A Lost Country Broke a 30-Year Streak of Oscar Snubs

The Zagreb School of Animation, plus global animation news.

Hello and welcome to another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter! Thanks for joining us. Here’s what we’re doing today:

One — the Zagreb School of Animation, and how it made Oscar history.

Two — animation news, from all around the globe.

Three — the last word.

We publish every Sunday and Thursday. If you’re new here, you can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free — it’s quick and takes no effort:

With that done, let’s go!

1. How the Yugoslavs won

Yugoslavia does not exist. It was born and died in the 20th century — a culturally diverse country in Southeast Europe, today split into Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro and other nations. Yet it once created some of the world’s most groundbreaking cartoons.

Up until 1962, American directors ruled the Oscar category for animation.1 It was a Yugoslav cartoon that finally ended America’s reign. The director was Dušan Vukotić, the cartoon was Ersatz and the win was so unlikely that Vukotić hadn’t even bothered to show up. Back home in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, his colleagues awarded him a box of Oskar-brand detergent in place of a trophy.

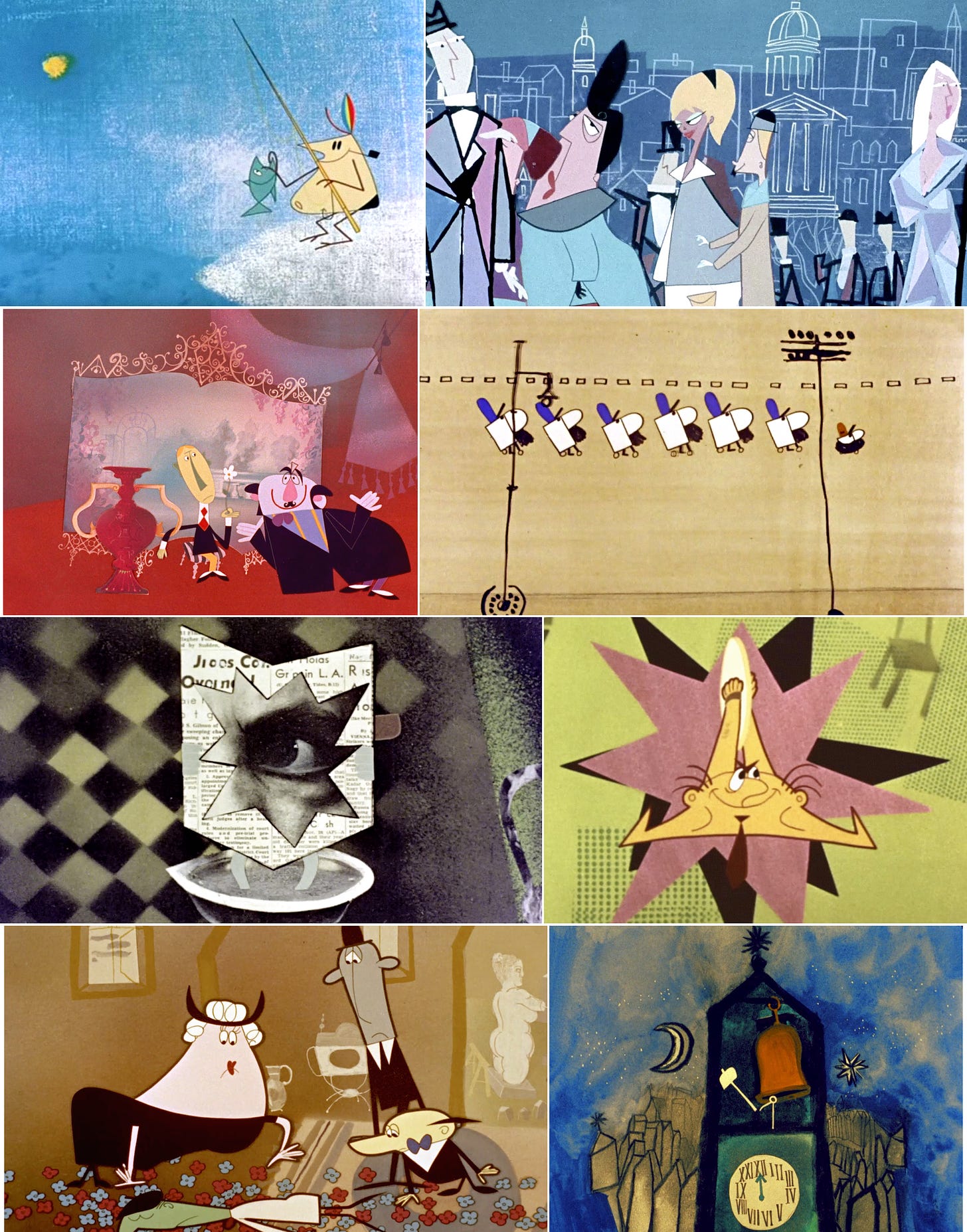

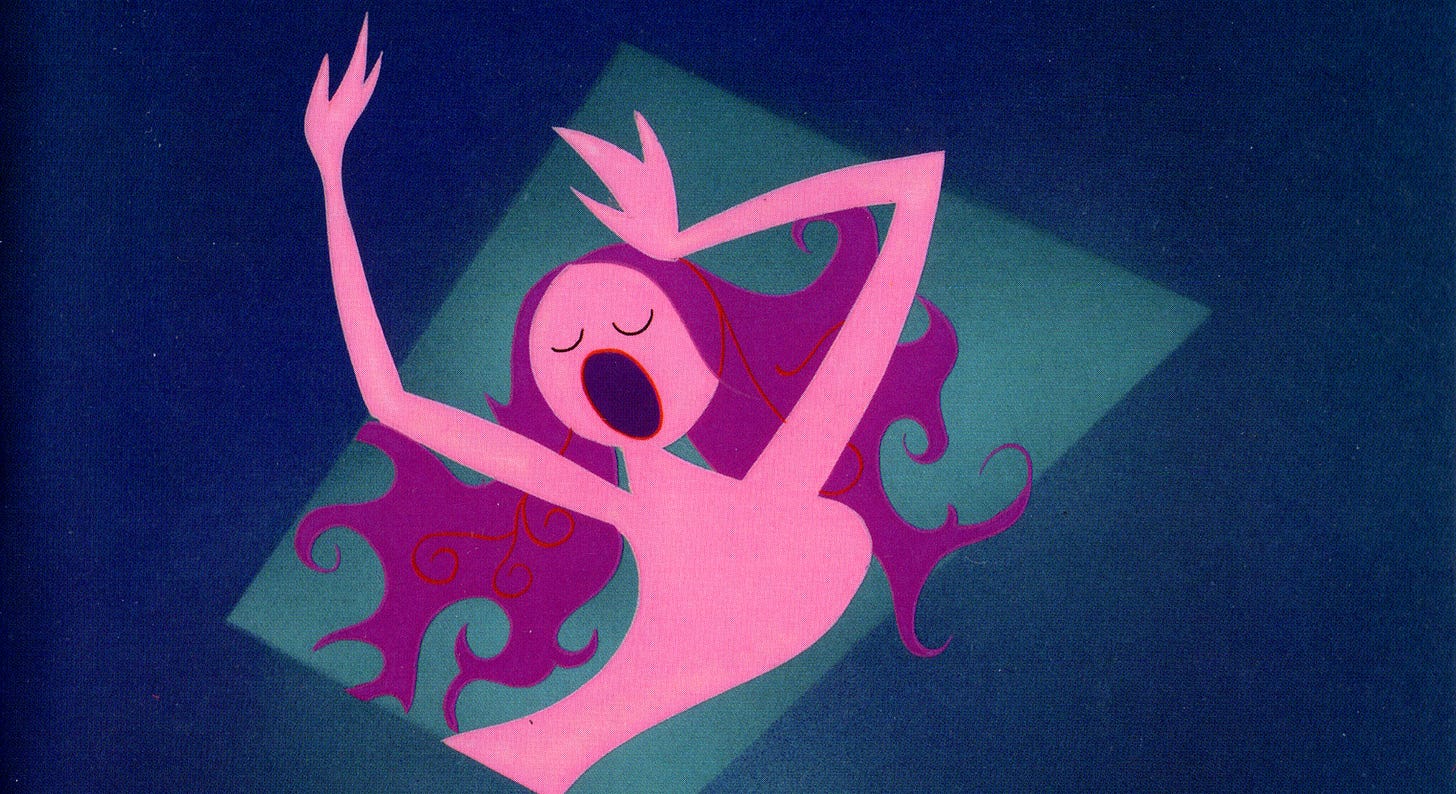

Ersatz didn’t look much like past Oscar winners. This weird, geometric satire was an ambassador for a new movement of animation — specifically, the Zagreb School of Animation.

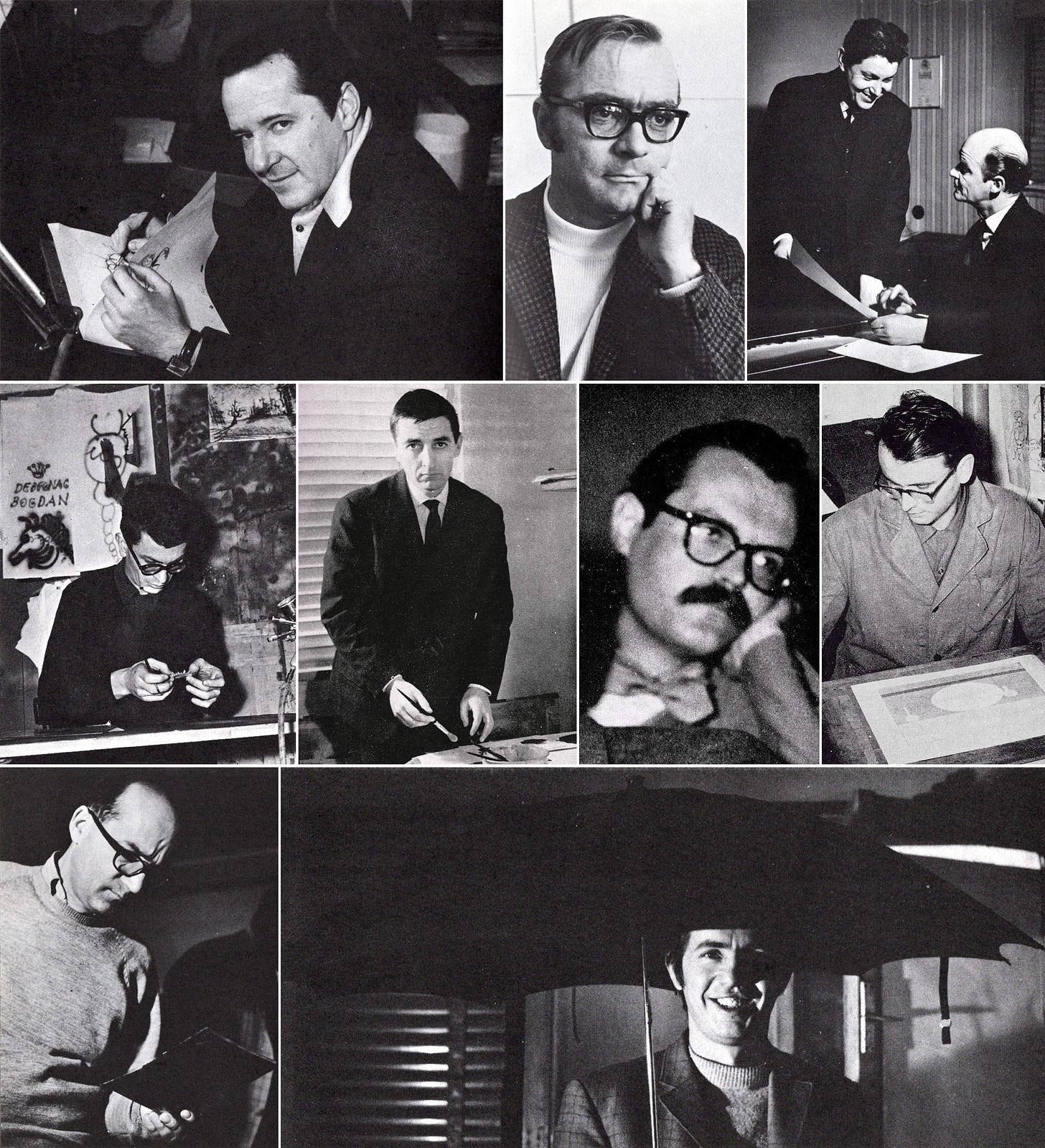

The Zagreb School is a tricky thing to pin down — scholar Ronald Holloway said it best when he called it “a loosely fitting group of artists in open competition with each other.” Many of its key figures were art-school graduates. Even more had a background at Kerempuh, something like Yugoslavia’s answer to MAD Magazine.

It was never just one thing. Zagreb School cartoons are wild and anarchic until they’re sad and serious. They’re cartoony and geometric until they’re loose and painterly. It’s less of a style and more of a “protest,” per a manifesto signed by some of the key members.

This was made possible by the unique conditions inside Yugoslavia. The country was communist — but not part of the USSR, and no friend to Stalinism. A “policy known as workers’ self-management” gave animators state funding without much state oversight, according to scholar Paul Morton. As the book Cartoon Modern put it:

President Josip Broz Tito’s government practiced a liberal brand of Communism, allowing relatively free creative expression. The Zagreb Film artists were thus free to explore all varieties of styles, techniques, and subject matter, in a studio that was largely subsidized by the government. […] Artists could experiment without concern for creating recurring cartoon stars, keeping films to a specific length, or targeting films to a particular kind of audience. Furthermore, a failed film would not result in the termination of an artist’s job.

One of the only creative taboos for a Zagreb animator was to attack Tito himself. “But why would we?” director Borivoj Dovniković later asked. “We loved Tito.”

The Zagreb School planted its roots just before self-management became law. In the late ‘40s, the man behind Kerempuh put his cartoonists to work on an animated film — on his own dime. No one knew what they were doing. “The makeshift camera was rigged up out of an airplane engine,” Holloway wrote.

Somehow, they completed The Big Meeting. Its success opened the door for animation in Yugoslavia.

Joining the scene was Dušan Vukotić, a Kerempuh cartoonist. Other converts from Kerempuh included Aleksandar Marks and Vlado Kristl — the latter a deeply antisocial painter who “suffered from persecution mania.” But there were also architects (Nikola Kostelac), railroad employees (Vladimir Jutriša) and more.

Despite its success, The Big Meeting was unoriginal and a chore to make. The Yugoslavs formed a proper studio, Duga Film, to do better cartoons. Vukotić took a lead role. But state funding wasn’t on firm ground yet — Duga lost its support in the early ‘50s, imploding soon after it started. This killed The Magic Violin, a cartoon Kristl was doing.2 A few years later, he left Yugoslavia in disgust.

The refuge for the remaining animators became Kostelac’s apartment. In his book Z is for Zagreb, Holloway called it “a makeshift workshop” where the “camera and equipment were homemade.”

It was here that they created the little-known Little Red Riding Hood, salvaged from Duga. And they started to do commercials, directed by Vukotić. It was a difficult time.

The key moment came around 1953, when the Yugoslavs got their hands on The Four Poster from UPA. They stole the reel when it arrived for a test screening intended for distributors. “The film was screened by an excited small audience over and over,” Holloway wrote, “and then sent back to the source from which it came — unbought!”

After that, the pieces started falling into place. Vukotić and the others developed what they called “reduced animation,” their own spin on UPA’s style. (This joined one of their biggest existing influences, The Gift, from Czechoslovakia.) It let them make weird and yet highly successful commercials. So successful, in fact, that the city’s main movie studio absorbed Vukotić and his team in 1956. They were part of Zagreb Film now.

The Zagreb School began to blossom. From their first cartoon for Zagreb Film, The Playful Robot, something had clearly changed with Vukotić and his team. This work was completely, unapologetically inventive.

Vatroslav Mimica soon joined the team. A director from the live-action world, his cartoons came to rival Vukotić’s in acclaim — but were nothing like them. Where Vukotić favored gags and pratfalls, Mimica was meditative, surreal. The Zagreb School’s huge creative range was starting to show. “I had completely free hands to do what I wanted,” Mimica later recalled. “It was only a matter of getting the film approved.”

Zagreb Film’s international profile rose quickly. Between 1957 and ‘58, two of the major winners at Venice and the Berlinale were Mimica (with Alone) and Vukotić. They wanted to hit all of the Big Three film festivals — but Yugoslavia’s government wouldn’t approve a trip to Cannes in ‘58. Mimica, a veteran of World War II, acted:

I’d been in Paris the previous year, and I had very good contacts there. They invited me and our films, of the Zagreb Film School, to be projected at a special screening at Cannes. So, I just smuggled the film to Cannes. It was very risky, but I did it. And if the films hadn’t succeeded, I would have had big problems.

Luckily for Mimica, Cannes put the team on the map. It was at this showing that a French critic coined the group’s name — the Zagreb School of Animation. By 1960, Vukotić’s film Cow on the Moon was shortlisted for the Oscar.

There was strife, too. All the awards inspired Vlado Kristl to return to Yugoslavia and join Zagreb Film. He pushed the team’s design sense forward, but battled with them every step of the way. (Holloway called him a “mad genius.”) When someone suggested a change to Kristl’s landmark Don Quixote, he threw an inkwell at them. By the early ‘60s, he’d made a film attacking Tito — and was forced to flee Yugoslavia.

But the Oscar for Ersatz came despite the problems. Vukotić had made better films — yet this one had finally worn down the Academy. Accepting the Oscar in Vukotić’s place, the representative Vlado Terešak said, “I would like to thank the members of Academy for this award.”

“When Duško won the Oscar, it resounded in Zagreb as a sensation,” remembered Lila Andres, Vukotić’s wife.

Although Vukotić took the Oskar detergent home with him, the real Oscar did eventually arrive. Andres woke Vukotić up with it one morning.

As she told the newspaper Jutarnji list, “He shifted, took it still in a haze, looked at it and, as the gold was heavy, it fell out [of his hands] and knocked him on the head.”

Thanks for reading today’s cover story! Before you continue, we’d like to reveal our newly-public student discount for membership. Any student with a .edu address can use it — without the hassle of emailing us for a discount code.

Membership nets you our Thursday issues, where we dig into exciting animation stories too detailed for Sunday. Plus, you’re making the newsletter better — member support helped us buy two books and an article for today’s cover story. Thank you!

2. News around the world

Dirt Girls coming from Victoria Vincent

On Wednesday, Deadline reported that animator Victoria Vincent (also known as “vewn”) is getting a series. Through its studio Bento Box, Fox has picked up Dirt Girls — a comedy in Vincent’s signature visual style. Here’s how Deadline describes the show:

Dirt Girls is set in an alienated suburban neighborhood where two unsupervised kid sisters, Lucy and Pia, find depraved ways to keep themselves entertained while dealing with the confusing, dark aspects of the encroaching adult world.

Vincent is famous for her independent cartoons online, and recently contributed to We the People for Netflix. She’s collaborated several times with animator Jonni Phillips — a major talent we just had the chance to interview.

What happened at MIPCOM

MIPCOM took place in Cannes this week. It’s a trade show that bills itself as “the world’s entertainment content market.” Translated from marketing-speak, it’s where studios link up with distributors, investors and more from the TV business. MIPCOM helps to decide what gets made, and where it’s seen, all over the world.

Quite a few animation stories emerged from MIPCOM. Soyuzmultfilm was a major presence, premiering Coolics (previously Coolix) and securing what Variety called a “raft of deals.” A company in Latvia snapped up the TV rights to 300 of the studio’s retro cartoons. Soyuzmultfilm’s series Meowgic has been licensed in China, and Claymotions is headed to Finland and Israel — among other agreements.

MIPCOM is often about getting existing TV shows and specials on the airwaves in other countries. Shooom’s Odyssey, a special we’ve praised, landed nine deals that will take it everywhere from Thailand to Latin America. And an Italian broadcaster, RAI, was voracious this year — grabbing the French series Esther’s Notebooks, the special Vanille, a Caribbean Tale and more.

It wasn’t just a matter of moving stuff around, though. There was also the MIPJunior Project Pitch — where five finalists competed for attention. The winner was Princess Arabella from the Netherlands, beating Soyuzmultfilm’s Loodleville. Arabella adapts a series of children’s picture books and is set to debut in 2022.

Finally, the International Emmy Kids Awards coincided with MIPJunior this year. Aardman’s Shaun the Sheep won the prize for animation.

Best of the rest

We had a few sad passings this week. One was Ruthie Tompson, an artist at Disney from Snow White through The Rescuers. She was 111. There was also David H. DePatie (91), whose DePatie–Freleng studio created the Pink Panther.

The biggest entertainment story in America, while not strictly about animation, seems to have drawn to a close. Hollywood buckled to IATSE. See what the union won.

Kōji Yamamura’s feature film Dozens of Norths, one of our most anticipated projects from Japan, will have its international premiere at PÖFF in Estonia.

We’ve seen the first images for the next film by director Liu Jian (Have a Nice Day, Piercing I) of China. It’s called Artist 1994, and it follows Chinese art students in the wild days of the ‘90s.

Folimage in France did a fun cartoon about sustainable energy for Hanwha in South Korea. It’s a hit, with over nine million YouTube views so far this month.

Aardman in Britain has released the trailer for its new stop-motion special, Robin Robin, which debuts November 24 on Netflix.

Japan’s Demon Slayer franchise has now earned almost $8 billion. As previously reported, Demon Slayer the Movie was 2020’s highest-grossing film worldwide.

Soyuzmultfilm gets a lot of press in Russia, but the Riki Group is quietly doing numbers at least as big. Its series Tina & Tony (Тима и Тома) is the most popular cartoon on China’s Youku service — Alibaba has teamed with Riki to make more.

The most unfairly panned Japanese film in recent years, Earwig and the Witch, is coming to Netflix on November 18 — everywhere but America and Japan.

Lastly, animation students in Hungary put together a creative music video for TPSRPRT, a krautrock band from Budapest. Check out the result.

3. Last word

Thanks for reading! That’s it for this week. We’ll be back with more next Sunday — and on Thursday, for members.

One final note. Thank you to everyone who enjoyed and shared our issue about Hayao Miyazaki’s union work last Sunday! It was a big success. We noticed that two sites ended up featuring it. Naked Capitalism, a major blog, included our Miyazaki piece in a link round-up. The site Anime Feminist did the same. To both: we really appreciate it.

Hope to see you again soon!

Note that Ersatz wasn’t the first foreign cartoon to win an Oscar. Munro (1960) was secretly animated in Czechoslovakia under an American director. And Norman McLaren’s Neighbours won Best Documentary (Short Subject) in 1953. What makes Ersatz unique is that its director was a foreign national who won in the cartoon category — a first.

Almost no information about The Magic Violin exists. Kristl’s description of it appears in the booklet for the German DVD Der Damm & Film oder Macht, a collection of his work.

Really fun article. Its interesting how the economic systems of different countries can end up influencing the way art is funded and created. It sort of seems that state subsidised animation tends to bring in a lot of animators with unique backgrounds and experiences, similar thing can be seen with the National Film Board of Canada.

Keep up the great work!