motion to keep the illusion of life alive. (We wrote more about this in our issue on Art Babbitt’s “best piece of animation.”) As a result, extremely pushed modulation wasn’t common.

For that, we turn to UPA. Specifically, to the film The Jaywalker (1956) — one of our favorites from the studio, and a cartoon whose movement is one long experiment in timing and contrast.

Many UPA cartoons favor a mix of “twos” and holds — not a ton of modulation. But when the studio used it, the results could be special indeed.

The Jaywalker is a film directed by Bobe Cannon, the maestro of limited animation. He understood better than anyone in his day the art of abstract motion: movements “based on feelings, rather than anatomy,” in the words of Pete Docter.

The book Cartoon Modern notes “the precise manner in which Bobe Cannon would plan the choreography and timing of his animated films,” overseeing it from an early stage. In The Jaywalker, his sense of timing and modulation define the film — it’s almost more timing-centric than it is drawing-centric.

Take the scene up there, where the protagonist Milton runs across the screen in a free modulation between ones, twos, threes and above. By contrast, the cars don’t even have wheel animation — although each vehicle slides steadily down the street, it does so on a single, still drawing. This is an orchestration of time, speed and their contrast.

An even clearer example is the shoe-tying shot later in The Jaywalker, where modulation creates the whole feel of the action:

This moment wouldn’t be the same if you timed it another way or got rid of the modulation. By giving the drawings different durations on screen, Cannon and his animators punctuate Milton’s movement: the “threes,” “fours” and so on contrast subtly with the “twos,” and you feel that change. It feels like he puts more force into some motions than others.

Time it all on twos and you lose the effect. The whole action becomes weaker — faster, but messier and more vague. It’s harder to feel what Milton is doing:

Scenes like these show off the power of modulation — and the way it can define an action even without more drawings.

It’s a trick with unlimited potential, still being explored today (even outside anime). One current animator whose modulation sticks out to us is Jonni Phillips, behind Barber Westchester, Wasteland and more. Phillips’ timing is chaotic and unpredictable — her work contains scenes where modulation happens almost nonstop. She’s called it “frame-rate agnosticism.”

We interviewed Phillips in 2021 but didn’t ask about her use of the technique back then. So, for this issue, we reached out again to see if she could tell us how, when and why she applies it. She explained:

It’s a thing I’ve started to do on an intuitive level but I think working that way allows for a lot more expression with the animation process itself rather than keeping it all to just the drawings. I get pretty excited thinking about ways to make the animation process “nuts and bolts” more expressive and interesting, rather than just the delivery method for drawings or story, and let it work hand in hand with that stuff rather than be just static.

In other words, even basic technical things — things as simple as the duration of a drawing — become a fully free part of the artist’s expression. Take the shot from Barber Westchester below. Even when watching it frame-by-frame, it modulates so much that it’s hard to say which parts are on ones or twos. There’s even a drawing on fours hidden in it. Not to mention the wobbly outlines, which move at their own rate:

These rate changes match the instability of the drawings — everything bends to the intent of the animator. Here’s Phillips on her thinking behind the use of modulation:

I mainly do it for emotional effect — in Barber, the default is 2’s, but I have stuff go on 1’s to emphasize struggling to move something, to emphasize anxiety and other intense emotions, and sometimes I’d put stuff on 3’s or 4’s to communicate weight or a slower movement or to make an action feel more fleshed out and specific.

Again, modulation is a niche and technical thing — all except for the impact it has on you as a viewer. When used well, it’s dynamic and eye-grabbing. It can add surprise and complexity and, in the work of animators like Mitsuo Iso, even realism. It’s a powerful tool with a visceral effect on the audience.

This is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on January 12, 2023. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — now, we’ve made it free to all.

2: Newsbits

Speaking of American animator Jonni Phillips, she’s working on the second season of her Secrets and Lies in a Town of Sinners project. The latest episode premiered today on YouTube. (“Honestly one of the craziest things I’ve made,” she wrote on her Patreon page.)

In America: Cartoon Brew covered the cool-looking My Mu by indie animator Sonnyé Lim (this is also free on YouTube).

Hayao Miyazaki’s film The Boy and the Heron will premiere in America at the New York Film Festival, which runs from September to October.

The series Kizazi Moto hit Disney+ in America (and elsewhere) last month — now, it’s set to air across Africa on TV. That makes it easier for viewers to see in places like Uganda and Kenya, home to key contributors to the show. Disney+ is in North and South Africa as of 2022, but linear TV dominates most of the continent.

In Japan, there’s now a 4K remaster of Perfect Blue. Its premiere screening is set for August 26.

The Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive keeps leading the way in preserving China’s animation history. This week, it’s a rare 1987 eulogy for director A Da.

In Russia, Putin wants to offer full state funding to animation, including feature films. The country’s animation is increasingly being co-opted for propaganda use. At a pitch session this week, one of the animated projects seeking state money caused a stir: Kopeyka, a Cars knockoff whose story is naked war propaganda. The team plans to use Putin and Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu in voice roles.

India’s Studio Eeksaurus (Seen It!) has a new, hand-painted, nearly half-hour film out on YouTube — reportedly two years in the making. It’s about the anti-colonialist writer and philosopher Sri Aurobindo, and it looks stunning (a little like Frédéric Back’s style). See it here.

Lastly, in a rare unlocked Thursday issue of our newsletter, we wrote about the Pippi Longstocking project by Isao Takahata, Hayao Miyazaki and Yoichi Kotabe.

See you again soon!

From Nakamura’s interview in The Portrait Studio Archive, published by E-SAKUGA.

Historian Ma Xiaogua once found modulation as early as Hells Heels (1930), almost certainly not its first use. By the late ‘30s, it was an industry standard in Hollywood.

From page 65 of The Illusion of Life.

Been thinking about this topic a lot recently! I've never understood why Williams was so partial to on-ones, as I'm definitely in the camp that finds the lower framerates more charming (the poses feel more distinct!) In school I was never taught this idea AT ALL (I assumed everything was supposed to be on-twos) but I'm glad to see it's more common than I thought. Will be keeping this article in mind if I ever teach animation someday!

Another great installment! I'm looking forward to watching the new Jonni Phillips animations and of course the North American release of Miyazaki's latest film.