The Violent, Beautiful Animation You Probably Missed

What makes 'The Guardian' (Dahufa) so great.

In a paywalled article earlier this year, we wrote about the four words that everyone in Chinese animation knows: the rise of guoman. It’s a phrase that means something important in China.

No English word captures the full meaning of “guoman” — but it roughly translates as “domestic cartoons.”1 And, in China, the rise of domestic cartoons has been discussed and debated since at least the mid-2010s. Are they rising? Have they risen? Or is the rise still years away, as many in China argue?

When the animated feature Monkey King: Hero Is Back (2015) earned $153 million against a $16 million budget, something was clearly up. When Nezha (2019) made over $700 million in China, it proved Disney-sized success was possible. But many weren’t satisfied. As we wrote, the guoman conversation comes from the Chinese public’s:

… desire for an art form that competes toe-to-toe with the best of Pixar and Studio Ghibli, both in artistry and popularity. The rise of guoman is the rise of China’s answer to the top animation in the world, made with a Chinese spirit.

That’s a high bar. Even successes like Jiang Ziya (2020) can be criticized in China, and brutally. Reviews trash scripts and stories, and dismiss solid box-office performers as flops. When it comes to animation, China is its own biggest critic.

But some guoman projects do get mentioned in a positive light. Nezha, for one. For another, there’s a film that’s grown into a cult classic since its release in 2017. To its fans, it’s an example of what guoman should be. It’s called The Guardian (also known as Dahufa), and it’s never been widely released in English.

Our newsletter goes out on Thursdays and Sundays. It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — get them in your mailbox every week:

Let’s make one thing clear: The Guardian is violent. So violent that its appearance in Chinese theaters has been called “a miracle.” Somehow, it made it through censorship.

The Guardian is beautiful, too. It’s a well-shot and well-constructed action movie, with an expert grasp of film language — staging, pacing, blocking, editing, color design and more. The film arrived in China just two years after The Autobots (a Cars ripoff that’s infamous in the country) but it has more in common with Akira Kurosawa.

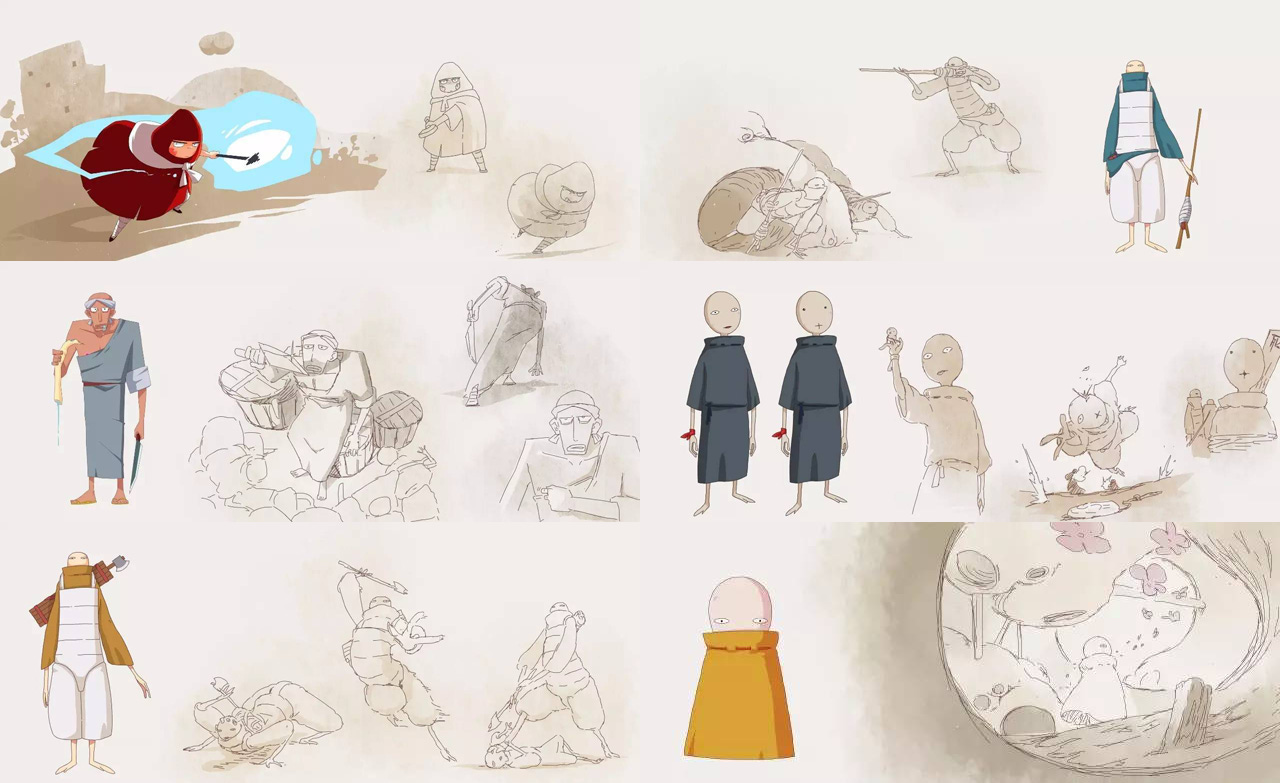

In The Guardian, our protagonist is Dahufa — the round, red protector of the Yiwei Kingdom. He’s searching for the runaway prince of his land, which leads him to an awful little place called Peanut Town. Here, Dahufa meets the oppressed Peanut People, who look vaguely human but aren’t. As China Film Insider explained:

They are taught to keep silent and to hate outsiders. All they do is keep themselves alive and worship their creator, the Immortal Ji’an, who rules the town with violence and lies. What Peanut residents don’t know is that they will be killed by Ji’an for the seeds in their heads as soon as they mature.

This is the setup to a thrilling, gory, sometimes funny, often strange film. Dahufa is an eccentric who spends much of the movie talking to himself and his pet bird. When he’s not talking, he’s in tightly choreographed gunfights with the government of Peanut Town, using magic to blast goons who have psychedelic green and purple blood.

It’s political commentary on China, too — even though The Guardian’s director, who goes by the pseudonym Busifan, often denies it in interviews.

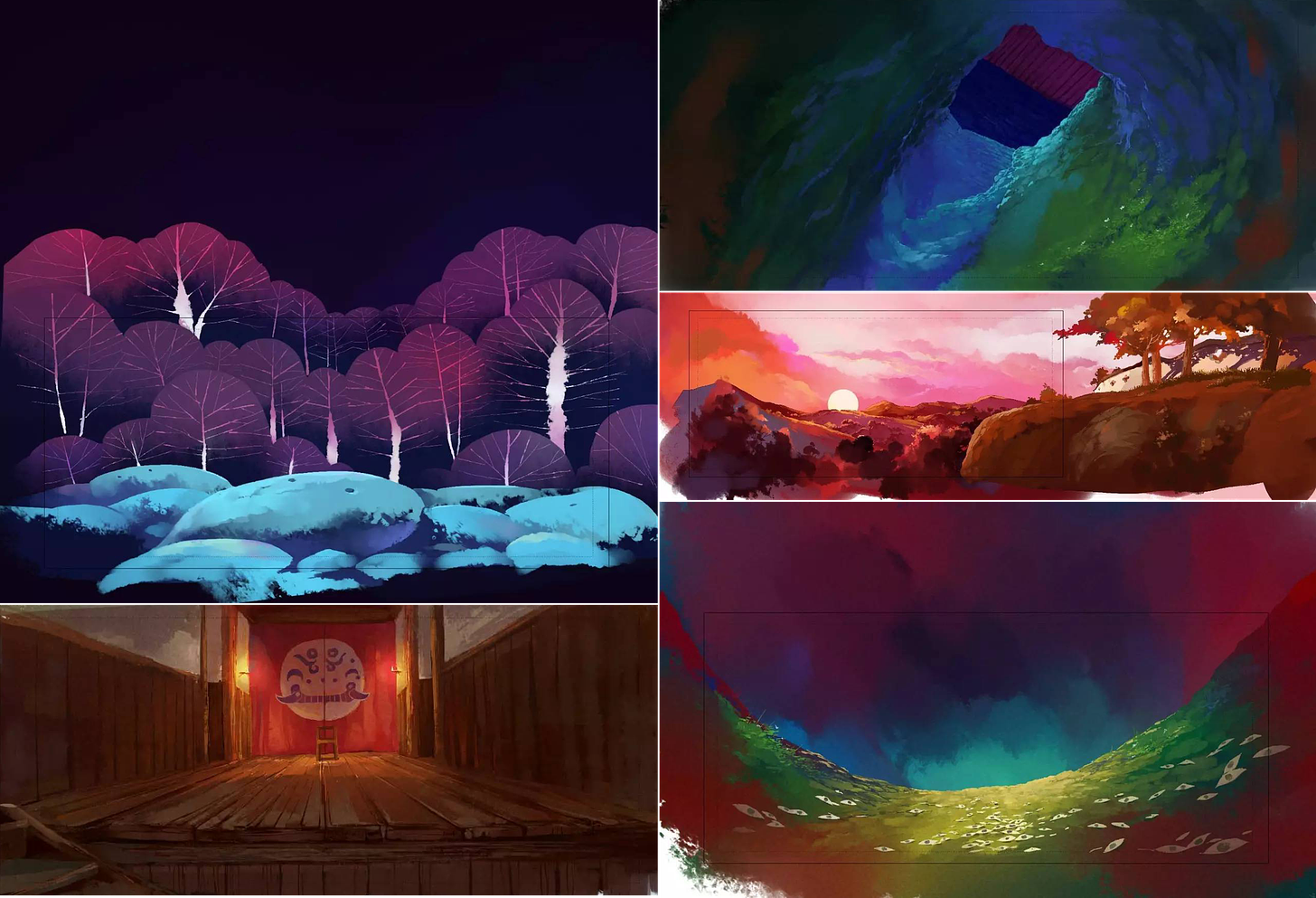

The Guardian came from a small team with a low budget — between $1.4 and $3 million. Busifan is a master of making it work. His filmmaking and storytelling carry, and his artists give us visuals full of character. There’s always a careful composition, a surprising angle, a sense of color that feels painterly. The animation is frequently good, but the film is viscerally engaging even when the motion is just okay.

This was Busifan’s first feature. That said, he already had a name among Chinese animators. He’s from the 2000s Flash scene, from the days when domestic cartoons were struggling. As we wrote in our profile on Cat, Flash provided the answer. Artists like Busifan cut a path that Chinese animation walks today.

Busifan came onto the Flash scene in 2004 with The Black Bird (now on YouTube in English). Already, you could see the seeds of The Guardian. Over seven episodes, he wove an unusual story about a lone warrior and his bird companion. The art is simple, but the filmmaking is much tighter and more consistent than it has any right to be. Chinese Flash often favored flash, but The Black Bird felt like it had substance.

“Some speculate from this that the author of The Black Bird is a professional who studied directing and screenwriting,” noted a writer in 2005.

Yet Busifan wasn’t a filmmaker. He wasn’t even an animator. In reality, he worked at a small-town telecommunications bureau.2 He’d grown up outside China’s major cities, living in rural areas and other out-of-the-way places.

“When I was a child, I lived in a very small village and town in the south of Jiangsu and Zhejiang,” Busifan recalled. Born in the mid-1970s, he spent his youth playing in the mountains and studying. He also read and reread The Adventures of Tintin and Kimba the White Lion, released in China as lianhuanhua picture books.

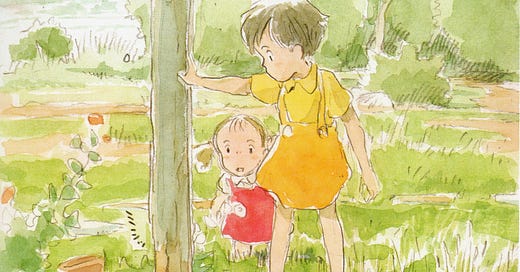

As Busifan grew up, foreign media started pouring into the country, and he learned that he’d been reading edited comics all along. He became deeply influenced by Japanese anime and manga (Vagabond, Miyazaki).3 When his attempts to publish his own comics failed, he decided to tell his stories in Flash — inspired by the American Flash series Ninjai: The Little Ninja. He taught himself the program.

With The Black Bird, Busifan crafted a key work of Chinese Flash. It lit up the imaginations of China’s indie animators, showing them that they could make actual movies. And it proved that Busifan had an innate sense of filmmaking and storytelling. He just needed to channel it.

This was the hard part, and the reason it took so long for The Guardian to happen.

Notoriously, The Black Bird was left unfinished. Busifan started to overthink it, getting bogged down in perfectionism. He disappeared from the internet — some wondered if he was dead. A few years later, he came back to animation, quitting his telecom job in the late 2000s and working at a few small studios in Hangzhou.

If guoman hasn’t risen now, though, it definitely hadn’t then. As Busifan learned the rules and regulations of the industry, he felt his raw creative spark fading. He felt stuck. Some of his fans could tell.

One of them was Shang You, a producer at the local studio Nice Boat Animation. He’d been a fan since The Black Bird, but saw something missing from Busifan’s ambitious short Miao Xiansheng: Yan Luo Dadao (2014). “I thought its image might not necessarily look exquisite, but its content [would] be highly expressive,” Shang said. “However, it turned out to be a work with fantastic images and [a] plain story.”

In early 2014, Shang met Busifan for the first time, finding him close to broken. They talked about a collaboration. Nice Boat Animation would put the money up — Busifan could do whatever he wanted, with no rules. The director replied that he wanted to do something violent. He needed to vent. Shang encouraged him to push the envelope.

“After hours and hours of conversation, he brought back my passion for animation and said he would support us to realize our dream,” Busifan wrote.

The Guardian was that dream.

Busifan’s desire to break free had grown intense, thanks especially to two main sources. One was Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained — which had an uninhibited quality that Busifan felt was missing from his own work. The other was The Black Bird.

“I went to look at The Black Bird [again], and I suddenly realized that behind those very rough visuals was a very, very pure creative state,” Busifan recalled. He was overcome. The spark he’d lost by conforming himself to the industry was right there, in 2004.

With The Guardian, Busifan wanted to go back.

A host of reference points went into this project. Westerns were a big one. Not just Django Unchained (the namesake of Xiao Jiang, the Peanut Person who’s arguably the heart of The Guardian), but also retro Clint Eastwood films. The Guardian is filled with borrowings from Hayao Miyazaki, too — especially the violent and strange imagery in Miyazaki’s darkest work, like the Nausicaä manga.

Then there were the martial arts novels of Gu Long. As Busifan said:

Gu Long gives me a feeling that’s more casual, very sharp, also more modern. When doing animation, I favor the style of Gu Long because there’s no need to move too much — you just start a motion and immediately get the end result; a character dies, and it will feel cool.

The Guardian doesn’t center on flashy, drawn-out battles. Every action scene is clipped and just-so — boom, boom, boom. That worked here because, as Busifan noted, it feels powerful despite requiring less animation. He tailored the project to its means, from its reliance on dialogue to its (at times) unsubtle use of tweening. Its style is a product of “poverty,” Busifan said.

That was like The Black Bird — and so was Busifan’s renewed spontaneity. The Peanut People’s design, for example, came when he saw a clay doll on a co-worker’s desk. It made him uncomfortable, and fascinated him. He wanted to use it in animation. When he started to overthink the idea, self-censoring, he resisted.

“I feel that if I feel it,” he decided, “others will feel it too.”

In the first year or more, there were four people on The Guardian’s team, Busifan included. Shang You watched over the project from Nice Boat. It wasn’t a feature yet — it was a series made for the internet. When Busifan took the project to Kickstarter in early 2015, he made it clear that it was a two-episode animation done in Flash. During his video pitch, the subtitles read:

I feel like the film reflects our team’s understanding of life, both happy and repressed emotions. Because of our (oppressed) living environment, we have a lot of stories we want to share with you guys. And animation is the best (safest) media we can find to illustrate what really is in our hearts.

They wanted to make something that could “speak to the anger and the frustration of the young generation,” Busifan wrote.

It was a bumpy road. Busifan’s venting went too far at first — he brutally killed off the entire cast in the initial version. Shang You recalled saying that “he’s in a mood, he needs to vent, it’s great to vent, but I can’t take it out and sell it.” So, Busifan dialed back, telling a better story in the process.

But selling The Guardian was still hard. Shang You took it everywhere. There was praise from video companies, and even a bit of funding, but no one wanted to distribute it. The project was too transgressive, too weird.

Shang’s breakthrough came around late 2015 and early 2016, when Coloroom Pictures took an interest in The Guardian. Coloroom is a kingmaker in modern Chinese animation — involved in Big Fish & Begonia, Nezha, Jiang Ziya and the Chinese localization of Your Name. Whatever “the rise of guoman” is, Coloroom is part of it.

The head of the company, Yi Qiao, saw one of Shang’s pitches. The Guardian was still a low-budget Flash series — even lower than the film we see today. But Yi was impressed. He asked, “[Do] you have the confidence to dare going to theaters?” Shang said that he did. That decision horrified Busifan.

On the big screen, Busifan felt, The Guardian would look “very simple and shabby.” It would embarrass him and the whole team, and maybe get laughed out of theaters. So, over the next year and a half, the team overhauled its project. The costs nearly bankrupted Nice Boat Animation.

Theater-grade voices and music were added. Visuals were touched up. (An outside company, The White Rabbit, added more depth by converting everything to stereoscopic 3D.) And the episodes were cut into a single narrative — first by Busifan and then by Angie Lam, a veteran editor renowned for her work with Stephen Chow.

Slowly, The Guardian took shape. Hype built. When the film released in July 2017, reviews were strong — and it did decently at the box office, with a take of $13.2 million. “It is a good enough result for us, as we didn’t promote the movie that much,” Shang said. It made a little money.

More importantly, The Guardian made a case for what modern Chinese animation could be — sophisticated, weird, artful and even a bit non-commercial. Out of the many good films in “the rise of guoman” era, it’s among the best. And, just like The Black Bird, it inspired other Chinese animators. It wasn’t a hit, but it mattered.

To date, The Guardian’s international distribution has been pretty limited. It’s played at festivals, and had a theatrical run in Japan — but it’s scarce in English. It deserves a bigger audience. This is one of the finest animated action films in years.

That’s a wrap for today! Hope you’ve enjoyed.

Right now, Busifan is making his second feature film — The Storm, due out this year. Since The Guardian, Busifan has gotten the violence out of his system. The Storm is instantly recognizable as his work just from the trailer, but it’s for families this time. Busifan is one of China’s most exciting directors, and we can’t wait to learn more about this project.

See you again soon!

“Guoman” is a contraction of guochan dongman. Dongman is another contraction — of the Chinese words donghua (animation) and manhua (comics). Both dongman and guoman can mean either comics or animation, or both. That said, it’s incredibly common for Chinese writers to call Chinese animation “guoman” without any qualifiers.

Note that guoman isn’t the only compound word used in Chinese discussions about animation. Another is the acronym ACG — animation, comics and games.

Busifan’s relationship to Miyazaki’s work is interesting. From the start, he’s borrowed endlessly from Miyazaki. Spirited Away is one of his guiding lights — and Miyazaki’s influence was a main reason Busifan joined the animation industry in the late 2000s. At the same time, he’s very uncomfortable when people compare his films to Miyazaki’s.

Just a quick (and very late) comment but I've been trying to find an export copy/DVD of this to watch/show students. Would anyone have any idea of how to get hold of one? It appears to be almost impossible to find!

Hello! Great article about a hidden gem. Love this newsletter, I always recommend to anybody in the industry ♡ I was wondering, is there any way to submit info for your world news section ( or any other section for that matter)? Thank you so much!