Poe, Animated

Plus: news and retro ads.

Welcome! It’s a new issue of Animation Obsessive, with a whole new slate of coverage:

1️⃣ The dark vision of The Masque of the Red Death.

2️⃣ Animation news.

3️⃣ [MEMBERS] A retro commercial by British mixed-media animator Osbert Parker.

Not a regular? It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — get them in your inbox every week:

With that, we’re off!

1. ‘The kind of nightmare you quite like’

In 1953, UPA debuted The Tell-Tale Heart — one of the best adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe ever put to film. No less than Guillermo del Toro has labeled it “A+++.” If you animate Poe, you invite comparisons to UPA’s classic. That’s a tough act to follow.

But at least one other grim, creepy, painterly piece of Poe animation holds up against the UPA cartoon.

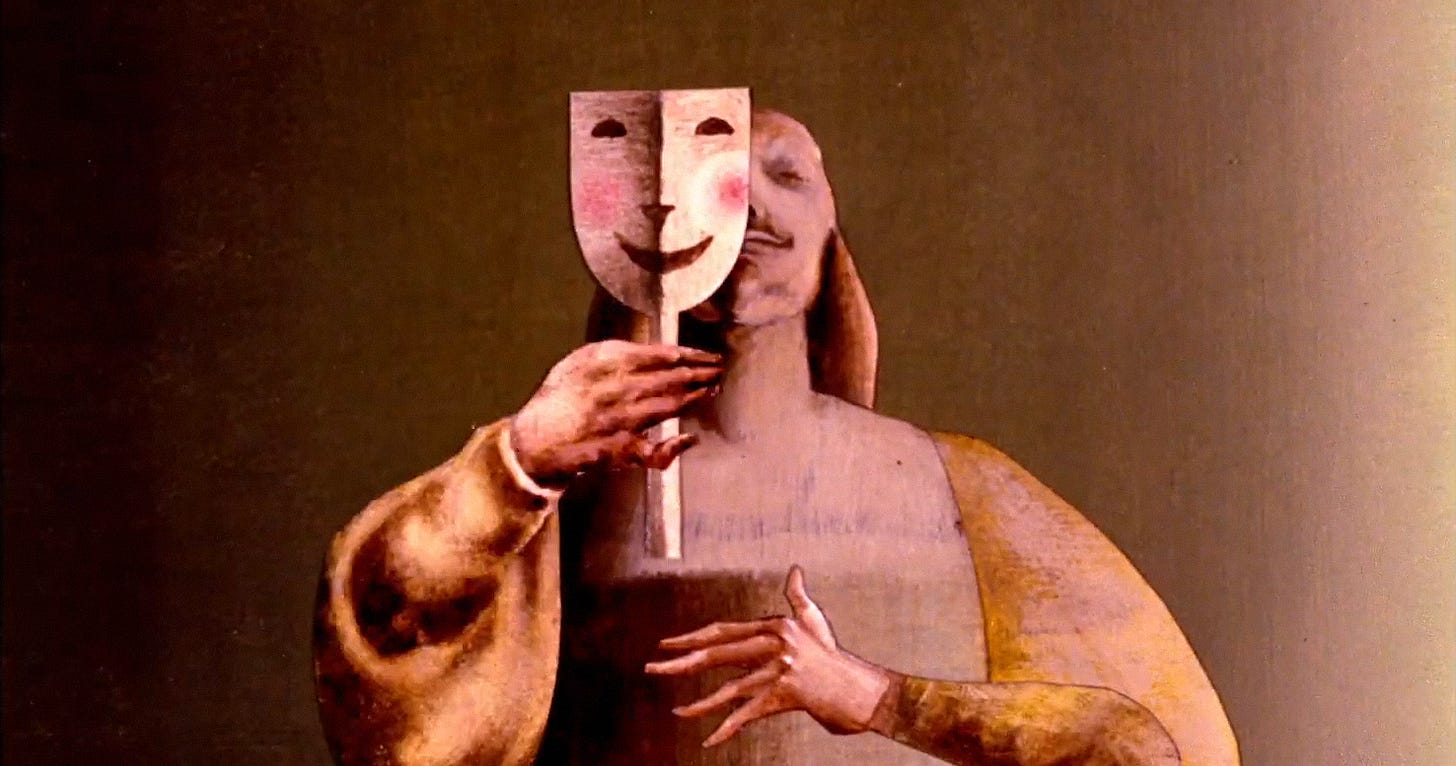

In 1969, halfway across the world from Hollywood, a team of animators in Eastern Europe turned Poe’s story The Masque of the Red Death into an animated short. They operated in the city of Zagreb, in Yugoslavia — a country that no longer exists. But this atmospheric film lives on. In fact, it’s thriving.

This month, the Yugoslav Masque of the Red Death animation was re-released on YouTube in restored form. It looks fantastic, and it begs to be seen again. So, today, we’re revisiting a horror gem — and discovering how and why it turned out so well.

The Masque of the Red Death is about wealth, poverty and the inevitability of death. In the Middle Ages, a plague spreads across the land — yet the nobles remain safe inside their castle walls. When they hold a masquerade ball, a masked stranger appears among them. None of them realize, until it’s too late, who this stranger is.

All of it plays out wordlessly. Masque is a story told through music and art — and it uses a dark, hard-to-pin-down style of animation and visual design. Pavao Štalter, the painter and designer and lead animator and co-director of the film, once summed up the look as “heterogeneous.”1

Štalter, who passed away last October, was a major part of Zagreb Film — the studio behind Masque. At the time, it was a state-funded operation under a communist government. Yet the team faced little repression. Their big concern wasn’t freedom, but money. As Štalter said back then, Zagreb Film was miserably low-tech:

All of our cameras are made from aircraft scrap from landfills. We are madmen who work with abnormal effort. Instead of making a film in three months, it takes us a year. Everything is done by hand. … Here in my little room in the studio, it is 45 degrees Celsius in the summer, and we work ten hours a day! I really don’t know how long we can say, “Tomorrow will be better!”2

Despite the working conditions, this team grew famous for its artistry. The so-called “Zagreb School of Animation” took the festival world by storm during the ‘50s. In 1962, a Zagreb director became the first foreign national to win in the Oscar category for animated films.

This acclaim, and this “school” of animation, kept going through the ‘60s. Masque contributed to it. Štalter called his project “the logical continuation of the development of the Zagreb School.” Its style came from a simple idea — an idea to which the team returned with each project. As Štalter explained, Zagreb animators looked for the “expressive modes that [were] closest to the content.”

The form always bent to suit the film, as it did here.

It took at least two-and-a-half years for Štalter to complete Masque, and he made it largely alone. He first joined the project when one of its masterminds, director Zdenko Gašparović, went abroad to work on foreign cartoons like the original Scooby-Doo.

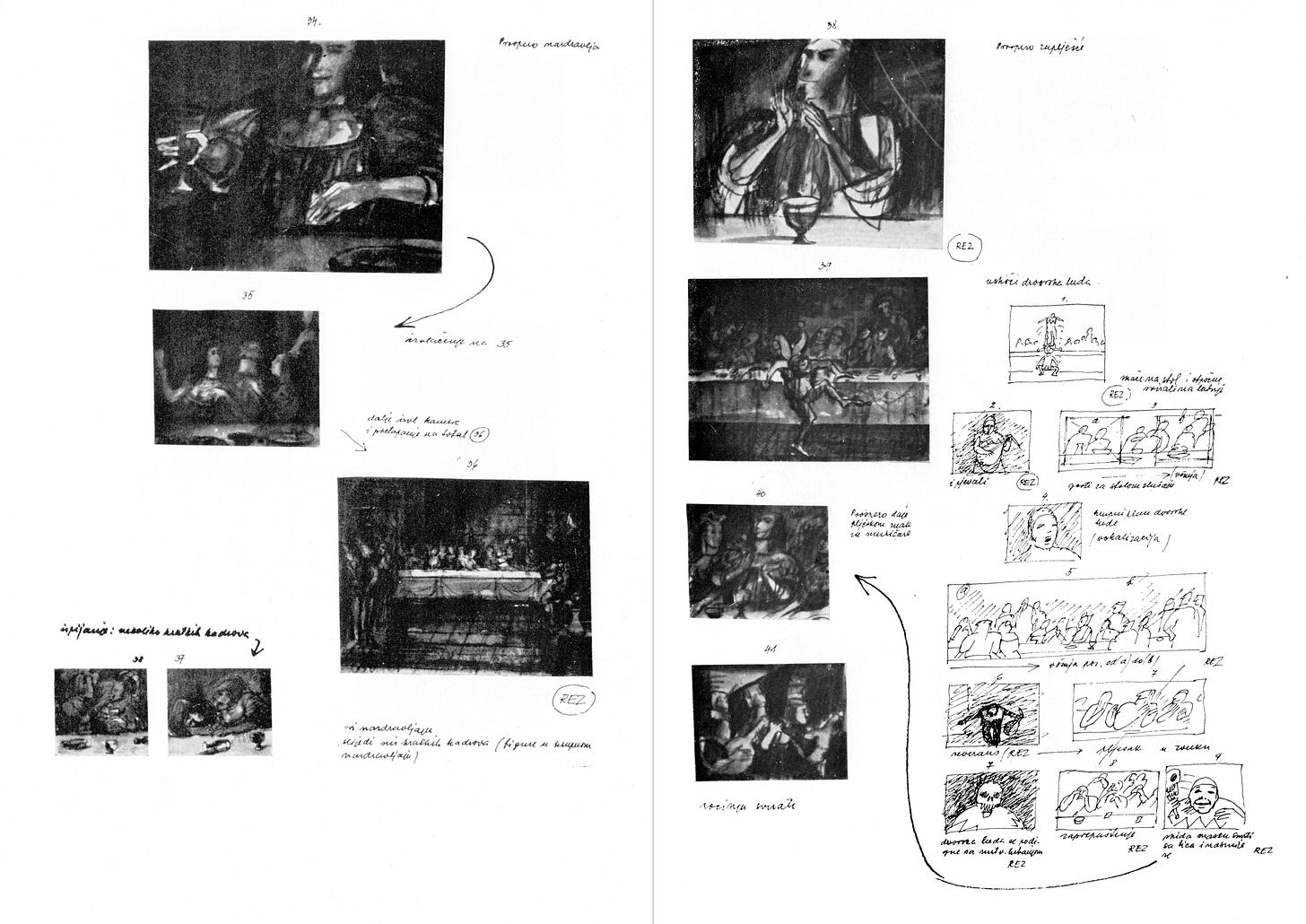

As Štalter discovered, it wasn’t going to be easy to finish the job. Gašparović and his creative partner on the film, co-director Branko Ranitović, had put together a challenging outline that called for “collage” animation. When Štalter started to storyboard the film, he found that it “was in many sequences almost unsolvable with the collage technique,” per the magazine 15 Days.

What followed was a long experiment. Štalter said that Masque was “made in stages, which can be seen in the painting and animation.” His methods changed across the production, creating that “heterogeneous” quality you feel in the film.

His first plan was to do it as a series of stills, flicking by briskly, until he decided that this would be “boring.” Štalter brought in more motion, and leaned into the idea that it needed to be a painted film. He used stop-motion paper cutouts, plus a kind of frame-by-frame animation — at times jotting down an action in pencil, then painting over each drawing with a brush. There are other tricks here, too.

Despite the shifting visual style, Štalter’s filmmaking is tight and consistent. He builds a sense of dread slowly, methodically. Helping him along is the haunting score from composer Branimir Sakač, which goes between classical instrumentation and eerie, electronic effects to set the tone of each scene. Uneasy calm gives way to horror.

The result cuts deep, as you can see below in beautiful quality:

The money to make this amazing thing came in part from an unexpected source. To compensate for Zagreb Film’s low state budget, management had begun to rely on other kinds of funding. In this case, it reached a co-production agreement with a publisher in the United States: McGraw-Hill (through its subsidiary Contemporary Films).

This deal was born in an even more unexpected way. In January 1968, the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited storyboards from Zagreb Film, including Štalter’s pre-production work for Masque. Štalter remembered that his boards impressed the right people in America — which got McGraw-Hill involved with Masque’s distribution. That made a difference.

After its premiere in late 1969, The Masque of the Red Death was acclaimed as one of Zagreb Film’s finest creations by viewers inside and outside the studio — and not just in Yugoslavia. The film screened internationally at events like the London and New York Film Festivals, winning praise and prizes along the way.

Masque was considered for an Oscar. McGraw-Hill took it on the education circuit in the ‘70s, where it played in schools and libraries across America. In his authoritative Animation: A World History, Giannalberto Bendazzi wrote that Masque “can be properly called a masterpiece of animated horror films.”

Maybe the best comment about Štalter’s classic, though, came from the British actor Jean Marsh. In 1975, she told a San Francisco paper that Masque was her favorite animated film, calling it:

... really just like a Bruegel. It’s not animated by jump cutting or anything like that — it’s slow and so frightening, and nightmary, but the kind of nightmare that you quite like, beautiful, and not totally explicit.

2. Animation news worldwide

The radicalization of Russian animation

As you’ve probably heard, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is imploding. But we aren’t military analysts — we cover animation. Only sometimes does the course of the war, and the Kremlin’s growing radicalism in response to it, cross over into our territory. Yet it certainly happened this week.

In one of the most startling animation headlines we’ve seen this year, Putin has set in motion a plan to grant “full state funding” to films for children and teenagers. It’s part of a broad package targeted at film and other multimedia projects, live-action and animated. Putin also ordered regular class trips to theaters, where students will watch films “based on traditional Russian spiritual and moral values.”

Yuliana Slashcheva, the head of Soyuzmultfilm, praised the decision. Even more praise came from Irina Mastusova, who leads the Animated Film Association (AAK). As she said in a statement:

… the government will distribute additional funding for the production of animation aimed at the patriotic and spiritual and moral education of children and young people from next year. … This initiative will be a very timely and relevant measure of state support of the industry, which will allow us to reach a new level of quality. The animation industry is definitely ready to create more meaningful projects.

Rossiyskaya Gazeta, a state-owned outlet that regularly publishes Kremlin propaganda, made the implications of these moves explicit. As an article put it this week:

There is an opinion that this is a step, in fact, towards the revival of the unique Soviet system of children’s cinema, which gave us hundreds of film masterpieces and on which generations of viewers grew up who had a clear idea of the difference between Good and Evil.

These comments about “good and evil” and “spiritual and moral education” are the lingo of Russian nationalism, a movement that grows more extreme in Russia by the day. They represent its soft side.

Less soft are the words of Russian politicians. See Senator Margarita Pavlova’s recent tirade that “Peppa Pig and other evil forces” are part of the West’s hybrid war on Russia, which she made during a discussion about cracking down on “LGBT propaganda” in media.

If these initiatives go according to plan, they represent an effort to co-opt Russia’s animation industry as an outright propaganda tool. Sanctions have left Russian animation in a weakened, struggling state, and the will to resist this pressure may be limited. As Yarko producer Albina Mukhametzyanova said in a new interview, “Today, the animation industry as a whole is going through difficult times … many professionals, who were already hard to find, have left or continue to leave Russia.”

Newsbits

In a big Japanese story, Netflix is dialing back its support for anime — amid reports that “there are not many hits among Netflix-exclusive anime.” Weekly Toyo Keizai claims that the streamer is refocusing on feature-length anime over series.

Until November 18, the obscure Japanese classic Noiseman Sound Insect (1997, Studio 4°C) is available on YouTube in HD.

Ukraine’s preschool series Toto is returning. Its second season, made possible by a Swedish support program, will touch on what screenwriter Iryna Malamuzh calls “our shared traumatic experience.” The team consulted psychologists to keep Toto 2 “safe and therapeutic for children’s psyches and a resource for adults.”

In America, director Jorge R. Gutierrez writes that an artbook for his show El Tigre is in progress and “hopefully will be out by the end of next year.”

In India, Animation Xpress tells the story of Deepa & Anoop, a colorful and well-animated preschool series pitched since 2012. “All major broadcasters whom they met loved their idea” — but “internal shuffling” kept setting the project back.

An absolutely bizarre Chinese He-Man parody, G-Man: A Qixia in Space, is now online with English subtitles. It’s part of Bilibili’s anthology Capsules.

Programmer Adrian Siekierka writes that Dokan, a Spanish magazine, used to publish full copies of anime fansites on CD-ROM back in the ‘90s. These CD-ROMs are now online, and Siekierka is exploring a lost world.

If you’re waiting for One Piece Film: Red to lose steam in Japan, don’t hold your breath. It just hit #1 for its 11th weekend, climbing to $114 million in revenue.

Similarly, months after its premiere, New Gods: Yang Jian is still one of the top films in the Chinese box office. Its domestic take has reached $76.8 million.

The Pakistani feature The Glassworker was picked up by distributor Charades (Belle, Little Nicholas: Happy as Can Be).

Lastly, we wrote about three classics of mid-century Czech puppet animation — by Jiří Trnka, Břetislav Pojar and Hermína Týrlová.

3. Retro ad of the week (Osbert Parker)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.