Happy Thursday! In this issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, we’re chatting with a veteran British animator: Tony White.

We connected with Tony a couple of months ago, when he joined Substack. Very quickly, it grew clear that there was an exciting interview here.

After graduating in the ‘60s, Tony stumbled into London’s animation scene out of desperation. From there, he was swept up in history. He joined Halas & Batchelor (Animal Farm), a major studio that was undergoing changes — and troubles. At the time, one manager kept even the pencils under lock and key.

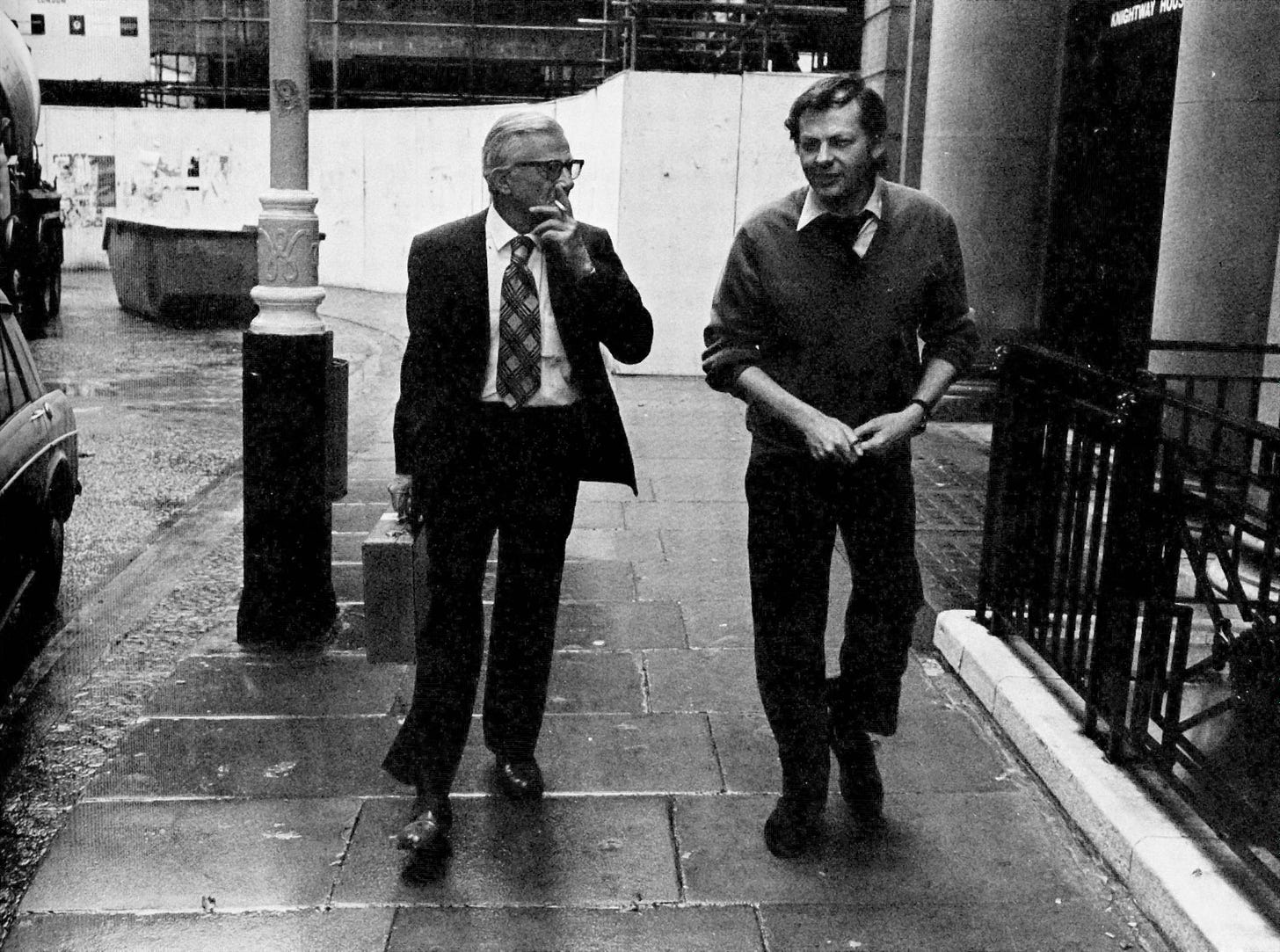

Tony wanted more. So, he moved to the studio of Richard Williams, the artist trying to turn British animation on its head. Williams was a workaholic: his place was wild and rarely easy. Yet Tony thrived there. He describes his first job with Williams, on the Oscar-winning A Christmas Carol (1971), as “pleasurable hell.”

Williams wanted to save the old rules of animation, and he had Hollywood animators like Ken Harris (What’s Opera, Doc?) and Art Babbitt train his team. Tony learned his craft there and carried these skills throughout his long career. He proceeded to do the beautiful Hokusai: An Animated Sketchbook (1978), start his own studio, teach animation (The Animator’s Workbook, 1988), win awards for his ads and much more.

He’d never intended to take this path, but he rolled with the punches. That, Tony tells us, is how he’s always lived. “I never quite get where I want to go,” he says, “but I get to some pretty cool places despite that.”

Today, Tony brings us his unique, on-the-ground perspective of his early years in the industry — a critical time for British animation. Through his memories, you get the feel of the era: the frustrations, the challenges, the triumphs and the mad ambition. In many ways, this was the period that defined Britain’s animation industry to come.

Our teammate John spoke to Tony over the phone. Their interview (edited for length, clarity and flow) begins below.

John (Animation Obsessive): You started your career at Halas & Batchelor. How did you begin working for those folks?

Tony White: It was really by accident. In fact, my whole animation career was by accident.

I went to college to study graphic design — typography. I had a one-year independent study with Ralph Steadman, the famous illustrator. Coming out of college, it was a time when jobs were abundant, and pretty much everyone could get what they wanted in the job industry. I thought I’d just walk into my ideal job, which was going to be more in the area of television, maybe writing and designing TV commercials, and illustrating books.

And none of that happened. I came out and was out of work for many, many months. In fact, I had to move back with my parents. They were very poor, so it was a struggle for them — and it was a struggle for me, especially the guilt side. So, I just started looking around for any job I could find.

There was a trade magazine called Campaign back in those days. You looked at the small ads at the back to find jobs and everything. I ran my finger down the list and saw one that said, “Animation studio looking for a junior background artist. Must have good portfolio of illustration.” I thought, “Well, it’s better than nothing.” I thought I’d apply and then, maybe in a few weeks, make some contacts and get to where I wanted to be.

Out of 30 people, I actually got the job. But it was only the first day I got there that I found out what the job was. I had no idea. I just knew it was in the area of illustration. And, of course, backgrounds are everything that doesn’t move on the screen.

I got into that job and within, I would say, 10 days or two weeks, I realized I totally love this world, and never left it. Basically, that was it.

John: That’s awesome. So, Halas & Batchelor had been around for quite a while by that point.

Tony: Oh, yeah. In fact, they were famous. They’d been around for a long, long while, probably the Second World War onwards. I think John Halas came over from Hungary, either during the war or postwar. It had been going since then. They did many things, but their main claim to fame up to then was, they made the first-ever British animated feature, Animal Farm, based on the George Orwell book.

John: Right. So, what was the atmosphere like at Halas & Batchelor by the time you got there?

Tony: It was a strange place. John Halas was a strange person, in the sense that he was very much a mover and shaker, and he was very in with the network of festivals and production studios and everything across Europe. And he had a love of animation. But he was a very serious person; he was very difficult to deal with at times. There are many stories of him, most of which I can’t even remember anymore.

But it was a pleasure to be there, I would say, because there were some great people. And it was a valuable experience for me because it was a very disciplined studio.

You know, it wasn’t Disney or Warner Bros. or anything like that. But what it did, it followed those disciplines of production. It had the various departments, just like a big-name, Hollywood studio. Although its style was very different to that — it was more experimental in many areas. And they made a lot of government films, which were kind of predictable. But they always did them well and their production system was very disciplined.

I came in as a junior background artist and apprenticed with the existing background artist there. Geoff Chennell, his name was. I was trained up over a few weeks and when I basically knew what to do, they dismissed Geoff Chennell and kept me on. And I felt really guilty and bad about it. Because Geoff was a lovely guy; everyone loved him. I kind of felt guilty even though it was nothing to do with me [laughs].

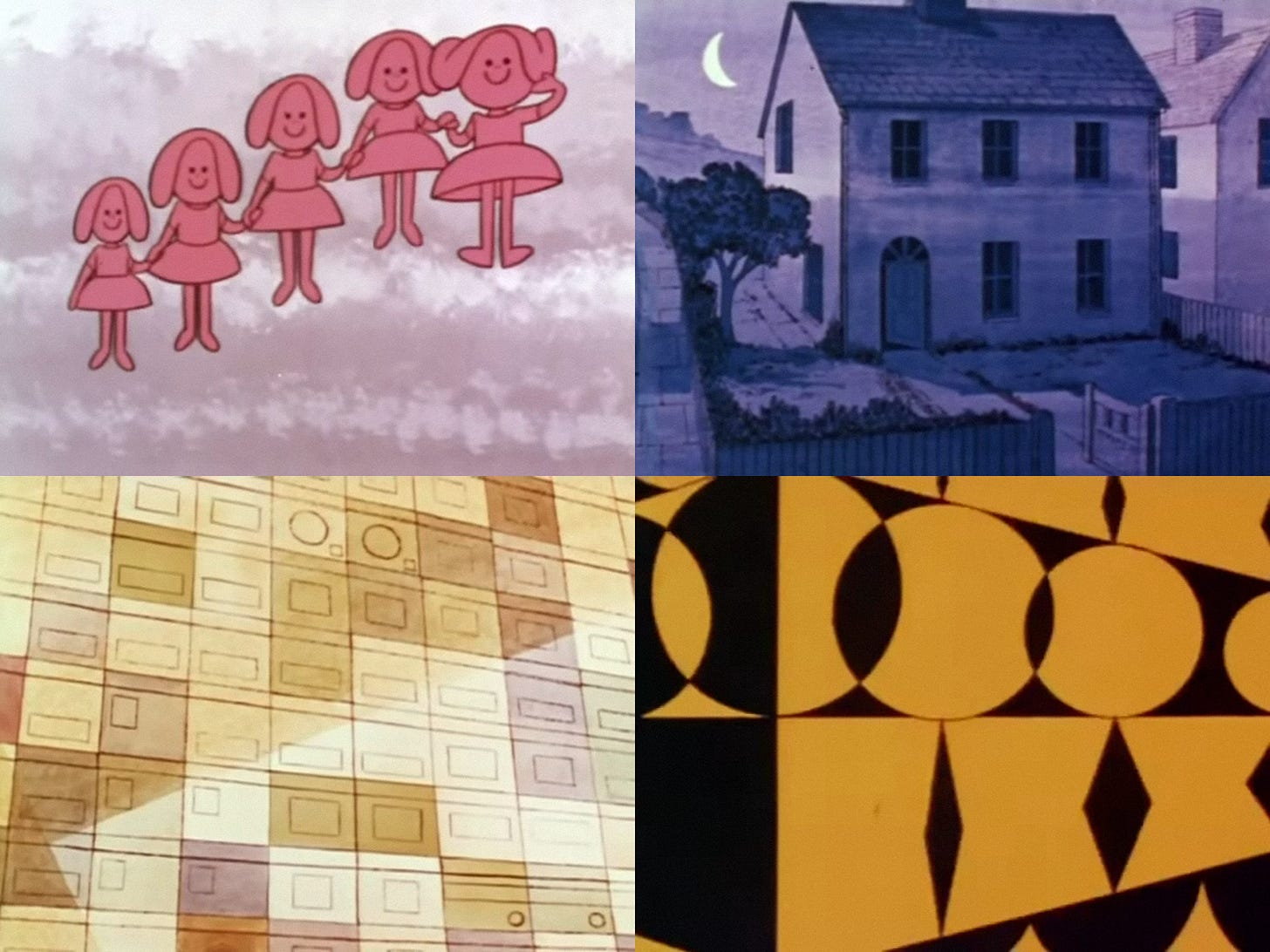

But it was the way it was run. I was cheaper than an experienced artist, I guess — supposition there. The very first project I had which was totally me and not under Geoff’s guidance was The Five. It was kind of interesting to work on that. It was a film for sensible shoes, basically [laughs]. But it was very simple. It wasn’t like a big, challenging art project, and it was pretty easy to do.

I actually enjoyed being there. I think I was there about five years. In that time, it was bought out by Tyne Tees Television, which was a big regional TV network. I think they were in Newcastle or somewhere. A new guy, Jim Nurse, came in and became the managing director, or CEO, or whatever he called himself in those days.

He revitalized it in many ways, brought in some young, very talented people — Geoff Dunbar, for instance. And they completely modernized the look of it.

I fell between the two stools. I loved the innovation of the new thing, but I actually was a great respecter of the tradition and the production disciplines they had. I wanted to be an animator above all, but I was kind of picky. I didn’t find there were any animators I really wanted to apprentice with. So, I stayed in the background-and-design department while I was there.

I got kind of disillusioned. We did two TV specials at the end of my time there. One was called Tomfoolery, which was a bit like an animated Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In kind of show. And then Jackson 5ive, which was just exploiting the Jackson Five — Michael Jackson and the brothers.

It was very much a conveyor-belt thing. My illustration aspirations and things like that were very ambitious, very forward-thinking, and it was all a bit too factory-like for me. I started getting fed up with it for that reason. It seemed like we were only going to be doing TV series, and they weren’t my thing. At that point, I decided, “No, I’ve got to leave. I’m stagnating here. I’ve got to push myself on.”

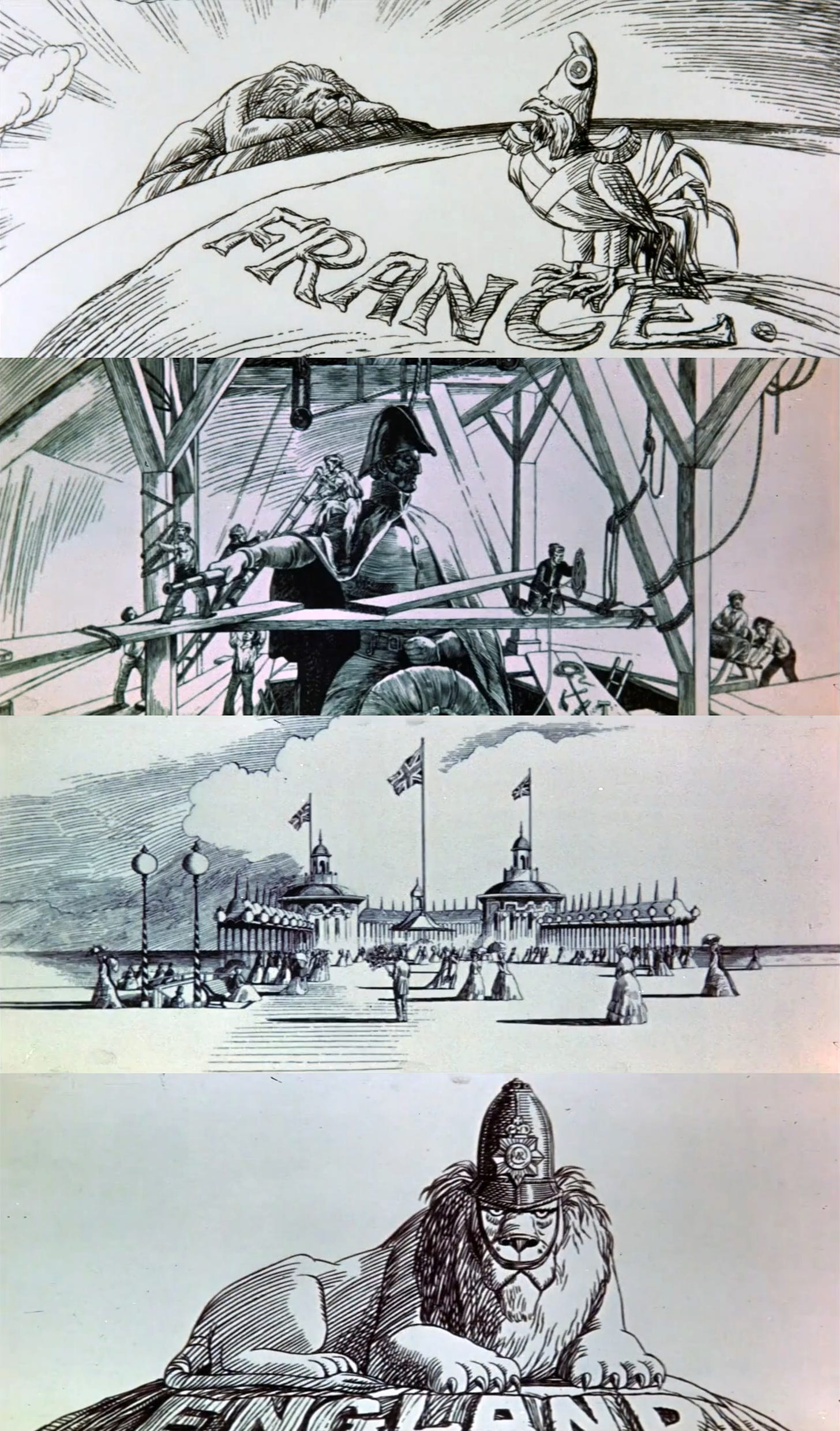

The only light in the darkness of where I was and where the industry was, was Richard Williams, who had been my college hero when I saw some of his work. He was just a hero of mine, above even Disney or anything in Hollywood. Especially the Charge of the Light Brigade title sequence and things like that. They blew my mind and I said, “I want to work with that guy.”

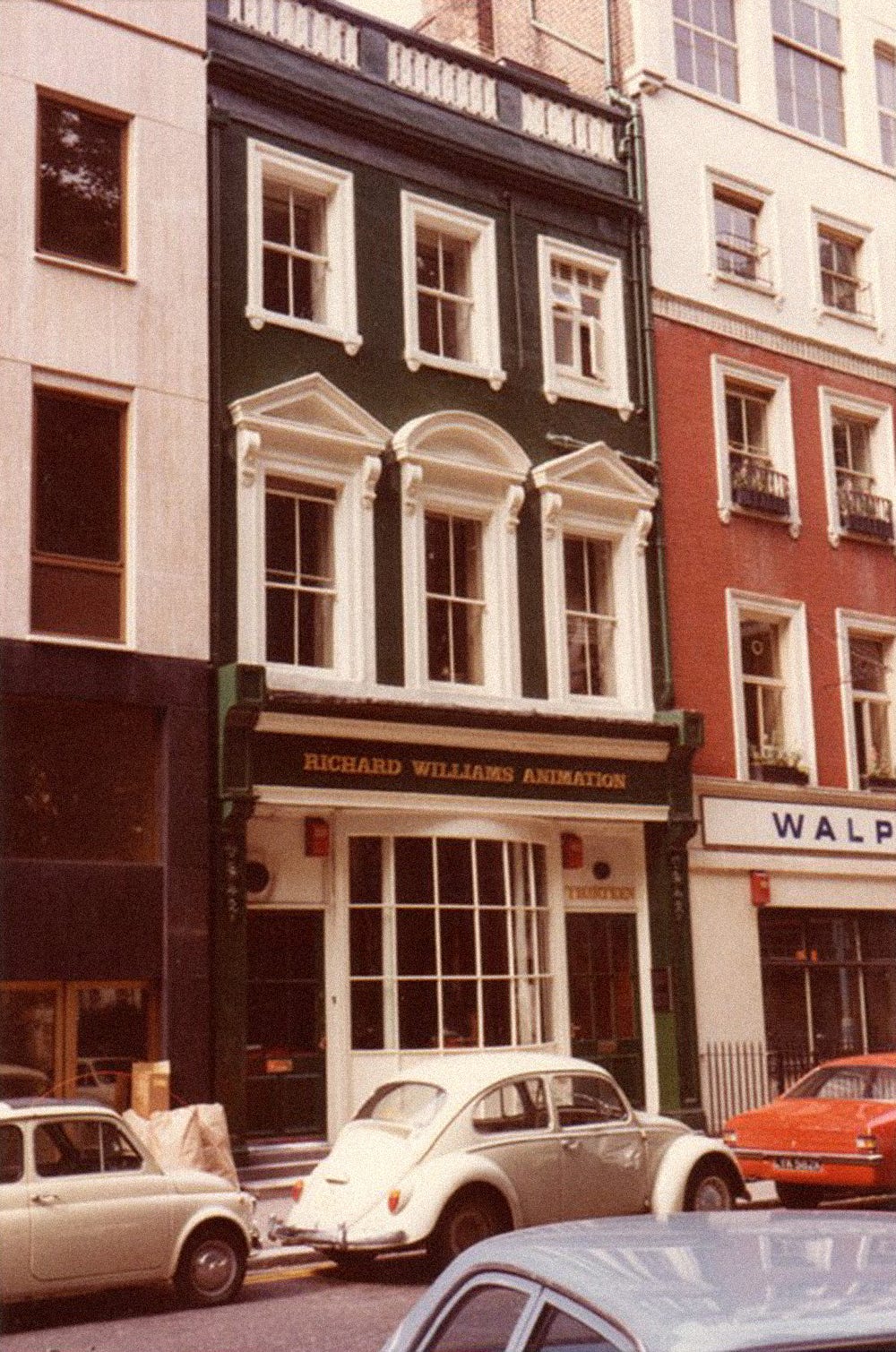

I didn’t even know he was in London at that time. But, when I found out, I sent a letter off and said, “Please, rescue me. I want to work for you.” And he actually gave me an appointment.

John: So, you joined the Richard Williams studio in the early ‘70s? What was the atmosphere like when you got there?

Tony: Oh, it was a world of difference. Let me tell you one more story of Halas & Batchelor which epitomizes why I was so pissed off with it at the end.

It was being run by a studio manager called Bernard Gitter. And he was just a pretty obnoxious guy. As a human being; he probably worked well for the company. He was in charge of equipment, and it was a nightmare to go and ask for something. They didn’t trust you with your own equipment or anything like that.

For instance, and this is literally true: if your pencil wore down, you would have to go to his office and ask for a new pencil. I mean, it was really like kindergarten. And he would grudgingly… he had a cupboard with everything locked up in it. He would sigh and puff and groan that he had to get up and open the door and give you a pencil. And then, this happened several times to me — he’d hand the brand new pencil to you and say, “Make it last longer next time.”

John: [laughs]

Tony: And then he’d lock it up, grumbling and groaning. He was a miserable human [laughs]. And that was true for everyone working at that time; it wasn’t just me. I don’t think he was running it the entire time, but in the latter time I was there, he seemed to be running the whole thing — badly.

There’s a second to that. Hand on heart, I was not responsible for any of this. Before I left, there were a huge number of thefts from the studio. Equipment went, materials went, everything went. I think it was because of the meanness. Like, “They’re so mean, we’re going to take it anyway.” I’m not saying everyone did that, and I definitely didn’t do it. But it did happen. A lot of people were stealing things from that place.

So, you asked me about Richard Williams. There were many, many contrasts — many. But one of them was that Dick Williams was so incredible in the sense that, if you worked there… he didn’t require you to do your own project, but if you were making your own film, he said, “All the equipment’s open to you. Take as much paper and as many pencils as you need, use the cameraman, do anything you’d like. Because I want you guys to get better. If you’re doing your own projects, it’s fine by me.”

So, it was a completely opposite attitude. And, in my five-and-a-half years there, not one thing ever got stolen from that studio. There’s a moral there.

On other levels, it was totally different. Halas & Batchelor were kind of safe; they were very solid, very professional. They did change towards the end when I was there, but, basically, they were more traditional. Whereas Richard Williams was always pushing the barriers, always trying to do new things. And a high demand for artistic ability. High. And a lot of patience and a lot of free overtime.

But it wasn’t a matter of imposing. He wanted people there who wanted to work overtime for no money, because they just loved what they were doing. I was one of those. We worked so hard there. Never thought of asking for overtime.

Once I wrote my letter there, Dick said, “Come in and see me; I want to see your portfolio.” And he said, “I love your work. I want you, but the only problem is, I don’t have a job right now. But you’re top of my list, and soon as a job comes up, we’ll be in contact with you.”

A year went by — I heard nothing. I was so frustrated. I was so fed up with doing TV series work that I said, “Okay, I’m going to try one more time at Richard Williams’. If not, I’m going to go to the Canadian film board because they do really interesting stuff. I want to be part of that if I can’t do it in London.”

So, I dropped a letter — and this is a story of my life, in many ways. When I get to a critical point, and I think all else is lost and there’s nothing, there’s always something comes up at the very last minute. I never get to do what I want to do, but always something happens and saves me when I’ve reached the end of my tether.

This was what happened with Dick Williams. A year later, I sent another letter and said, “Look, remember a year ago, blah-blah-blah?” I got an immediate letter and he’s saying, “Can you join now?” Apparently, my letter arrived on the day somebody resigned. That’s the sort of thing that happens in my life.

Of course, Bernard Gitter, the guy at Halas & Batchelor, insisted I see out my four weeks’ notice. In those days, they paid cash in little pay packets, and you got them 6 o’clock on a Friday night. That’s what they did to me. He saw me through four weeks, until 6 o’clock on the last Friday, and then they gave me my money and that was it. I was gone.

So, I couldn’t join Richard Williams immediately, but he waited. And that was really, really good.

The first day I walked in, I didn’t know what I was doing, who I was supposed to report to or anything. He’d just said, “Come in as soon as you can.” I went in on a Monday morning and said to the secretary, “Oh, I’m Tony White — I’m starting here today. But I have no idea who I’m working with or what I’m doing. Do you know anything?”

She said, “Hang on,” and she went off into the back room. She came back and said, “Oh, yeah, I’ve just spoken to Dick. You’re his assistant — he wants to see you in his office right now.” I walked straight through into his office, sat down and started working.

My jaw was on the floor, because he really was and still is my idol. He’s always been my idol. To not only work in his studio, but work for him as his apprentice, was unbelievable to me. It’s just one of those things that happens to me in my life. I never quite get where I want to go, but I get to some pretty cool places despite that.

John: Yeah, I love that. So, the first thing you worked on was Christmas Carol?

Tony: Yeah. It was financed by a collection of American banks in New York. And they wanted to give the nation a gift for Christmas. Chuck Jones was the executive producer, and they signed Dick through him to make A Christmas Carol.

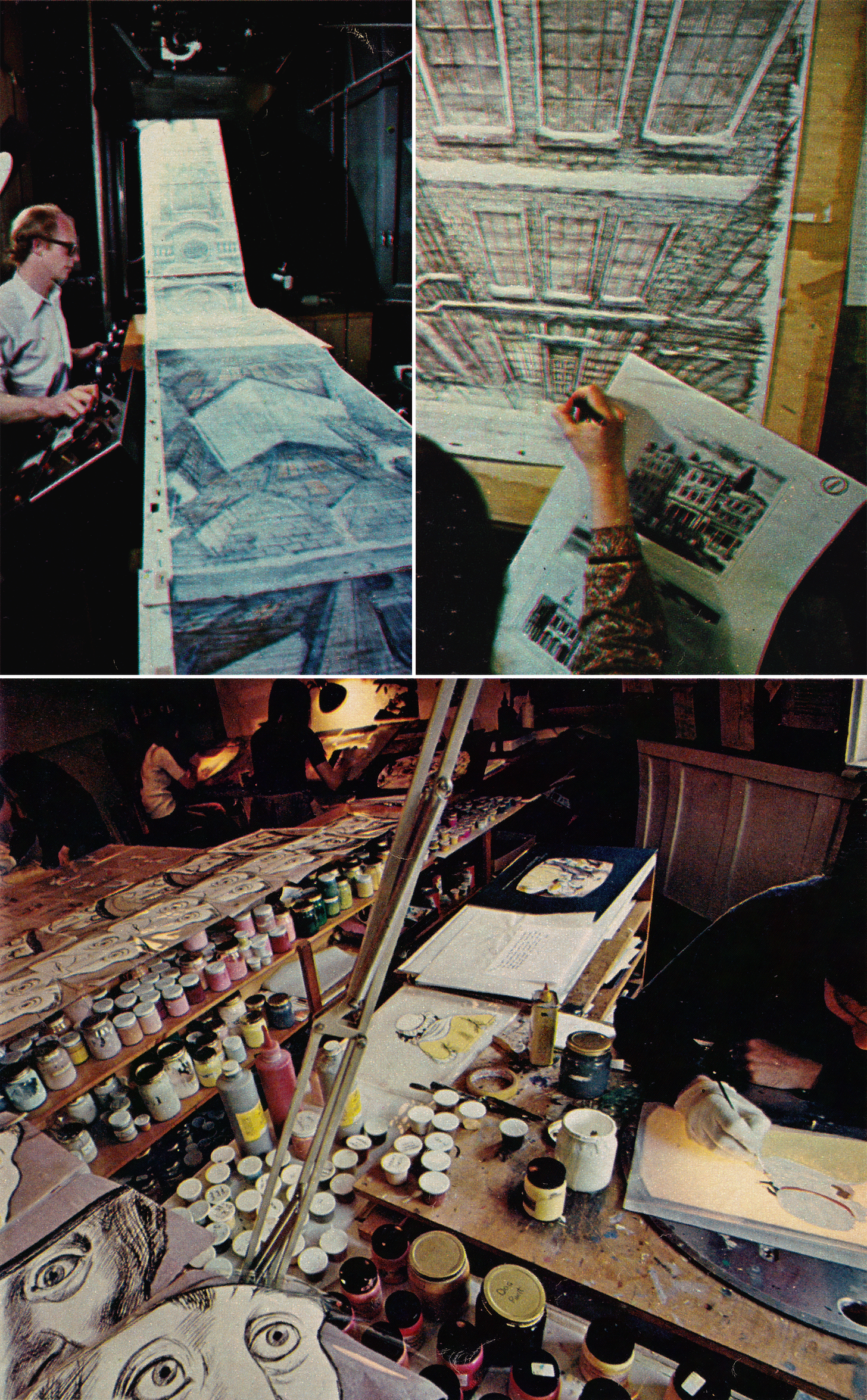

The bottom line was, the contract said he had to deliver a finished, 35 mm color graded master print on something like the third of December. That was it. Remember, no digital technology in those days, no Internet, nothing like that. They had to physically make copies of films, and ship them out to all the TV stations across the country for it to show over the Christmas period.

That’s why that deadline was critical. When I joined, there was some incredible sequences already been done. But Dick was something like six months behind schedule [laughs]. Which is normal, was normal, for him.

He desperately needed the extra help. I was very much thrown in the deep end. I sat with him in his office, him and Dick Purdum, who was the other great there. The office was behind Omar Ali-Shah, the business manager at the time, who was behind the reception.

Everyone else was upstairs, or downstairs in the basement. I only saw them in dailies, or we called them rushes in England. Where you go down in the theater and see the previous day’s work projecting on the screen, and Dick approves or rejects. That was the only time I really met all the other people.

Otherwise, I was ensconced in his office. He rarely went home, and usually when he did it was late at night. Then he’d get back in early in the morning. It was just nonstop. That was kind of infectious.

Anyway, they were something like six months behind schedule with about four months to go. So, it was hell.

John: [laughs]

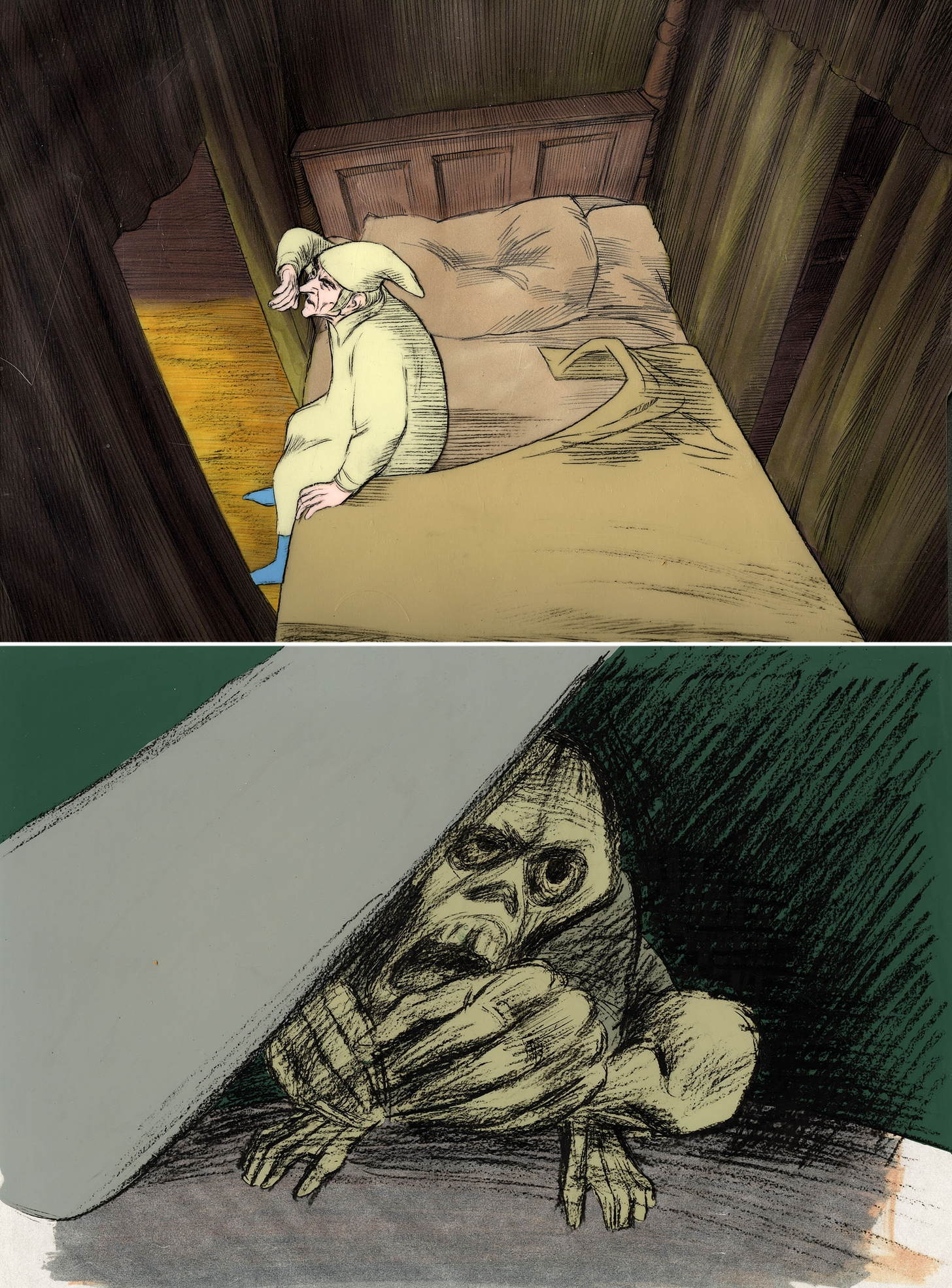

Tony: Especially as Dick would not compromise on the style. It was all that intricate cross-hatching of Edwardian or Victorian England, engravings and illustrations.

After about three weeks, I apologized to him. He said, “What for?” I said, “I’m only doing 10 drawings a day.” And he said, “That’s okay. Because you’re doing very accurate drawings and you’re doing them really well. You’ll get the speed as we pick up, so don’t worry about it. It’s fine.”

And I was worried about it, because I was much more responsible than him with deadlines and schedules. I’ve always been like that — I’ve never missed a deadline. I was really worried that, if we keep this style going, we’re never gonna finish it. I’d multiplied it all out in my head; no way.

But he wouldn’t compromise, and he got a few extra people in. Like, Oscar Grillo came and did a sequence, and a couple of other people came in. Slowly, we clawed it back. Let me tell you that it was hell. But pleasurable hell.

The last three months were seven days a week, probably 12 hours a day, no overtime paid. And the last four days and four nights were without any sleep whatsoever. A core of us, not the whole studio at the end, were working through the night for four days and four nights. And I didn’t even know that was possible. But we proved it was, and we made the deadline by one hour in the morning.

John: That’s amazing.

Tony: The last scene had to go to camera to be shot quickly, to get it out to the labs. They had a daily rush, what they called “daily baths,” where they processed the film. Nowadays, I think it’s overnight, but in those days they had two baths to process film.

It came out at about 7 o’clock at night. That meant it could be cut in and put on a plane overnight, and it made the deadline in New York.

So, it was a nightmare, but it was a wonderful nightmare. Best time in my life. I really loved that production. I was all fresh to it, so the others were a bit more burnt out. But I loved it; I totally loved it. I was so inspired by what they were doing that I wanted to start my own film, which, as you know, was Hokusai.

John: Right.

Tony: When we finished at the beginning of December, four days and four nights without sleep, we all collapsed at I think 7 in the morning, popping champagne and handing over the last artwork to the cameraman.

Dick said, “Okay, have a drink, celebrate. We’re all going home now. I don’t want to see you until January 1. You’ll be paid, but you need the break.” So, everyone was off for a month. But, crazy me, I said, “No, I want to keep doing this. I like this!” I mean, I needed to catch up on sleep and everything, but I studied Hokusai.

I went in every day for most of December and started working on Hokusai on their equipment, because I didn’t have that equipment at home. So, I didn’t really have a break. But, boy, that was a great time. I loved it.

John: So, on Christmas Carol. I forgot to check this — were you still background or were you animating by this point?

Tony: I was basically Dick Williams’s and Ken Harris’s assistant on that film. I got my first film credit on that (maybe I got one at Halas & Batchelor; I never looked). You’ll see, top-left of the mass screen that’s on for a blink, “Tony White, assistant.”

Ken Harris was the ex-Warner Bros. animator who basically animated Scrooge — most of the Scrooge in the film. We were all animating directly on cels. This was the day of acetate cels, and I was cleaning up and in-betweening on cels. Not on paper and then transferring to cel; we were working directly on cel. Ken couldn’t do that, so he would rough out his animation, and I and others would in-between it. Then Dick would do some cleanup key drawings on cels and hand them all over to me.

I had to do the cleanup in-betweens on cels and finish them up for Ken, with all the cross-hatching and everything like that. It was a crazy system, but I loved it.

John: So, you were working with grease pencils on cel, I think?

Tony: Grease pencil, yeah — they were called audiovisual pencils. They were black pencils, very black, and they had grease content. You could draw directly on cel, as long as you wore gloves and you didn’t get hand sweat on the cel, in which case they would slide across that.

So, we had to wear gloves all the time. And some of this was in really hot weather, and no air conditioning or anything. It was challenging to do that. But that’s what we had to do.

John: At Richards Williams’ — you’ve already mentioned Ken Harris, and Art Babbitt was also there, I think, at the same time.

Tony: Yeah, it was a fantastic time. Dick was the great visionary. The problem with him, he wasn’t a good businessman or a timekeeper. But he was a great artist and visionary.

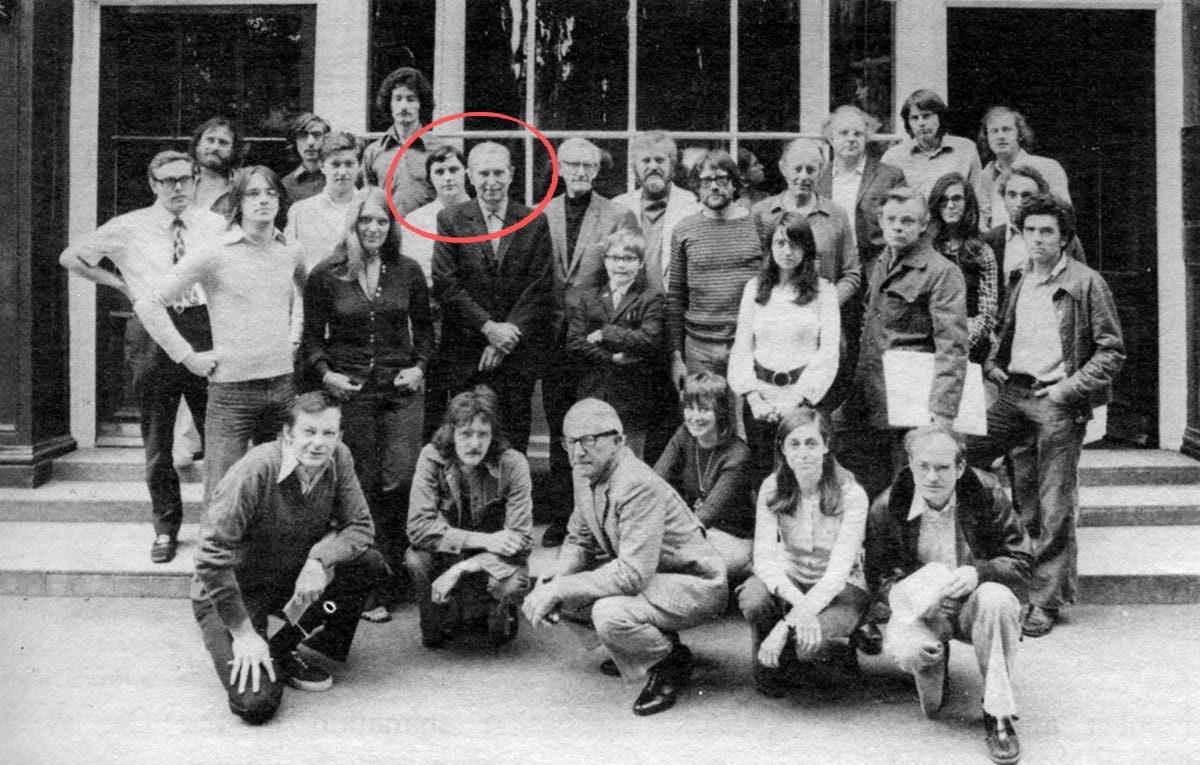

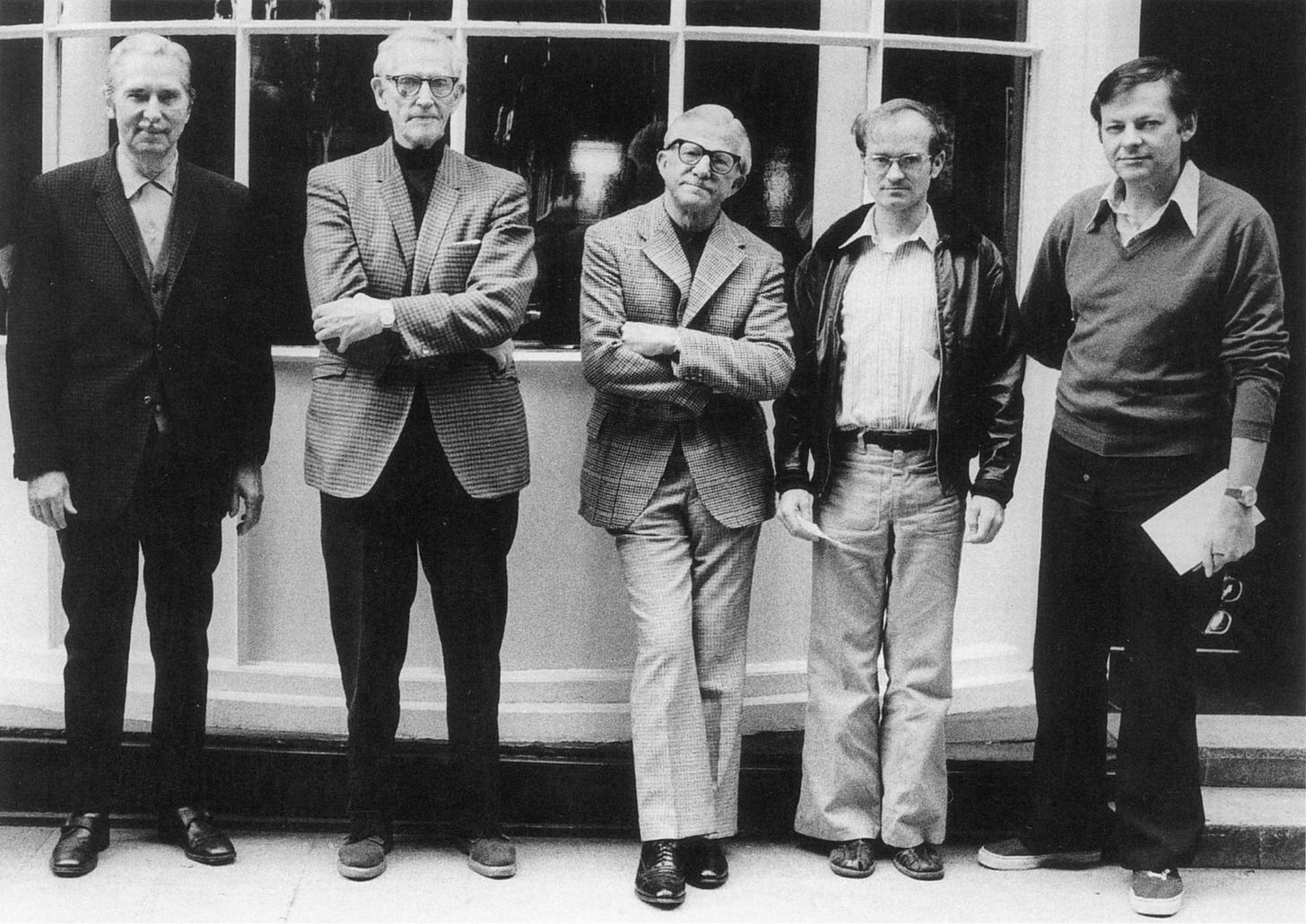

And his vision was, he always told us quite bluntly — very bluntly, as usual — he said, “You British, I consider the British the best storytellers in the world and the best artists in the world. But you’re crap at animation, character animation. I need you to get better, so I’m gonna bring over all these greats from Hollywood and you’re gonna work with them, learn from them, they’re gonna lecture you or do a workshop.”

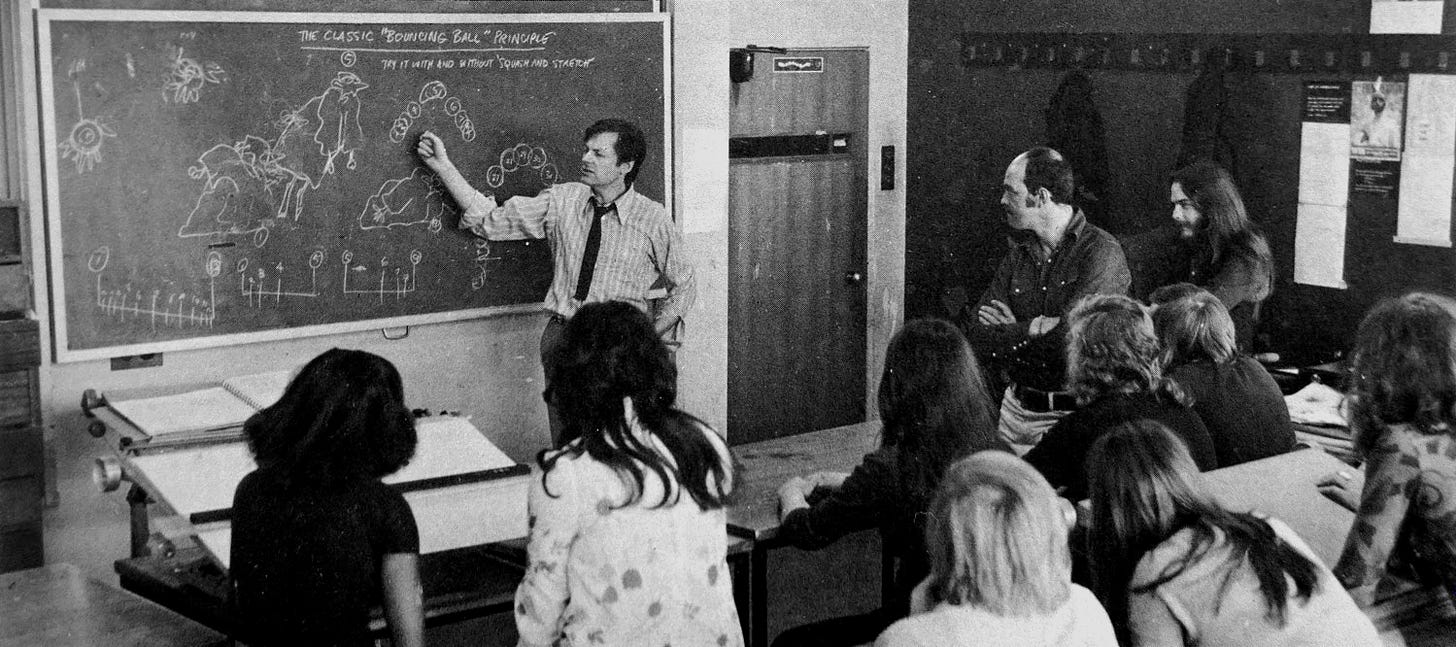

And Art Babbitt was the main one of that. He came over for a month. Dick Williams didn’t exactly close down the studio, but he closed down our lives. Because we still had to do our commercial work, but also had to do arts classes, and do homework, and come back with work and all kinds of things.

So, that was the major study opportunity, which was fantastic. Art Babbitt, the tenth old man of animation. He got written out of Disney history because he led the strike. But he was the tenth old man.

And then Ken Harris was slightly different for me. I was, again, very privileged. Ken had already come over for Christmas Carol before I was there, but he would come over every summer. He was an amazing guy. He was an expert Warner Bros. animator, but he loved tennis. He was a professional tennis umpire. And he always loved coming over for Wimbledon.

So, Dick did a deal with him and said, “Hey, Ken. We’ll look after you, we’ll get you all the tickets for Wimbledon, but you come in and work on stuff for us. We’ll pay for you to do whatever you like in London — just be with us, because I want to train my people up.” And Ken loved that.

My first two summers after A Christmas Carol were sitting as Ken’s assistant, while he was there, doing his in-betweens. Dick’s brief to me was to learn everything about Warner Bros. animation in the Ken style, and then share it with the rest of the studio. That was my job. I didn’t consider it a job; I considered it a privilege. He was a wonderful person, and I learned so much from him in that style of animation. It was just a pleasure working with him.

Dick would fly other people over, but just individuals. I met my second hero of animation, Frank Thomas, the same way.

Another good thing about Dick was, as I said, he’d let you use the equipment if you were between jobs. If you’d finished a commercial and there wasn’t another one starting for a week, he’d let you sit there and work on your own project.

That’s what I was doing, one day; I was working on Hokusai. The door was behind me, and I could hear Dick talking to somebody who was American. I didn’t know who it was. And Dick called out behind me, “Hey, Tony. I want you to meet Frank Thomas.” And I nearly fell through the floor.

Frank Thomas’s first word to me was, “Hokusai! You’re drawing Hokusai! Wow, my favorite artist.” He came over and chatted with me for about 20 minutes, until Dick had to pull him away.

John: That’s amazing.

Tony: There I was in the room with my two animation heroes [laughs]. An amazing time. But Dick did that — that was the whole point. It just raised the bar of his team of British animators. We were like the young old men of animation at the time. It was so exciting to have all these great old guys come over and teach us.

John: What were some of the things that people like Art Babbitt and Ken Harris were teaching you? Do you remember the kinds of lessons and tips and stuff?

Tony: Well, Ken was working on Dick’s film, the Cobbler and the Thief movie. And he was mainly animating the Thief character — he did bits of others. I was really there just sitting with him, and he would animate the Thief.

There would be other people doing his in-betweens as well, but I would be in the same room as him doing his in-betweens. And learning just by being there, like a real, true apprenticeship with him. Whereas Art… you know Dick’s book, The Animator’s Survival Kit?

John: Right.

Tony: That is, I would say, 85% his notes taken from the Art Babbitt lectures. And then Dick picked up things from the other Disney animators when he traveled over there, and he would add to it.

We all had our books of animation. My Animator’s Workbook came from that and a bit of my own experience, having my own studio. But, basically, it all came from those Art Babbitt lectures over the four weeks. He just taught us everything. Everything in those books, pretty much, was the course that Art taught us.

We’d have to animate examples, and he would critique them. Which was really tough because, as I said, we were doing a full commercial load of work at the same time, 9 till 5. We’d have the morning lecture, then we’d do our day’s work. Then we’d go home and do our “Art” work [laughs] — Art homework. And the next morning have it filmed, and have him critique it. So, that was a heavy load.

Then the other ones that visited the studio. A few of them came for A Christmas Carol, of course — we had a couple of ex-Disney animators on there. Others would come and give us a one-day workshop at the studio, but no homework or anything. They’d just lecture and talk to us about different animation techniques, show examples and things like that.

And Art would critique our commercials work as well. He’d look at what we were doing and say, “Hey, you should do this, and you should move that there.” And we kind of felt obliged to redo it, you know?

So, we were doing a double load on the commercials and doing the course at the same time. But it was great. I mean, when else could you get one of the great Disney animators to critique your work on a daily basis? It was amazing.

That’s a wrap for today! Hope you’ve enjoyed. We’d like to offer our huge thanks to Tony White for this fascinating conversation.

And it’s not over yet. Our interview continues from here: we discuss the status of the Williams studio in Britain’s animation community, Tony’s work on Hokusai (1978) and The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976), plus starting his own studio and coming to America. We’re looking forward to sharing it. Keep an eye out for it next month.

See you again soon!

In fact, by the time I was job hunting for work that style was considered very much William’s domain, though the richly rendered very labour intensive illustration style of animation was a trend throughout the early 80’s for several animation studios.

For the newer, smaller studios the trend was toward strong graphic design and a leaner (due to smaller budgets) more experimental approach, that was put to test on the new form of pop promos.

Fascinating! - I have to admit my ambition was to work for Richard Williams but it never happened, much as Tony White says, fate pulls you in other directions.

I made 2 graduation films at St Martins (literally around the corner from William’s studio in Soho Square) both 7 minutes long and one was a collaboration with a former student in my year who directed it and designed all the backgrounds and where I did all the animation in a cross hatched style and used William’s “4 frame cross dissolve” technique to reduce the amount of work for what was a solo effort.

Crazy when I think about it now but it didn’t get me a job there…lol