Happy Sunday! Glad you could join us for a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our slate today:

1) Tissa David’s world-class performance.

2) Newsbits in world animation.

Before we get started, we want to welcome our new subscribers from Substack Reads! The awesome Coleen Baik (of

) curated the latest one, and she was extremely kind toward our newsletter. To quote:The content may seem niche at a glance, but really, it’s not just for animation folks. It’s incredibly well-researched and full of fascinating history, thoughtful criticism, and little-known tidbits. It comes into the inbox like clockwork. It’s also quite accessible! I’ve discovered many gems through this publication.

Our thanks to Coleen for this wonderful shout-out. With that, let’s go!

1 – “I love her!”

Not every animated film works. Sometimes, a project stumbles because of planning or team coordination problems — or trouble with budget, with schedule. An artist’s reach may exceed their grasp. An idea may sound better than it looks. Higher-ups may insert themselves into a process they don’t understand.

Sometimes, all of these things happen at once and create a mess.

But a mess can be interesting. And some messes are brilliant — at least occasionally, in parts, on purpose or not. Those are worth examining. You may uncover something great that only chaos could’ve allowed.

The film Raggedy Ann & Andy (1977) is one such mess. Today, it has a cult following. It inspired The Amazing Digital Circus, maybe the biggest animated series right now.1 But Raggedy Ann is awkward, even bizarre — from its story to its stage direction to many of its songs. And it was a production nightmare, mostly disowned by its team.

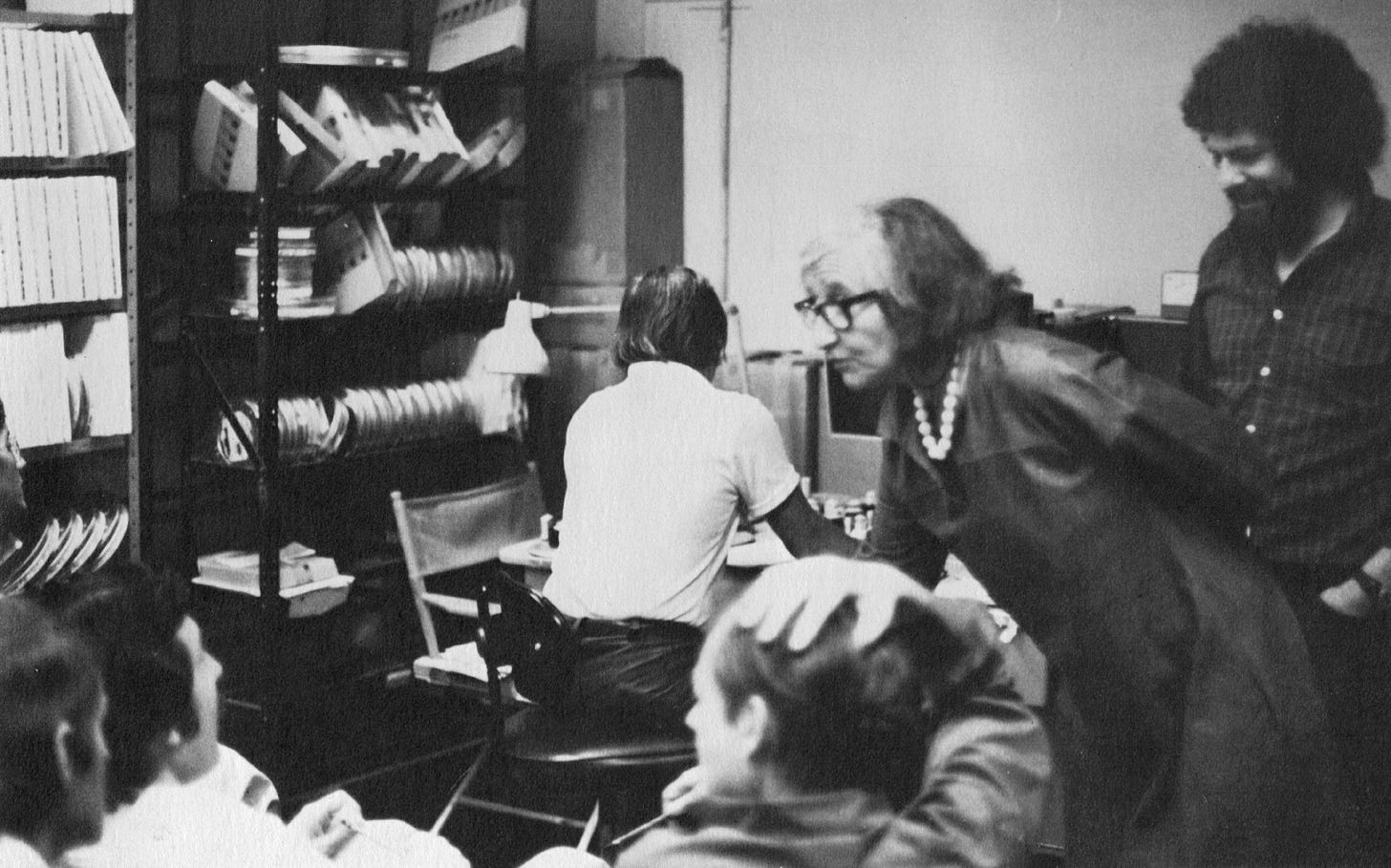

That included director Richard Williams, later the animator behind Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). He went into this project with ambitions: to get a Disney-level movie, staffed by the industry’s best, out of the Raggedy Ann license. Williams faced lots of meddling, and he got distracted — endlessly reworking his team’s animation himself. He couldn’t keep the schedule. His budget ballooned.

Finally, someone else took over, and he wrote the film off. “I had virtually no control over [it],” he said.2

Before that, though, Williams had hired some of the best — and he’d pushed them. Two of the animators were veterans from Snow White; another was a Looney Tunes ace. And the lead animator, Tissa David, was one of the greatest to hold a pencil.

She wasn’t happy with Raggedy Ann, either. As David said in 1978, the film:

… unfortunately failed. There were many reasons for this. Namely, the creative intent to turn a typical Broadway musical into a cartoon proved unsuccessful. Making matters worse, the film became a family business: the producer’s daughter wrote the screenplay, which didn’t benefit the work. And the leadership was taken over by the composer, who gave too much of a role to his own songs. Lastly, 11 three-minute songs in a seventy-minute film is a little too much. That is to say, there was not enough time left for good animation. All of this together resulted in the work of [John] Kimball, Art Babbitt, Richard Williams and myself regrettably going to waste.3

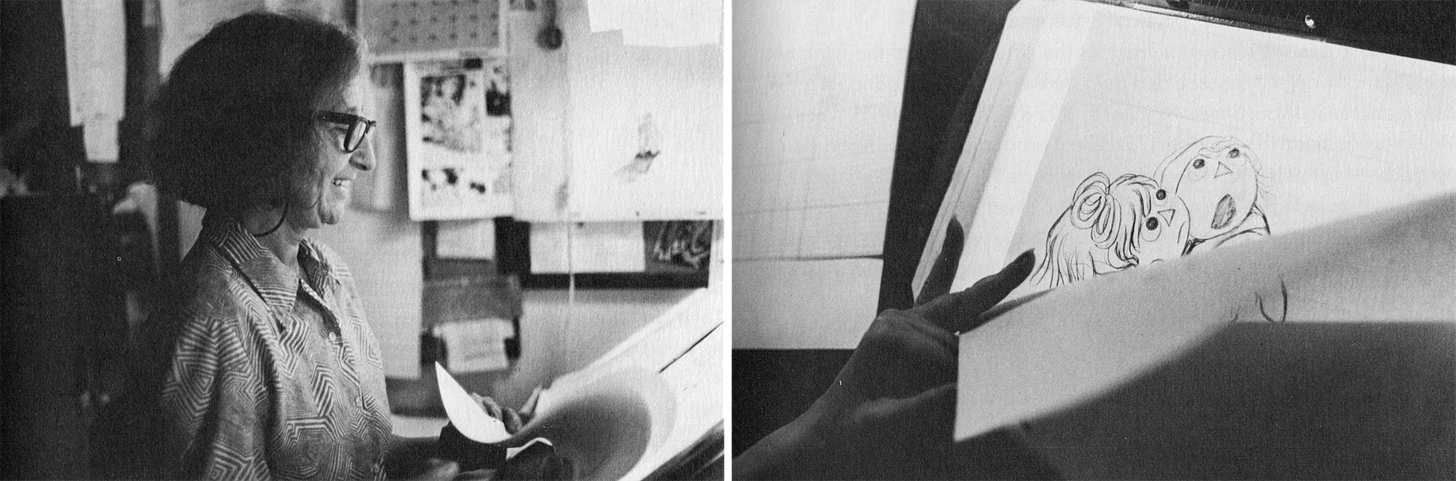

Yet David had put care and heart into her work. She animated Raggedy Ann in key sections of the film — bringing a fully unique style to the character. “I love her!” David said during production.4

She aimed to do something special. The result, in the middle of this strange movie, is one of David’s finest and most-respected turns as an animator.

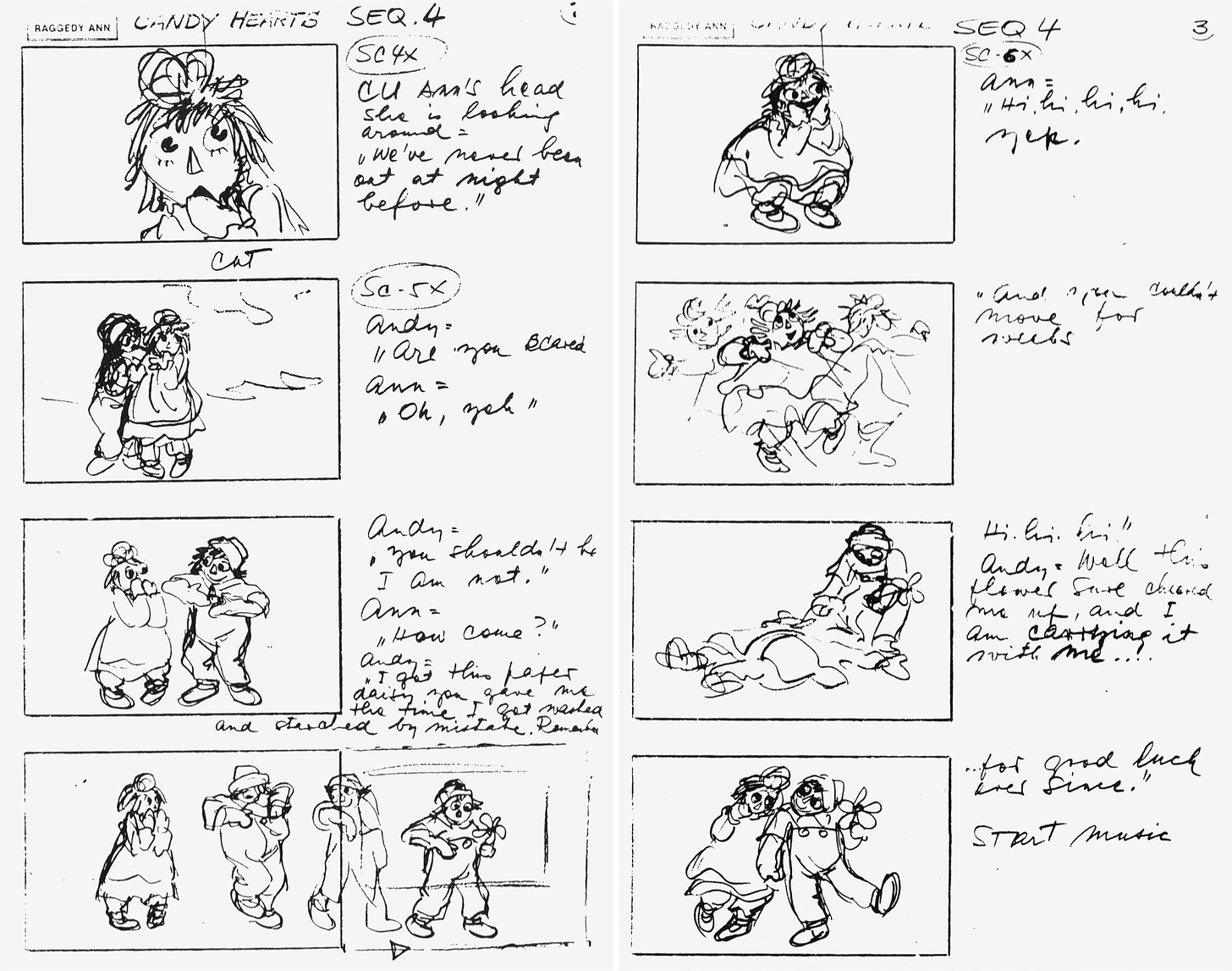

To call Tissa David this film’s lead animator is no exaggeration. She drew “over 1,000 feet, the most footage of any[one],” according to historian John Canemaker. At the center of her work was a sprawling, seven-minute solo sequence of Raggedy Ann and Andy in the woods. It was the first sequence done, and a template for the others.

As a team member put it, “The rest of the film was built on the back of this one.”5

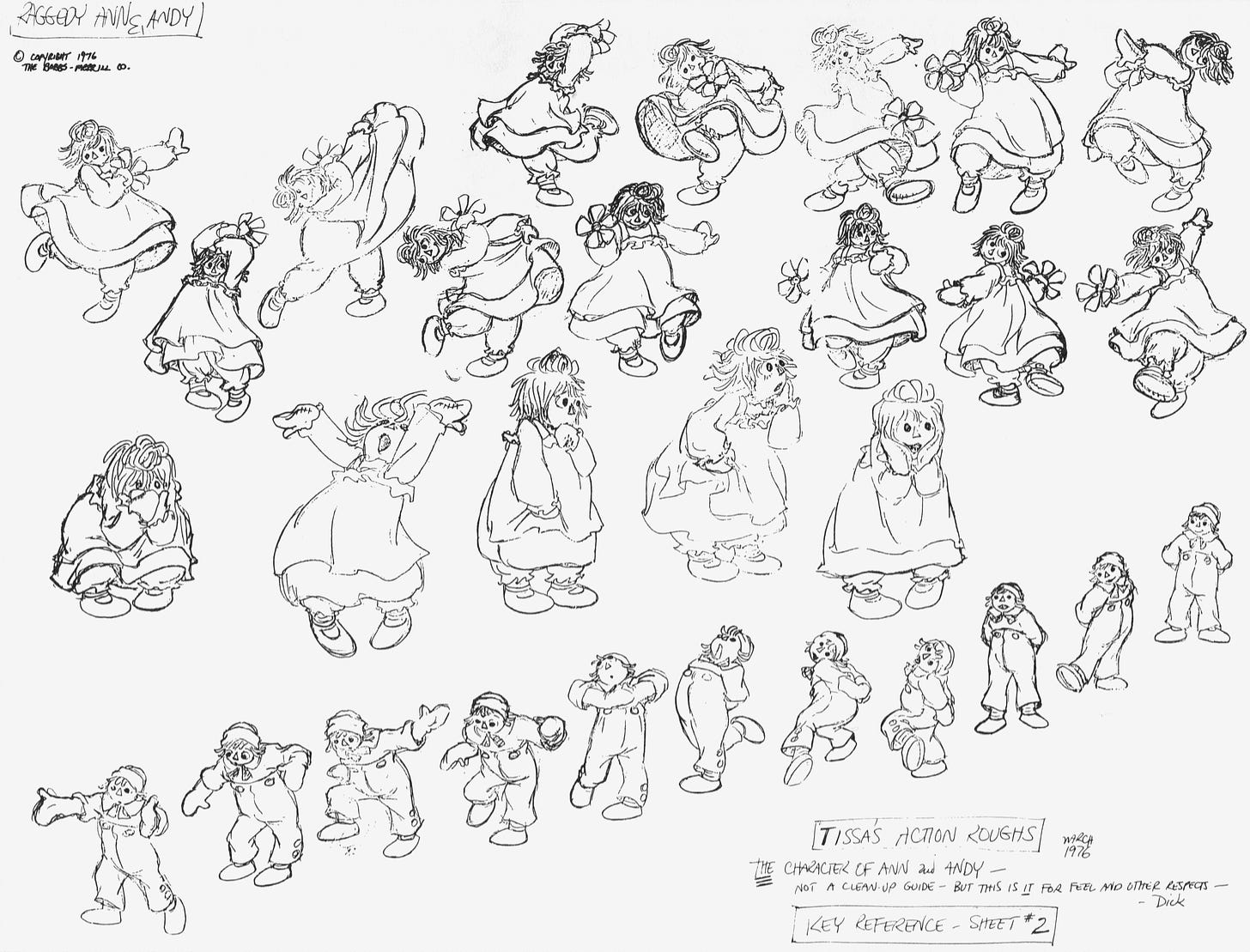

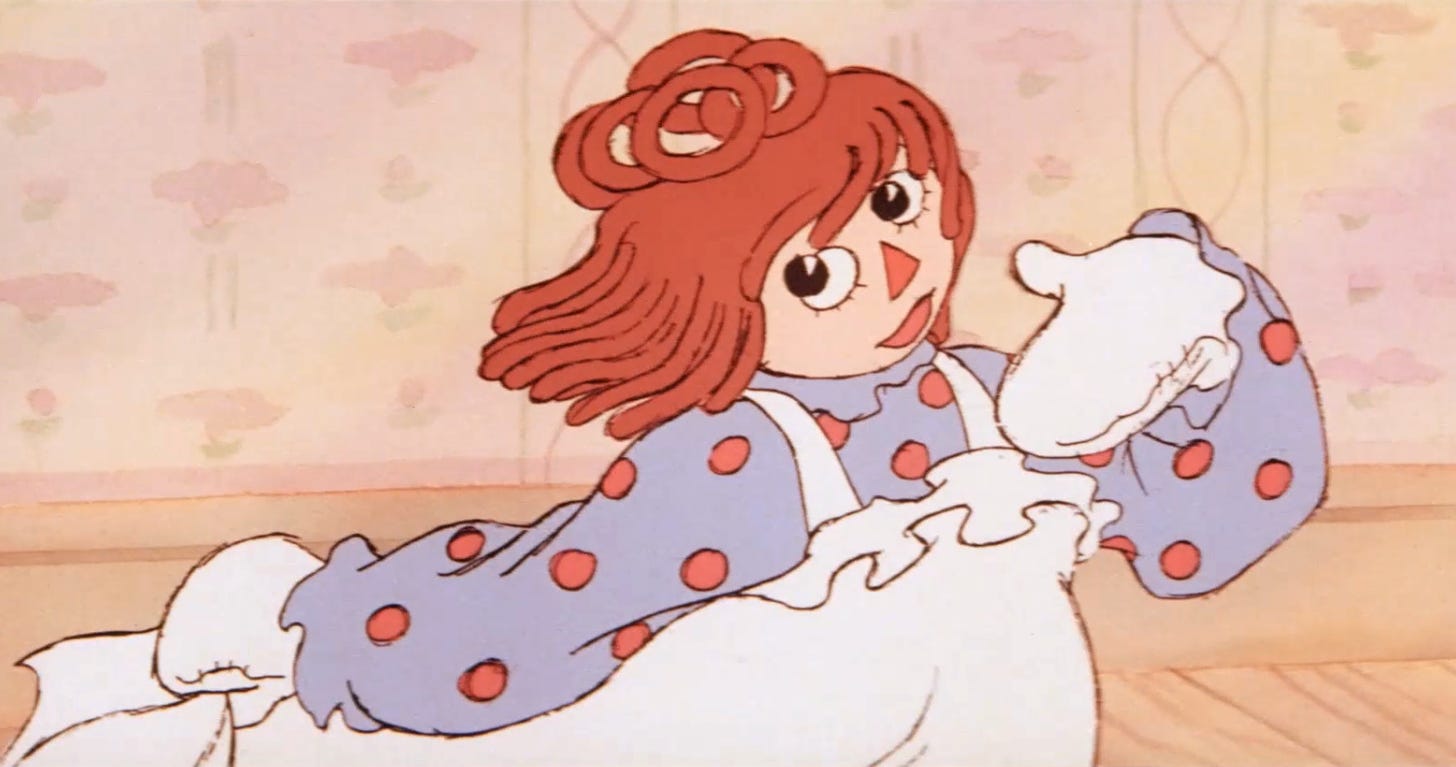

And, in terms of David’s animation, the sequence is beautiful. Raggedy Ann is both lumpy and graceful, a mass of draping cloth. When she dances or spins or flops to the ground, it doesn’t feel like you’re watching a human being. She and Andy are dolls, and they act like it — boneless and light. But they also feel like living beings with personalities.

“I think you do have to love her [to animate her well],” David said. “Not as a little cartoon character but as Raggedy Ann. It’s like a little thing that is alive. I think that’s very important.”

Her goal was to find Raggedy Ann’s soul and show it with movement. David got to it through the voice — as she did on most projects. “I listen to the voice [track] over and over and over from morning to night,” she noted. “Ann’s voice tells me who she is.” She established a character that’s “very gentle,” “very trustful” and “like a little animal that goes purely by her emotion, intuition, instinct.”

This character is also wholly fresh, down to the way she pushes her hair out of her eyes. David used no cliches in her motion: none of the tired shorthand that can drain a scene’s life and bring a different character to mind — or a dozen different characters. (“The cliches always work,” she once told an animation class, “but I don’t want any of you animating cliches.”)6

Richard Williams hoped to keep the cliche count to zero. He’d pulled David onto Raggedy Ann & Andy early, and she’d helped to set the designs and movement of the leads from the start. She “basically created the ‘look’ of the Ann and Andy characters,” in the words of Eric Goldberg (her assistant on this film and, today, Disney’s main 2D animator).7 He explained:

... Tissa David gave the title characters certain rules: no blinks because their eyes are sewn-on buttons, and no tongue or teeth in dialogue, since they were cloth dolls with cloth faces. As her assistant animator, I learned for the first time how to manipulate mouth shapes alone for convincing lip sync.8

David’s work on the Raggedy Ann character, not just in the woods sequence but throughout the film, is a refined form of what she already did well. She’d developed a style of movement and timing different from anyone else’s.

In her native Hungary, David had learned animation after being wowed by Snow White (1937) in her teens. She got hired to a local studio — a colleague remembered her as “exceptionally talented even then.” Bombarded by World War II and the post-war regime, she fled to Paris. There, David kept animating and saw the cartoons of UPA, which became wildly popular. As she said:

I decided in Paris that I want[ed] to work at UPA because that’s the only studio that really interested me. ... [W]hen they came out, it was like a bomb. I mean, it was like an explosion. It was something extraordinary.9

“Simplicity” and “gentleness” were words she used for these cartoons. They weren’t “over-animated,” either — the label she applied to Disney, which she mostly disliked. When David finally joined UPA in New York during the ‘50s, she became the assistant to Grim Natwick. He’d come from Disney’s Snow White himself, but had since adapted to modern cartoons (“new, fresh, lively, lovable,” he called them).10

David was very experienced by then — but she still absorbed everything Natwick said. And her mature style began to form. “[E]ven today,” she admitted in 1975, “I don’t do one line without something in my brain Grim told me.”

The kind of animation David invented was a blend — of Disney, of her work in Europe, of the principles of limited animation. Her Raggedy Ann is too complex and three-dimensional to be UPA, but not broad enough to be Disney. The character is both precise and fully animated. And, again, alive. Writing about the film, John Canemaker pointed to “the feeling of warmth that Tissa’s animation conveys, an almost tactile sensation.”

Richard Williams told the Raggedy Ann team at one meeting that he wanted “real charm without its being Disney.” David replied, “Don’t worry. I can’t animate Disney charm. I will do my own.”

Her technique was partly off the cuff: planning scenes, then deviating. She always animated “straight ahead,” meaning one frame after another. Most animation begins with a handful of key frames, to establish the start and center and end of an action, but not hers. “I am a very intuitive animator — I never know when I sit down to work what will happen,” she said. When it came to this film:

I have the whole sequence posed out [in sketches] so I know the general direction I go toward. As I go along, it changes. I work rough first, in black pencil. I put it down so black it takes me a terrible time to erase if something is wrong!

Her one-of-a-kind sense of timing helped her make it work. It was part of her. When she taught animation, she cautioned her students against using stopwatches for most jobs — the typical method of that era. Instead, they needed to build intuitive timing: she recommended a metronome.

When Raggedy Ann moves, even when she’s not dancing, all of her actions are structured with rhythm. That was core to the Tissa David style. In one of her classes, a student wrote in his notes as she spoke, “Every action is more or less dancing; has certain rhythms.”11

David had built this style over a lifetime. She was already in her 50s when she animated Raggedy Ann (she lived to be 91), and she was fully aware of her own likes and dislikes. While she was generous and understanding in her personal life, she was lethal about animation. Someone who’d gotten to know David outside of work was shocked, when animation eventually came up, to find her “getting judgmental, which I’d never seen her do before.”12

Fantasia? “Horrible.” The Jungle Book? “Dreadful.” She once told her class, “Disney is always tasteless... but pleasant to look at.” To one student, she was more specific:

If you think Aladdin is character animation, I’ve got news for you. It isn’t.13

When she taught, she would tear a student’s work down and build it back up in moments.14 David was critical of any animation she found lacking — very much including her own. But those deep feelings ran both ways. She loved things and people. She praised Spirited Away, Tale of Tales (1979), the Brothers Quay, Caroline Leaf’s The Street. Students she criticized could become her friends, even her collaborators. Plenty of them did.

“I learned so much working on her work that it was … really an eye-opener for me,” said Eric Goldberg of his time on this film. It’s worth noting that he’s famous today for Aladdin. But David had praise for Goldberg, too: she loved his Raggedy Ann drawings. “Eric is the only one who can clean up my Annies,” she said mid-production.

David loved the Raggedy Ann character, too — and her job on this film, and collaborating with Richard Williams.15 She didn’t love the end product. Most of the industry seemed to share that opinion. Even so, the parts she drew, these floppy-graceful and wide-eyed dancing things, shine amid the mess.

2 – Newsbits

We lost James Earl Jones (93) — the great actor known for voicing Mufasa in The Lion King, among many other roles.

In India, Vaibhav More Films won an award for a mesmerizing Coca-Cola ad it released last year. Check it out on YouTube.

According to a new report, the film To Be Sisters was France’s most-exported short of 2023. It has a lovely, hand-drawn feel — see the trailer here.

Pixelatl wrapped up in Mexico, and the list of winners is out. Included are Tapir Memories (Colombia), Miedo (Mexico) and Wander to Wonder (Belgium).

The Linoleum animation festival in Ukraine is over, too, with the top award going to I Died in Irpen (trailer).

After a successful run at festivals, the American film American Sikh (2023) is out on YouTube. Definitely worth the time.

Lucky Dog, a short from India we enjoyed a lot this year, will be traveling abroad via the Busan Film Festival in Korea — a big one.

In Thailand, a local animated feature called Out of the Nest is doing well at the box office. Co-produced in China, and reportedly budgeted at more than $18 million, it’s had a record-breaking opening for Thai animation.

South Korea has a local hit as well: Heartsping. It’s earned more than $6.7 million and become one of the country’s three most successful animated features ever.

In Russia, the problem of pirated movies in theaters is growing serious — for “nine out of [the past] 13 weekends,” the box office has been ruled by bootlegs. Two of the largest? Inside Out 2 and the latest Despicable Me, which haven’t been officially released due to the ongoing sanctions and boycotts.

Lastly, we wrote about idolizing key animation to the detriment of other roles, and what can happen as a result.

Until next time!

There are too many parallels between Digital Circus and Raggedy Ann to count — its creator has joked about her obsession with the film.

From Funnyworld #19 (here). For details about Williams’ management of the film, budget trouble and eventual replacement, see the book Cartoon Capers, plus Filmmakers Newsletter (September 1977) and Michael Sporn’s blog (here and here).

Quoted in John Canemaker’s book The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy, our primary source for the issue, and for many other quotes today.

From New Jersey’s Courier-Post (April 9, 1977).

From Goldberg’s book Character Animation Crash Course.

The colleague was Dezső Macskássy, as quoted in Tissa David’s section of the Eszter Dizseri book And Yet It Moves (És mégis mozog). David’s words come from this interview. For the other biographical details, see here.

David’s quotes about UPA and Disney come from this article. For the Natwick quote, see Cartoonist Profiles (March 1977).

See this article. It’s worth mentioning that, when Hungarian director Marcell Jankovics previewed his film Johnny Corncob (1973) at Annecy, people were impressed. “A critical remark was made by Tissa David alone,” he wrote in Közhírré Tétetik.

Mr. Warburton (Codename: Kids Next Door) was one of David’s pupils, and he gave a memorable account of her critiques.

This is so perfectly timed! I was watching David's NYU talk twice this week and getting lost in the class notes from her workshops on Sporn's blog -- thank you for packing this issue with meticulous sources so I can continue my own research into her work

"Kozhirre Tetetik" seems like such a goldmine that, even as a Hungarian, I was not aware of

Thanks again by heart

Fantastic article! I regret I knew very little about Tissa David's work, and I'm grateful to have that remedied, and also to learn a little bit more about Raggedy Ann as well. I really appreciate all the different sources you're able to draw on and tie together into a story, and the thoughtful analysis of how she animated the character.