Happy Sunday! We’re here with another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our plan:

1) Alexander Petrov’s living paint.

2) Animation newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – A guide to Petrov

It’s a magic trick that never loses its mystery, even when you know how it works. The painted animation of Alexander Petrov, now 67 years old, still feels supernatural.

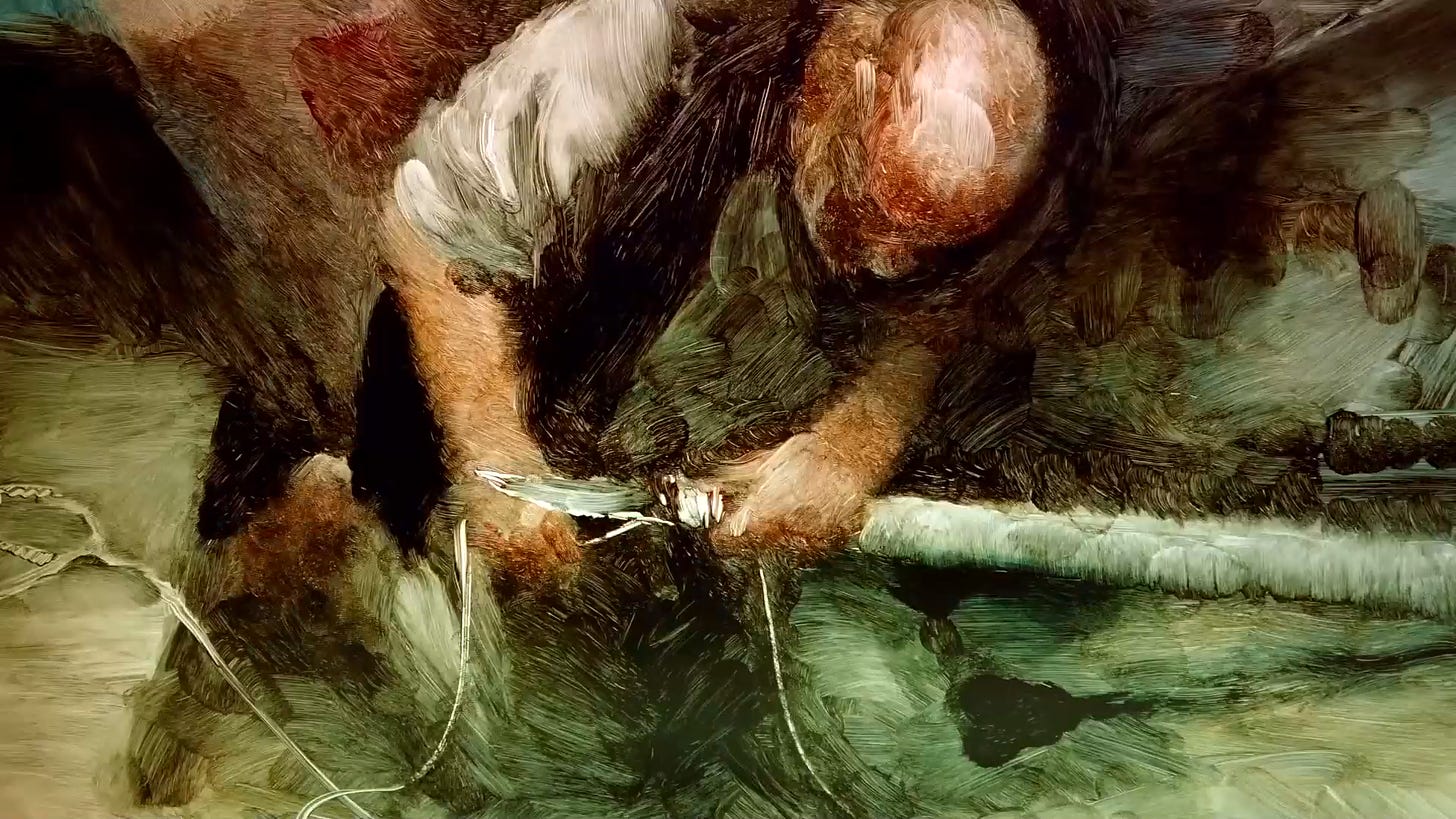

Petrov began to animate with paint on glass in the ‘80s, as an artist in the USSR. His method: create an image in oil paint, under the camera, and photograph it. He tweaks the painting, photographs it again — and so on. Bit by painstaking bit, he builds up an illusion of movement. His primary tools are his fingers.

He didn’t come up with the technique himself. Caroline Leaf made it famous with The Street (1976), a film known to animators in the USSR, and likely to Petrov. Its roots go back even further: some artists used paint on glass as early as the ‘20s.1

But, over the decades, Petrov has established himself as the virtuoso of this style. It’s brought him four Oscar nominations (including a win), plus countless admirers worldwide. He’s a master — one of the few to spend their career almost solely with paint-on-glass animation. It comes naturally to him. “It is the shortest and fastest link between my heart and the image I am creating,” he explained.2

Despite the acclaim, though, many people haven’t seen all of Petrov’s films — and most outside Russia are unfamiliar with the arc of his career. That leads us to our topic.

Today, we’ve put together an introduction to Petrov’s painted films that doubles as a viewing guide. You can click each title to watch on YouTube or Animatsiya (a site, run by a veteran translator, that legally overlays subtitles onto YouTube embeds of Soviet and post-Soviet animation). It’s an entry point into a serious body of work.

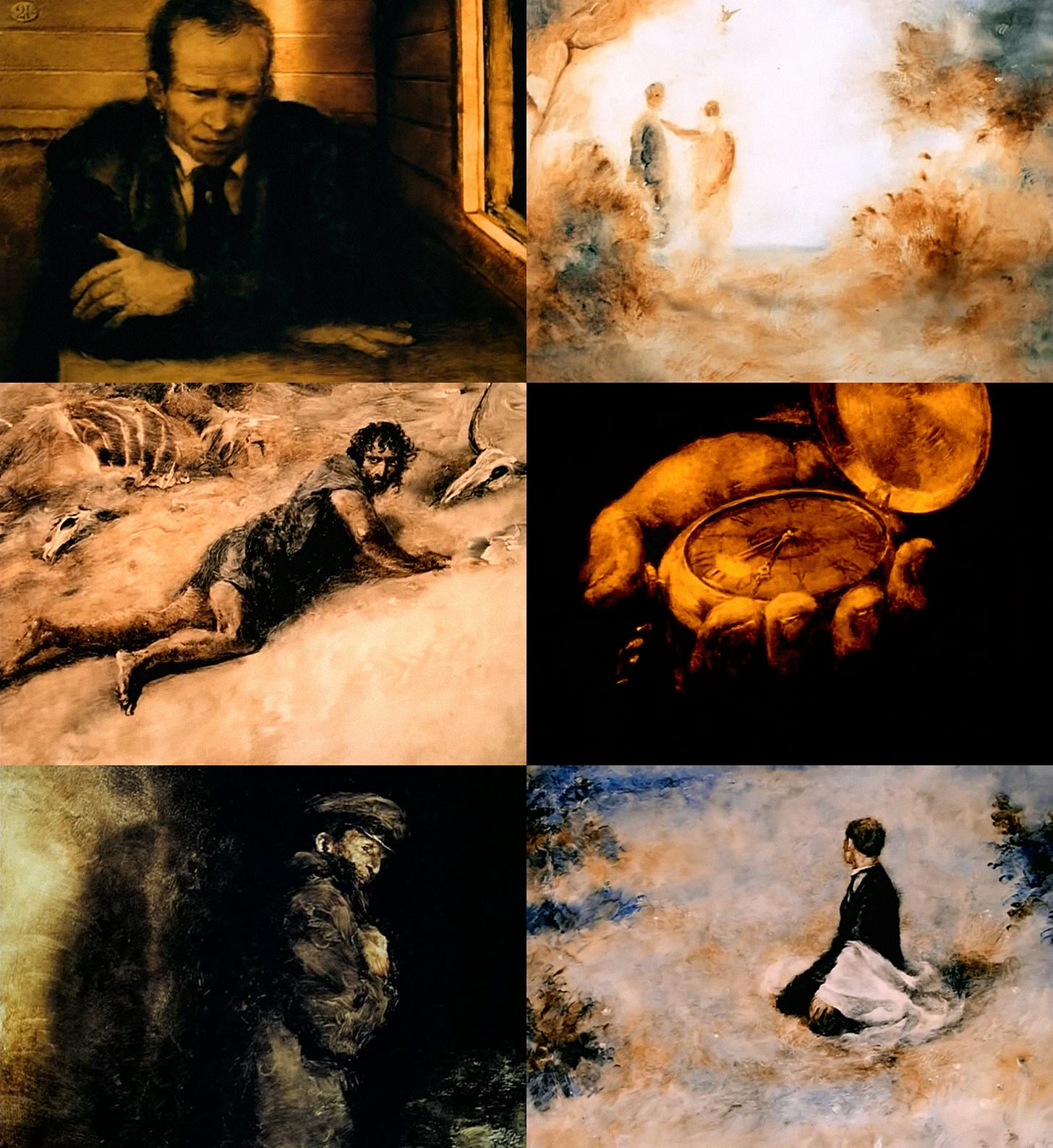

It doesn’t happen often, but some directors appear almost fully formed — already giants. Petrov was one. His first paint-on-glass film as a director, The Cow (1989), may be his masterpiece.

The film adapts a short story from the early Soviet Union, the tale of a boy and his family cow. Petrov revised the source material and made it his own: a spare, haunting, enigmatic tragedy. And he illustrated it in the style of his favorite painters — most noticeably Rembrandt. At a time when animators often used lines to define shapes, Petrov did it with light. He brought the logic of canvas painting to animation.

He’d fallen in love with paint on glass a few years before. It happened on Welcome! (1986), a Dr. Seuss film. Petrov didn’t direct it, but he did art direct it, and he clicked with this style of animation along the way. As he said:

I was the designer, and we were looking for a technique suitable for this subject. We had to find a method that would be less laborious, but at the same time had good image quality. We tried everything in the world... and then one day I decided to paint with my fingers. I just took oil paints and made some sketches right in front of the camera. The image turned out to be very malleable, and everything worked out — it was a real discovery! There was no “epiphany” or “lightning strike” — everything happened in an evolutionary way. Since then I have been working like this. For me it is comfortable.3

Welcome! is a good film; The Cow is a stunning one. And it was a student project, made for Petrov’s post-graduate courses in Moscow. He did the work at an animation studio in Yekaterinburg, stealing whatever hours he could in the evening and traveling back and forth. It took him around two years.

The Cow was Petrov’s first Oscar nomination — and the first for a Soviet Russian animator. He felt an “ecstatic anxiety” as he waited in his seat at the ceremony, convinced that his film would win. “I remember I was shaking badly,” he said.

But it lost to a short from Germany. He was devastated: “I went to the counter and drank vodka,” he said. While he found this funny in hindsight, it felt in the moment like the end of his career. “There was bitter disappointment,” he recalled, “as with a child who was promised a doll but given boots.”4

Ultimately, Petrov got on his feet again. And he finally undertook the film for which he’d gone back to school in the first place: The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1992).5

He’d grown attached to Dostoevsky’s work in college, and this story had stayed with him. It follows a desperate man who dreams about a world without evil, which he corrupts by mistake. When Petrov animated it, he did so with ambitions.

The Dream of a Ridiculous Man is twice the length of The Cow — and grander, more surreal, at times Bosch-like. “[A]ll of my favorite painters, they are all there,” he said. “You can probably guess Rembrandt. You can see Goya; you can see Bruegel.” The result: a beautiful, emotional film. Another two years went into it.

As a graduate student, Petrov had learned from the icons Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog) and Fyodor Khitruk (Winnie-the-Pooh). A word of advice from Norstein stuck in his mind as he worked on The Dream: “you have to match the degree of torment of the author you’re getting involved with.”

Petrov had mixed feelings about whether he’d succeeded. As he later said:

I can’t say that I become smarter with each film. Maybe the opposite. It seemed to me when I was doing Dostoevsky that I was trying to resolve the same questions he posed, trying to live them through again ... It seemed to me that by making this film I would become a consummate sage, and I would no longer have to do anything; I could simply rest on some level of knowledge, wisdom. In reality, this was a childish delusion. I genuinely tried to go through, to match the intensity of thought embedded in Dostoevsky’s story. I sincerely tried to make a work adequate in tone, in power of intensity. But I can’t say that I answered all the questions. I didn’t answer anything at all, probably. I was simply happy that I did it, although painfully and with difficulty, always at the edge of failure, at the edge of despair — what had I gotten into? Nevertheless, the film was made.6

Shortly before The Dream came out, in late 1991, the Soviet Union fell. With it fell the infrastructure for animators. It was a difficult time — for Petrov especially. The reason was that, amid the economic collapse, he, his wife Natalia and their son Dmitry moved to Yaroslavl (Petrov’s birthplace) in hopes of starting a new animation studio.

This proved disastrous. “When I arrived in Yaroslavl, it was an absolute failure: no place to work, no money to make a film, no materials, no equipment,” Petrov said. He became a book illustrator; his wife, a shuttle trader who flipped goods between Russia and Poland. It was her work, he said, that made it possible to build something.7

A local film club gave him a tiny room for free. His family saved up money to supply it. Among other things, Petrov bought a camera, whose sellers in Moscow scammed him (they didn’t include a motor). That meant even more work.

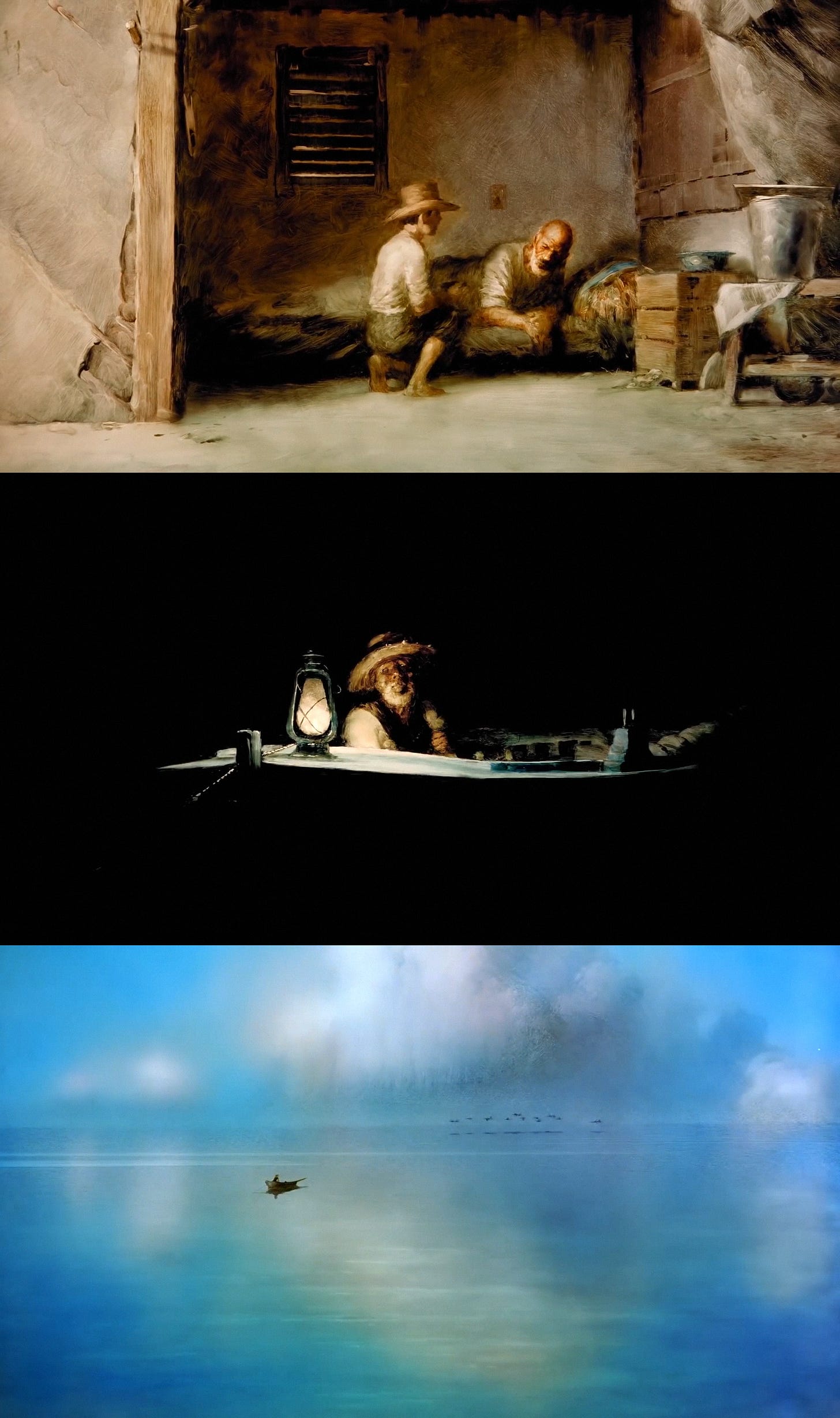

It took roughly three years to get things going, but it led to The Mermaid (1996), another Oscar nominee. Petrov has called it his favorite of his films.8

The Mermaid isn’t strictly an adaptation — the idea emerged from an exercise in Petrov’s post-graduate studies. Students had to pick a famous short story and storyboard three versions with different tones (melodrama, comedy, tragedy). Petrov’s choice was Poor Liza, about a peasant girl betrayed by a rich man. Coming across his storyboard again in the ‘90s, he submitted it for state funding. It was approved.

To understand The Mermaid, it’s important to know that its original title is Rusalka, and a rusalka isn’t exactly a mermaid. It’s more of a river siren, born from the spirit of a young woman who drowned nearby. This is the core of The Mermaid’s plot: a tale of betrayal, guilt and retribution. The wrongs of an old monk come back to haunt him.

Visually, Petrov looked to Rembrandt again, alongside the Russian painters Valentin Serov and Mikhail Nesterov. Although he worked with “primitive equipment,” his paint-on-glass technique shined. He shot documentary footage during the film’s creation to show its process. As he explained:

The paints that my method uses are regular oil paints which can be bought at any store. The only thing is that I pick out “transparent” paints; those are the paints which can transmit light through their layer. They are also called “glaze” paints. Why? Because body-color paints, or parget, don’t let light through; they only reflect it, and this doesn’t suit my method because I work with lamps that shine up from below, through the image.

The Mermaid was Petrov’s most agonizing project — and his struggle with its ending brought him close to abandoning animation. But he got through it. The year he spent on the production didn’t go to waste.9

Petrov and his family were going through troubled times, but the films were succeeding. There were awards from Russia, Canada, India and Japan — some with good prize money. People around the world were fascinated by his work.

In the mid-1990s, this fascination brought about The Old Man and the Sea (1999). It was billed as Petrov’s first “commercial film,” with a budget above $2 million. Fans of The Cow had reached out from Canada and set him up in a studio there. Major backers from Japan got involved. Between 1997 and 1999, Petrov shot the film in IMAX with state-of-the-art gear. He won an Oscar.

We’ve told that story. Petrov had finally made it — the Oscar caught the attention of people in power, and he got to create a real studio in Yaroslavl at last.10 Yet there were problems, too.

Petrov’s style has always sparked controversy. After an early screening of The Cow, one festival judge refused to accept it as an animated film — another called it “a kind of fake animation.” The Old Man and the Sea was on a different scale, though. The head of the Ottawa Animation Festival dismissed it as “kitsch.” Opinions in Russia weren’t the best, either. Khitruk and Norstein, too, preferred The Cow.11

Petrov didn’t necessarily disagree. “I think The Cow is better — for its emotional, psychological component,” he’s said. The Old Man and the Sea is a rousing spectacle, but its story doesn’t cut as deep as Hemingway’s original, and Petrov was aware of this.12 In his words:

When you read the text, you feel how painfully the minutes and hours drag on; the night cannot end. Unfortunately, this could not be recreated in the painting: it turned out too poetic.

The Old Man and the Sea is a good film. It made Petrov’s name. This kind of controversy, though, has followed his work since.

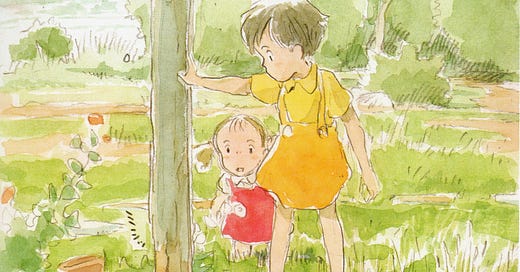

When he made My Love (2006), his longest and latest film, it was headline news. Four years went into it — the project was so large that Petrov had to supervise a team. Japanese backers got involved. Studio Ghibli gave it a theatrical release in Japan (Isao Takahata was effusive). Petrov got his fourth Oscar nomination.13

But the blowback was severe.

My Love is another adaptation of a Russian story, about a teenage boy’s coming of age. Petrov challenged himself to do something a little less depressing. “I am not a cheerful person. I can have fun, and sometimes it brings me joy and pleasure, but when it comes to creativity, my fun disappears,” he said. The lighter tone of My Love was “creative progress” for him.

The painting is lighter, brighter and more colorful, too, and more realistic than ever. Petrov has always had an uncanny ability to capture human figures and movements (he almost never rotoscopes), but My Love takes it to extremes. The results are impressive, but at times more commercial than his past work, and not always as evocative.

This isn’t “Hallmark kitsch” — but the head of Ottawa described it that way. Sharp criticism hit when My Love screened at Russia’s main animation festival, and other filmmakers, in many countries, spoke out against it. “The winning of the kitsch over the art,” wrote animator Theodore Ushev (The Physics of Sorrow).14 Norstein, an artist Petrov regards as a guiding star, was disappointed:

I wished for depth. I wished for... economy. I wished for, on some occasions, humility, when virtuosity gives way to something more deep, psychologically more important.

Petrov has expressed reservations about My Love himself. “[S]ome things really didn’t turn out as I wanted, in terms of animation, in terms of painting, in terms of directing... I have a kind of internal discomfort,” he admitted. The switch to digital shooting, editing and compositing was especially painful.15

It’s not fair to be that hard on My Love, though. This film may not reach the heights of The Cow or The Mermaid, but it’s a worthwhile piece. Seeing it today, it’s clear that the vitriol went way too far.

Petrov hasn’t put out another film since My Love. The 21st century hasn’t drawn a ton of animation out of him in general. Even so, he hasn’t retired — he’s been working on a feature, The Prince, for a number of years. It’s scheduled for 2025.

One final project that needs to be mentioned is one of Petrov’s shortest. It came out a few years before My Love, in a 2003 anthology film called Winter Days. Director Kihachiro Kawamoto called in animation stars from around the world, each one handling a short scene based on a 17th century poem.

Petrov’s section, Tokoku, is around 40 seconds long. It took him four months. Around it appears the work of masters who were much more experienced than himself: Yuri Norstein, Reiko Okuyama, Jacques Drouin, Isao Takahata and more. But Petrov made the list. And he belonged there.16

2 – Newsbits

The Italian animation legend Bruno Bozzetto, now in his mid-80s, is still very active. He and his son spoke to the press about their kids’ series The Game Catchers, their new studio space in Bergamo and more.

In Russia, officials are talking about banning YouTube entirely. (And yet the state-owned Soyuzmultfilm, which lost its YouTube channels in recent months, has returned with a new one.)

Speaking of Soyuzmultfilm and Yuri Norstein, they’re in another dispute in Russia. The studio and the Central Bank have done a commemorative coin dedicated to Hedgehog in the Fog, seemingly without its creators’ approval. “My wife Francheska Yarbusova is the artist of all my films. ... They did not even ask her,” Norstein said.

In America, The Wild Robot is a hit. It led this weekend’s box office with a take of $35 million.

Now on Netflix, the Japanese film Grave of the Fireflies picked up 1.5 million views in its first week.

Aardman of England is involved in the 10th anniversary celebration of Over the Garden Wall, and there’s a teaser.

Data from Ampere Analysis in England shows a 15% drop in streaming commissions for kids’ shows and films (between 2022 and 2023). It also shows that families with kids stay subscribed at higher rates.

In Canada, the Ottawa Animation Festival happened this week. Flow took the top prize among features, following its victories at Annecy. Other winners: I Died in Irpen (Best Script), Scavengers Reign (for animated series) and more. See the full list.

In China, New Weekly offers a deep dive into the challenges of the current animation industry, and the overworked, underpaid artists who power it.

Lastly, on Thursday, we covered the evolution of Katsuhiro Otomo’s filmmaking through his storyboards.

Until next time!

Yuri Norstein and Fyodor Khitruk both praised The Street — Norstein watched it in the early ‘80s (mentioned here), and felt that Petrov had borrowed from her. As for the origins of paint-on-glass animation, Walter Ruttmann used it in Lichtspiel Opus I (1921). For more, see the book Optical Poetry.

See the Los Angeles Times.

From an interview with the Oblastnaya Gazeta. He also discussed the process on Welcome! here.

He discussed his reason for taking the courses with Izvestia and Oren Inform, used throughout.

Sources for the rest of the Dream section: interviews with Film Studies Notes, Nasha Versia, the official portal of Irkutsk and Vinograd.

For details about the struggle in Yaroslavl, see this interview, this one with Cinema Art and the foregoing sources.

Petrov spoke about the problem with the ending in this interview.

See this interview with TASS.

His line about The Cow being better is from Neskuchny Sad.

Details from here, here and the Ghibli site for My Love.

For the Hallmark line and the quote from Ushev, see this archived blog post. Details about the criticism in Russia come from this article. Petrov cited Norstein as his defining influence in Cinema Art (September 1997). Later, he added Frédéric Back to that list.

He spoke about the problem with computers in this interview.

His work is so beautiful. Thank you fir sharing his story. I was unaware of his work until I read this. It's hard to believe why some critics in his day couldn't consider this as animation. Like the previous commenter said. His work us mesmerising

This is a great, thorough piece. I've been meaning to go through Petrov's work for years, and now I have my chance to watch all of it. It's too bad that so far as I can tell there's no blu-ray collection of all of his works available.