Pivoting and Making It Work

Unearthing a classic MTV short, plus a new music video, plus news.

Welcome! It’s time for another Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is our lineup:

1) Uncovering the story of The Big City by Ed Bell.

2) A rich music video by a first-time animator (and more news).

One tidbit before we start — check out this before-and-after comparison of an animation drawing from Sleeping Beauty. It comes from the blog of Disney legend Andreas Deja, who has intriguing thoughts on the changes between the two.

With that, here we go!

1 – Outside the box

The series hit the air in 1991. It ran on MTV, and its title referenced a weird idea that Salvador Dalí liked to talk about: Liquid Television. Dalí’s version was a “liquid, from a bottle, [that you put] on your hands, your nose, your clothes” to display TV images.1

MTV’s version was only a little less ambitious. It settled for being one of the strangest television shows ever made.

Liquid Television was an animated, or mostly animated, anthology. Each episode was a jumble of skits — all of them were random lengths and styles, and none of them really fit together. The show’s creator said that even he didn’t like everything it ran. (“The idea is the attitude,” he argued.)

But Liquid Television still had its hits: Aeon Flux and Mike Judge both broke out through this thing. Everyone who’s watched it has a favorite segment.

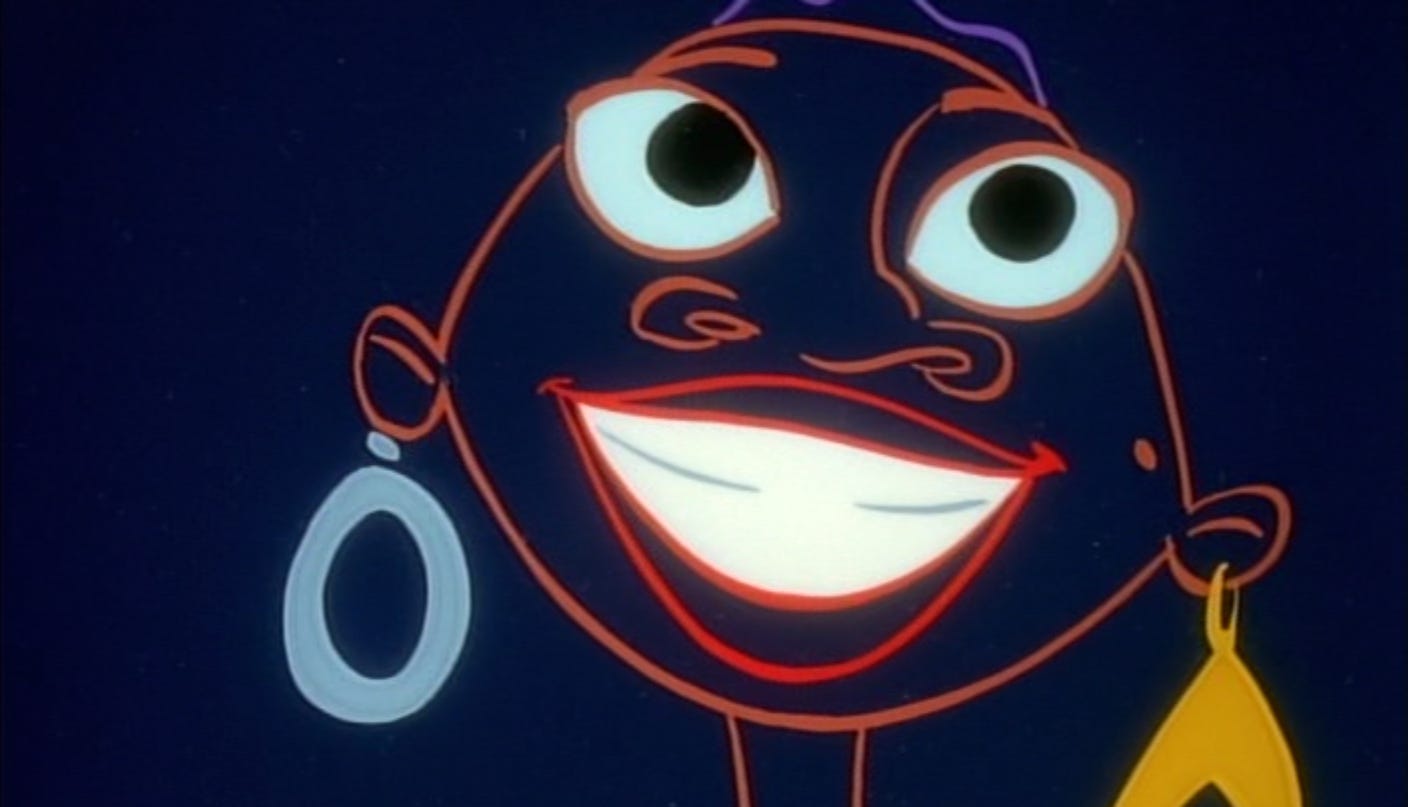

For us, it’s The Big City, a one-off short that Liquid Television aired in 1995. It’s about a woman named Nola Kambanda who leaves Ghana for New York City. She wants to join the fashion industry — but she encounters a different America than the one she imagined. Her five-minute story is a stylish musical.2 It’s rap-narrated, animated in a neo-UPA way and drawn primarily in bold, neon lines.

We’ve wondered for a while how The Big City came to be. Its director Ed Bell is still active — he’s a veteran today, with credits ranging from Roger Rabbit to Bebe’s Kids (1992) to Pixar’s Soul. Last month, we spoke to him to learn the secrets of this film.

We’re happy to bring you those secrets today, and to (re)introduce The Big City almost 30 years after its premiere.

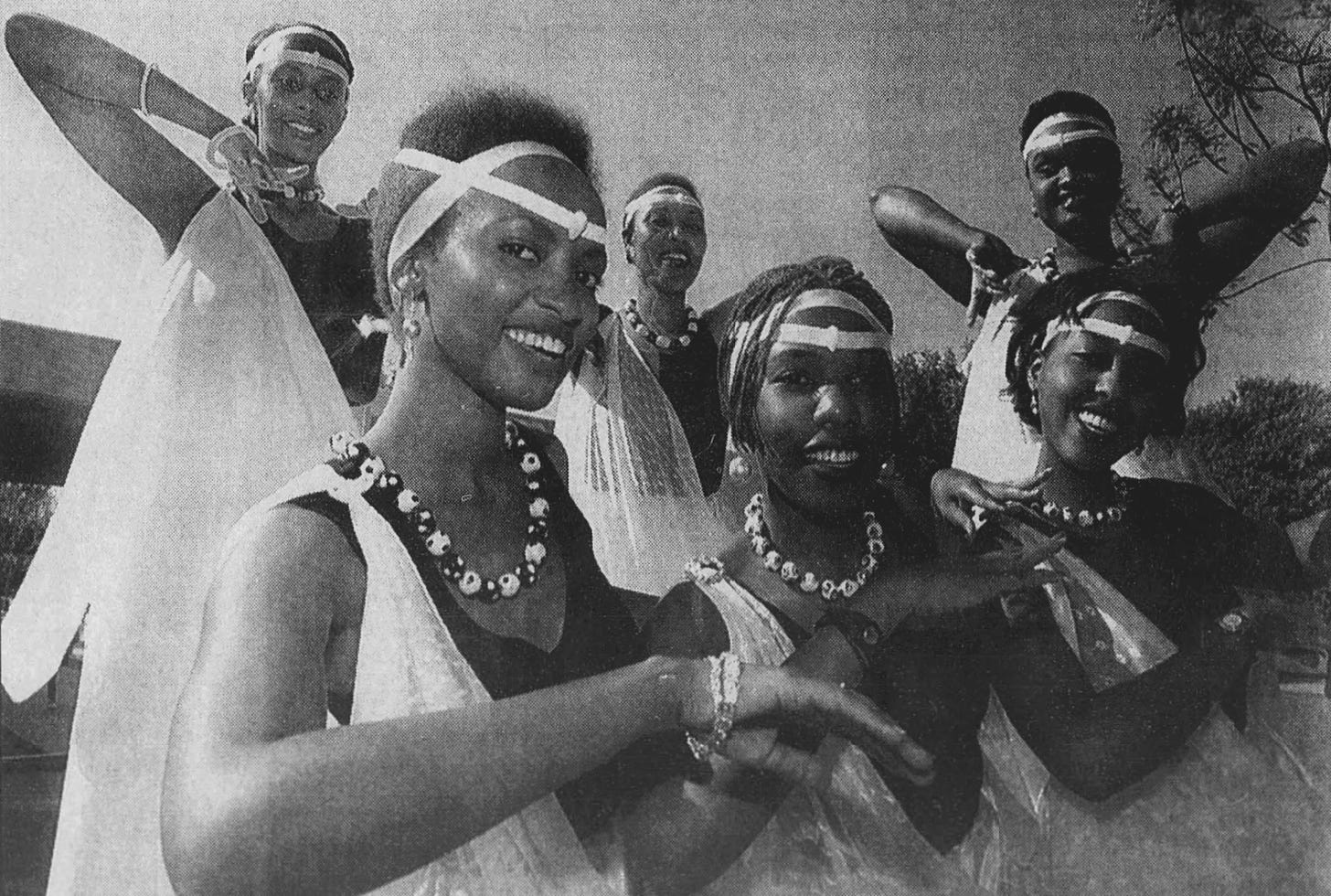

For Ed Bell, The Big City was a confluence of a lot of different threads. It was a personal project — each part of it tied back to life. As it turns out, there’s a real Nola Kambanda. Bell had known her for several years.

“She was a friend of mine who I’d met a few years earlier, who was from Rwanda,” he says. “And her background was very much a piece of that time period.”

The real Kambanda was a Rwandan born in Burundi — a Tutsi. At school in the small town of Kiganda, her name turned up on a hit list written by her fellow Hutu students. The horrific events of 1994 were in the future, but Kambanda was still at risk as a member of the Tutsi minority. Ultimately, she fled to Los Angeles, taken in by a family her parents knew.3

That’s where Bell (“a nerdy kid from South Central LA,” as he puts it) met her. He had ties to the activism happening in the area. Like he says:

My church at the time — a lot of the churches in LA, the African Methodist Church, the Baptist churches, a lot of different denominations were inviting refugees … she was part of that whole program, coming in and getting a certain diplomatic status. And then I think she had to earn her citizenship over the next five years or so. I was just getting to know her when she was at the start of her journey.

Quickly, Kambanda fit in. “Even though she came here on a weird, dark note, she ended up being the light of everybody’s life around us,” Bell says. She was popular and a brilliant student, and she kept getting offers to model. Later, she joined Boeing and worked on the Space Shuttle program for NASA.

Bell still laughs at how wild that sounds: “I mean, it was a joke in my time — the model who’s also a rocket scientist.” But it was true. And her life story, as an outsider breaking into show business, mirrored Bell’s own in key ways.

It was something they talked about. Bell remembers that Kambanda got “all these revelations about media” after going from outsider to insider. She told him “how very human but very dumb ... the modeling industry was, with the things they asked you to do and the reasons they would ask you to do them.” As someone with a budding Hollywood career, he was experiencing his own insider problems.

All of those thoughts fed into The Big City.

Bell was on the rise when the opportunity came. He’d graduated from CalArts in the late ‘80s and gotten a job on Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures. He kept learning and growing from there. Eventually he moved to San Francisco, joining Colossal Pictures in 1992.4 The studio happened to be in the middle of producing Liquid Television.

As he says:

I was just starting out at Colossal when I found out about the whole Liquid Television thing. It was this program that college kids and potheads really loved. It was very outside the box — it was basically the ‘90s version of Adult Swim.

Liquid Television was hungry for fresh material. Pitches and ideas from around Colossal were its fuel — and Colossal was “a pretty diverse place.”

Bell explains, “In LA, I was used to being the only Black guy in the studio [laughs], around the work pool. Or one of two, out of a crew of 300. When I got to Colossal, San Francisco was pretty different.” And Colossal’s series became an outlet for stories that other studios weren’t telling.5

After getting involved in Liquid Television through someone else’s segment, Bell pitched his own — drawing on his personal experiences. It was a metaphor for what he and his friends were going through, as young people who’d entered a big, unpredictable new world that wasn’t always ideal.

“Since they were so open to ideas that hadn’t been seen before,” he explains, “I just tried to go as outside the box as I could and trap all my thoughts.”

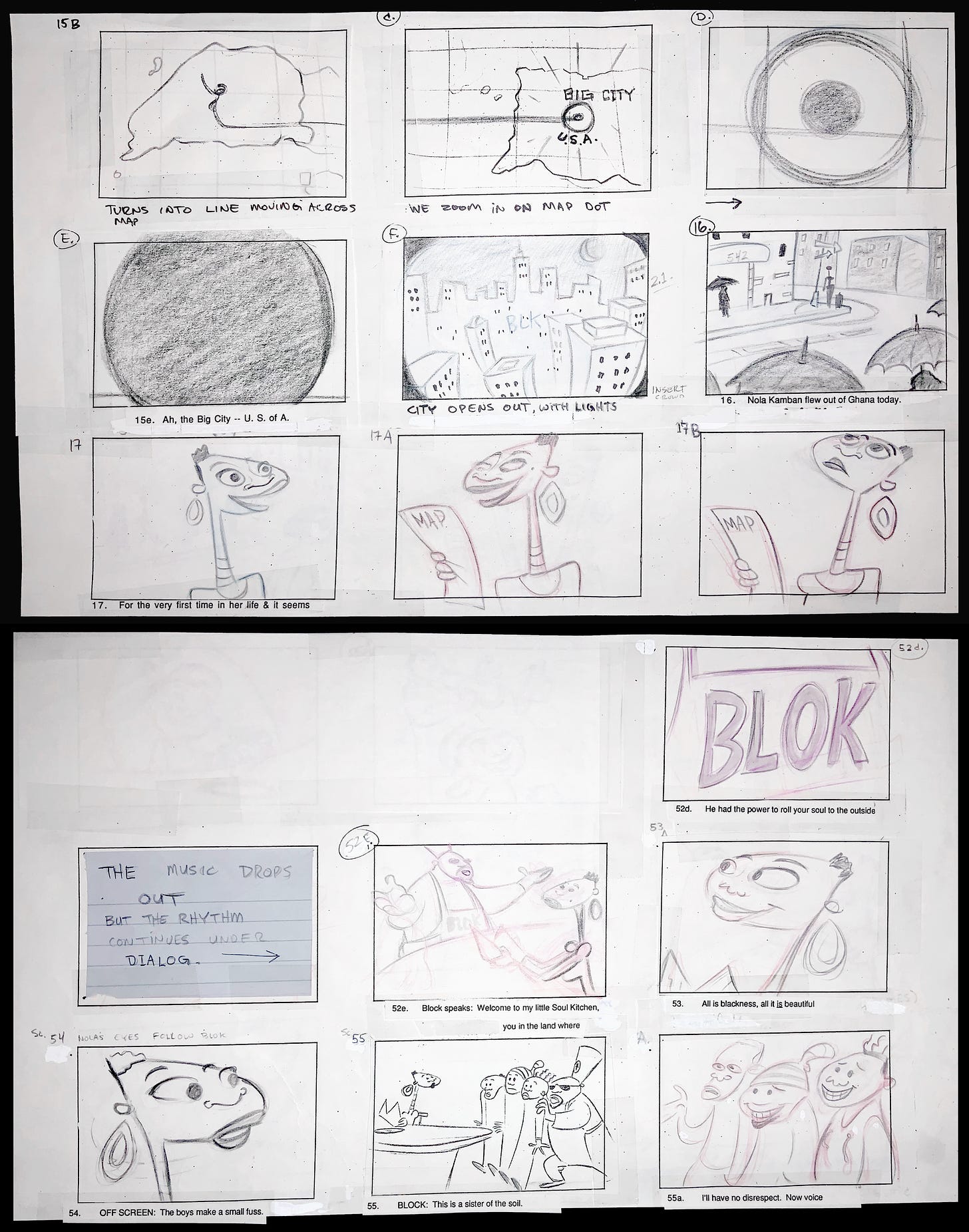

He’s admitted that his pitch was disorganized, but it was accepted anyway.6 And then the making of The Big City had to be crammed into maybe six weeks, including pre-production. Full production was closer to four weeks, as many as 90 hours each. Money was tight, too, as it tended to be for Liquid Television. Bell remembers:

… the budget was super limited. A lot of these things happened that way, where they’d give artists a big opportunity, but they’d have to make do with a little bit. They’d have to figure out what they could do with very little. And that’s part of the test, I guess. It was like, “Okay, this can be your creative thing you’ll have your name on, but we only have about $7,000 for each one of these. And each person gets a fraction. That $7,000 has to break up between each director who gets a show, or gets to do a pilot.” And that was unheard of.

To do The Big City with almost no money, Bell had to use every trick and creative cheat he could find. The idea for rapped narration came about partly for this reason.

He’d created a story outline but didn’t think he could write a great script alone. So, he got help from people he knew: Kevin Wyatt (bassist, producer) and Jason Sugars (rapper). As Bell recalls, it was Sugars who pitched the idea to “either do [the film] as a poem or as rap.” A ton of story needed to be packed into just a few minutes — shorthand and quick transitions were a necessity. Rap storytelling could do both.

At the time, Bell and his friends were into the alternative hip hop scene in Los Angeles. “My whole identity around LA was kind of the backpacker hip hop generation,” he says. While at Colossal, he was making trips back to South Central to catch shows at the famous Good Life Cafe — where acts like The Pharcyde were performing. Sugars himself had gotten noticed in that scene for his abilities.7

The Big City’s music came together fast in their home studio. The real Nola Kambanda showed up to voice a few lines for her character — who’d turned out to be pretty different. Bell even switched the setting to New York, a universal symbol “that everybody in the world could understand, like a big, chaotic place you could get lost in.”

The Big City was never meant to be a documentary. Again: it’s a “metaphor.” It distills complex experiences and feelings into a fun, widely accessible short.

Basically, a mix of personal experience and practical need influenced the music. And the visuals went the same way. Bell calls it a process of “getting really minimalist about the ideas, and how we could make it super spartan and without a lot of bells and whistles, but allude to bells and whistles.”

That’s where the neon-line aesthetic came from. Empty lines were cheaper — there was less for the cel painters to fill in. Bell saved part of his tiny budget by taking from visual styles where “the outline was supreme.” His reference points: a “pastel on black” section from Fantasia, the pink elephants from Dumbo and the chalkboard sequence from Bebe’s Kids that he’d worked on not long before.

For the movement, Bell wanted traditional 2D cartooning, which he’d also done on Bebe’s Kids. “I was really loving that style,” he says. At the same time, the budget made it impossible to use the Roger Rabbit method of full animation, which was his training.

“I kind of had to get rid of my snobbery and see what I could do with limited animation,” says Bell.

It turned into a puzzle — how do you get ideas across with the fewest drawings, the most stylized movement? Studios like UPA had done it decades before. He was following in their footsteps:

I started reading up on [limited animation] and talking to the people I knew who were part of that world. Some of the old men that I knew at the time were, like, Hanna-Barbera artists when they were younger. And I think those folks came up with a lot of the techniques and methods that made up limited animation around the world after that. So I was trying to adapt some of those techniques. There were also people in the studio at Colossal who were great artists, who understood how I could economize ... We gave ourselves these guardrails for the storytelling.

One other influence was his time on Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, a “very limited animation program.” Hollywood vets like Virgil Ross and Maurice Noble had come by the studio to give talks during that project. Bell says that “they had a lot of tricks up their sleeve … to get your point across, to tell a story in one image.”

And so The Big City became a showcase of limited animation done right. Each pose and movement is strong, fun, readable — and minimal. Even as fast as the story goes, the images stay clear. It’s great cartooning in the mid-century style. Yet the film was current, too. “It was fun to do something that was a modern story,” as Bell puts it, “but that was in a style I had seen from a real early time in animation.”

He submitted his storyboard for The Big City in June 1993, and the film hit Liquid Television at the end of its third season, in January 1995. He wasn’t sure what to expect — this was all “a big experiment,” something totally different. There was no way to guess how people would take it.

But the short did well. Speaking to a magazine around the time it aired, maybe Esquire, Bell said that The Big City is a story “all about family, how you gotta have it.”8 The animated Nola Kambanda finds a new home in New York, new friends who care about her. The real one had that experience as well — just on a different coast, in a different context.

With this project, Bell technically made a pilot, and his hope was to develop a series based on the same ideas and “metaphors.” He sent us a photo of one proposal from 1997, Big Slim’s Kitchen, that looks like a later take on it. But no Big City series ever came to be. It didn’t take off like Aeon Flux did.

Almost a third of a century later, we’re left with the standalone short (embedded above). It holds up well. In some ways, it was ahead of its time.

People could tell it was good even back then, though: it went beyond Liquid Television to reach the festival circuit, making it to Annecy and Japan. Bell remembers smoking outside a few festival screenings until his film was over — it was hard to watch the “mistakes.” To viewers seeing it with fresh eyes, those mistakes have never really been visible.

For Bell himself, the biggest takeaway was the experience. Some of his collaborators from Liquid Television (he cites artists Dan McHale and Cindy Ng) kept working with him for years. And he learned a lot.

Looking back, Bell says that The Big City was defined by its limitations — and by the creativity it took to make the most of those limitations. The whole way through, he and the team were trying:

… to creatively save ourselves. Like, “Oh, we can’t do that? ... Well, how are we gonna make this work then?” That kept coming up over and over the four weeks, and so all that problem-solving ended up making you go, “Well, this wasn’t my first idea; this is where I arrived at by trying to make this thing happen.” It was a great lesson, because every production goes south.

Everything I worked on after that, every movie — those productions always have to deal with the unforeseen, and the factors you can’t control for or can’t predict. You’re always pivoting and making it work.

2 – Worldwide animation news

Learning to animate in New York

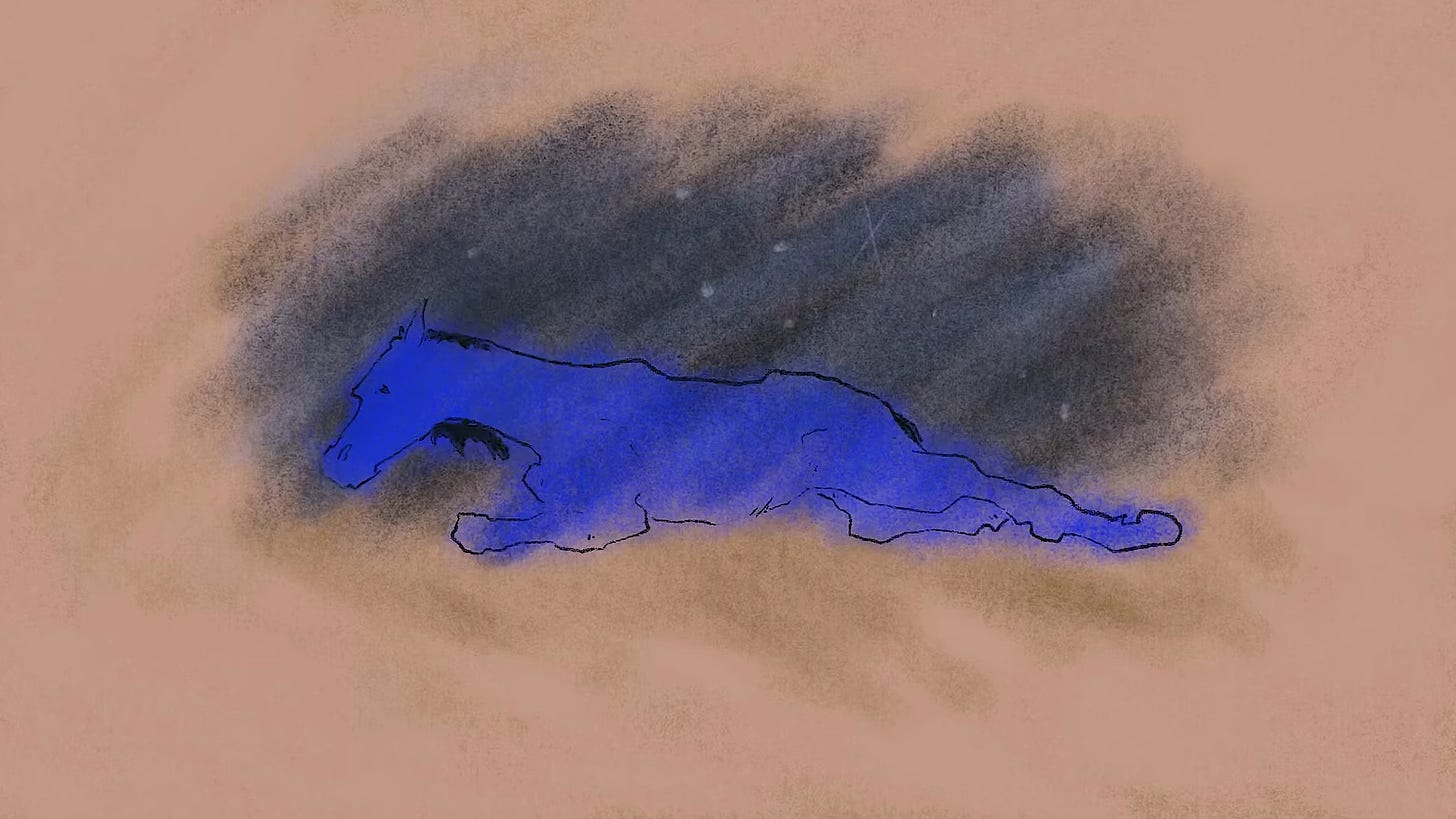

Speaking of songs set to animation — earlier this month, a music video got our attention. It’s for a track called Opus by the indie band Lightning Bug, based in New York City. The visuals are eerie, dreamlike and rich. As it turns out, they came from the hand of a first-time animator.

That would be Dane Hagen (also a member of Lightning Bug). Like frontwoman Audrey Kang tells us, “Dane was completely self-taught and had never animated prior to this video. However, he’s a really talented visual artist who’s been drawing and painting all his life.” The idea for the video was hers. Hagen put it into images.

You could call the result an experiment in learning. “I was really stubborn in not wanting to watch videos on how to animate or watch animated content at all while doing this,” Hagen explains. The goal was to take his personal style of drawing on paper and transfer it to an iPad and Procreate, using a pencil brush from True Grit. He made up the process as he went:

At first, I’d draw every frame sequentially for sometimes 200-plus frames. Literally just one… two… three… and I was like, how do people do this? A couple of months into working on it, and after I took a break for a couple of weeks, I started a shot and it suddenly clicked that I should draw out like 10 important frames and then go back and do drawings in between those frames and more in between those. It sounds so dumb for someone who knows how to animate, but I had to just figure that out through trial and error. So it was mad baby steps.

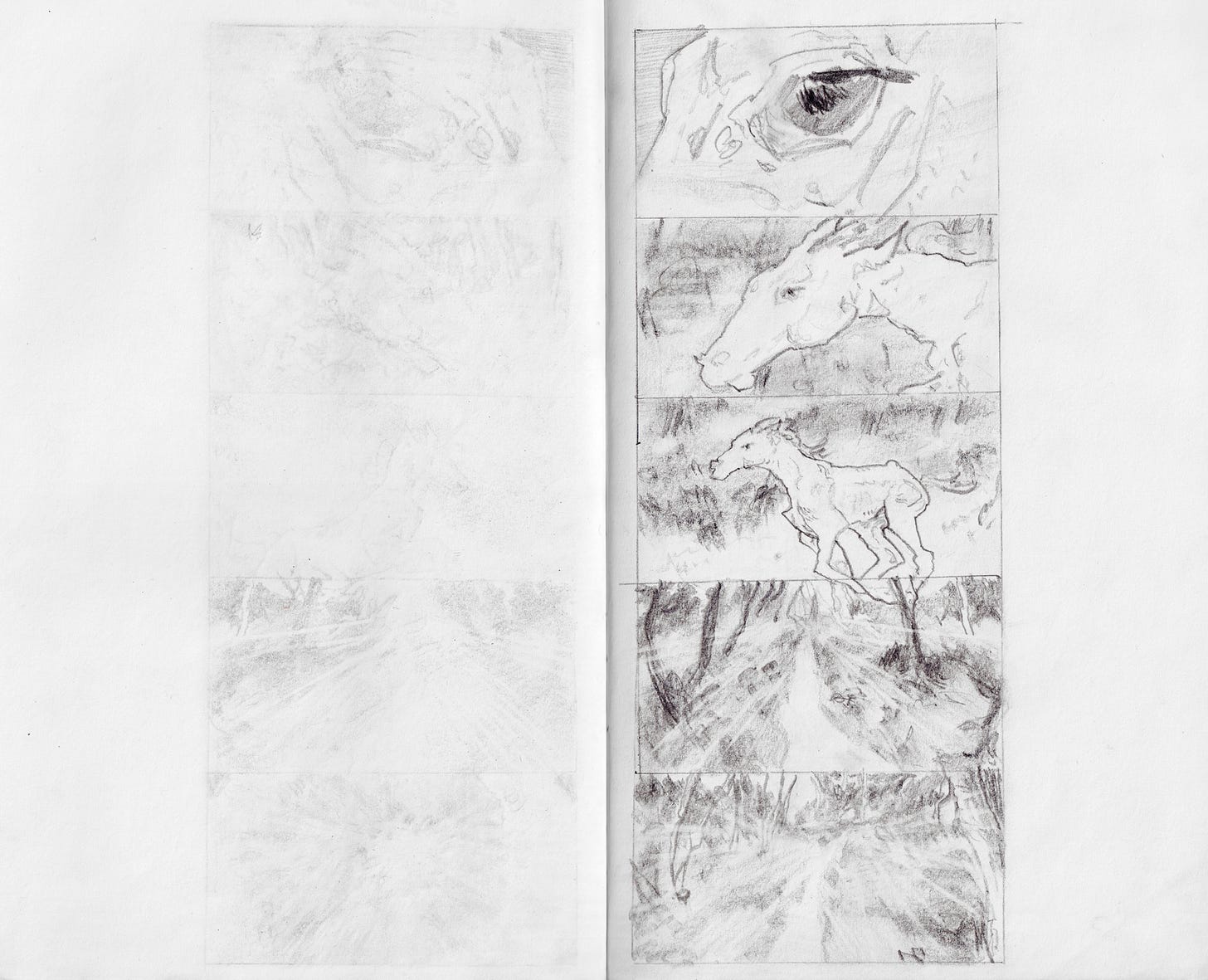

A cool-looking use of rotoscoping powers a lot of the Opus video. Since the visual of a horse in motion has an important role in the story, they took footage at Painted Bar Stables — upstate, in Burdett. “I also shot plenty of videos on my phone of Audrey doing movements,” Hagen writes, “as well as our friend Sarah.”

Hagen storyboarded on paper and tried to stick to that look in his final art. Color and backgrounds went to animator Melanie Kleid, whose work in general follows a kind of automatism — “purely based on my own intuition and nothing else,” as she puts it. That’s how she approached the Opus video, too.

Overall, what’s on screen took a pretty loose and freeform path to get there. Even the concept and story happened that way, as Kang notes:

Like most creative output for me, the narrative came all at once in a manic burst of ideas. When I’m in the process of making something, whether it’s a story or a song or visual art, I can barely keep up with the ideas as they come. It almost feels like I’m transcribing something for someone who talks very quickly... and that quick-talking person is my brain. The original idea for the story was someone riding a motorcycle through a dream world on a journey to save their own soul, but I wanted it to be from the perspective of a child. So motorcycle morphed into rocking horse. And the idea of a dying “soul” morphed into a disembodied adult corpse.

As scattershot as the process was, the end result doesn’t feel scattershot, or come across as just riffing. There’s a sensitive care put into what’s shown, how it’s shown and how it fits with the atmospheric indie rock track it illustrates, which gives the video an impact. It’s a great example of what’s possible with DIY animation.

You’ll find the Opus video embedded below:

Newsbits

We lost the Oscar-nominated animator Eli Noyes (81). Among many other things, he contributed to Sesame Street (the Sand Alphabet segments) and Liquid Television (Art School Girls of Doom).

In China, the promo campaign for The Boy and the Heron is in full swing. The film had its limited premiere in Shanghai this week, with producer Toshio Suzuki present. Ticket pre-sales have reportedly broken 30 million yuan (over $4 million). Its wide release is scheduled for April 3.

On that note, there’s a huge Ghibli exhibition in China that runs until October. Catsuka has photos.

One of the main American stories this week was the release of The Spider Within: A Spider-Verse Story on YouTube. The short debuted last year at Annecy.

Russian distributors are starting to secure foreign animation deals again. Pro:vzglyad has Mars Express, Volga Films has Dragonkeeper and Russian World Vision is apparently planning a major marketing push for its release of The Day the Earth Blew Up: A Looney Tunes Movie.

In Japan, a survey pulled back the curtain on working conditions in the anime industry — putting hard data to the nightmare stories. Cartoon Brew published a good explainer.

A new report for 2023 shows that France’s film industry has finally rebounded from the pandemic. Last year, it delivered “a record 18 animated features.”

In England, the BBC has issued an open call for pitches of children’s animation connected to a few of its major licenses. “It’s open to working with emerging talent and indie studios of any size,” notes Kidscreen. The deadline is April 21.

American animator Michael Ruocco (Snif & Snüf) is prepping a new cartoon short.

Lastly, we wrote about the wool animation of Hermína Týrlová, one of the greatest stop-motion directors.

See you again soon!

Liquid Television’s creator, Japhet Asher, acknowledged Dalí as the source of the show’s title in The Wichita Eagle (June 12, 1991). Dalí’s own quote about his “invention” comes from the magazine Art and Artists (August 1975). Speaking in third person, he said this:

Dalí has invented three-dimensional video. Really, it is nothing. Actually what Dalí has invented is ‘liquid television.’ This means you put the liquid, from a bottle, on your hands, your nose, your clothes. The liquid takes the place of television. … The liquid is the image. The same. It is specially structured to become the image. Like holography. By interference it receives all kind of information, all video information. With liquid it is possible to supply a greater quantity of information. Information is everything. Liquid information is more information.

The Big City is five minutes long, but it was originally planned to be closer to 10. The storyboards Bell showed us offer hints of what this longer version would’ve contained. (He notes that the cuts didn’t really bother him — after all, the whole project was an experiment.)

We drew details about Kambanda’s life from the Los Angeles Times, this bio and especially her essay in the book Becoming American: Personal Essays by First Generation Immigrant Women (2000). Kambanda also appeared in Vogue (August 2005), in an article we reviewed but didn’t quote today.

Asher has discussed the diversity of Liquid Television in the years since its premiere. Like he put it on his site:

I think one thing that maybe has gone unnoticed about LTV is how diverse and inclusive the series was, especially in the political climate of the early 1990s, featuring creators like Cintra Wilson, Peter Chung, Joe Horne and Ed Bell. Our cornerstone characters Aeon Flux and Winter Steele were female at a time when men ruled cartoon hero roles. Art School Girls of Doom featured transgender actors in the lead roles. None of this was deliberate — we had simply generated a context in LTV that demanded a diversity of ideas and styles, a big tent where any voice could, and did, belong.

From a recent interview with Bell at the 2023 Cape Town International Film Festival.

For more on the Good Life Cafe, see the documentary This Is the Life (2008) by Ava DuVernay — and this 45-minute recording of an open mic night in 1993. For more on Sugars, see this interview.

This is from an article that Bell photographed for us: “A Lot to Get You Animated” by Eric Perret.

Hello and greetings!

Big fan of your stack, please accept my sincerest praises.

I wanted to draw your attention on Pakistan's first hand-drawn animation movie 'The Glassworker'. It's slated for release in summer this year after years of labour.

https://youtu.be/bSxHzaDqnQ4?si=q30cmAuVQf1X3DIB

Mano Animation Studios based in Pakistan is behind this pioneering effort, involving collaboration with artists across the world. The founder Usman Riaz was deeply influenced by Studio Ghibli and even had the good fortune to meet Hayao Miyazaki himself.

Wonderful interview with Ed Bell, what a neat career and an epic early project in Big City.