Welcome! It’s time for a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our plan today:

1) About Flow — and how Europe makes animation.

2) A new Irish short.

3) The week’s newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1 – Making the movies Hollywood won’t

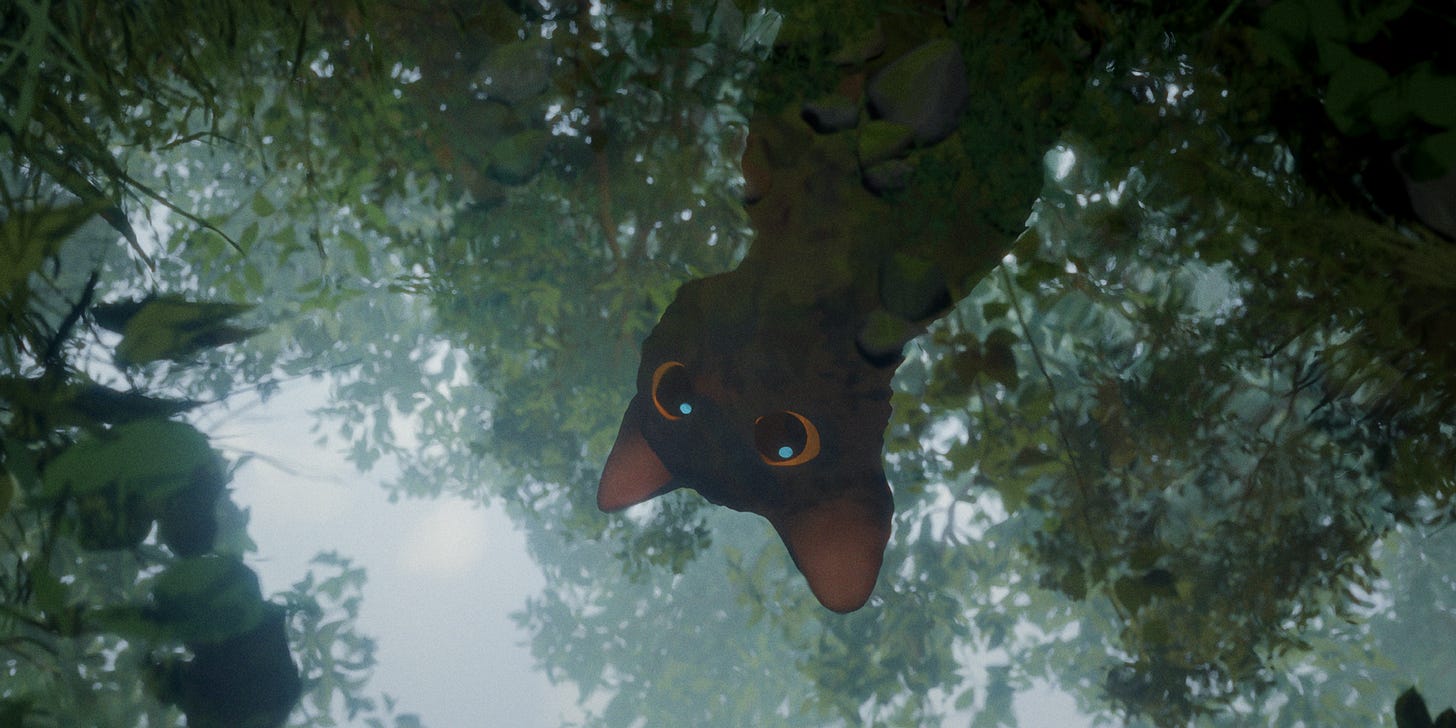

Flow won. Tonight, it took the Oscar in the animated feature category. This little film from Latvia — a film with no words, made with free software and $3.7 million — came out ahead of two Hollywood hits.

Director Gints Zilbalodis is only 30. He cut his teeth on an hour-long movie he created by himself: Away (2019). That got him noticed, which led here, to Latvia’s first Oscar.

Still, the victory doesn’t belong just to Latvia. Zilbalodis and his team defined and oversaw Flow there, but it was animated by studios in France and Belgium. It was a European co-production — like most full-length animation from the continent. This is the first such animated feature to claim the Oscar.1

Hollywood loves Flow. It’s been praised by Guillermo del Toro; Barry Jenkins called it a “masterpiece.” Yet it couldn’t have been done in Hollywood — it’s too odd for the people who call the shots. This is a movie with no stated story, about animals that don’t talk, filmed in long, immersive takes that can last for minutes. Plus, it’s indifferent to the visual fidelity race: certain execs might dismiss it as previz.

Flow succeeded anyway. It earned $20 million — far more than it cost — and swept awards season. This comes as Hollywood animation is reeling from executive mismanagement: cutbacks, canceled movies, poor treatment of artists and a chronic aversion to risk. Today, only a few animated films are happening there at all.

“Animation is performing better than ever, but Hollywood studios are asleep at the wheel,” Cartoon Brew argued last month. “Their theatrical schedules are barren at a time when they should be brimming.”

You can’t say the same about Europe. Its co-production model is only getting stronger, more daring and more popular. Flow’s success, and now its Oscar win, proves it.

If you’ve seen Flow, you’ve seen the train of logos at the front. They run for a couple of minutes. We find names like Arte, RTBF, Eurimages — around 20 of them.

Those are traces of Europe’s co-production system at work.

It’s a network — partly an informal one. Its navigators are people who know people. All across Europe, there are parties interested in helping films happen. A local government might offer money, or rebates, or tax incentives. A broadcaster might buy airing rights ahead of time. And so on.

Each bit of funding is small: the risk is spread around, diluted. Put enough of this stuff together, though, and you get the budget for a feature. In the case of Flow, Arte and RTBF are both broadcasters; Eurimages is a film fund. The other logos belong to other financers, and to the many production houses and distributors involved.

This is not a sexy system. It’s built on dry phone calls, meetings, pitches and handshakes. Hollywood tales of soaring success and explosive failure aren’t common. But it’s given us special films like Ernest & Celestine, The Secret of Kells, Flee, The Summit of the Gods and Robot Dreams. All but one of those was an Oscar nominee. Now, Zilbalodis and his team have taken it all the way.

Some years back, the Pixar vet who co-created Ratatouille’s story, Jim Capobianco, left Hollywood to direct a co-production in Europe. It was The Inventor (2023), a charming piece. We once asked him about the switch. He said:

In the European system, the director has a lot of control, whereas in the Hollywood system the producer has more control. So, once we got going, I pretty much had complete creative control. …

The budgets are smaller than in Hollywood because of the tax breaks and government funds you can tap into. … There can be many entities to keep in touch with, figuring out what work and what percentage of the film will go to which co-producing country. Because that’s how you get funds; part of the film needs to be made in that country. … It’s a lot to juggle for the producers.

Capobianco couldn’t sell The Inventor in Hollywood: it was too idiosyncratic. It’s a musical about Leonardo da Vinci, told through a mix of stop motion and 2D. But he got it done with Europe’s co-production model — the same model that allowed Zilbalodis to make his wordless animal movie.

There was a time, back in the ‘90s, when European animated features weren’t common. The infrastructure in place now was looser then.

Didier Brunner was one of its foundation-layers. As the producer of Michel Ocelot’s Kirikou and the Sorceress (1998), he showed what could be. That film is obscure in the States but iconic in France — and held in high regard by the late Isao Takahata.

Brunner called it “extremely difficult” to gather money for Kirikou. Most of it came from public funds, and so the production was divided around Europe — Latvia, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Hungary. Each country involved brought the chance for grants and other help, but these were somewhat uncharted waters. “Michel spent all his time in planes and on the phone,” Brunner said. “It was an extremely physical task for him.”

When Kirikou became a surprise hit, though, it made things possible. People spoke of the “Kirikou effect.”

Brunner was there as European animated features grew. He and his company Les Armateurs shepherded co-productions like The Triplets of Belleville (2003), Ernest & Celestine and The Secret of Kells. That third film, he said, was an example of what Les Armateurs looked for: “an auteur project with all the production risks that entails, a script that was not formulaic, original graphics and a 2D film.”2

Like he noted elsewhere:

... the uniqueness of European animation studios, and especially French ones, is the strong particularity of each film, which has its own graphic universe. This French and European uniqueness is a wealth that must absolutely be protected, because it is this which will differentiate [us] from “Hollywood” animated cinema.3

The uniqueness Brunner described is now the standard for European animation — even outside his own projects. It doesn’t come easily: a co-produced film takes years to move from idea to reality. The hunt for partners and deals takes up most of those years.

Flow itself was a half-decade process. “At first it was just me developing the story and with the producers looking for funding. Gradually we were building the team,” Zilbalodis wrote. “The production was actually quite fast — less than a year.”

The co-production system is richer and more efficient than it was in the ‘90s and ‘00s, though. People know this road — many animation producers have walked in Brunner’s footsteps. One of them is Ron Dyens, involved in films like Long Way North (2015) and Marona’s Fantastic Tale (2019). On Flow, you find his name again.

“My job is to stay attuned to talent wherever it may be, and when I saw Gints Zilbadolis’s first film, I knew immediately that this guy was really talented,” Dyens said in January. “I was captivated by the story, the hypnosis, rhythm and vibration. A film is all about vibrations. I absolutely wanted to work with him, and I guess I was right.”

People sometimes ask what happened to fresh and exciting animated films, or to classic 2D features. In many cases, the answer is simple: they went to Europe.

The European public doesn’t necessarily demand animation like this. Often, co-productions are only modest successes, if not flops. But the infrastructure is there, the financial risks are minimal and the producers are looking for artists with ideas. And so the films get made, whether they’re in wide demand or not.

Beautiful, different animation like Flow is the result. Zilbalodis’s project was tiny — despite those 20 logos, its budget wasn’t even a rounding error for Hollywood. “[I]n these kind of productions,” he recently said, “I think we have more creative freedom to take bigger swings and try things that may not have really been proven.”

The film’s Oscar win shows that Zilbalodis and his team are on to something. It also shows, maybe more than ever, that the system works. The Academy has admired European animation for years. Now, it’s admitted that Europe has something Hollywood doesn’t.

2 – Worldwide animation news

2.1 – Dreaming of retirement

The core of European animation is public funding — but not every project is a cross-border co-production. Some are unassuming enough for one country to handle. Take Retirement Plan, a short from Ireland that has our attention lately.

It premiered last year in Galway, and it’s going to screen at SXSW this month. Its subject is a man named Ray, who fantasizes about the time he’ll have after he retires — the time to do everything he’s put off in his life. He’ll “read the 35 years of saved articles” on his laptop and write “a devastating yet optimistic piece of poetry.”

“I will get so good at meditation,” he says. “I will be so present. So aggressively present.”

Ray’s voice is that of Domhnall Gleeson, the Irish actor (you might know him from Star Wars or The Revenant). “It was a long shot but I thought our story — which is a mix of absurd and tragic — might appeal to him,” director John Kelly tells us. And it did.

Kelly came to this funny, poignant film through a personal experience. As he explains:

I had what you might term a panic attack on a short-haul flight. Not one of those messy panic attacks where people get angry with air stewards for not bringing over more tiny bottles of whiskey — this was a quiet, internal moment that probably no one noticed but me.

Long story short, I opened up my laptop to reply to some emails, and the 72,000 messages staring back at me from my inbox made me instantly aware of all the lists in my life. I was hit by the thought that — now I’m past 40 — I won’t have time for all the things I want to achieve in life.

Of course, rather than actually confront this bombshell, I decided to make a film about it.

Retirement Plan is structured as a list, which Ray reads point by point. The items on it change to reflect his shifting mental state. It’s a “kind of stream-of-consciousness” approach, Kelly notes. Things come “in bursts when Ray is excited or frustrated” and slower “when he’s on shakier ground.”

The effect is smart and subtle. And it leads to absurdity, even a degree of sadness, as “a rift opens up between what Ray is describing in his narration and what we’re seeing on-screen.”

Screen Ireland and RTÉ, a public broadcaster, provided the money for Retirement Plan. “The entire process lasted around eight months from start to finish, with three months of this being animation,” Kelly notes. He praises the two animators, Marah Curran and Eamonn O’Neill, for their “beautifully restrained performances.”

The highlight of the whole thing, for Kelly, was the editing process. In his words:

… we had over 100 shots in seven minutes, so crafting the joins and the flow over the course of the film was incredibly enjoyable for a control freak like me. Editing is a very intimate activity and I often find myself getting lost in the details, before suddenly realizing it’s after midnight. My favorite part, though, is coming in the next day — watching back what you made can be like opening up presents on Christmas morning (although sometimes, like on Christmas, the presents can be disappointing, too).

Kelly’s film is finally traveling outside Ireland this year — SXSW is its international premiere. We’ll be rooting for it in the months ahead.

2.2 – Newsbits

We lost Fumi Kitahara (56), a major publicist in American animation.

The Iranian film In the Shadow of the Cypress took the prize for animated shorts at the Oscars. Very well deserved.

In France, Cartoon Movie happens in a few days. It’s been a hub of Europe’s animated co-productions since 1999. This year, following the success of Flow, Latvia has the spotlight there.

The VFX giant Technicolor, headquartered in France, is collapsing. This is costing animation jobs around the world. Cartoon Brew has the story.

On Animation closed in Canada. It’s another casualty, notes Cartoon Brew, of the loss of Quebec’s “generous tax credit system.”

American animator Ian Worthington (Worthikids) has a new short, Evil Wolves, out on YouTube. It’s very funny.

Also from America: Victoria Vincent (vewn) worked with Adult Swim on a film called Snooze Quest, available on YouTube. It’s dark and unhinged, and more evidence that Vincent is among the country’s most exciting animators. She told AWN how the piece came to be.

In China, a Nezha 2 animator spoke to the press about the hard-fought process behind the film. Work was “painful but joyful,” she said, with long nights and lots of overtime.

One more American story: the first episode of Common Side Effects is free on YouTube. As a reminder, many of the folks from Scavengers Reign are behind it.

Lastly, we wrote about Flow, Pixar and the evolution of CG cinematography.

Until next time!

Animated shorts made with the co-production system have won before — see Peter and the Wolf (2006). And one European feature, Aardman’s first Wallace & Gromit movie, has taken the Oscar as well, backed by American investments. But Flow is the first feature internal to Europe’s co-production ecosystem to win.

Details about Brunner come from AWN, Cineuropa, this interview and an official pamphlet for Kirikou and the Men and Women (note that the last is a download link).

See this archived interview with Brunner.

Another great article, thank you so much! I can't wait to see Flow when it hits theaters in Japan on March 14th:)

Man. First independent animated film to do so. That's awesome.