Welcome back to the Animation Obsessive newsletter! Glad you could make it. Here’s what we’re doing today:

One — a look at Hayao Miyazaki’s labor activism during the 1960s.

Two — animation news from around the world

Three — a trove of restored Czech cartoons.

Four — the last word.

If you’re new to our newsletter, signing up is quick and no-effort. Get our Sunday issues in your inbox for free, every week:

Now, let’s go!

1. Miyazaki and the Toei union

We’re currently at a breaking point. The union that represents film workers, IATSE, is in “do-or-die” negotiations with the film industry. Even as streaming services make billions, the people who create its hits face brutal work hours and pay. If the industry doesn’t comply, it’s looking at a strike.

This is a story that’s played out many times before. Back in the ‘60s, one of the workers on the front lines was Hayao Miyazaki.

Toei Doga, the main anime studio in Tokyo, had hired Miyazaki fresh out of college. He started as an in-betweener on Doggie March, a collaboration between Toei and Osamu Tezuka. Miyazaki was 22 years old, and miserable.

“I frankly didn’t enjoy my job at all,” Miyazaki later wrote. “I felt ill at ease every day — I couldn’t understand the works we were producing, or even the proposals we were working on.”1

But he would find a lifeline in an unexpected place — Toei’s labor union.

Toei had a history with its workers. When it had staffed up for its first feature, Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958), its new hires started out making between 5,000 and 5,500 yen per month. As one former Toei animator has noted, that’s under $500 today. They couldn’t even afford rent, and found themselves hustling part-time to survive.

Things quickly got worse, too. Toei began setting animators to work in what they called “killer weeks.” These were devastating periods of unpaid overtime. In his book Anime: A History, historian Jonathan Clements explains:

It was understood that married staff and female employees would be allowed to leave on the last train; single male employees worked through the nights [...] there was eventually a predictable price for such unremitting late nights, irregular diets of junk food and cramped, repetitive labour, which led to occasional but notable lapses of health among the staff.

This took the name “anime syndrome,” like when one director collapsed during the production of Journey to the West (1960). That film proved to be the last straw for Toei’s animators. They formed a union and began to demand better hours, better pay and “supper during overtime.” Another point of contention was the pay gap — Toei could cut pay in half by labeling someone a temp, per union organizer Makoto Nagasawa.

Negotiations broke down in the second part of ‘61. Strikes began that December, and Toei retaliated with a days-long lockout. In the end, though, Toei accepted most of the strikers’ demands.

By the time Miyazaki joined Toei, the union had already won important victories. The anime legend Rintaro had made 8,000 yen per month soon after the strike. But Miyazaki earned 18,000 yen monthly in his first quarter as a trainee — and it increased to 19,500 yen after that. He was able to manage his hours, too.

“My idea was to go home at five o’clock,” Miyazaki recalled. “I was convinced that staying on at work was no good for me as a person.”

Conditions weren’t perfect during Doggie March (its director was working 230 hours of overtime a month), but it was a start.

Before long, Miyazaki fell in with Toei’s union, which had become an important cultural force. The team had “started thinking about things” for the first time, Nagasawa said. Union members read books, studied, held discussions and distributed news. This changed Toei’s atmosphere for the better. At a union film screening, Miyazaki saw the Soviet cartoon The Snow Queen and decided to stay an animator.

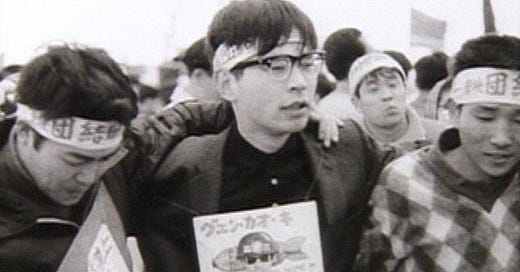

In 1964, Miyazaki became the union’s general secretary. While he’d been intrigued by Japan’s student protests in 1960, he hadn’t participated himself. This was new territory for him. “I was really at a loss then,” he said. “I had to take on responsibility. And I had to fight against the old guys who had interviewed me when I was a newly graduated greenhorn.”2

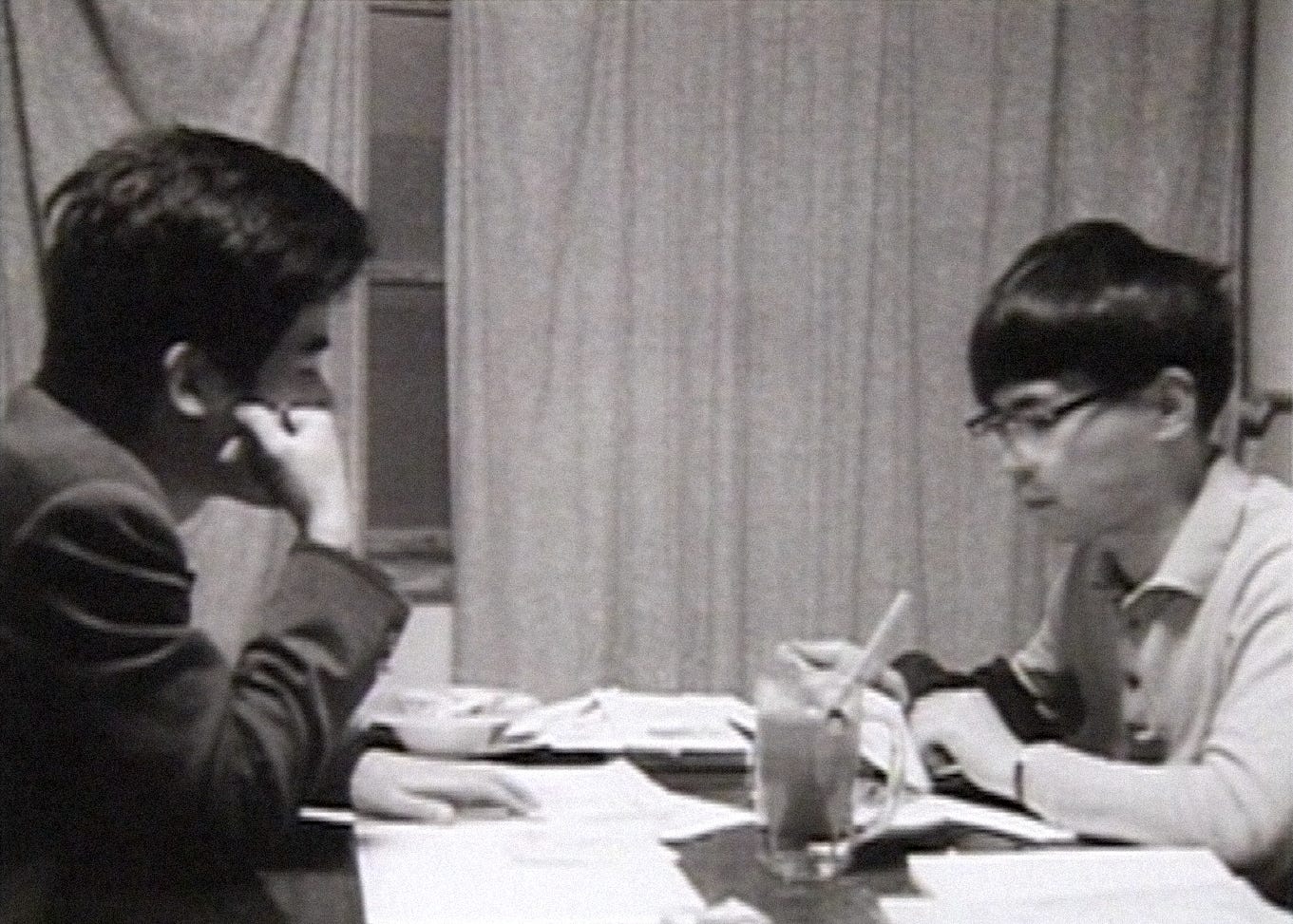

Still, he was making friends. One was Isao Takahata — vice president of the union during Miyazaki’s stint as general secretary.

Known as “Paku-san,” allegedly because of sounds he’d made while eating, Takahata was an imposing figure. He’d joined Toei in 1959, rising to the role of assistant director on The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963). Miyazaki described him as a “scary person” with plenty of enemies in management, but “very smart” and cool. Takahata remembered Miyazaki as “very young and naive.”3

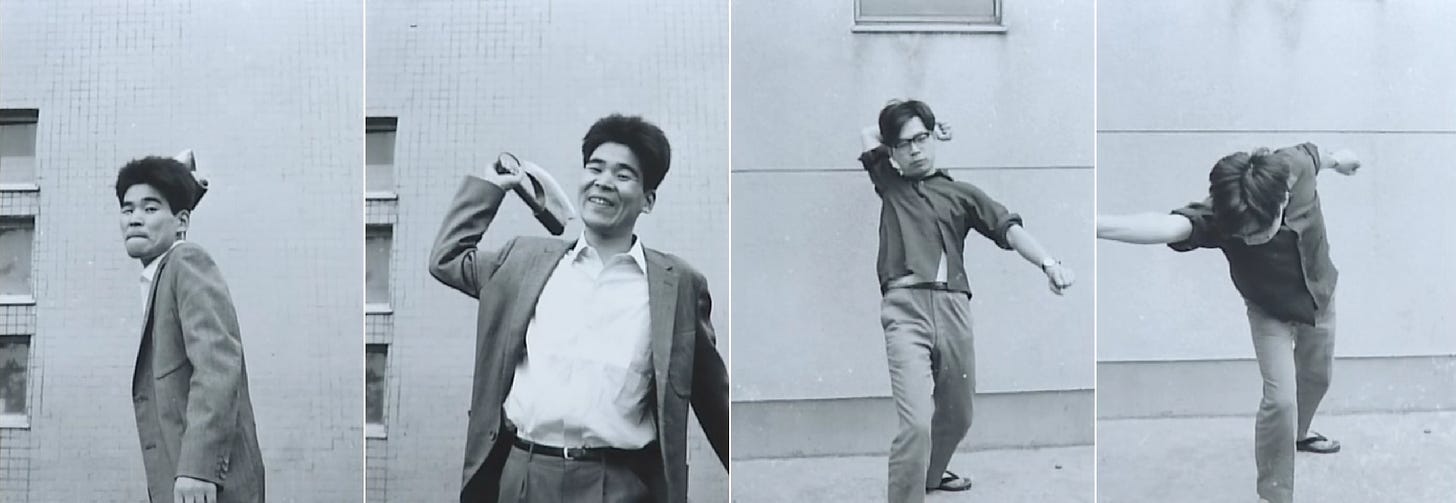

They liked each other. Often, they talked about movies and animation rather than union work. Animator Yasuo Ōtsuka, a friend of Takahata’s, was another member of their circle.

Their politics were far to the left. Miyazaki was a Marxist with an affinity for Maoist China. (While he later drifted away from Marx and Mao, he’s stayed strongly progressive.) Takahata, for his part, was a Marxist for life. During the Vietnam War, Miyazaki said that he and his friends were rooting for the Viet Cong.

All of this energy, from the union’s politics to its rich culture, was headed somewhere. Following another blow-up between Toei and the union, Takahata embarked in 1965 on his biggest project yet. It was Horus: Prince of the Sun — a landmark that essentially created the blueprint for all feature-length anime to come. Here’s how Miyazaki described the project:

Around that time we were badmouthing Toei Animation’s work for not being with it and silly and such. It was just when Sanpei Shirato’s Kamui-den [a manga series with leftist politics] was starting, and we were filled with an intense desire to create something new and different. The times really had an impact on us. The effect of the Vietnam War was really powerful.

Horus was enabled by the “solidarity among the main staff that had built up during their union activism,” per the book Starting Point 1979–1996. It trained Takahata, Miyazaki and many more in filmmaking. But it would also spend years in development hell, flop at the box office and win Takahata even more enemies. Its importance was only apparent with time.

In the end, Toei’s union gave birth to the future of anime. The influence of its aesthetic ideas is clear in Horus — but not just there. Miyazaki said of union activism, “[It] was a terrific training ground for me because I had to face my own weaknesses on a daily basis.” The art he encountered, the skills he learned and the friends he made in the union set the course for his entire career.

But the influence of Toei’s labor movement on the actual working conditions of the later industry is murkier.

In 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata quit Toei, leaving their union days behind. After founding Ghibli, Miyazaki remained an advocate for animators’ working conditions — but even his studio has been no stranger to crunch. It’s part of the industry. Today, the concept of a union for animators is basically foreign in Japan.

Even then, it’s worth remembering that better things are possible. IATSE’s recent moves should remind us that union power isn’t a thing of the past. If the will to organize is there, there’s hope.

Our feature story this week was made possible by our members. We’re investing more and more back into the newsletter, expanding our range with new (and sometimes rare) research material. You can help:

In exchange, you’ll get access to our exclusive bonus issues each Thursday. Our next one looks behind the scenes of Hayao Miyazaki’s beautiful music video On Your Mark. We hope you’ll consider joining us.

2. News around the world

Soyuzmultfilm’s revenue reaches 1 billion rubles

In Moscow, Soyuzmultfilm’s finances are on the upswing. It’s been a transformative few years — “30 million in losses in 2016 and a billion in revenue this year,” studio head Yuliana Slashcheva announced this week.

As she pointed out, there’s been a dramatic increase in production speed compared to the Soviet era. Soyuzmultfilm has three features and 16 series in the works simultaneously. “One episode of Prostokvashino, which consisted of seven minutes, could be done for 2–3 years,” Slashcheva said, “and today we are releasing two episodes of Prostokvashino a month.”

Its entire strategy focuses on children. There’s too little demand to invest in adult animation, Slashcheva argued. On that note, Soyuzmultfilm’s Loodleville was just revealed as one of five finalists at the important MIPJunior Project Pitch. Its children’s series Coolix, the first cartoon based on a Russian comic, started airing today.

Slashcheva’s speech underscores a big change at Soyuzmultfilm besides the one she intends. The studio is backing away from its artist-driven roots, and the freeform creativity of the past. Its shows are profitable, but they often look the same — so that they can be made quickly, cheaply and at volume. There are exceptions, and Loodleville does look nice, but Soyuzmultfilm feels a little less like Soyuzmultfilm every day.

Best of the rest

Pavao Štalter, the Croatian filmmaker behind Zagreb animation like The Masque of the Red Death, passed away on October 5. He was 92.

In South Africa, Triggerfish and the Cape Town International Festival are doing a lot for new animators — including workshops, free online courses, competitions and more.

Amid reports of a massive 70% loss at Europe’s box office last year, Spain is giving €10 million to film exhibitors and €15 million to film productions — including the animated projects Rock Bottom and Olivia y el terremoto invisible.

In this week’s weirdest story, a new Thai series “promotes morality” in honor of the scandal-plagued king of Thailand. It’s called The City of Forests, Many Lives.

In Japan, a book of storyboards from the first Lupin the Third series launches soon. It includes boards from the Takahata-Miyazaki-Ōtsuka episodes. Collectors shouldn’t miss Cartoon Saloon’s Irish Folklore Trilogy box set, either.

This week, the Festival of Animation Berlin gave its top prize to Vadim on a Walk from Russia. Conversations with a Whale was named the best German film. Both were Annecy highlights for us.

An Irish-British-French series called Goat Girl is coming to Cartoon Network.

The Japanese film Poupelle of Chimney Town is due in America. Legendary animator Atsuko Fukushima (Akira, Kiki’s Delivery Service) designed the cast.

The anime series Shikizakura, which premiered yesterday, was made entirely in Nagoya, Japan. Good news for the project to expand anime beyond Tokyo.

Lastly, there’s a trailer for William Joyce’s film Mr. Spam Gets a New Hat. “This film is my most autobiographical tragedies and all,” Joyce wrote on Twitter, “but with the whimsy spigot on high.”

3. Treasure trove — Czech cartoons

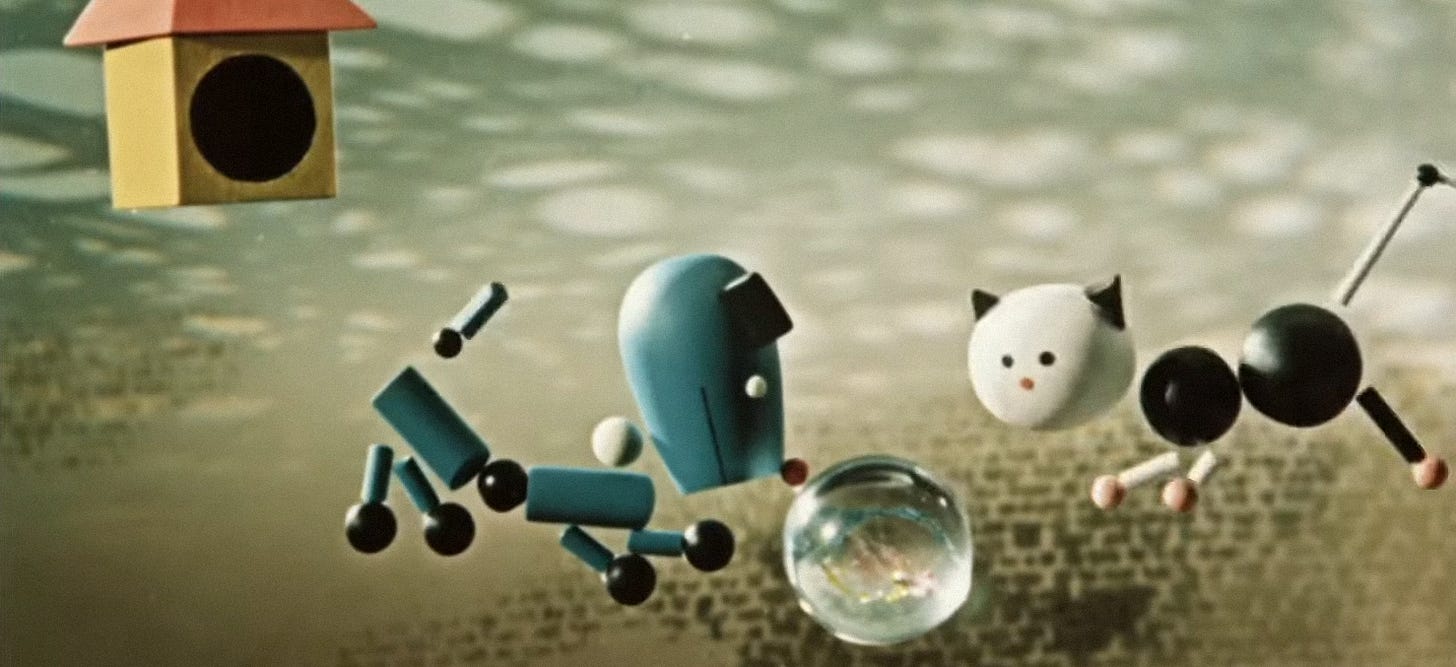

Czech cartoons have an amazing history — our bonus issue this week covered a chapter of it. But we didn’t have a chance to talk about the restored films that the Czech Film Archive uploaded to YouTube last year. They look great, and they offer a decent overview of classic Czech animation.

One of the collection’s high points is the work of Hermína Týrlová, the “mother of Czech animation.” She was a stop-motion master. See her early gem Revolution in Toyland (1947), where animated toys defeat a live-action Nazi. Or take The Marble (1963), a fable that blends creative, abstract design with snappy movement. The Blue Apron, a surrealist masterpiece from ‘65, isn’t one to miss, either.

One of the Czechs’ other titans of stop-motion, Břetislav Pojar, is present with work like 1959’s The Lion and the Song. This is a melancholy tale that’s different in both style and tone from the Týrlová films — an example of how huge the Czechs’ range was. Another example of that is the 2D comedy A Place in the Sun by František Vystrčil. It was an Oscar nominee back in 1961, and it’s still very fun.

All of the cartoons we’ve singled out are wordless, so there’s no language barrier. The Czech Film Archive’s full collection on YouTube packs many more films — some with dialogue, some without. We invite you to browse its whole playlist to see more.

4. Last word

And that’s all for this issue! Thanks for reading. We’ll be back with more next Sunday — and on Thursday, for members.

One last thing. This week, Substack added a new voice from the animation world. ND Stevenson (Nimona, She-Ra) has started a newsletter of autobio comics called I’m Fine I’m Fine Just Understand. Although it’s more about life than animation, we felt it was important to shout it out. Welcome!

On that note, we’d like to re-recommend The Line Between by Coleen Baik, a New York animator who likewise writes about life and art. Her newsletter has been a bright spot in our inbox for months. We’ve highlighted it before, but it remains consistently great. Don’t miss out.

Hope to see you again soon!

From the book Starting Point 1979–1996, which we use extensively as a source throughout the article.

From Turning Point 1997–2008, another frequent source.

From The Making of Only Yesterday.

Firstly, congratulations! Animation Obsessive is the best animation content I've ever found!

My name is Fábio, I'm brazilian, and I have an animation studio (molabe.tv). We are going to start a publication on the praxis of animation. I'm still putting together the first season of content, and I'd like to know if I can translate into Portuguese and publish the text ''Miyazaki and the Toei union''.

Thank you!

It's a beautiful overcast Monday morning here in New York City. I was still in bed, leisurely reading this issue with my coffee, marveling at how invariably history repeats itself, running through a myriad of emotions around the undervaluation of artists' work. It astounds me that labor which clearly takes not only an immense amount of time, orchestration, training, and love, work that is obviously valued by the public and consistently generates $$$, can be so decoupled from the hands that make. It makes me angry and I hope these talks result in a step forward. In 2021! I was going to say "unbelievable," but sadly I can't. Anyway I was wrapping up to write this comment when I saw the lovely shoutout—it made my day, early as it is. And it's nice to end on an up note. And as usual, learned a ton. Thank you.