Happy Sunday! This is a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and here’s what we’re doing today:

1️⃣ How budgets empower and limit animation.

2️⃣ Animation newsbits from around the world.

For those just finding us — we do this twice a week. You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, directly in your email inbox:

Now, here we go!

1 – Taking risks

What does a great animated project really cost?

In 2023, major movies (see The Flash, or the new Indiana Jones) kept getting weak reviews and limited returns at the box office. Animation wasn’t spared — among others, Disney’s Wish scored low and its opening ticket sales “struggl[ed] to reach even the most conservative of expectations.” The film reportedly cost something like $200 million to make, before marketing. It was shut out of the Annies’ nominations.

What wasn’t shut out was The Amazing Digital Circus — an indie hit from YouTube that broke viewership records last year and had a bigger cultural impact than Disney’s latest. (The exact budget for it isn’t clear, but its Australian creator, Glitch Productions, put the per-episode cost of its previous series between $200,000 and $300,000.)1

Then you have fellow nominee Robot Dreams, which Guillermo del Toro has called “masterful.” While it’s not a blockbuster, it is one of the best-loved animated features of 2023. And its budget would’ve been a rounding error for Disney. As Cartoon Brew wrote in December:

Big US studios shuttered their 2D animation divisions under the false pretense that it was too expensive. Now their CG films cost more & require a larger labor force.

Meanwhile, one of the finest films of the year — Robot Dreams — is a 2D Spanish production that cost only $6M.

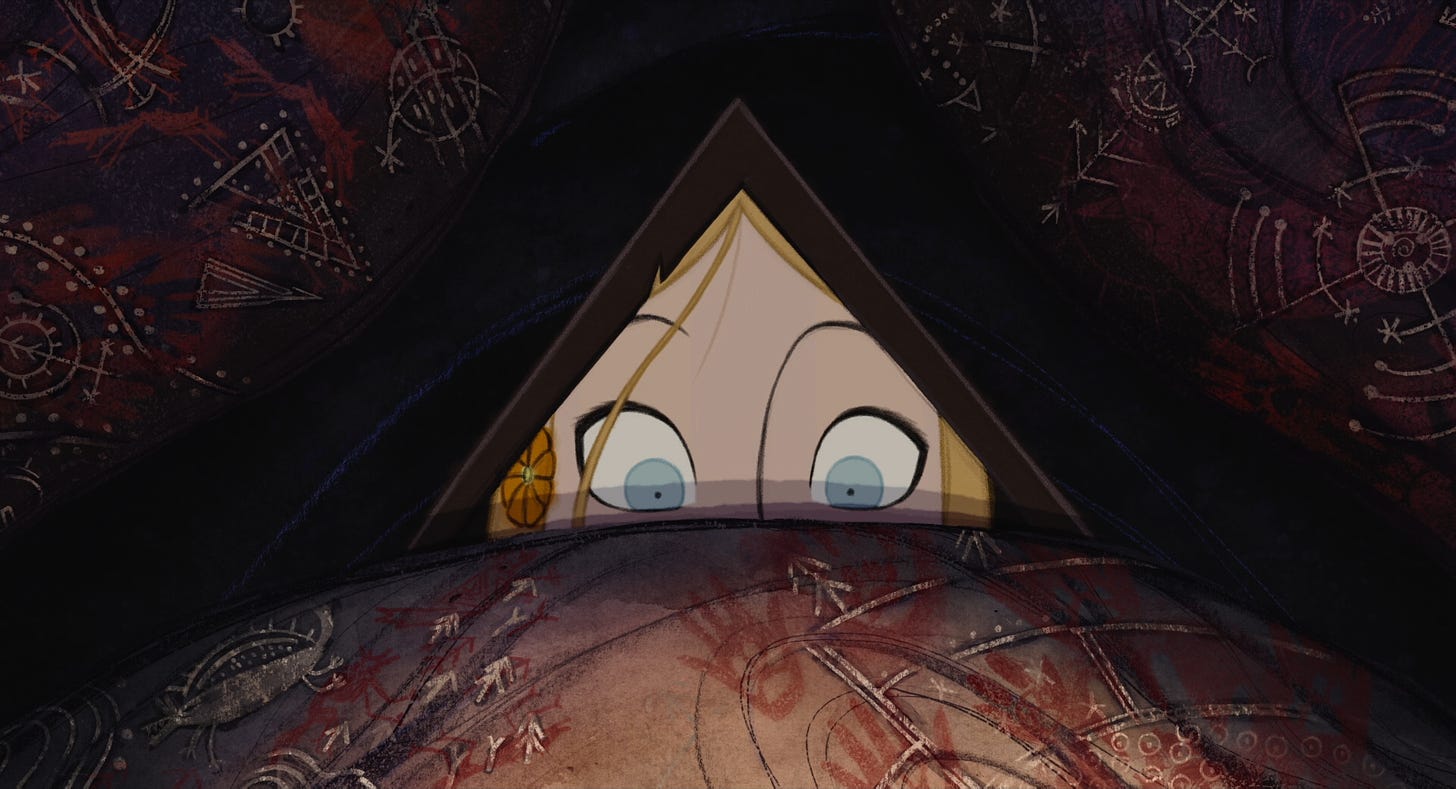

Robot Dreams isn’t alone. In Ireland, Cartoon Saloon made Wolfwalkers for €10 million a few years ago. That pattern repeats across Europe — The Swallows of Kabul (2019), an incredible feature, cost around €5.7 million.

With Kabul, directors Éléa Gobbé-Mévellec and Zabou Breitman told the kind of story that people say they want: mature, complex, original. And it has a beautiful watercolor look inspired by Ernest & Celestine. Despite the cost, you don’t feel anything missing. In fact, it’s a more complete and fully realized film than many with 40 times its budget.

It’s been clear for a long time, though, that money doesn’t guarantee a great animated movie.

Since the ‘80s and ‘90s, Hollywood has looked to anime for inspiration (we’ve covered this before). Yet Japanese animation rarely costs a lot. In general, the anime industry runs on shoestring budgets: investors gamble small amounts of money in the hope of winning huge returns. Artists have found ways to navigate that landscape.

Like Carl Gustav Horn wrote in a 2015 essay:

Although Japan has one of the biggest economies on Earth, its anime productions ... almost never receive the budgets needed to permit the smooth movement associated with Western animated films or TV shows. “Smoothness” is much too simplistic a measure by which to judge the animation that gets made in Japan, whose best artists have found ways to convey expressive movements with a stylized economy and individual artistic technique. Still, those same Japanese animators know only too well what they could achieve with more money, and even Hayao Miyazaki’s films, which generally had higher budgets than [Mamoru] Oshii’s or [Satoshi] Kon’s, were indie productions by the standards of Pixar, Disney or DreamWorks.2

That was especially true for Kon, who created masterpieces on the cheap.

Millennium Actress cost $1.2 million, while Tokyo Godfathers was $2.4 million and Paprika “about the same,” Kon said. His budgets were low even by anime standards. And not without reason: he had a habit of making commercial flops, and enemies.

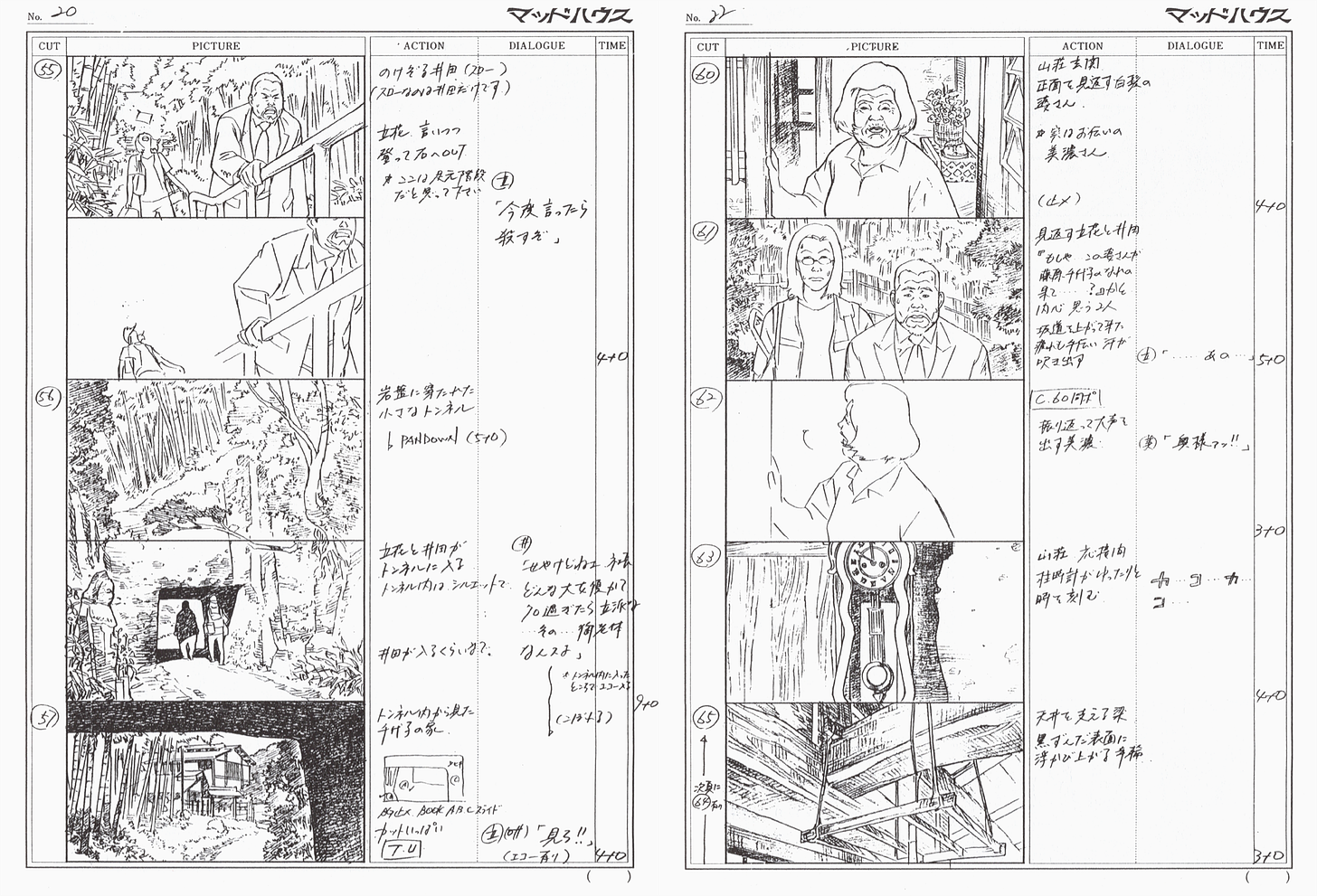

But the quality was there. He’d figured out how to do great movies with minimal backing — he’d designed his whole process around it. Those famous storyboards of his, as detailed as manga panels, weren’t just a flex. He used them to save time and bundle other steps (layout, location design) into his own drawings. Even the way he framed shots, he admitted, was tied to speeding up production and lowering costs.3

Kon resented his small budgets and complained bitterly about them. At the same time, he saved even harsher words for Hollywood’s excess.

In 2002, Kon got the chance to tour the California animation industry, visiting DreamWorks. He later talked about it in France. Again: Kon was good at making enemies, and he was known in the business for his acid tongue.4 But some of his comments are interesting to look back on. To quote a transcript by FilmDeCulte:

The imposing premises of DreamWorks, nicknamed “the campus,” amazed me. You could have grouped all the Japanese animation studios there (laughs). After this visit, I had the opportunity to speak in front of the studio staff. The single conference room was bigger than all of the production locations for Millennium Actress. But this vastness aroused neither envy nor admiration in me. The only thing I could be jealous of was the salaries (laughs). … To my eyes, the animated films produced by DreamWorks, whether Sinbad or Spirit, are of little interest. … What I find even more astonishing is to discover that someone like Jeffrey Katzenberg is in the credits. He left Disney to continue the same work at DreamWorks. The staff told me that the two studios were not alike. But I saw nothing but similarities. The United States has always praised personality. Their animated films embody the exact opposite: they are devoid of all identity. You never know who the director is …

For me, it’s not a question of judging which technique (2D or 3D) is better. Whatever the choice, what matters is talent. Not budget or manpower. … Why are these productions of so little interest? The reason is undoubtedly the inflation of credits and salaries. With so much money at stake, it is increasingly difficult to take risks and embark on innovative projects. We are thus witnessing a standardization of creation.5

Kon’s attack kept going. He argued that the 2002 American industry had “a kind of contempt for the child audience, which is seen as idiotic.” He felt that the films had too many storyboarders compared to Japan, robbing the end result of specificity. Pixar was the only studio he really praised.

A lot has changed since 2002, and Kon was an outsider back then. He didn’t watch everything America made or know how Hollywood operated from the inside — and he was mouthing off, as he often did. Although Kon took pride in his budgets here, he’d insulted and fired his producer on Tokyo Godfathers over investors’ hesitance to back another likely bomb.6

But a few points stand. Kon and his crew did ultimately make Tokyo Godfathers for $2.4 million on a short schedule. Meanwhile, a studio like Disney might’ve spent two to three times that amount to develop an intriguing project for years, only to scrap it on a whim.7 The excess was real, and bad decisions were made. By 2002, the notorious Foodfight! was already underway elsewhere in Hollywood, wasting tens of millions of dollars.

Risky animation did get through (see Lilo & Stitch), but plenty didn’t survive. The system was growing too inefficient and cautious. Even Disney’s method increasingly wasn’t working.

Which brings us back to the 2020s. Disney has been struggling again to connect to critics and fans with stuff like Strange World, a film that cost well over $100 million before marketing. Yet a director like Patrick Imbert can make The Summit of the Gods (2021), a genuine masterpiece, for €10 million.

“I’ve done animation for many years,” Imbert once told AWN, “and I know exactly what every single movement can cost. And I have to be frugal, but also reach the audience and immerse them in the story.” Imbert, a Satoshi Kon devotee, worked with a budget much larger than that of Tokyo Godfathers. But he was still in control of his project, and still taking risks.

Far more expensive movies pulled this off last year, too. The Boy and the Heron may be the biggest-budget Japanese film ever made — and it’s a dreamlike personal piece that feels totally non-commercial. It was a hit anyway. Sony took an unthinkable risk with Across the Spider-Verse and got another hit. Producer Phil Lord has posted that the team of 1,000 “made an avant-garde art film about an Afro-Latino kid and his family into a worldwide phenomenon.”

It goes back to what Kon said 20 years ago. These two films used their “budget and manpower,” but what defined them first was artistry, vision and sheer talent. The same was true of the best Disney films of the 2010s — like Zootopia. Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki has hailed that one as a “masterpiece,” but it wasn’t cheap to make.

Flexibility is a bigger risk at $150 million than at the ¥2.35 billion (over $16 million today) that Ghibli once spent to make Princess Mononoke. It’s still possible, though, and necessary. At least at Disney, that truth isn’t lost on the internal teams right now.

In a widely covered series of tweets last year, Wish animator Taylor Gessler Lanning wrote that she was “proud” of the film, but aware that “viewers demand more from this art form.” She continued:

It will take time. Disney was almost dead before Little Mermaid. We need new creative geniuses to take what people love about animation & make it fresh. How we will do that is unknown, but I feel confident we can make it happen if we keep pushing ourselves as artists and taking RISKS.

2 – Newsbits

Correction: Last Sunday in this section, we linked two mainstream news reports about a supposed artist on Studio Ghibli’s latest film. The story was subsequently debunked. We apologize for the error.

On that note, the Colombian branch of Women in Animation published an excellent list of real animation workers, ranging from veteran Cecilia Traslaviña (Silence Lives Within Your Window) to newer artists like Carla Melo (Sometimes Two Herons).

Possibly the best animation of the week is Wizard Beer by American animator Ian Worthington (Worthikids). Don’t miss his short behind-the-scenes video about it, either.

There’s a new, updated edition of the American art book Drawing for Nothing. It’s a free chronicle of unsung and unmade animation, now almost 500 pages long.

Per Catsuka, the Chinese film The Storm has an English trailer and will screen around the world, including in North America. Meanwhile, its director spoke to Anim-Babblers about the thinking behind the project.

The American outlet Animation Scoop spoke with Tal Kantor about Letter to a Pig, an Oscar nomination hopeful. It’s still free on YouTube for a limited time.

In Mexico, two educational programs are looking for applicants: the Jenkins-Del Toro Scholarship, and a course on “production and financing for independent animation” by Cinema Fantasma (Frankelda).

In Taiwan, director Vick Wang discussed his new feature Luda, which took him 10 years to make on a budget below TWD 60 million (around $1.91 million). He was searching for a “Taiwanese style” of animation. See a subtitled trailer here.

The American surf documentary Stoker Machine, a mix of live action and animation, is now online. It’s been winning at festivals for a while. Director Darieus Legg is a longtime reader of the newsletter and it’s awesome to see his film succeed.

One more from America: “fixer” Chuck Austen (She-Ra, Kipo) wrote in Animation Magazine about his “15 rules to keep your animated show from breaking.”

Lastly, we wrote about how Japan’s stop-motion legend Kihachiro Kawamoto went to communist Czechoslovakia in the ‘60s to learn his craft under Jiří Trnka, the great director of puppet animation.

See you again soon!

From Horn’s very good write-up at the back of Seraphim 266613336Wings (the Dark Horse edition).

We wrote about this in more detail in How Satoshi Kon Storyboarded Millennium Actress. Among other things, Kon framed the film to make it simpler to draw, keeping wide shots to a minimum. But he always tried to make his shortcuts purposeful:

… if the idea was simply to ease the burden of drawing, the work would become too impoverished. In addition to making the drawing easier, I needed to feel confident that it was effective for this work. Otherwise, I’d feel like I’m cheating. So, I had to come up with a reason, even if it gets called quibbling.

Hiroyuki Kitakubo, a friend and admirer of Kon’s, once wrote that the late director’s personal attacks on his colleagues “felt like a razor.”

Thanks to journalist Anton Guzman for introducing us to these remarks by Kon.

The producer in question was Taro Maki, who’d revived Kon’s career by supporting Millennium Actress after the failure of Perfect Blue. Maki recounted the situation with Godfathers in the documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist:

… for a director who still hadn’t had a hit at the box office, it was very difficult to finance the next film. For that reason, Kon told me I’d brought shame to the profession. In the middle of the project, I got booted off.

When Maki watched Godfathers after Kon’s death in 2010, he realized what an “intense experience” it truly was. “I had really underestimated its power when it came out. That was a shock to me,” he said. “It will be etched into my heart for all time.”

For more on a Disney project canceled after years of work and millions of dollars in development, keep an eye out for an upcoming issue currently in the works.

“Lilo and Stick” was, indeed, a masterpiece on the cheap. It was produced for a miniscule budget, at least miniscule for the Mouse House: $80 million. And according to the oral history at Vulture, was very much an artist-led picture, being produced at the Florida studio, an entire continent away from the big bosses in Burbank. If you loved the movie as I did, reading the article is a half hour well spent. https://www.vulture.com/2022/10/an-oral-history-of-lilo-and-stitch-a-hand-drawn-miracle.html

You'll commonly see people attribute cost to why big studios in the US don't make traditional animation anymore and it has always really annoyed me. US CG animated movie budgets ballooned to insane figures, and as you laid out here they are not all financial slam dunks. And of course, even if you doubled the budgets of the average Japanese/European budgets, they still don't even get close to what Disney/Dreamworks/etc. are putting up for these movies.

I'm just rambling but and I love a lot of CG movies, I just want to see some traditional features please!!!