Happy Sunday! We’re here with another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is what we’re doing today:

1️⃣ On the marvel and controversy of The Old Man and the Sea (1999).

2️⃣ Animation news from around the world.

3️⃣ The last word.

New here? It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — get them right in your inbox, weekly:

With that, we’re off!

1: Going big

The Old Man and the Sea is one of those enduring films. Once you’ve seen it, the images stick with you. It wowed people when it debuted in 1999. Still today, almost a quarter-century later, the film is spectacular — literally.

That is to say: The Old Man and the Sea is a massive, enveloping spectacle. The visuals are so rich, you lose yourself in them.

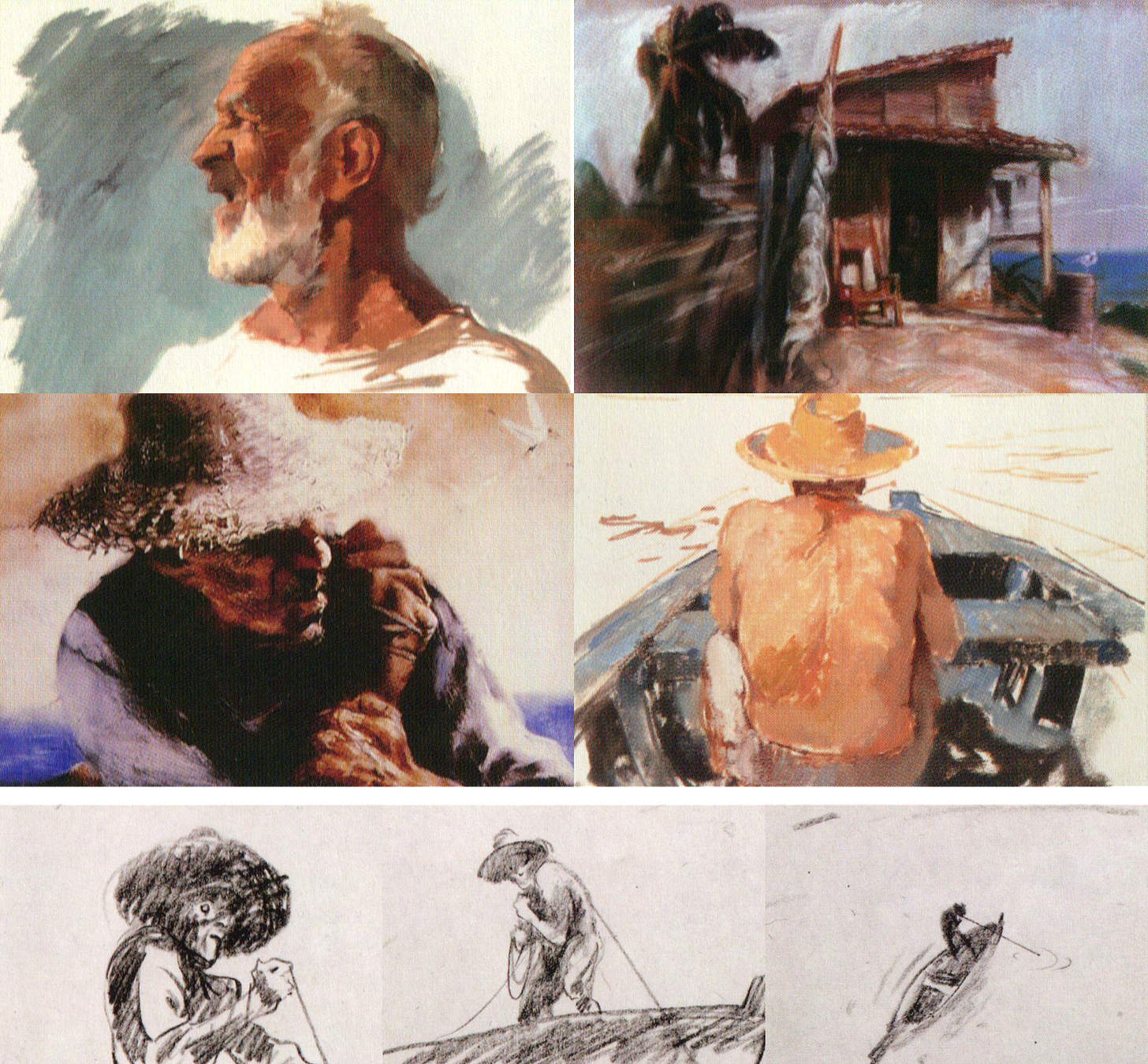

The film is based on Ernest Hemingway’s 1952 novella of the same name — the tale of an old, unlucky fisherman in Cuba, who goes out to sea to find his “big fish.” He gets locked in a battle with nature. Director Alexander Petrov chose to animate Hemingway’s book with the rarely-used paint-on-glass method. He worked on glass sheets with oil paint, which he painstakingly brought to life for 29,000 frames.1

Petrov is the grandmaster of paint-on-glass animation. In The Old Man and the Sea, he went bigger than ever before. He made the film for IMAX theaters: a six-story oil painting in motion; an all-encompassing visual experience of ocean and sky. Even the story takes a back seat to Petrov’s images.

Again, this film (watchable below) is about the spectacle — and it’s a gorgeous one. The ambition and technical fireworks of it all helped to make the film a hit. In 2000, Petrov won a historic Oscar in the animation category for his work here.

Today, The Old Man and the Sea is considered a classic. At the time, though, a debate swirled around it. Many loved the film, but some wondered: had Petrov gone too big?

Born in a small village in 1957, Alexander Petrov started animating in the Soviet Union, having trained under greats like Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog). In 1989, Petrov debuted his first masterpiece — the heartbreaking paint-on-glass work The Cow. Norstein called it “an immediate phenomenon.”

The Cow touched viewers inside and outside the USSR. It was an Oscar nominee in 1990. When it screened in Canada that year, a local animation-studio owner named Pascal Blais saw it. He remembered:

I fell off my seat […] It was unbelievable the amount of work there. It was like seeing a Rembrandt come to life.

It was Blais’s company that would ultimately produce The Old Man and the Sea. But that was a few years away. Back then, the film was just a storyboard that Petrov was sitting on, having failed with it in the USSR. He noted that “there was no producer who would agree to finance this project.”

Things changed thanks to another Canadian at that fateful screening of The Cow in 1990. It was producer Martine Chartrand, who decided that she had to learn how to animate like Petrov. As the USSR disappeared, she traveled to his studio.

Here’s how Petrov recalled it:

She began an apprenticeship to learn the technique of painting on glass, wanting to do something similar to my animation. She and I became very good friends, and she invited me to Canada. She read the script for The Old Man and the Sea and offered to take it with us — in Canada, she said, surely someone would be interested in it. I showed the script to five or six Canadian producers. They all liked it very much, but no one could find the money to produce this complicated, purely auteur work. So I came back […] And a year later a Canadian producer called me to say they had found the money for the movie.

The people at Productions Pascal Blais had landed backers — in Japan. Three companies there liked the idea of adapting Hemingway with Petrov at the helm. (The Cow had won a major award in Japan.) But there was a catch: they would only fund The Old Man and the Sea if it was shot in IMAX.

At that time, in the mid-1990s, a whole animated film in IMAX was a new idea. It had reportedly never been done. “The cost of making it was of course far higher,” Petrov later said, “but Hemingway’s short story is so well known that the potential audience was very large. And, of course, the wide open sea goes well with large formats.”

Even so, Petrov “categorically refused” to do it. He’d watched nature documentaries in IMAX, and he felt that 70 mm film was too big for animation — it would reveal every blemish in his art.

What changed his mind was a short test. He saw his own work blown up in a domed IMAX theater, and it made him think of Michelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine Chapel. “I am no Michelangelo,” Petrov clarified, “but when I see what has become of the small image I have drawn, I say, whoa!”

Until The Old Man and the Sea, Petrov was basically an artist’s artist. The Cow, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1992) and The Mermaid (1996) are beautiful films, but they’re non-commercial. This was all dark, intimate work for the festival circuit. Now, he’d found himself in a new position.

“This is the first time Petrov has worked on a commercial film,” reported Imagica, one of the three Japanese companies backing the project. The budget for The Old Man and the Sea was “an extravagant $2.2 million,” per The New York Times. And, although Petrov painted on glass for art’s sake, the official site for this film pitched the technique as “an instrumental tool for the large format theaters to use to attract new audiences.”

The Old Man and the Sea had become a film somewhere between the auteur piece Petrov had planned and something bigger, more pop. The decision to use IMAX was game-changing. Asked about the technical side of the film, producer Bernard Lajoie said, “Everything was based on the contractual obligation to use the IMAX format.”

That included Petrov’s painting process. The team spent six months and a large sum of money to design a new, roughly 1,500-pound animation stand. It was integrated with computers, and it allowed Petrov to easily paint the background images on a separate sheet of glass, below the sheet with the characters.

Petrov had long preferred to finger paint. He did use tools like brushes, but the core act was direct touch. “The hand, the palm and practically all of the fingers,” he said in a documentary about his method. He made complete images, then adjusted the slow-drying oil paints ever so slightly, photographing as he went. Yet even his finger painting process had to change this time

Here, Petrov moved paint with his hands, but he had to apply it with other tools. The giant images, he explained, took too long to make. On earlier films, his paintings had been 9–12 inches across. Now, he worked at 30–40 inches and above, so that the pictures held up in IMAX. Lajoie said that “there was a risk when broadening the field that you could see his enlarged fingerprints.”

What Petrov painted changed as well. He had to widen his compositions, beyond the main actions of the story, to fill out the 70 mm film frame. Conveying small spaces was hard — the fisherman’s little hut felt enormous in IMAX, Petrov said. Close-ups were out (“they cause discomfort to the viewer”) and bold, vast shots of the natural world were in. As Petrov admitted:

… I had to make some scenes (I’m not saying they turned out unsuccessfully) too spectacular. There were scenes that had to be made spectacular. This was dictated by the screen itself — or rather, not even the screen itself, but the reputation of the theaters, which are designed to shock. These theaters show films such as those where helicopters dive into an abyss or a herd of ten thousand antelopes rushes across Africa. […] And I had to make them. Maybe they wouldn’t have existed if there hadn’t been American, not just taste, but tradition that had to be taken into account.

The Old Man and the Sea was a big production. The credits reveal scores of people involved, all around the world. Petrov even needed a hand with the animation (getting it from his son, Dmitri). He called his camera assistant, Sergei Rechetnikov, “indispensable.”

With their help, and the help of the wider team, around 50 seconds of animation could be finished each month. These were 10-to-12-hour days, with just one day off per week. Everyone’s careful work meant that 85% of the shots were usable without retakes. The filming process started around March 1997 and ended in early 1999 — the least painful, said Pascal Blais, of any film he’d produced:

This one is the most difficult film we have ever undertaken and it was the one that went the most smoothly. I have never had so much respect for one individual as I have for Alexander Petrov. He had the pressure of the whole film on his shoulders. At the worst moments, he never lost his cool or his nice manners. We ended up the best of friends, which is very rare in this business.

As he filmed, Petrov sought feedback from one of his own idols: Canada’s Frédéric Back, creator of The Man Who Planted Trees (1987). Petrov called that film an exemplar “of how an animator, an artist, should think.” It was Back’s idea to add the green glow of the plankton during the night scene later in the film. The composers of The Man Who Planted Trees worked on the score for The Old Man and the Sea, too.

Yet, while Back’s Oscar winner had been greeted with open arms by the animation community, Petrov’s fared a little differently.

Petrov won awards on the festival circuit, praise from many outlets and mainstream attention. His film premiered at a new IMAX theater in London, with Prince Charles in attendance. “In Montreal, some 50,000 spectators have seen the film,” reported Animation World Network in early 2000, “while in Paris somewhere between 60–70,000 [have].”

From some quarters, though, there were insinuations that Petrov had sold out. That he’d dumbed down Hemingway’s story, gotten swept up in his own spectacle.

This happened even back home in Russia, where The Old Man and the Sea was a lightning rod. “It’s been a long time since I can remember an animated film being so controversial and of such heightened interest,” noted a writer in one Russian film magazine. Praise and criticism came together. When Petrov won a few of Russia’s Goldfish Awards in 1999, his old teacher Yuri Norstein was on the jury and reportedly said of his film: “skill and craft — these are not everything.”2

Even after Petrov’s Oscar win (the first for a Russian animator), the press, public and professionals in Russia were divided. The newspaper Kommersant noted that applause for his film was muted at the Moscow Film Festival. It was shown in 35 mm, losing the IMAX effect, but the writer argued that Petrov was in fact “not forgiven [by the audience] for the purely American simplicity” of his handling of Hemingway.

Some American specialist outlets shared that hostility. “Petrov’s interpretation [of Hemingway] becomes congested and ultimately superficial,” read one article in AWN, which dismissed The Old Man and the Sea as more like “a Hollywood studio epic than an independent personal vision.”

It was polarizing. The kind of film that could win the Oscar and the top prize at Annecy in France — but get snubbed at Canada’s own Ottawa Animation Festival, the same event that had screened The Cow back in 1990. “Unfortunately,” wrote Ottawa’s director about The Old Man and the Sea years later, “neither my colleagues nor I felt the film was that good.”

But how fair was the criticism, really?

There’s no doubt that, in Petrov’s version of The Old Man and the Sea, the character of the fisherman is fainter. You aren’t as invested in his personal feelings, his highs and lows. And it’s true that the film lacks the down-to-earth realism of the original — the grime, the gritty sense of struggle, the endless little descriptions of the natural world and the work of fishing. Take this paragraph from Hemingway’s story:

He knelt down and found the tuna under the stern with the gaff and drew it toward him keeping it clear of the coiled lines. Holding the line with his left shoulder again, and bracing on his left hand and arm, he took the tuna off the gaff hook and put the gaff back in place. He put one knee on the fish and cut strips of dark red meat longitudinally from the back of the head to the tail.

This simply isn’t the focus of Petrov’s film. Moments like these demand close-ups and a thousand subtle movements, but the IMAX format keeps us at a distance. The film is more interested in rippling waves, vibrant clouds, birds in flight. Even the fisherman’s struggle against nature is often beautified. When he pulls the line with his full weight, it looks painterly, but not in the harsh modernist strokes implied by Hemingway’s words. And his gashed hands are mostly hidden from us.

A few years after the premiere, Petrov acknowledged himself that he’d drifted from the Hemingway text and made something else. As he told a journalist in 2002:

It seems to me that the scenery is especially successful in my film. I realized from the critics’ reviews that the story of a man’s struggle for his fate has gone into the background, and what remains is a spellbinding world that acts even stronger than the character, than the story. It pleases me because I was trying to create something interesting, to make a convincing, living sea.

Over two decades later, it’s hard to argue with that. The Old Man and the Sea may not be totally faithful to the story, but it wasn’t really made to be, and it doesn’t really need to be. This piece has its own identity, despite the compromises Petrov felt he was making along the way. The “wow” factor is still there. Even when you’re watching it on YouTube rather than in an IMAX theater, it still hits in 2023.

And it may not hit strictly as a narrative (although there are standout narrative moments, like the fisherman’s haggard expression after killing his fish). It’s a visual piece first and foremost. A gigantic, virtuosic visual piece. That’s not just skill and craft, as Norstein put it — Petrov isn’t simply showing off. He’s expressing something about nature and art, even if the things he’s expressing don’t all match the original.

As the years have passed, and the controversies have receded, The Old Man and the Sea has stayed right where it is. The scale of its achievement is too large to fade away. This is one of those enduring films. It may not be perfect — but, once you’ve seen it, the images stick with you. The spectacle is tremendous.

2: Newsbits

American studio DreamWorks has made its MoonRay renderer, used for films like the new Puss in Boots, available to the public as free and open-source software.

If you happened to miss the Japanese film Princess Arete last year when it was free on YouTube (with English subtitles), it’s back for a limited time. We love this one.

Chinese historian Fu Guangchao is doing more groundbreaking work on the classics of Shanghai Animation Film Studio. His new lecture series explores the team’s process for Uproar in Heaven, identifying the animators of specific shots and analyzing their techniques. He compares it to The Illusion of Life for China, and is already sharing rare images.

In France, Annecy has revealed its short film selections for 2023, and they include the long-awaited debut of a short by John Musker (of Disney fame).

Another from China: the popular and widely criticized series The Three-Body Problem has beaten 500 million views on Bilibili. The controversy over the show’s visuals and story continues to rage, but viewers keep watching.

In Chile, the Cineteca Nacional shared a short video about the process of restoring La transmisión del mando supremo (1921), the first work of Chilean animation. It was rediscovered in January after decades as a lost film.

A shakeup in British animation. The government is moving to reform its support for animation by offering “money ahead of their production as opposed to being able to claim it back after it has been spent on the production,” per Skwigly.

Data shows that Soyuzmultfilm was Russia’s top-earning animation studio in 2022, defeating even the Riki Group.

Ireland’s Animation Dingle is coming up on March 24. Many festivals have gone back to a strict in-person format, but this one offers quite a bit to virtual attendees as well.

Lastly, we looked into a trio of animated music videos from Japan: Dore Dore Song by Studio Ghibli, Jubilee by Koji Yamamura and GAL-O Sengen by AC-bu.

3: Last word

That’s a wrap for today’s issue! Thanks for checking it out — we hope you’ve enjoyed.

One last thing before we go. In the March issue of his popular newsletter, author Robin Sloan shouted us out again. He’s had very kind things to say about our work in the past — we’ve been honored. That goes doubly for his latest comment, in response to our 2022 piece on the Japanese film Invisible:

… Animation Obsessive is doing something really special; in its depth, it more powerfully evokes a gloriously niche print magazine than any other newsletter I receive. If you’re interested in global animation — past, present, and future — you really ought to be reading, and perhaps paying for a subscription, too.

[Animation Obsessive]’s discussion of the anime short Invisible was wonderful; I’m grateful to have learned about this mesmerizing work. I strongly recommend first reading that newsletter, then watching the short here.

Our thanks to Sloan for these wonderful words. You can check out his March issue here — he offers some fascinating insights into the writing of The Lord of the Rings.

Until next time!

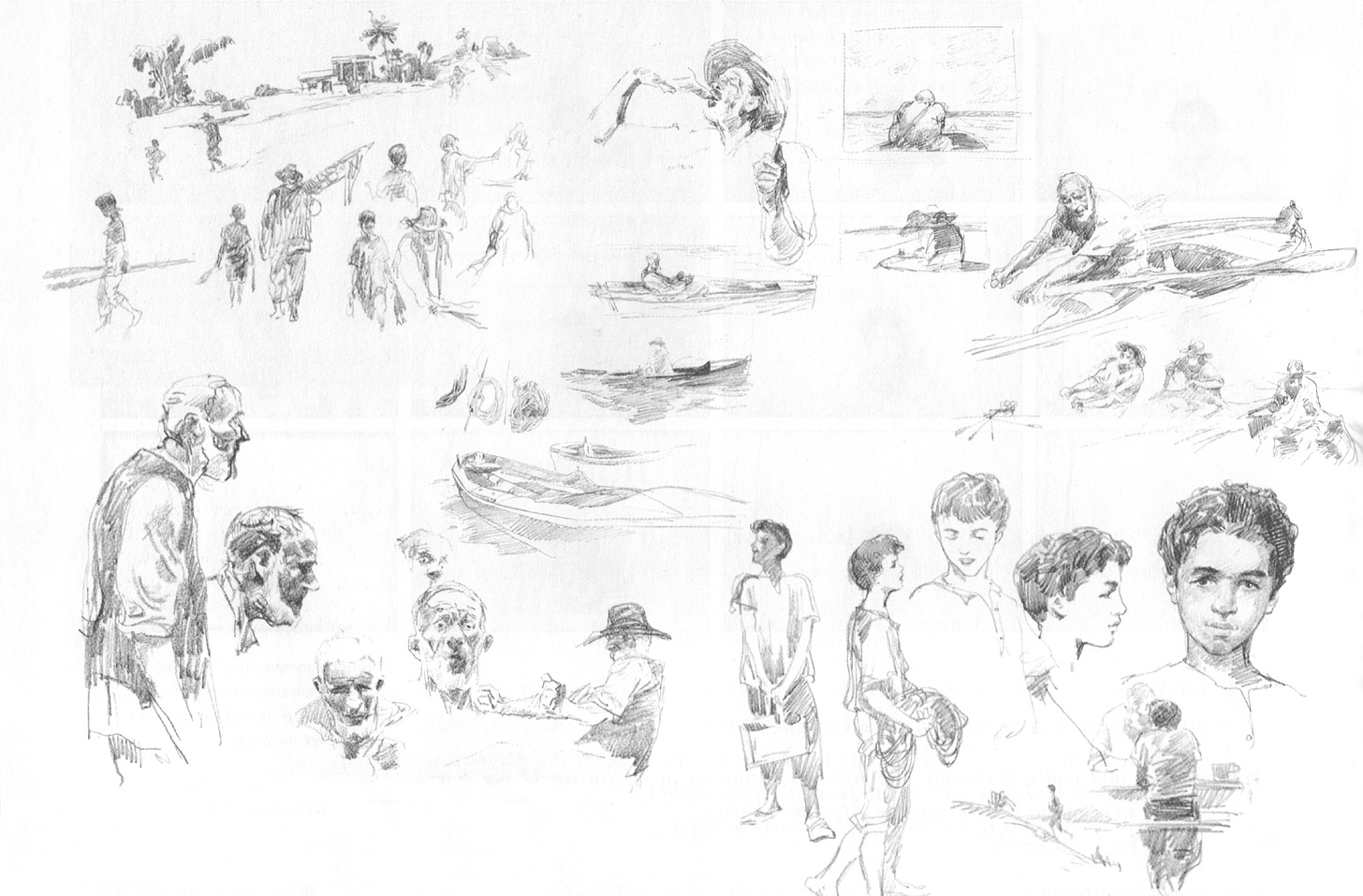

From the book Secrets of Oscar-Winning Animation, one of our key sources today.

Norstein jabbed more at Petrov’s films later, when he questioned My Love (2006) in an interview. It’s worth noting that Norstein’s own senior, the late Leonid Shvartsman, strongly praised Petrov’s work (including The Old Man and the Sea) in 2020.

Love the style this is written in. Always informative and personal yet highly researched. Thank you.

I just read the book. I think it's fascinating how art can create other art, and your article delves into that idea very thoughtfully.