Welcome! It’s a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and here’s what we’re doing:

1) On China’s legendary Duan Xiaoxuan (1934–).

2) Animation news from around the world.

A tidbit before we start — have you ever seen the animated titles for The Man with the Golden Arm? Saul Bass designed them in the mid-1950s and opened up a whole new approach to movie title sequences in the process.

With that, here we go!

1 – Filming ink

Animation from China doesn’t get the notice it deserves.

Big things are happening there. Just last year, Chang’an and Deep Sea brought world-level creativity to the screen — and a new look to blockbuster animation. But not enough people outside China got to learn about them, let alone watch them.

The same goes for many other recent projects, including the gory Dahufa (2017). Even when an animated movie from China does get a full release elsewhere, it may fly under the radar (see Have a Nice Day) or be sold as a mockbuster, localized without much respect for the work. It’s a bit like the early days of anime, when Nausicaä was obscure abroad and could morph into Warriors of the Wind.

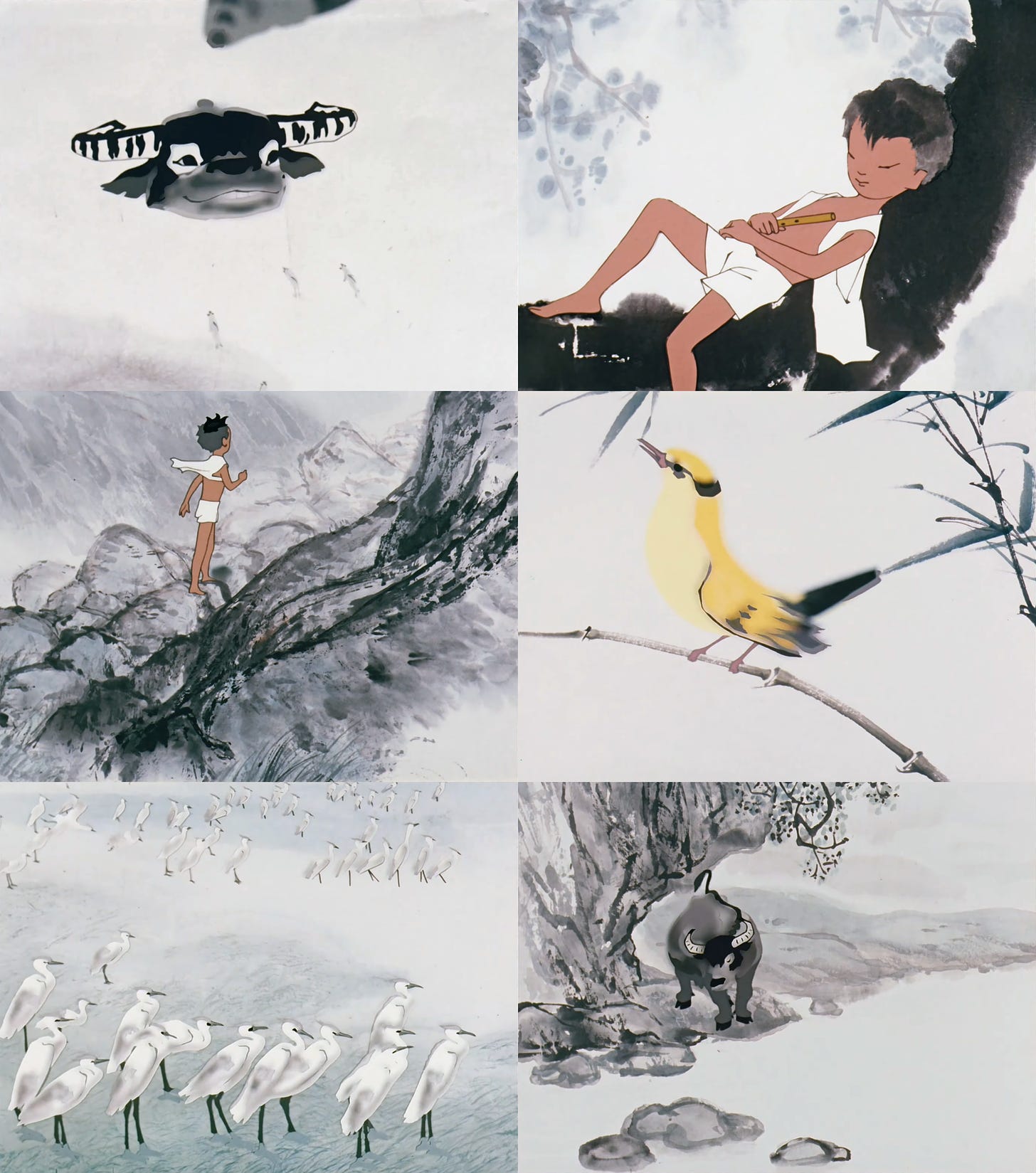

If today’s great films go under-seen, though, that’s doubly true for the Chinese animation of yesteryear. The ‘80s masterwork Feeling from Mountain and Water, an ink-wash painting in motion, is too little seen even inside China.

This is why the efforts of Fu Guangchao are so essential.

Fu is a young scholar in Beijing who’s spent more than 10 years documenting and sharing China’s animation history. Although his work hasn’t broken through abroad, he might just be the best animation researcher anywhere right now. His book We Animators (身为动画人, 2022), an oral history of Chinese animation, absolutely puts him in the running.1 We got a copy last month.

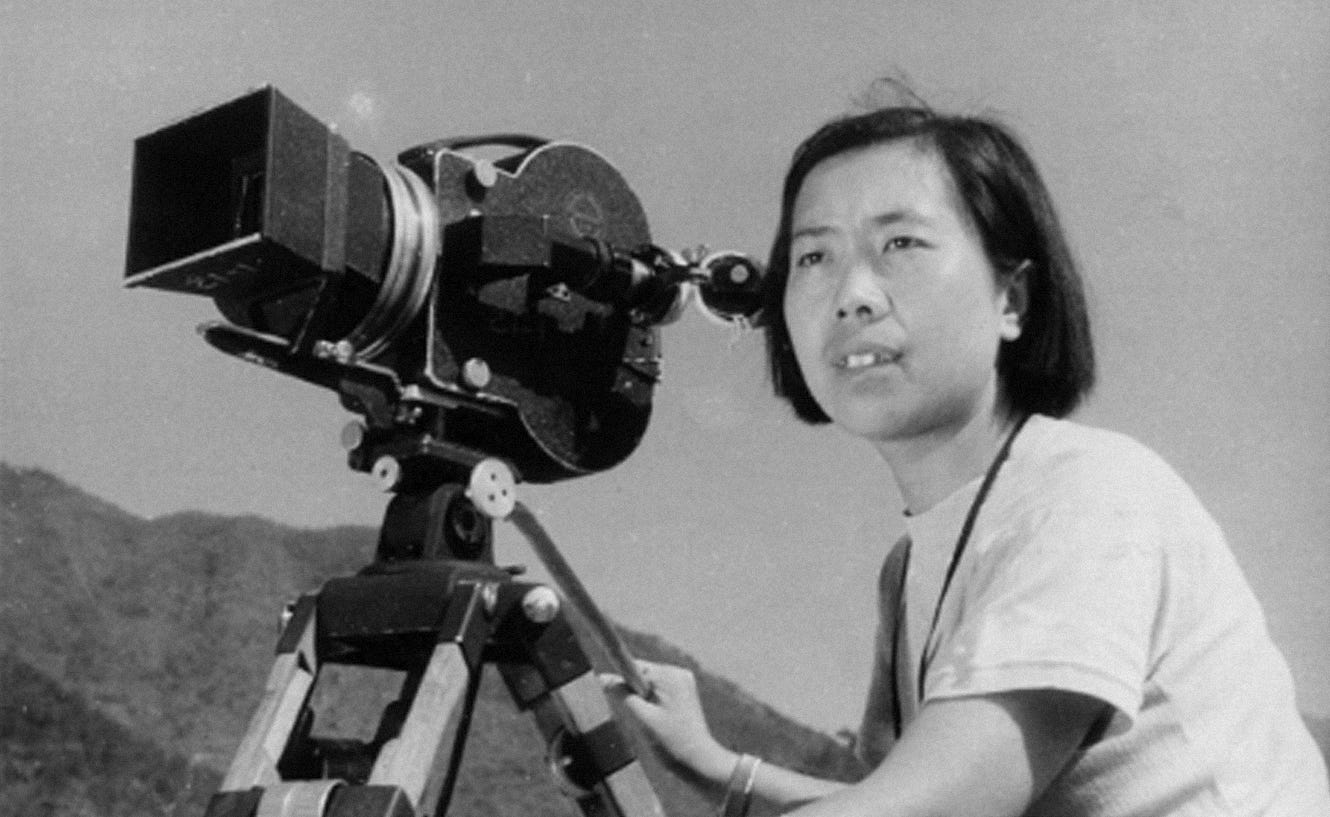

Fu and his colleagues have tracked down and interviewed many surviving veterans from Shanghai Animation Film Studio. Between the ‘50s and the ‘80s, it was the state-funded center of Chinese animation (it still exists today). We Animators’ first interview is with a Shanghai Animation legend who turned 90 this year: Duan Xiaoxuan.

Duan made her name as a camera operator — especially on ink-wash films like Feeling from Mountain and Water. In the days when all animation had to be shot on film, this job was critical. But it mattered even more in Duan’s case, because ink-wash animation, a style she helped to invent in the ‘50s and ‘60s, relied on photography.

Today, digital tools give any animator the chance to try an ink-wash style. But the distinctive look of Shanghai Animation’s original ink-wash films, starting with Little Tadpoles Looking for Mama (1960), is all analog. It was animated on transparent plastic cels, like a Disney film. How do you make that resemble an ink painting on paper?

It wasn’t easy. But Duan and her colleagues were used to adversity.

She’d started in animation as a teenager in the ‘40s — a decade of turmoil for China, with World War II at the start and the communist takeover at the end (Duan was a communist herself). Animation was barely possible at that time. Duan once said this about creating the early propaganda cartoon Capturing the Turtle in a Jar (1948):

For a start, we didn’t have any film of our own, so we had to ask the sound recording team. It wasn’t official, but we took whatever they had left over and put it in our cameras. Sometimes we’d get halfway through only to find out that the film had already been exposed. When that happened, we could only stay up all night shooting it all again. Later, we used up all our paper as well and had to go to the secondhand market in Harbin to buy more. We made the colors ourselves as well, by hand. Despite the tough conditions, we were all dedicated to the cause and nurtured an important habit: even under difficult conditions, we could finish a film. The foundations of our spirit of hard work, struggle and self-reliance come from this time.2

Years of training and growth followed. In We Animators, Duan tells of learning under Tadahito Mochinaga, the man later behind Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. She recalls studying cartoons from the USSR, including Little Gray Neck (1948), and working on Thank You, Kitty (1950) in a newly communist Shanghai. Things were so dangerous back then that studio members guarded the building with rifles.

Duan wore a lot of hats in those years — management, technical experiments, idea input. She became a camera operator later in the ‘50s. As she told Fu, it wasn’t the straightforward role that some imagine. Shooting animation meant solving problems and being creative.

For the first true film she shot, Little Carp Jumping Over the Dragon Gate (1958), she had to create underwater lens distortion. This required her to add textural effects to the glass that overlaid the cel, then film the result in specific ways to make the art ripple.

Shooting experiments were on Duan’s mind in general. During the mid-1950s, she saw a Soviet cartoon called A Naughty Kitten (1953), whose careful use of out-of-focus photography tricks gave its animal characters a furry look. She submitted a proposal to test this style — as a way to copy traditional ink-wash painting, which the Shanghai animators dreamed of doing but had never achieved.

A series of events played out from there. Duan didn’t invent ink-wash animation solo and never claimed to — Shanghai Animation was collaborative.

It’s wrong to over-credit even the directors with these films. The auteur style famous in Japan (Miyazaki, Takahata, Kon) wasn’t how China worked back then. When Duan later visited Japan in the ‘80s, there was surprise that a camera operator was contributing so much to the creative side, too.

In 1960, the Shanghai team got an official nudge to test ink-wash animation. A key person in these tests was Qian Jiajun, credited by many with the idea of constructing each shot out of layers and layers of cels, stacked to emulate the effect of ink variation.3 Duan worked with artist A Da on the early experiments. Animator Lu Jin and camera operator Wang Shirong were involved, too. It was a long list of names.

In fact, Duan once said that “the whole animation department … [and] the whole photography department” got involved in developing ink-wash animation. But her own role has been recognized as irreplaceable. “I am the only one to experience the whole process from beginning to end,” she’s explained.4

The most important tool in perfecting ink-wash animation, as it ultimately appeared in Little Tadpoles Looking for Mama and Feeling from Mountain and Water, was the camera. Duan and the team developed an ultra-complex system to do it.

Ink-wash painting has ink diffusion and subtle textures that cels, even layered cels, can’t reproduce. To get that softness and gradation, each shot was exposed multiple times at different levels of focus. It seems that some of the countless cel layers were photographed separately and only unified on film through multiple-exposure tricks.

Balancing the effect was a challenge. After all, this was pre-digital. Film had to be developed before anyone could see the results of even one test.

To this day, few people know exactly how Duan and the team did it. In the ‘60s, the government declared the process a secret and (as she told Fu) refused to let Shanghai Animation patent it. A public patent record was a risk because foreign animators could read it. In We Animators, Fu argues that it’s absurd to continue this secrecy today — the technology is outdated. But we’re still waiting.

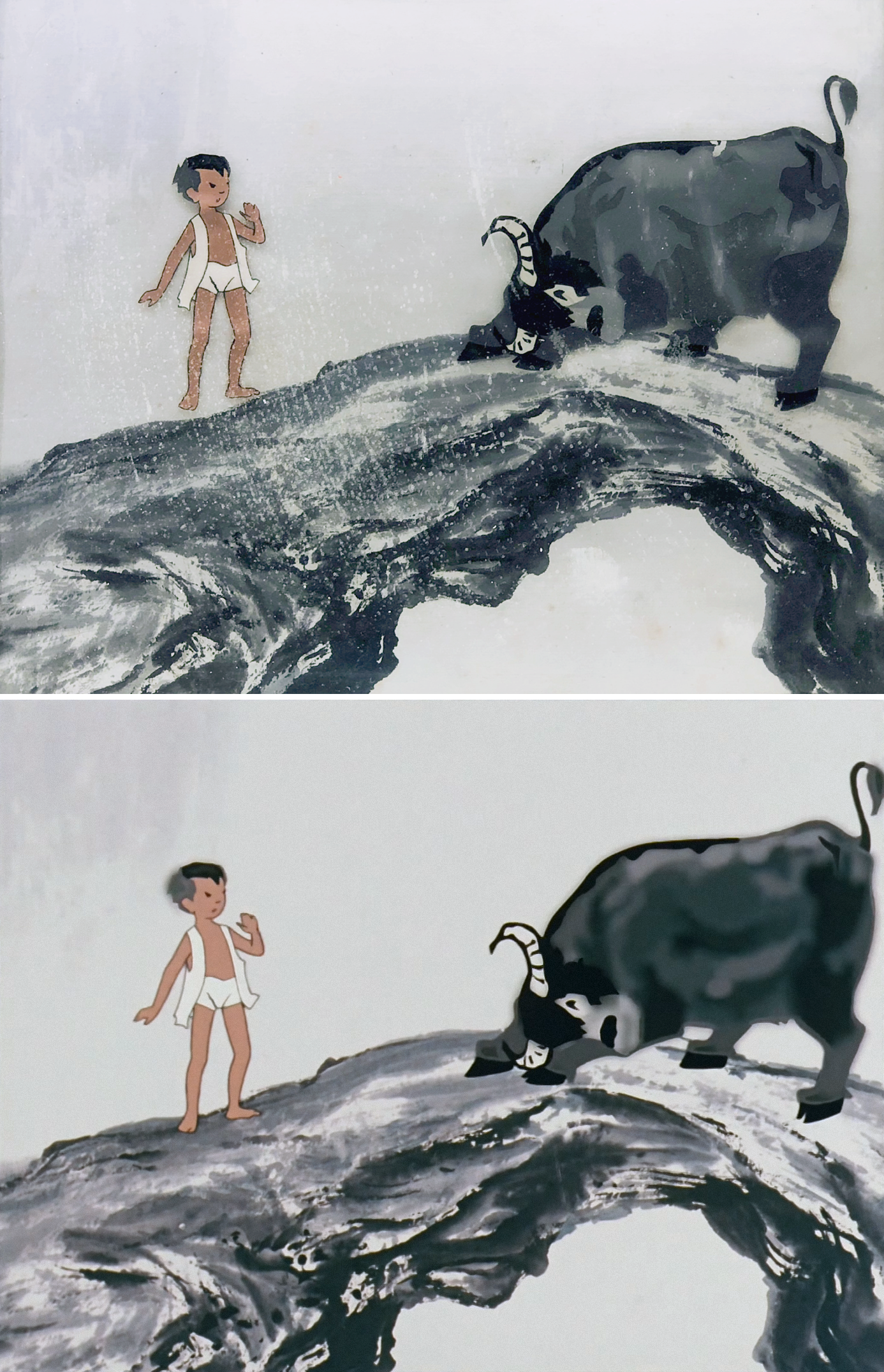

Alongside her (many) other projects at Shanghai Animation, Duan was behind the camera for the whole history of ink-wash films. The process was complicated enough that only four were made with the classic technique: Little Tadpoles, The Buffalo Boy and His Flute (1963), The Deer’s Bell (1982) and Feeling from Mountain and Water (1988).

That 19-year gap between the second and third ones came because of the Cultural Revolution. Under Mao, ink-wash animation was celebrated as a national treasure in the early 1960s, then denounced as a “poisonous weed” in the mid-1960s. Duan was condemned for her role in it, but others at the studio got more of the blame.

In the ‘80s, after the Cultural Revolution, Duan and the crew needed to rethink ink-wash animation. Little Tadpoles had been shot on Agfacolor Negative Film Type G 334 — made in Germany. By the time of The Deer’s Bell, Shanghai Animation had switched to Eastmancolor film stock from America. It required a new range of camera tricks.

All of this led up to Feeling from Mountain and Water. The innovations continued. Like Duan has said, some shots even involved “splashing the ink onto the absorbent mulberry paper, and shooting the effect of ink diffusion with a live-action camera.” She went on:

This film took a good deal of work and numerous experiments to finish. … [It] was a real artistic breakthrough, even more than usual. … When we finally took the film to the first Shanghai International Animation Film Festival, where it received a gold medal, the chairperson John Halas was so moved when he watched this film, he said, “It was like I discovered a new continent here in China.”

Toward the end of Duan’s section in We Animators, a little-known fact comes up. Shanghai Animation stopped making ink-wash animation with the old process after Mountain and Water — but, in the ‘90s, it started to develop digital tools that could recapture the look.

Duan stayed involved in these efforts for decades. They included commercials in the ‘90s and the ink-wash scenes in A Harmonious China, a propaganda film for Expo 2010. Her work has extended as far as Goral Flying, an ink-wash feature in the works at Shanghai Animation since 2014, on which Duan was a consultant. The trailer is a few years old now, but remarkable.

In animation, very, very few people have been as closely linked to the entire history of a technique as Duan is to ink-wash animation. She may not have invented it by herself, but it wouldn’t exist without her. She wasn’t a director or even an animator — but, at age 90, her legacy is secure.

2 – Newsbits

In China, The Boy and the Heron finally has a release date: April 3. You can see its Chinese poster via Catsuka. There’s hype behind this opening, and the film’s recent Oscar win seems like it’s propelling that hype further.

Meanwhile, Miyazaki’s film is coming back to American theaters on March 22, and its English dub (the GKIDS one) is screening in Japan from March 20.

Check out Snif & Snüf on YouTube. It’s a short by American animator Michael Ruocco that’s like a mix of Looney Tunes, Zagreb Film and a retro Disney cartoon.

In America, DreamWorks Animation seems to be coming undone.

There’s also serious trouble for animation in Argentina, where the right-wing government is defunding the arts. This hurts a venerable film festival and Ventana Sur — the film market Variety has called “the most important … in Latin America.”

In Japan, two lost episodes of Astro Boy have been found, restored and released.

Also in Japan, Ghibli Park is fully complete: its final area, the Valley of Witches, is now open. See photos via the film site Natalie.

In England, Aardman has new ads (here, here and here) out for the BBC. They’re done in the style of Creature Comforts — and the results are still warm, charming and funny, after all these years.

The Mechanical Monsters, the classic Fleischer Superman cartoon from America, has been restored for screenings at the Museum of Modern Art. Check out the before and after.

Another from Japan: the stop-motion samurai film Hidari just turned one year old. In celebration, there’s a new half-hour video that breaks down how it was made.

Lastly, we wrote about the mid-century boom of animated title sequences, from Around the World in 80 Days to Anatomy of a Murder and beyond.

See you again soon!

Fu has told us that the official English title of his book is We Animators: An Oral History Study of Animators in Shanghai Animation Film Studio – First Volume. It’s planned as part one of a series. He and his team have collected interviews and archival material for more than a decade (Duan’s interview was done in 2014 and 2020), so there’s much more still to release.

Fu’s project continues to draw attention in China — he’s recently been involved in a few TV broadcasts about Chinese animation history. With any luck, We Animators will one day not only get a sequel, but become available to readers internationally.

This quote comes from Duan’s essay in the book Chinese Animation and Socialism, the source for most of the direct quotes today. The bulk of the other information derives from We Animators, particularly her section.

As attested by Yan Shanchun and Wang Shirong in We Animators. Yan gave additional details in this roundtable interview. Duan has said that Qian Jiajun developed the cel layering technique for ink-wash animation, but didn’t invent it. With so many people involved, it’s hard to offer one final and absolute credit here.

The second quote in this paragraph comes from the book Comics Art in China.

Fascinating article - I remember referencing a film titled “Snipe, Clam, Grapple” for a commercial in the 80’s which was in an ink wash style but most likely cut-out and not straight ahead drawn animation.

The multi-exposure thing is interesting because it’s harder to do where you have a predominately white background in the final image, so perhaps they shot on negative film and used an optical printer to combine the various passes instead of in-camera..

Fantastic.