An Introduction to UPA

Plus: animation news

Happy Sunday! We’re back again with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. The agenda goes like this:

1️⃣ Where to start with UPA.

2️⃣ The news in animation, worldwide.

Just finding us? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues right in your email inbox — every week, for free:

With that, let’s go!

1: UPA, a viewing guide

If you were to say that animation hit maturity at Disney in the ‘30s, you’d have a point. The medium’s history does split into pre- and post-Snow White eras. Disney showed the world what was possible.

Animation in the 21st century isn’t much like the retro Disney stuff, though. The whole approach has changed: the variety of styles, the range of stories and tones. It’s like animation speaks a different language than before. Why?

In many ways, it’s down to the impact of one studio: UPA, or United Productions of America. Founded in the ‘40s by disgruntled Disney artists, UPA blew up the medium and reassembled it. To quote historian Giannalberto Bendazzi:

Without exaggeration, it can be inferred that the very idea of animation as an art form, in the United States as well as in other countries, became commonplace with UPA. Entertainment animation left the exclusive realm of comedy and became the foundation for graphic and pictorial research as well as for diverse styles, themes and “genres.” In short, it became a medium for the greatest freedom of expression.1

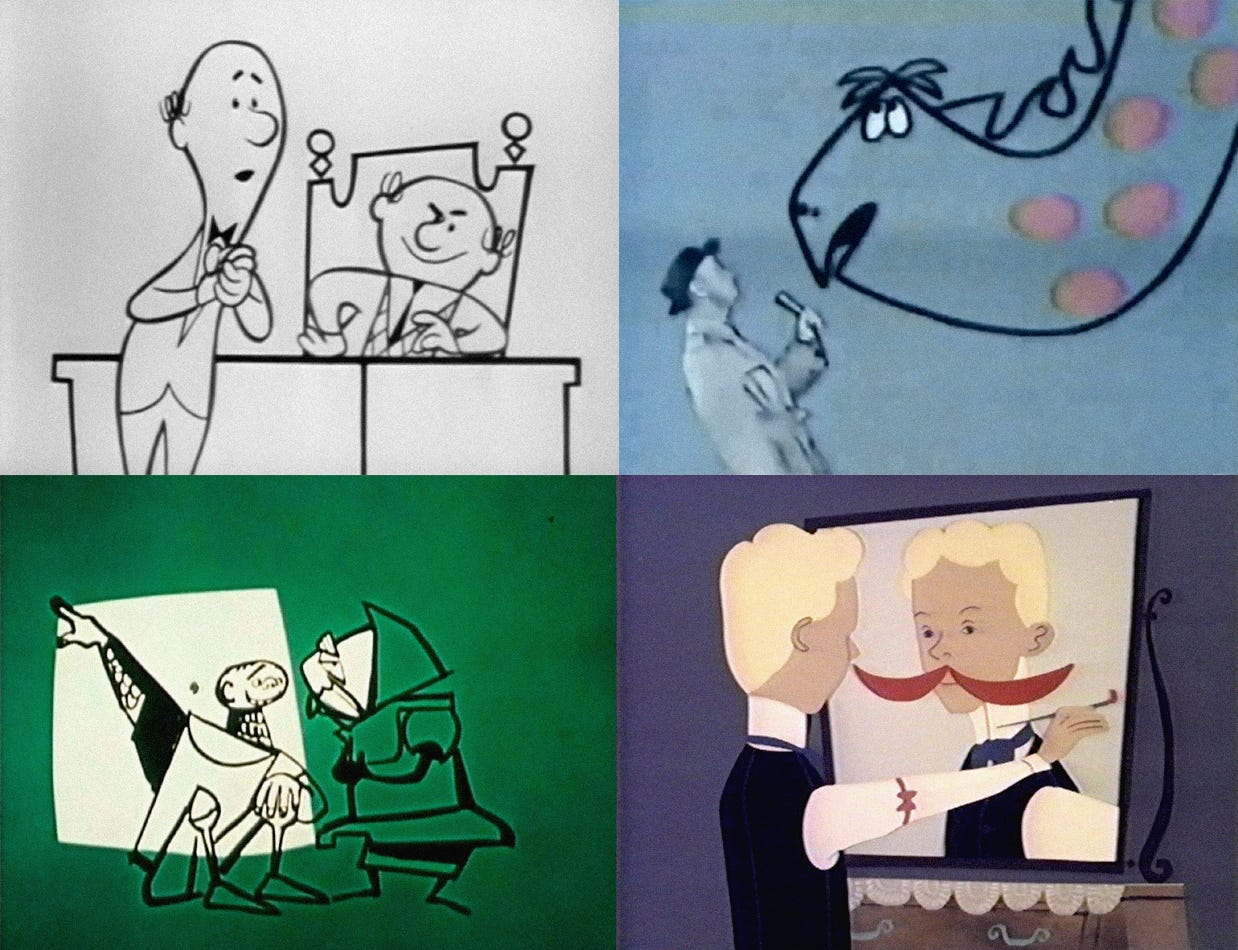

UPA did things differently. It told stories of all kinds — usually starring human characters who face modern-day problems. The visuals draw from modern art and design. The results don’t look or feel like old Disney cartoons.

At the time, UPA won Oscars, rave reviews and the public’s love. Other studios raced to catch up. A few of its films are famous even now — but the studio’s catalog is large and disorganized, and in some cases barely documented. Most of its cartoons from the ‘40s and ‘50s aren’t on streaming services, and many aren’t on DVD. It’s hard now to find the work that people watched then.

So, today, we’re bringing together a range of standout UPA animation with links to watch it on YouTube and the Internet Archive (each title is clickable). Along the way, we offer a little context to explain how and why the studio did what it did. Think of it as an introduction, or reintroduction, to UPA — including the obscure corners of its history.

UPA started innovating soon after it opened in California in 1943. It focused on contract work at first — often military training cartoons.

A Few Quick Facts About Fear (1945) was a “breakthrough” for the young studio, according to historian Adam Abraham. UPA co-founder Zack Schwartz wanted to make a film “that would break away, totally, from everything that had been done before.” It’s Army training in an almost arthouse mode.

Even more important was The Brotherhood of Man (1945), a commissioned film for a union. Its point is antiracism — advocating for, as the script puts it, “An equal start in life. Equal chance for health and medical care, and a good education. An equal chance for a job.” UPA’s staff was progressive; the message suited it. But that message stirred controversy then, like now, and Brotherhood faced accusations of communism.2

Nevertheless, both films were radical steps forward for animation — in design, motion and storytelling. UPA artist John Hubley, a key figure on Brotherhood, penned an article with Schwartz in 1946 about the new era they saw dawning:

We have found that the medium of animation has become a new language. It is no longer the vaudeville world of pigs and bunnies. […] We have found that line, shape, color and symbols in movement can represent the essence of an idea, can express it humorously, with force, with clarity.3

Hubley pushed these theories in Flat Hatting (1946), technically a Navy training film but really a graphic experiment and modern story. It defied its military roots and reached the public. In ‘47, a paper called it and Brotherhood “incontrovertible proof that intelligence and taste are not necessarily at odds with boxoffice principles.”4

These were all impressive films, but they ultimately set the stage for what UPA would do next. After getting a deal in the late ‘40s to make theatrical cartoons, the studio started to nab Oscar nominations. And then it won for Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950).

You could make the case that Gerald McBoing-Boing is the greatest short cartoon from America. Nothing was the same after it. Adam Abraham called it the culmination of “all the ideas and experiments on which UPA’s artists had been working for five years or more.”

To Bendazzi, it was “the epitome of the stylistic gospel that would change again, and forever, the accepted approach to animated films.”

This funny story about an outcast who speaks in sound effects has, Bendazzi argued, “no gags” in the traditional sense. Visually, it uses flat, graphic drawings and a loose-and-abstract kind of color. Its limited animation embraces “a bold, simple conciseness” that rejects the whole Disney playbook on moving characters. Pixar’s Pete Docter said this about the UPA animation style:

Their approach to movement was based on feelings, rather than anatomy — the way you’d feel performing a movement, as opposed to what happens anatomically. Characters would bend in ways that wouldn’t be physically possible, because the artist wanted to capture a certain feeling.5

Gerald came from the gentle, sensitive artist Robert “Bobe” Cannon, who’d directed and mostly animated Brotherhood. He and John Hubley were UPA’s defining forces. Hubley was a director-designer, Cannon a director-animator — and the pioneer of the studio’s new sense of motion. A colleague said that Cannon was “the one who really added that refinement,” that clipped and anti-realistic type of animated gesture.

Hubley followed Gerald with Rooty Toot Toot (1951), another masterpiece. It’s one of UPA’s best-known today, and essential viewing. He did the commissioned film More Than Meets the Eye (1952) as well: a long-form ad that doubles as one of the most unique visual experiments animated in the ‘50s. It has to be seen to be believed.

Less well known, but closely linked to Rooty Toot Toot, are the animated scenes that Hubley directed for The Four Poster (1952). They’re wild and amusing, but occasionally dark and even violent. They were Hubley’s final UPA project — his earlier communist ties got him blacklisted in Hollywood in ‘52.6

Histories of UPA sometimes end there, ignoring the post-Hubley work. But the reality is that much of the studio’s best stuff arrived after Hubley left, as new artists joined and everyone’s talents continued to develop.

See Ted Parmelee’s Tell-Tale Heart (1953), a fully serious horror film based on Poe’s story and done all in surreal paintings. It’s a favorite of Guillermo del Toro’s. Unicorn in the Garden (1953) by Bill Hurtz puts New Yorker drawings in motion to tell a witty, cynical modern fable — Hubley himself called it “excellent.”7 Cannon’s Madeline (1952) is movement-as-poetry.

There’s also the question of UPA’s big hit: the Mr. Magoo series. Hubley co-created the character and directed the first entry, The Ragtime Bear (1949). The series kept going even after Hubley lost his job — and some of its best films were made without his involvement.

It’s a little tricky to explain the appeal of Mr. Magoo to current audiences — the joke behind him is specific to his time. Magoo was, in the words of historian John Culhane, “the classic ‘50s reactionary.” Hubley called him a “thickheaded conservative.”8 As we wrote last year:

In his best films, Magoo is like a Don Quixote for the Cold War era. He sees exactly and only what he wants to see — his near-sightedness is an expression of his own inner myopia. Magoo’s world is a delusional swirl of the fun he dreams of having, the archaic things he remembers and the imaginary threats and inconveniences that test him everywhere he turns. As these delusions meet reality, chaos ensues.

Magoo won UPA’s second Oscar with When Magoo Flew (1954), directed by Pete Burness. Although the character is still trapped in his own fevered imagination, he looks different from the Magoo that Hubley invented for The Ragtime Bear. This is thanks to the influence of Sterling Sturtevant.

Sturtevant was a prominent designer at UPA during the mid-1950s, described by one director as an “incredible draftsman.” She designed The Fifty-First Dragon (1954) and remade Magoo into his recognizable form. Sturtevant had a hand in several of the best Magoo films, too — When Magoo Flew, Magoo Express (1955) and more. Even after she left UPA, her additions to the Magoo visual canon remained, helping to turn cartoons like Magoo Makes News (1955) into some of his finest.

Magoo films weren’t the only highlights of this mid-1950s period. The unusual Baby Boogie (1955) by Paul Julian, the painter of The Tell-Tale Heart, is a boogie-woogie journey through a child’s imagination — rendered in doodle characters and Matisse-like cut paper. Cannon directed How Now Boing Boing (1954), a worthy sequel to Gerald that doesn’t get the attention it deserves.

Then Cannon did The Jaywalker (1956), an Oscar nominee about a man pathologically hooked on jaywalking. It’s one of the UPA greats, and an example of the kind of cartoon that the studio made possible: bold minimalist design, a story about a human in modern times, movement that shatters Disney’s principles of animation.

No survey of UPA is complete without a mention of its work in early television. A good deal of UPA’s money came from TV ads made at its New York branch. Its cartoon commercials had, by the mid-1950s, bigger audiences than animation in theaters. And none were more acclaimed than UPA’s Bert and Harry Piel.

The Piel brothers were household-name-famous in the East Coast areas where their ads ran. These were anti-commercials, starring two salesmen who were entertaining to watch but purposely bad at their jobs. Around 1955, spots like Bert’s Offenses (and this unnamed one) delivered theater-quality cartoons to TV audiences. The ads were so popular that Piel began to publish their airtimes in magazines and newspapers.9

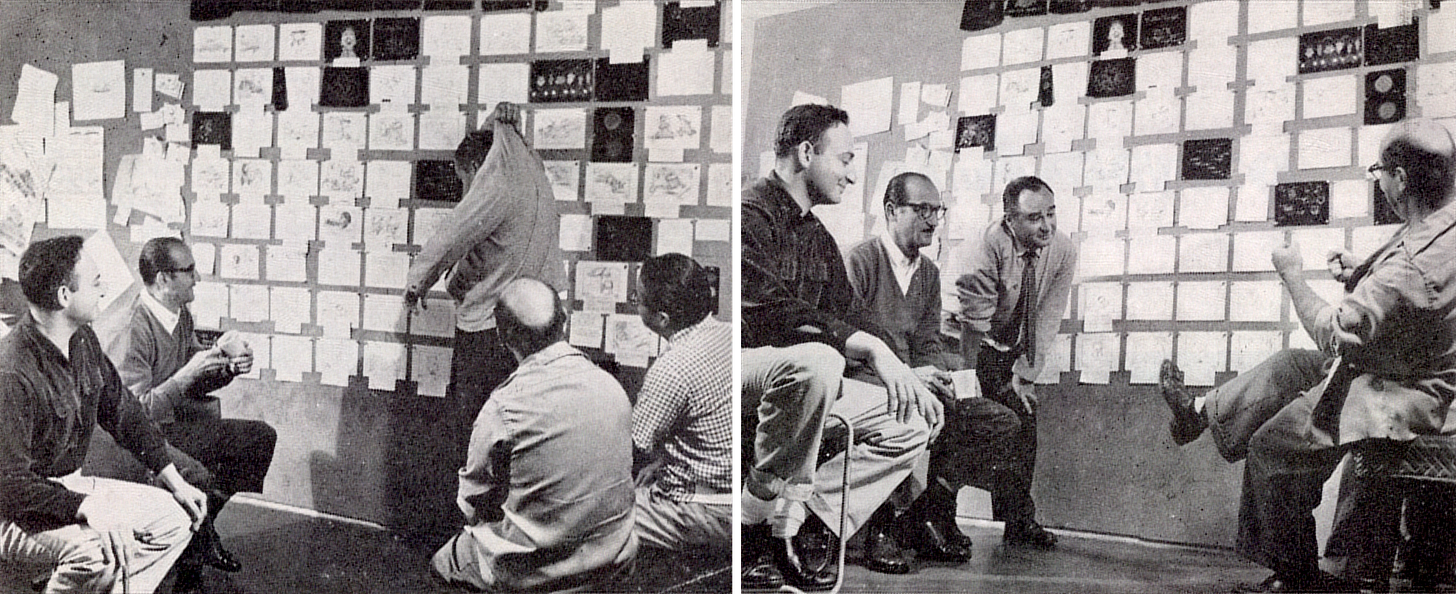

Then you have The Boing-Boing Show (1956–1958), a TV series that stands as the strangest and most unhinged creation in UPA’s history. Cannon supervised it, overseeing teams of younger artists and new hires.10 It’s a deeply uncommercial anthology of animated shorts with varying tones, styles and lengths.

Take The Sleuth’s Apprentice: The Lost Duchess by Rod Scribner. It’s a vicious satire of detective stories, and the animation is unorthodox even by UPA’s standards, paying little mind to design consistency and at times jittering with nervous energy. Quiet Town by George Dunning (Yellow Submarine) and Outlaws send up the Western genre — the former is indescribable, and features explicitly violent lyrics.

Meanwhile, We Saw Sea Serpents looks like a ‘90s MTV cartoon. Photos of real people are cut out and animated in ridiculous ways — the TV viewing audience shows up as bug-eyed drones on the couch. Yet the story is something else: it mocks Columbus, and it’s about how sea monsters (aware that they don’t actually exist) make a plan to survive the Age of Discovery by hiding “deep in the minds of men.” They choose to become the Other, “foreigners,” that people imagine when they imagine each other.

It’s hard to picture cartoons like these (or The Invisible Mustache of Raoul Dufy, or The Day of the Fox) airing on TV in the ‘50s, or really any time. The Boing-Boing Show was a ratings flop, and not without reason. It’s a mishmash: duds beside classics, shorts for young children beside adult comedies, simplistic films beside incredibly complex ones.

But it’s hard to complain too much. At its best, The Boing-Boing Show exemplifies what made UPA UPA: the unbridled creativity, the push for the new and the willingness to upend the whole animation medium to get where it was trying to go.

2: Newsbits

We lost Jim Korkis (72), a prominent animation historian.

American animator Ian Worthington released a new episode of Bigtop Burger, wrapping up its second season.

A Japanese poll asked whether people minded which studio made the anime they watched. Almost 37% replied that they didn’t watch anime at all, and over 36% who did watch didn’t pay attention to studio credits. Among the small minority of viewers who focused on studios, Kyoto Animation was the top pick.

Also in Japan, there’s a teaser for Urahara — a 3D project that resembles a retro, pixelated PSX game.

The Estonian film Sierra, one of the best animated shorts of 2022, is now online.

One more from Japan: Hayao Miyazaki’s Boy and the Heron earned over 4.6 billion yen (around $32 million) after 17 days in theaters. Despite a record-breaking premiere, it’s on track to roughly match the box office of The Wind Rises.

A film from France’s Gobelins, Thaba Ye, has won a BAFTA. It’s a fantastical story set in South Africa (co-director Mogau Kekana is from Johannesburg).

In China, Chang’an continues to boom. It’s now passed Jiang Ziya to become the second-biggest Chinese animated film, behind Nezha. Maoyan currently has its box office above 1.65 billion yuan (around $231 million).

The American Lackadaisy animation project is crowdfunding its first season to huge success.

In Ukraine, Yevgeny Sivokon received a lifetime award from the film academy for his contributions to Ukrainian cinema. He’s known for Soviet-era animation like Laziness (1979), about a man being replaced by his own pet fish.

Nigeria’s Nollywood Reporter did a long interview with Ebele Okoye (Love Marks). She moved to Germany in 2000 to pursue animation, and she talks about her life, career and efforts to train Nigerian animators.

Lastly, we wrote about the creation of the Soviet cartoon The Story of a Crime (1962). We’ve thought about covering it for as long as the newsletter has existed, and we’re thrilled to have done it after all this time.

From the opening sections on UPA and Gerald in Animation: A World History (Volume 2), cited several times. The quotes from Adam Abraham all come from his book When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA — a main source throughout.

The Brotherhood of Man adapts an antiracist pamphlet called The Races of Mankind, used in the Army until it was banned in 1944. Hubley said that the Army “bought something like 300 prints” of the film version, but it was banned as well when “some Southern congressman started to squawk.” UPA’s Brotherhood later appeared in a 1948 government report on communism, where it’s linked to various communist suspects.

See Animation Learns a New Language in Hollywood Quarterly (July 1946).

From the Los Angeles Daily News (October 2, 1947). See also Hubley’s 1947 correspondence with the San Francisco Museum of Art, which screened Flat Hatting.

From this article in the Los Angeles Times. The quote about the “refinement” of Cannon’s animation comes from Jules Engel in this interview.

Hubley confirmed to Sight and Sound that The Four Poster was his final UPA project.

On Twitter, del Toro gave The Tell-Tale Heart a rating of “A+++.” Hubley’s praise for The Unicorn in the Garden is from his interview in The American Animated Cartoon.

The comments from Culhane and Hubley about Magoo come from Walt’s People (Volume 11). The “incredible draftsman” line was Bill Hurtz, quoted in Cartoon Modern.

We wrote about the full story of Bert and Harry Piel last year.

Cannon said that his role on The Boing-Boing Show was “getting out of the way of the guys who do the work,” according to The Reporter Dispatch (January 15, 1957).

Thank you for this! I knew some of these like Gerald and Magoo, but didn't link them together. Thanks for the links, I have great things to watch now....

Those UPA backgrounds are so distinguished.