Happy Sunday! Hope you’re doing well. We’re here with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter.

And this is a special one. Our lead story is a deep interview with the creators of The Glassworker (2024), a feature from Pakistan.1 Many haven’t had the chance to watch it yet — but it’s among the year’s best, most powerful films. An outside contributor, the scholar Claire Knight, goes behind its scenes today.

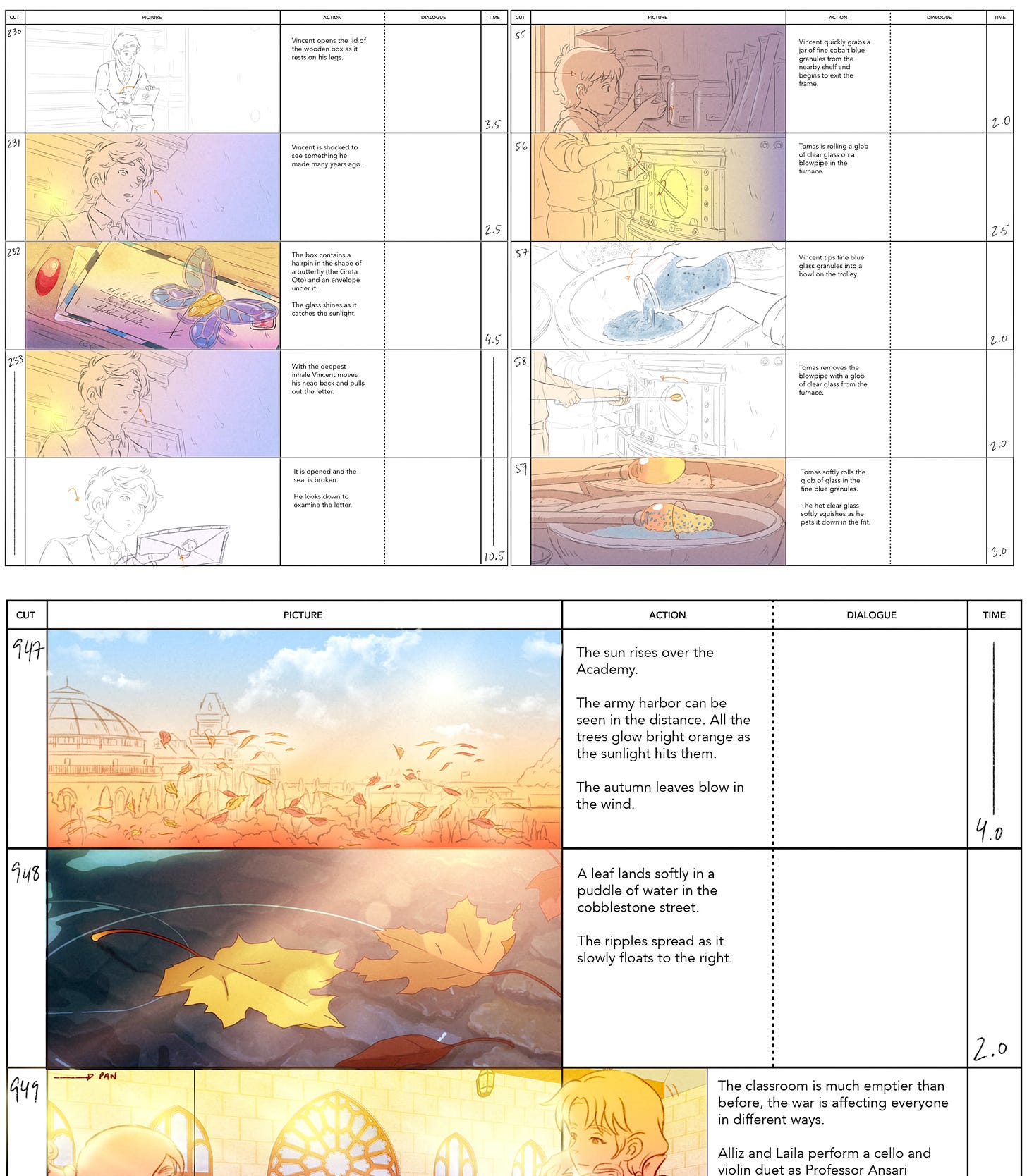

The Glassworker is a tale of war and art-making that, despite its fantasy setting, is really about our world. Heroes Vincent and Alliz are complex people from opposing backgrounds. Vincent’s father is a glassblower and a firm pacifist; Alliz’s is a military man in society’s upper echelon. Both shape their children as the struggle with a neighboring country wears away at their surroundings, their beliefs and everyone they know.

A question sits at the core of it all: what is art’s worth amid violence? The creators of this film have their own answer. “[W]ithout art and music,” a character says late in the story, “what do we have in this world full of conflict and war?”

And now, our slate:

1) Claire Knight goes inside The Glassworker.

2) Newsbits.

With that, here we go!

1 – Pakistan’s Oscar hopeful

Last May, while preparing for the mayhem of securing tickets to screenings at Annecy, I was intrigued by a certain Ghibli-esque visual for a film called The Glassworker. Was this a secret project from the famed studio or its stylistic acolyte, Studio Ponoc? To say I was surprised to see Pakistan named as its country of origin would be an understatement.

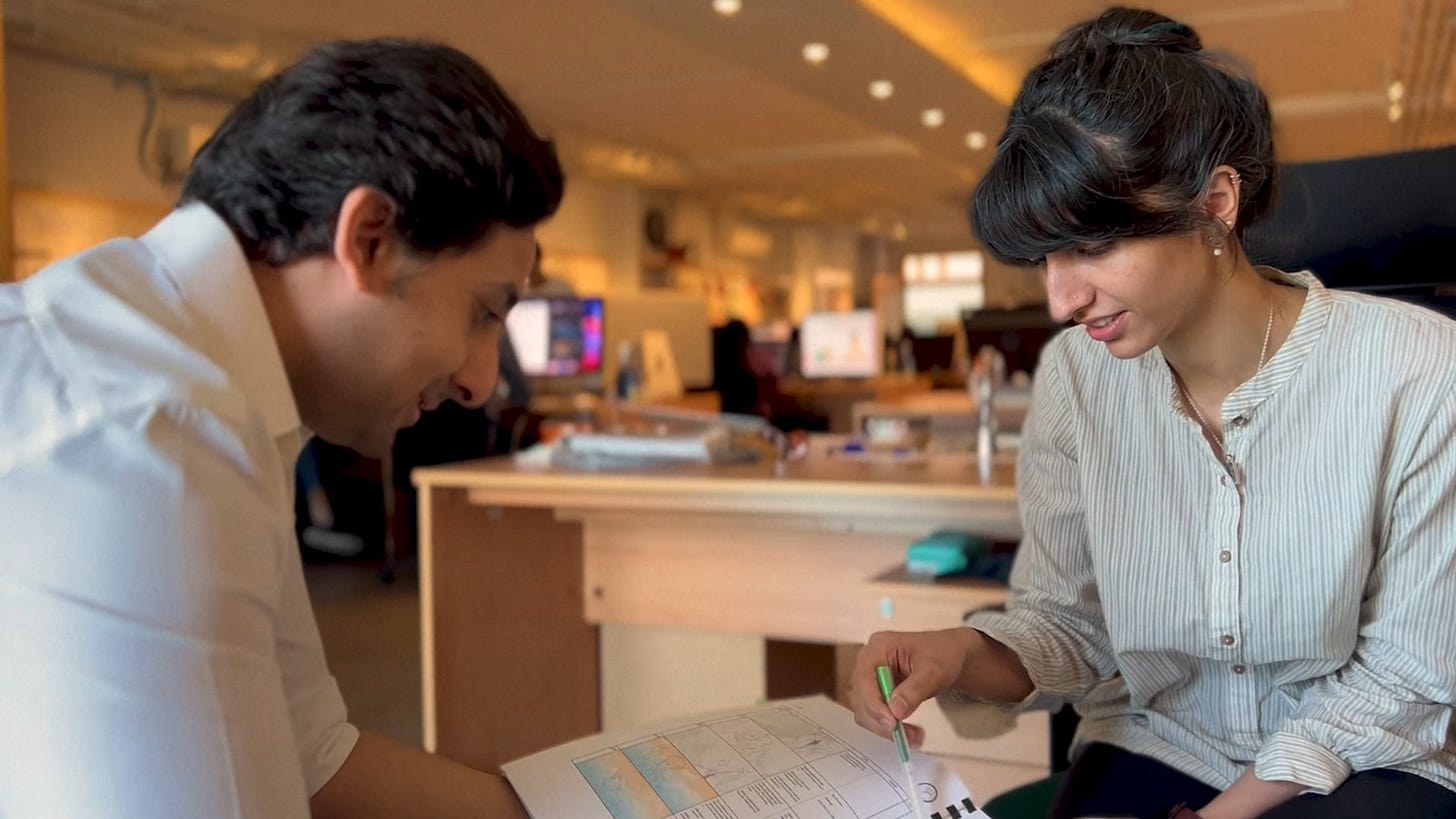

So, when the opportunity arose to interview the very young, very accomplished creative team behind this mystery film, I jumped at the chance. We spoke the day after its world premiere — about everything from recruiting dentists as animation workers to overcoming preconceptions about Pakistan. From the suitability of steampunk for a story set in Karachi, to the way that a random conversation with someone’s college buddy can make your dream possible.

Before we dive in, let me sketch out for you the commitment of this team, Usman Riaz and Mariam Riaz Paracha (husband and wife) and Khizer Riaz (cousin), as they sought to create Pakistan’s first feature-length hand-drawn film.

Usman, who trained at Berklee College of Music and has multiple TED talks to his name, was director, co-writer and co-composer, in addition to conceiving the film’s story. Mariam served as art director, second director, associate producer and background artist. Khizer helmed the production, line producing every aspect and helping to build the studio that the trio founded to make The Glassworker a reality.

Hopefully, the transcript below captures the dynamism and joy that they exuded as they shared their journey to create something out of nothing but their passion — and maybe a dash of that most valuable of ingredients, youthful naivety. Let’s go!

Why animation?

Claire: In the “making of” documentary, you say that the birth of The Glassworker as an animated film came in the moment when you were working out the story and realized that it couldn’t be done with live action; it needed to be animated. Was that when you first started considering animation and founding a studio in Pakistan, or had you been interested in the medium before?

Usman: I’ve been obsessed with animation since I was a child. I was [always] drawing and also studied the arts. But I never thought it was a possibility in Pakistan. And so I began pursuing my other passions. I pursued music: I’m a classically trained pianist and I write orchestral works.

But the turning point for me was when I went to TED. I spoke and performed there and I saw all of these amazing pioneers pursuing their passions and doing things like space archeology, which is Sarah Parcak, just sending out satellites and using thermal imaging to determine where archeological dig sites are. Now, seeing operations [carried out] at that scale, which she said nobody believed in, but [she] had a lot of passion for — hearing stories like that… I was like, if she can do this, maybe we can do animation in Pakistan.

But I never really thought about it further. Then when the idea for the film came and Mariam and I were talking, it clicked that, okay, we should be able to do this. I asked Khizer to join us on this journey and the three of us embarked on the animation adventure that took 10 years. I was 23 when we started; I’m 33 now.

Founding the studio in Karachi

Claire: In the era of outsourcing and remote work, what motivated your decision to found a physical studio in Karachi, a city without any kind of animation industry?

Usman: I think it was important to first just plant the flag down in Pakistan. [Showing] that we’re going to do this, we’re going to embark on this, and have faith that we’ll be able to pull it off. The foundation had to be strong. Everybody else [e.g. producer Manuel Cristóbal, screenwriter Moya O’Shea] came on board after we began, because when we started, nobody really thought it was possible in Pakistan. Every single studio or financier that we went to collectively said, “You’re crazy for doing something like this and it’s never going to work.”

So, first we had to prove to ourselves that it was possible and build our foundation. Then, when things started happening — we did a Kickstarter [and] raised $116,000 to make a pilot — and international talent started coming on board, that’s really when we knew, okay, we’re on to something and we can keep going.

Khizer: It’s also that, when you’re from a place, your infrastructure’s there, your network’s there, so there’s the ease of doing something at home. That was one thing. The other thing was the amount of money it would take to do it internationally versus doing it in Pakistan. We weren’t able to raise financing in one go. It was a drop, and another drop, and another. So the ability to spend that money efficiently [in Pakistan] just made the most sense, as we were able to stretch the amount we had.

It probably took longer, but I think that allowed the three of us and our team to be able to make cheaper mistakes.

Mariam: It was a passion project and we wanted to make sure that the pre-production and the production part was focused in Pakistan specifically. Obviously, we have a lot of international outsource partners and could not have done it without them. But the main story, the way it looks, the aesthetic — all of that was something that we wanted to be able to control.

Usman: At the end of the day, it was about maintaining control. And, also, I used to say this in my earlier TED talks: the idea of “bloom where you’re planted.” We had the opportunity to do it in Pakistan and we [felt we] should take advantage of the wonderful talent that is there in the country.

A most ambitious demo reel

Claire: Your inaugural work as a studio was a feature-length film. What was behind your decision to start with so ambitious — even impossible — a project?

Usman: I like to say that studios need a film to make. We had a film but we didn’t have a studio — we had to build a studio to make this movie.

So, while there were all of these nice, altruistic reasons to set up the studio — we want to inspire people, we want to show them it’s possible — ultimately the selfish reason and the truthful answer is, “I needed to make this film and we built a studio to make it.” And then everything else that happened around it was amazing.

So many people at the start would say to me, “Just make a short film! Why are you putting yourself through this?” And I just said, “No, a movie is powerful. A short film is beautiful; it’s amazing; it can help you in your career. But making a movie separates you from everybody else.” And it was tough convincing people to stay true to this course.

Khizer: Yesterday’s premiere [at Annecy in June 2024] proves that approach and makes it worth it. The impact that a feature-length film can have — that is what you only get in that premiere, when you saw the audience reaction. You don’t get that if you’re making ads, for example.

Usman: Which is another thing we were constantly told to do. “Make commercials.” Which is amazing and we do want to do it.

Mariam: We want to work on more projects on the side while also creating IP. That is something we definitely want to do, and we love that. But as our first project, we had a lot to say. And when you’re young and naive enough, you’re able to go on the journey. It was a good time to do it. Our film is in a way like the demo reel, our sizzle reel, for people to know that this is our aesthetic, this is what we’re good at.

Recruiting and training the team

Claire: At the premiere, you mentioned that the average age of the animators was 25, with 60% being women. How did you find and recruit them, building Mano Animation Studios from scratch?

Khizer: There was no infrastructure for animation [in Pakistan]. It’s not taught here. What we had to do was reverse-engineer everything. We had a wonderful team, a great animation director [Aamir Riffat] and character designer [Sofia Abdullah], and then the other leads that we started training. Everybody who worked on the film in Pakistan was an enthusiast and had a certain level of skill. So we put together a program to take people in and put them through a month-long [training course] with the fundamentals, and then they could start working on the film.

Usman: Because the team was so inexperienced, I drew an extremely detailed storyboard. I had to show exactly what the film would look like, what the composition of the shots would be, what would be happening in the backgrounds and even planning out the majority of the key frames for the movement of the characters. Just so that somebody who’s never animated before, but is a good illustrator, could come in and understand the theory a little bit. And then you can guide them and push them forward.

Khizer: In terms of finding the people who actually made up the team, we did everything. We went to every school and university, every arts college that exists, anybody who was a fan of the craft, because we didn’t really have much to show them. It was just an idea. [We were asking,] “Do you want to join us on this journey?” School tours, conferences, reaching out through social media and everything.

We were speaking with parents, trying to convince them [to let their son or daughter work with us]. One of them came and started asking us questions. “Okay, my daughter’s a dentist. Why are you convincing her to become an animator? Is there a future here? She has a career already.” So we had these long meetings where we were being interrogated about our dream, not just by ourselves or by people with money, but by the people we were hiring and their parents. It’s never come easy, which is great — that’s how it should be — but we became more grizzled in our vision.

And that dentist’s dad actually went home and said, “These guys are crazy enough that you can just join them. You’ll get it done.”

The company grew as we were doing this, so our first batch of artists were animators. When we realized that there were going to have to be different departments, we were able to siphon off some people who were struggling with the animation and keep them on in art direction, or in production, or in the legal department, or HR and finance.

Mariam: A lot of times, people would come in like, “I love anime,” or “I want to be an animator!” But when it came to actually doing it, a lot of them froze up or they left. And that comes, I think, from lack of exposure to how harsh it is.

Usman: Everyone loves watching animation. Making animation is a whole other story. That, we found out the hard way. But it’s good, like Mariam was saying, when they find out how hard it is, because then you find out who has the grit to actually see it through.

Animation is like glassblowing…

Claire: This focus on the arts really comes through in the film, but I have to ask, why glassblowing?

Usman: I went to Venice when I was 16 and I saw the Murano glassblowers. Ever since, I always wondered, “Why has nobody made a film on this?” Because the craft is so interesting. In 2006, a movie called Perfume came out. When I saw it, I was like, “So, they’ve done perfume. Why have they not done glassblowing?”

When the idea came to make our animated film, obviously there were a bunch of other concepts and themes we wanted, but I wanted it to be set around glassblowing. Just because the medium is so interesting and the process of creation is as interesting as the end result. Very much like traditional 2D animation, where I love the craft so much and all the technicalities, and the end result is obviously so beautiful as well.

I thought it would be an interesting mirror to our journey. “Glassworker” is a made-up word because the actual term is “glassblower,” but I just liked how that sounded. Glassblowing felt like the right medium to explore.

Mariam: We actually went to Peter Layton’s glass studio, which inspired us. We learned a lot from them; they really guided us. One of the glassblowers actually said that glass has a mind of its own. So you can plan as much as you want, but, in the end, you have to let it do its thing. I think we did face that [in making the film].

Blending localization with the global appeal of fantasy

Claire: Pakistan really shines in The Glassworker — with the vocals and the proper pronunciation, but also the sights and the sounds, and we can even imagine the tastes. But it’s also balanced with a steampunk aesthetic and has an almost universal fantasy feel to it. So how important was this balance between localization and globalization for you and for Pakistan’s first independent animated feature?

Mariam: The jinn is very much a piece of local lore that we’ve grown up hearing about. Our culture is very supernatural that way... I think that was an easy “in” — for us to believe in that mystical thing, which is why it was a very important element.

Usman: The jinn was like an unreliable narrator throughout the story. Is it Vincent’s friend? Is it not his friend? And I think ultimately, in the ending, we see its presence [can be read as] a positive or negative thing for Vincent.

But the localization and the globalization — to be very honest, for me, if the world is built solidly in your head, if you can see it and visualize it, and translate it, and explain your vision to the people who will be creating it, if you approach it with conviction, it’s going to work. That’s just my honest answer about it. I could see it working and was able to execute it and then draw it in the storyboards.

Also, Pakistan is very much like that. There’s a lot of technology being developed amidst extreme poverty, and that juxtaposition that you’re growing up around — you see it every day. Obviously, we didn’t show the negative side of that, but we showed the underdeveloped with the development in The Glassworker.

By making it fantastical technology, it’s an easier “in.” It would be very strange if we showed that world with cell phones, for example. But, if you see it in context with technology that is believable in that world, you buy it. With hand-drawn animation, the amazing thing is there’s no uncanny valley in terms of the visuals. Everything is drawn by hand; you’re not juxtaposing live action with CG sets. So it’s much easier to just understand and believe that this is the world and these are the rules of the world, and then you just start enjoying the story for what it is.

Khizer: There’s also the thematic element that made sense to put into the fantastical so that it’s subtler and more palatable for people. If you were to set it in the present day, there could be parallels that people might find off-putting or challenging to come to.

But there are also all the locations. People don’t realize that Pakistan was a colony of the British Empire, so there is a ton of colonial architecture, like the school that we showed, or the bridges. And there are a lot of idyllic pastoral settings in Pakistan: there are great beaches, huge mountains and mountain ranges.

David Freedman [who directed the English dub] said something really cool, that there is this mythical colonial vibe to the film, but there are also elements in the topography that are very much true to Pakistan. People don’t have that in their heads. They picture the hustling and bustling of markets, which is there. But that’s what they imagine — or a super barren land. When people sometimes assume that [The Glassworker] doesn’t seem like Pakistan, it’s also reminding them that there’s more to the country.

Mariam: Honestly, people who are Pakistani but have grown up abroad also face this. Like, “Whoa, where am I?” In Ms. Marvel, they depict that when she goes to Karachi. She’s like, “This is not what I was told.” They were probably told a version of [Pakistan] from their parents.

So, it is in its development stage, and a lot of great art is coming out of Pakistan. I think that’s helping people change their narrative. For example, Coke Studio is an amazing music platform based in Pakistan. And that’s being able to depict our culture in a way we want people to see it. I think that’s really important. Art is important for this, and especially putting it online and connecting with people.

A little help from international friends

Usman: We’ve had a lot of blessings while working on this project, but I think the biggest one is we’ve been able to work with a lot of established talent who just wanted to mentor us and help us because they wanted to.

People like Manuel Cristóbal, people like Geoffrey Wexler — who was the Chief of International at Studio Ponoc and Studio Ghibli’s English-language producer. People like Apoorva Bakshi, David Freedman, Moya O’Shea. But all of these people came on board because they were just excited about the level of passion that we had. And because something in their heart said, “I want to help these people accomplish their film and their vision.”

Those were amazing and we learned a lot from everybody, especially Manuel Cristóbal. And I have no idea how that happened.

Khizer: It’s a really funny story! Mariam was invited to the Women of the World Conference in Karachi. And one of the people that [Mariam and Usman] met there was this ad exec named Rushna. They were talking to her and said, “Yeah, we’re doing this animation thing.” And Rushna said, “Oh, by the way, I went to college with a person involved in animation. I’ll get you in touch with him.” That guy was Manuel.

Manuel is this animation veteran of so many years. He’s been to Annecy and won the Cristal here and won the Goya in Spain. So he came on board and said, “Yeah, let’s do this.”

Because we had been putting things out there about this film for so long, there was this sort of perception — I can say this now that the film is done — that people knew about the film but they didn’t know what would happen to it. Would it be made? It was just this thing that they’d heard about.

So, Manuel coming on board in early 2022 [brought] the cachet to the film that comes with his reputation. He applied for us to be in the Work-in-Progress [selection at Annecy that year]. Getting in was a huge deal. Not just from a personal perspective — it was like our coming out to the animation community, our being known and acknowledged and appreciated — but also [because it shifted] that perspective on the film, that it would be finished. That’s where Charades Films saw us and came on board.

On professionalism and overcoming preconceptions

Usman: I think it’s important to remember that it’s not just about the film and the vision. It’s about the machine that actually finishes that and then puts it out there. It’s important to take deadlines seriously and also to respect and adhere to the system, because that is how work gets made.

Anybody can take 25 years to make a movie and it could very well be amazing. The whole journey [for us] took 10 years, but we made this film in four-and-a-half years. Everything else — the Kickstarter, setting up the studio, training people — was a build-up to when we began production in 2019. We said, “We have to finish this on time and we have to do the best job that we can in this allotted time.” That is important.

Khizer: This is a line that we kept repeating. If you want to make an international-quality film, which was our aim, you need an international-quality work ethic, a professionalism. Now, the problem was that because we were going out to schools, for a lot of people who joined us, this was their first professional job ever. To create that sort of professionalism took a huge effort. But we signed a deal that said we would deliver the film August 31 and we delivered August 30. Charades said that it was the first time ever that they had a film delivered a day before the deadline. Most people ask for an extension.

But it was important for us to ensure that we delivered on time. There’s a perception problem that Pakistan faces, which is that if you work with them, you don’t really know what you’re getting into. That was something that we had to overcome. So it was extremely important to us to hit the deadline. Because anybody can make a film in 20 years.

Managing the circus: outsourcing and end results

Khizer: When we came [to Annecy] in 2022, a lot of the key framing was on track. But, in order for us to finish on time, once we signed that delivery agreement, there were 30–40 minutes that had to be outsourced for cleanup and the ink-and-paint stage.

I think we tested over 50 studios and a lot of them weren’t able to get the style. But we found two in the Philippines and one in Korea that were able to do it for the price level that we were able to afford and at the quality that we were going for.

All the pre-production happened in Karachi; 98 or 99% of the key animation and 70% of the background were done in Karachi. But, in order to finish on time, we had to spend a certain amount on outsourcing because that’s how films are made. People don’t know that — they think a studio does everything. Look at Ghibli’s credits or Ponoc’s credits. There are tens of studios that are credited.

It’s an entire circus that you’re trying to manage. So, it wasn’t easy. [Our team in] Pakistan had to ensure that things were ready so that we could start sending it out, send it to the editors, send it to the sound teams, send it to the voice direction teams, send it to the compositing — some compositing was done outside. All of these things had to be managed.

Usman: What I will just say is that I’m very happy with the visuals for the film. Because I wanted to make the best film I could in the circumstances that I had. And, in Pakistan, I don’t think we could have pushed it any more in terms of achieving those visuals. So I’m very, very pleased with that.

But none of that matters if the story is not impactful. So, I’m happy the story came through [at the Annecy premiere] as well and it moved people.

On taking the big swing and depicting childhood in war

Khizer: I mean, you took some big swings. There’s a tonal shift that happens towards the third act. There are also a lot of [changes in setting], which was a pain for Mariam to manage — the number of different eras and locations, and the back and forth that was happening from present day to the flashbacks. I think that the thing I’m happy about is, the audience got that [at the premiere]. I don’t think there was any confusion about what was happening. So I’m glad that we didn’t take the “safety first” approach for our first film. Take the swing.

Mariam: We do have to acknowledge that Vincent is a very lonely character and his father doesn’t make it easy on him. And, when you’re lonely, you’re kind of lost in your own head. The tonal shift happens really quickly. Watching it again, I was noticing things that I hadn’t before. I was seeing a person whose world is so small, and when your world is that small, you don’t think clearly.

Usman: What’s the Doors lyric? “People are strange—”

Mariam: “—when you’re a stranger.” I say that all the time. For sure.

Usman: And also just to mirror the harsh reality of war. War comes and everything is turned upside down. For Vincent, growing up with the conflict around him, with everything going on in his relationships, he snapped.

Khizer: It’s a mirror basically to what happened [for us]. The War on Terror happened in 2001, when we were 10 and 11, and that was overnight. Pakistan was in the midst of this war literally within a week of the Twin Towers. Suddenly our lives changed.

But, at the end of the day, no matter what context you’re growing up in, you still end up having a childhood. If you’re a child in that time, you still manage to have those childhood moments, even though the context may be supremely different to what most people are going through or what they imagine childhood to be like.

So, that’s what we had. There were checkpoints and curfews and two weeks off from school. And I remember just saying, “Oh, nice. Two weeks off.” And nobody was thinking, “Oh, my God, there’s a massive issue happening in the city.”

Usman: It’s only when you grow up and look back that you’re like, “That was a pretty strange experience.”

Mariam: It was just normal for us. I mean, now that I look back at it… You see Alliz is just happily running through barricades because it’s her reality. She’s grown up with it all around her because her father’s a colonel. But, with Vincent, he’s more protected in that sense.

Khizer: I like how people [in the film] get caught up with the [military] parade. People automatically assume this is a positive thing. Even though there could be connotations of danger coming their way, nobody’s thinking that when the parade’s happening.

Usman: Exactly. The colonel knows. He’s stoic and riding through the parade, but everyone else is just enjoying the moment.

A historic moment in British voice acting

Claire: The film premiered with its English-speaking cast, who are all British South Asian actors. Last year, the Royal Shakespeare Company put together an East Asian cast to do My Neighbor Totoro, and it was such a historic moment. And now your production is another historic moment for British Asian actors.

Mariam: It was really important for us. And because Pakistan was a part of India as well, we made sure [the actors could] be anyone from South Asia. For us that was important — to also understand the culture and to be able to pronounce the names properly that we had used. It was really lovely hearing their beautiful British accents, but they would pronounce the Urdu word perfectly.

Usman: The word “chai” randomly in the middle of it… Art Malik was absolutely phenomenal. He voiced Tomas Oliver, Vincent’s father. Yeah, Mariam is absolutely right.

Mariam: And it was amazing, honestly, working with David Freedman [on the dub]. He knew what he was doing. It was really fun, that whole process. Again, something new for us, doing it via Zoom. It was a very, very fun experience.

Claire: And you, Mariam and Usman, did all the scratch vocals yourselves, right?

Mariam: Yeah, that was honestly one of the funnest things. Just switching characters in the middle [of a scene].

Khizer: People legitimately thought, “Why didn’t you guys think the voice acting was done [after the scratch track was recorded]?” They did such a good job that it was considered already finished.

Mano’s nine lives

Claire: My last question is a little one: I noticed you have a cat in your logo. Is there a story behind that?

Usman: So, a lot of people assume when they hear “Mano Animation Studios” that it’s “hand” in Spanish. That is just an incredible coincidence. The Mano in the name came from my cat’s name growing up, so I thought it would be fun.

It’s also such a simple word, so I thought that the English-speaking world could pronounce it, and the Japanese would have a really easy time pronouncing it, so that was it. Manuel asked us, “You planned this, right? Hand Animation?” And we said, “Yes, yes, of course, of course!”

Claire: So, what should we watch out for from Mano Animation Studios? What’s next for you?

Khizer: Right when we finished production and post-production in September last year, we were able to get an outsourced service project. So we have the [Norwegian-Belgian production], Valemon: The Polar Bear King, that we’re working on as an outsource team. We’re doing 15 minutes of cleanup, in-between and ink-and-paint work. We do have another film that we’re in the concept and scriptwriting phase of, but we’ll announce that in a bit.

Great things lie ahead for this upstart studio! And, indeed, their journey has already inspired its own Studio Ponoc, in the form of LunaCanvas Studio in Karachi, founded this year by Mano alumni Aamir Riffat and Sofia Abdullah. Their impressive film may not be as long as Mano’s, but, together, these two teams are making a bold declaration to the world of animation: Pakistan is here to stay.

A huge thank you to Usman, Mariam and Khizer for their time, to The PR Factory for the opportunity, and to Jules and John and Animation Obsessive for the chance to share this inspiring story with a wider audience!

Claire Knight is a film historian by day and an animation enthusiast by night. She doesn’t really do social media, apart from Instagram — but that’s reserved for following cat videos, sakuga and Fortiche.

2 – Newsbits

Artist Cemal Erez of Turkey passed away this week, in his mid-70s. He was a painter and, working with his wife Meral, a central figure in Turkish animation. He spent his final years teaching at Istanbul’s Bahçeşehir University. Several of the couple’s films are available on YouTube.

Tod Polson, an American artist who worked on The Secret of Kells, spoke about his new film The 21, whose visuals draw from Coptic icons and those painted in modern Ukraine.

In Germany, Werner Herzog is developing his debut novel into an animated feature: The Twilight World. It adapts the true story of a Japanese soldier who “continued to fight a personal, fictitious war” after the end of the Pacific War.

In Croatia, still more restored cartoons are emerging from Zagreb Film. Check out A Modern Fable (1965) — a funny, creatively animated and vicious satire of the mistreatment of nature in the 20th century.

In America, director Dana Ledoux Miller went into Moana 2’s switch from a series to a film. She says that “Jared [Bush] and I started outlining it as a feature in September of last year” — but that Disney only made it official in January 2024.

Also in America, there’s serious pushback on the tentative deal between The Animation Guild and Hollywood, as industry figures like Michael Rianda, Matt Braly, Alex Hirsch and AP Davis speak out against its limited AI protections.

The sequel to Nezha, China’s biggest animated hit, is set to premiere next year in late January. Director Jiaozi is once again in charge.

Common Side Effects (from the co-creator of Scavengers Reign) is one of the most exciting American shows on the horizon. It has a new trailer and a February premiere date.

Catsuka reports on an upcoming book from Japan: Painting the Worlds of Studio Ghibli. It collects Ghibli background art — and, at nearly 570 pages, it’s a big one.

Lastly, we profiled four Christmas specials made and cherished in countries beyond America: Sweden, Finland, the USSR and Britain.

Until next time!

Claire’s conversation with the Glassworker creators has been edited for length, clarity and flow.

Thank you again for your wonderful articles. I am new to your postings and I was wondering if you list info about worthwhile film festivals? I just won the Experimental category from the Berlin Indie Film Festival. They sent me a very short email w congratulations but not much else. The other info is to come in a future email. Any insights you have on this Festival or any other would be appreciated. My animations pretty much fall into the Fine Art/experimental category. Thank you, Janet K.

Wow, such a beautiful article and the interview is shortened for clarity but still explains all the aspects of the making of the film. Also, loved the writing (.... or maybe it was Ghibli's acolyte) in this article and also how Clarie knew about LunaCanvas Studio (It's such an amazing thing that came out because of this film & their short film Luna does gives some Nausicaa vibes).