Happy Sunday! Thanks for joining us — we hope you’re doing well. Here’s the lineup for the latest edition of Animation Obsessive:

1) Speaking with Chris Prynoski about Downtown (1999).

2) Animation newsbits.

And now, let’s go!

1 – ‘That slice of life’

In August 1999, an unassuming cartoon showed up on MTV. Its title: Downtown. Its initial run: three months. There were just 13 episodes.

This month marks 25 years since Downtown hit the air, but it seems to have more fans today than it did in 1999. It’s a cult series now, prized by many who weren’t alive when it premiered. Last year, it was all over TikTok.

Why? There’s something about this show. It follows young people in New York, in their teens and twenties, during the ‘90s — and it feels like that time. It’s definitely an adult cartoon, and edgy in that late-‘90s way, but it’s deeply real.

Like the great comic series Octopus Pie, Downtown is a snapshot of a New York era, and of the real feelings and experiences people had. It can be funny — and painfully accurate. The lead character, Alex, knows he’s kind of a loser. Jen, his best friend, is the show’s voice of reason, but she’s also kind of a resentful outcast. Alex’s younger sister Chaka thinks she’s cool, but she’s kind of reckless and impossible. All the while, the city is gentrifying around them. The grimy ‘90s are on their way out.

This isn’t a show about stereotypes or cookie-cutter scenarios. These are real people and real stories. And they were based on reality. Chris Prynoski, the creator of Downtown, started with street interviews to keep the show grounded. “I just really wanted it to be accurate,” he tells us.

Today, Prynoski is a name in the industry — he leads Titmouse, one of America’s major animation teams. (It handled Scavengers Reign, among many others.) For the 25th anniversary of Downtown, Prynoski spoke to our teammate John about the process of capturing and preserving ‘90s New York for future generations. Which, as it turns out, was his goal.

Their conversation (edited for length, flow and clarity) begins below.

John (Animation Obsessive): To start off, what led to Downtown? How did the opportunity come to you?

Chris Prynoski: I was working at MTV at the time — I think I was on the Beavis and Butt-Head movie. And, you know, doing other stuff. I’d been on the show, and on Daria and The Head. And I’d animated little promos.

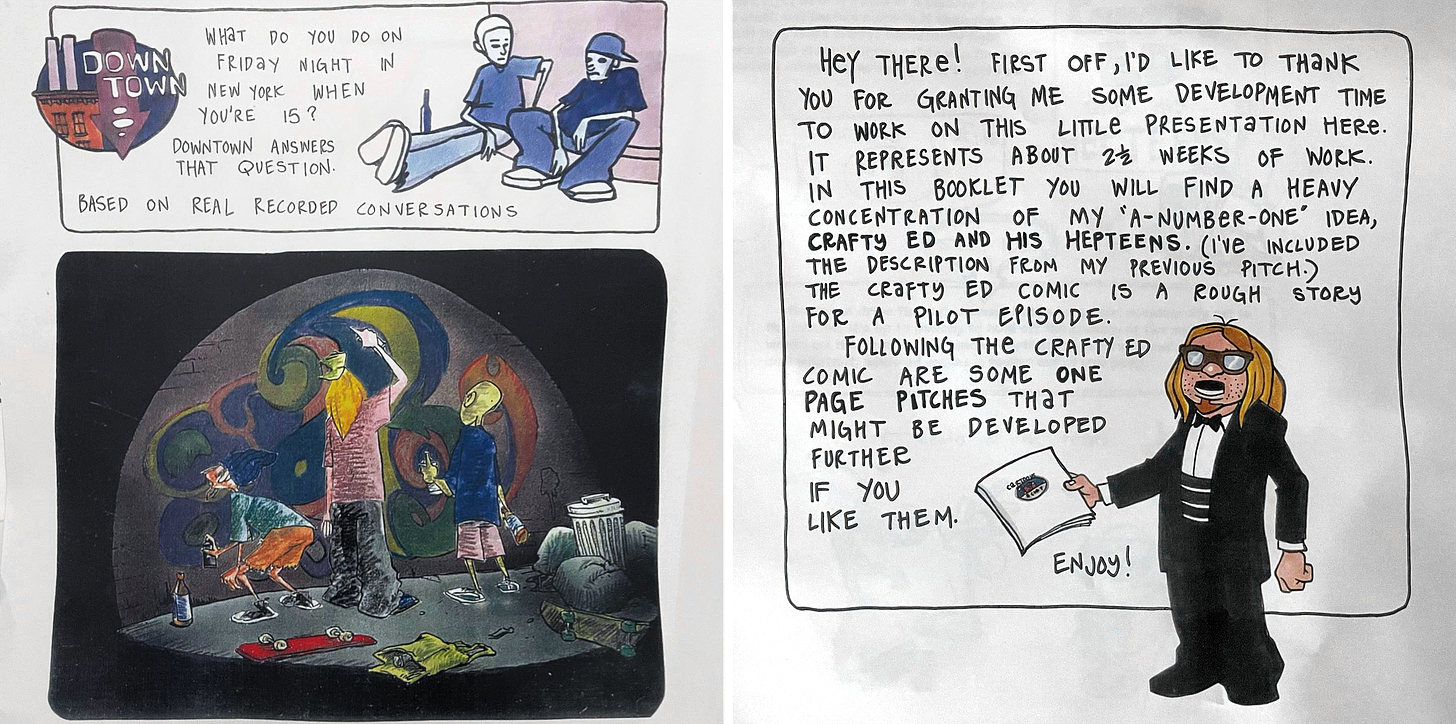

I got the interest of the development guy there, Eric Calderon. He also liked looking at my sketchbook — I filled up a lot of sketchbooks back in the time. They offered me a blind development deal to work on stuff to pitch. I think I had a month to get it together; I worked at night, developing some ideas.

I remember looking at it. I was into a lot of weird, surreal, cartoony stuff, and I thought, “Man, none of this feels like anything MTV has on the air.”

So, I’d done this student film that had natural dialogue. The whole opening was New York teenagers hanging out on the street. The night before I turned in my package, I took a frame from that and drew a little blurb. I forget the exact tagline, but it was like, “Downtown. What happens in New York at night when you’re 15 years old?”

I had really no concept for it. Then I went and pitched and, of course, that’s the one they picked.

I was real inspired at the time… ‘96 was when I pitched, ‘97 was when we started the pilot. Slacker, Linklater’s film about Austin with people wandering around and hanging out, and Kids had come out. I said, “I want it to be like one of these.” And I thought it would be great if it was real man-on-the-street interviews. Take that cinéma vérité all the way.

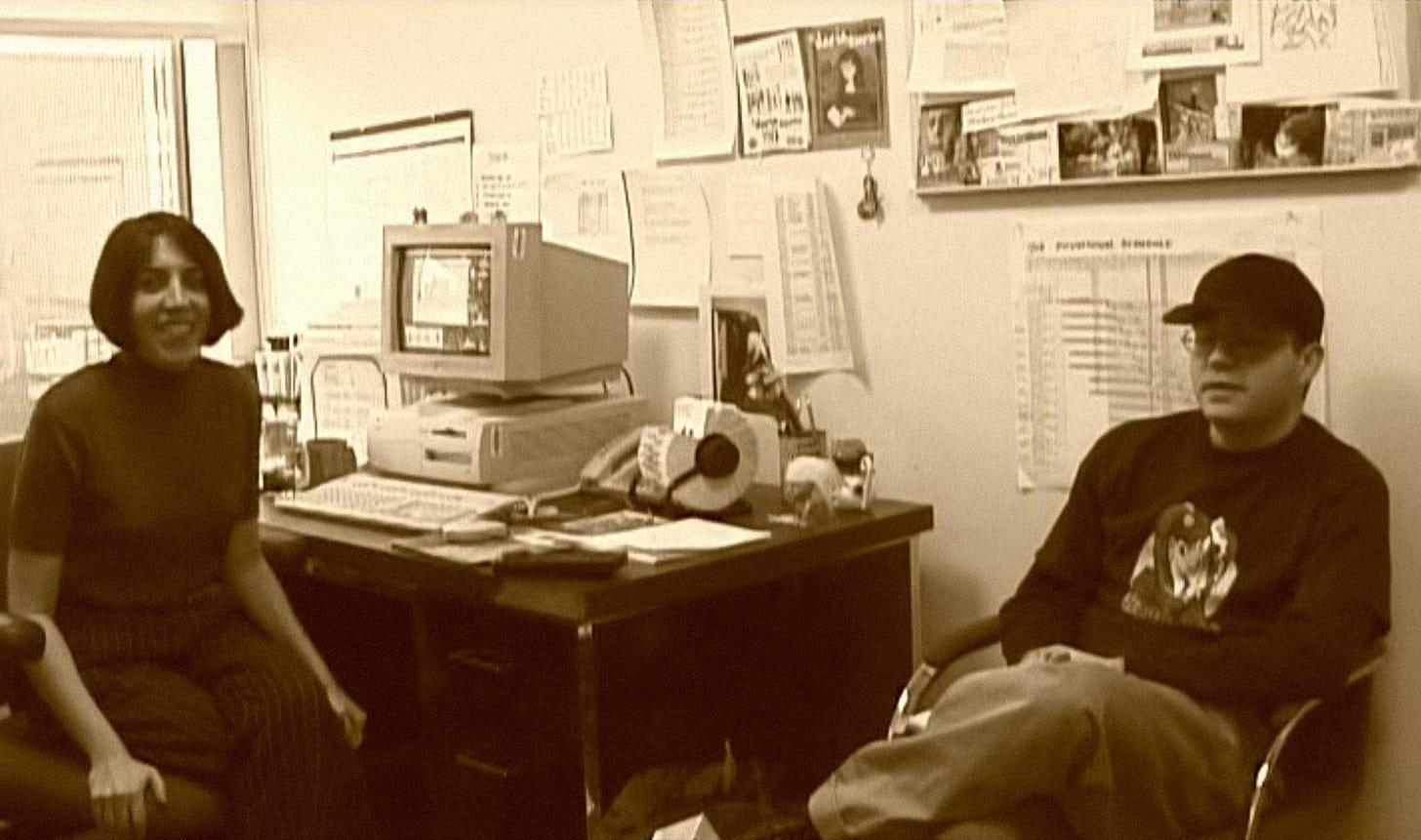

I first did it with just audio, but then I ended up taking a video camera down to the Lower East Side and all around Lower Manhattan, just interviewing people. Seeing who would talk to me. Definitely, being out late at night was helpful, too. And met a bunch of people.

That was the first cut of this thing — cutting together the audio of people I met on the street. And that got the pilot greenlit. I was like, “Check this out.” And they said, “All right, we definitely wanna do this.”

John: So, did you continue to use man-on-the-street interviews during the production?

Chris: Yeah. I wanted to capture this really true essence of New York.

I would watch these Ralph Bakshi films from the ‘70s. They really felt like, “Oh, that was New York 20, 25 years ago.” I thought, “I want to make a show where, 20 years from now, people will watch it and go, ‘This really feels like that slice of time.’ ”

I think, if I did anything — that’s definitely what people tell me. It’s that moment of time in New York. That slice of life.

In the pilot, I honed in and found a few regular people to talk to. My idea was not to have scripts and not to cast people. Just to use the actual, on-the-street audio. Once the pilot got greenlit, [MTV] said, “You have to write a loose script — it can be based on these stories you gathered. And you can cast people you met on the street, but we’ve got to bring them into the booth and record ‘em.” So, we did that.

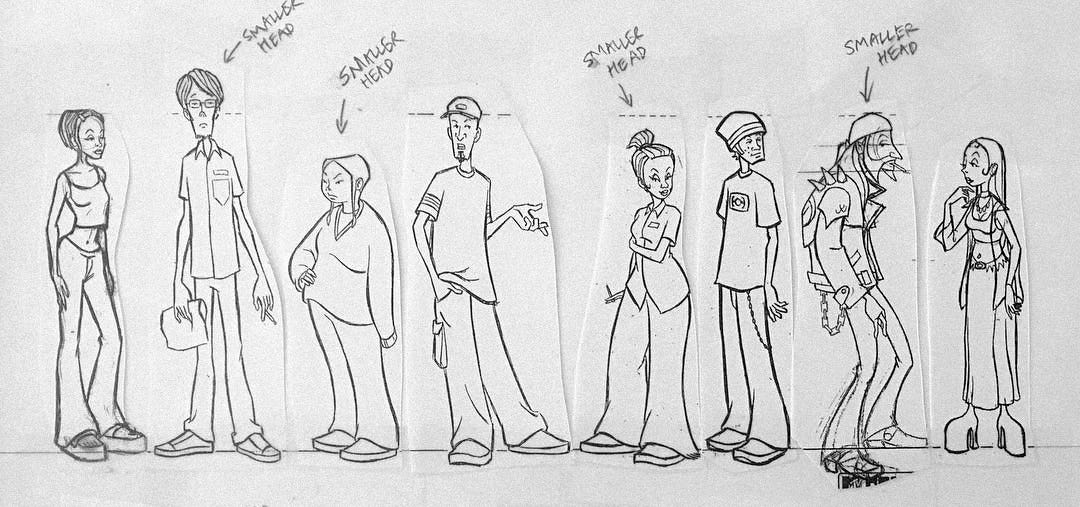

The pilot was primarily about the teenager life, their whole scene. When the show was greenlit, I was pushing not to have a regular cast of characters. To have a very large cast you’d dip in and out of. There was no main character or even main set of characters. That wasn’t received well by the higher-ups, so we cut that down. We also expanded it up to be more people I felt we could write to.

The three, every-day writers were me and George Krstic, the story editor, and Anne Bernstein, who I worked with on Daria. We had the 20-somethings [in there] — I was in my mid-20s at the time. That’s where Alex, the older brother, came about, and some of his friends.

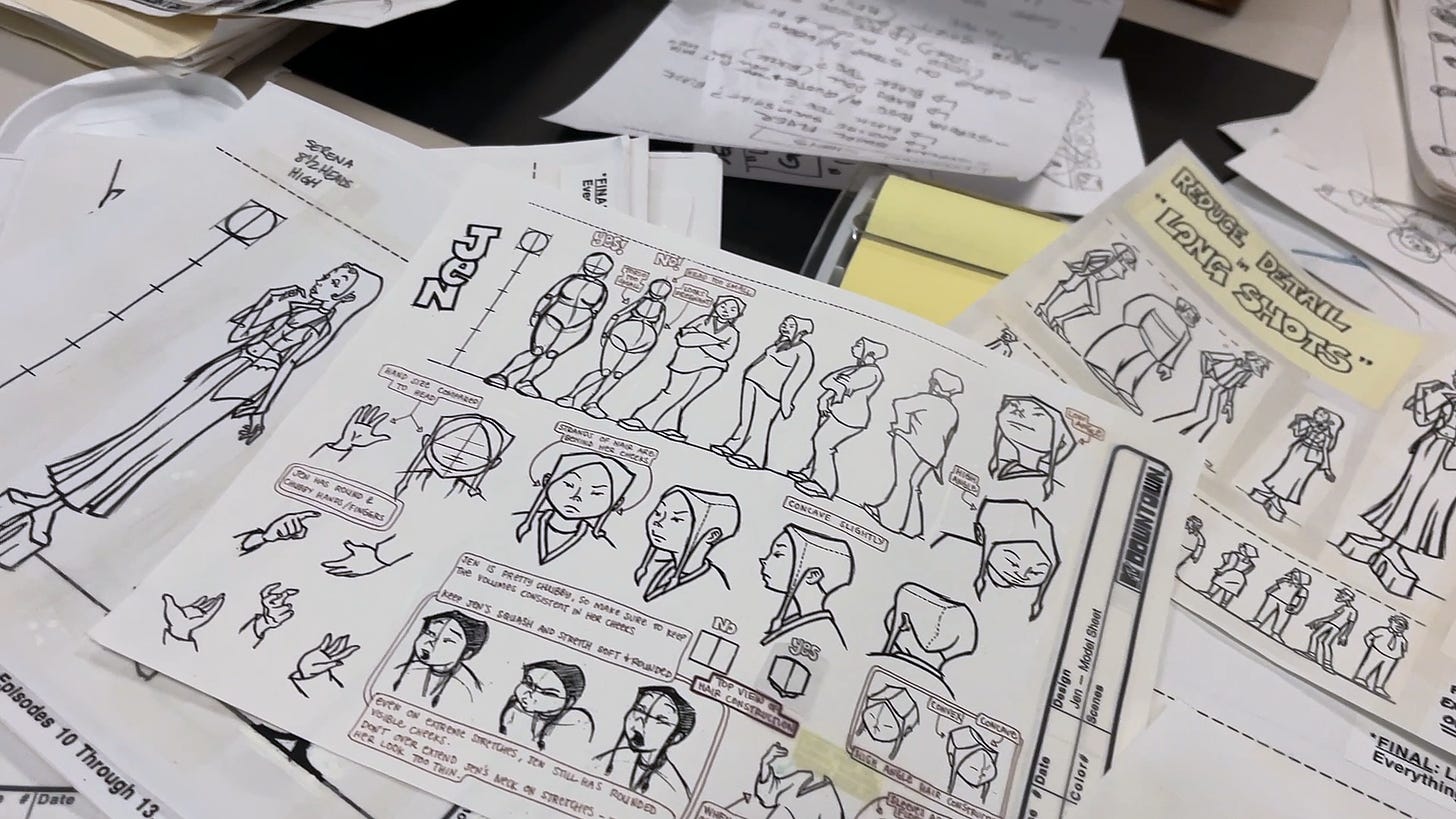

I’m so glad we did that. They were good foils for each other, the younger sister and the older brother, Chaka and Alex, having very different points of view. We went out on the street to interview people and come up with characters for that older set, too. The person that Jen, Alex’s friend with the long sweatshirt sleeves, was based on — we interviewed somebody who had that kind of look, and we borrowed that.

We were inspired by a lot of things. The people we met weren’t always the people who did the voices, but the voice cast almost entirely was made up of non-actors. Even the people we got who were actors, in air quotes, were pretty young and pretty green. And everybody was the age of the character they were playing. The 16-year-olds were 16; a 22-year-old was 22, or thereabouts.

John: What were you looking to communicate to the audience about this time and place, and these people?

Chris: You know, I just really wanted it to be accurate. I loved living in New York, and I loved that kind of scene. I loved hanging around in the Lower East Side. I wanted it to feel like that.

I didn’t initially intend for this show to be a comedy when I pitched it. I said, “I really want this to be a slice of life, kind of a drama.” Not a drama, where there’s a lot of conflict — just a much less joke-heavy show. And I got pushed back on that, too. They’re like, “It’s gotta lean comedy.”

I don’t think that was ultimately bad for the show, either. It probably gave it longer legs. I really wanted to make an artsy-fartsy thing [laughs].

John: [laughs]

Chris: It would’ve been a personal art film if they’d let me do what I really wanted to do. So, in some ways, it’s good when you get pushback from network and exec. Like, “Hey, we gotta put something on air that we feel our audience is gonna want to watch.”

But, really, it was authenticity. Accuracy. Mood. That’s what I was going for. I don’t think I had the idea of an overarching theme. To me, it was more about that era. That was the era of the slacker — when that term was being thrown around a lot.

I felt like that time, and the time before I was working at MTV, it was just a lot of hanging out with your friends. I wanted to capture that time — that I don’t have anymore. As you get older, maybe, most people don’t have it anymore. Where you didn’t have an agenda, you didn’t have a plan. You were just hanging out, you know [laughs].

John: You mentioned the late Anne Bernstein — I was going to ask about her contributions to the show.

Chris: Oh, she was great. She was an incredible contributor.

She came on during the pilot to help craft that script with me. I’m very comfortable doing board-driven stuff, but it was a weird thing — there were these interviews, and you wanted to take the language. It was this back and forth of script, board and audio track, building this thing together.

She was really good at understanding the tone and putting together the structure for that pilot, so she came on to be the head writer of the series. My college friend George Krstic ended up being the story editor. They were in lockstep with me, just beating out stories in the writers’ room. We worked with a bunch of freelance writers, too.

John: Once you had the man-on-the-street interviews, how did you and the writers drill down on what you wanted from that naturalistic raw material?

Chris: It was a real organic process. We watched all the tapes over and over again, and we knew who we were going to end up utilizing for the series, so we tried to write to their voices. There were multiple refinement processes.

You’re breaking this thing in the room, and then it goes to the episodic writer. Then they come back, I do my tweaks and we do a table read with the actors. And a lot of times they’d have opinions on stuff. Like, “I don’t know. This doesn’t sound right.” We’re like, “Hey, how would you say it?”

We would have a pass of getting the dialogue more authentic. Then, in the booth… part of the process of recording, and this is something I still use to this day, is you do a run. A lot of cartoons are recorded line by line. You say, “Hey, give me three passes of this line,” and then you go on to the next line. But I like doing runs. Andrea Romano, I loved working with her — she would always do these great runs.1

We’d do a two- or three- or four-page run with the actors all in the booth. You get ‘em to do a run of the written page until you feel you’ve got that enough. Then you say, “Keep the pages in front of you, so you have the structure of the scene, but now say whatever you want instead of the lines written there.” You’d do that a few times.

Once they’ve done that, and you have six takes or something, then you have them throw the script out. Like, “Don’t look at it, and just do the scene from memory. Half-improv it with the other people in the room.”

We would generally use material from all three of those passes. It was never one exclusively — it always ended up being a combo. And those loose ones made it in there a lot in Downtown.

We recorded it at Sync Sound. Ben McCrea was the voice director — he worked with me. Danny Caccavo was our engineer. He was a great engineer to work with, too, because he got it. Most shows, they say, “Take out spaces, take out breaths, take out hiccups, take out stutters.” I’m like, “We actually want that stuff in here.”

John: Aside from yourself and the people in the writers’ room, who were some of the key contributors to Downtown?

Chris: Oh, man. There’s so many people.

One person I want to give a lotta credit to, on the animation side — Dave Vandervoort. I worked with him on Downtown and other stuff in New York, but also at Titmouse in LA. He ended up moving up to Portland, getting into the stop-motion and feature scene, with Laika and Netflix and other places. He’s one of the most naturally talented animators I’ve ever worked with.

What happened was, we’d hired a few people. When we had to rewrite our scripts — like, “No, you’ve got to have a regular cast of characters” — it pushed our schedule back six months. In the days before cell phones, Dave was already on his way out to New York, and he didn’t get the word that the schedule was delayed.

The producer said, “Well, he’s here now. Why don’t you use him?”

I was animating walk cycles and little moments of the characters as examples. At first, I had him assist me. I said, “Can you in-between this stuff?” Then I’m like, “Man, this is good. How about this — I’ll just give you the very broad key poses.” Then it looked even better. I went, “I’ll just do one drawing for you.” Then, “I’m just gonna act it out for you, and you animate it.” [laughs] And then it looked perfect.

I was, I think, 25. He was 19. He was so young to have that much skill. In my opinion, the best 2D character animator at MTV Animation in the whole building at that time.

But there were a lot of talented artists. Another person was Antonio Canobbio, who’s my chief creative officer at Titmouse. I’ve been working with him for 25 years. I found his drawings in the fax machine.

He had cold-faxed drawings from Paris — he had gone to Annecy and gotten the book with every studio’s numbers, and was just trying to get a job in New York. He loved comedy. A lot of the French guys were going over to work on Prince of Egypt. I think he could have done that, but he wanted to work on something funny, so he was really trying to get into MTV.

I just happened to find his drawings, and did something I would never do now. MTV was such a weird and fun company, but it didn’t vet like studios should do, or do now. It’s like, “Hey, here’s five drawings I found from a guy. Hire him!” And they did. No interview, no references [laughs]. No seeing if they were even his drawings. Luckily, it worked out. He was great on that show, and that’s why I continue to work with him to this day.

John: What was the animation scene in New York like at that time?

Chris: It was pretty small. I mean, New York is always a scrappy one — but I love it.

I went to the School of Visual Arts in New York, and I always thought that I would move to LA immediately upon graduating. I didn’t think there was gonna be a robust enough animation scene to make the career that I wanted in New York.

But, while I was still in school, I was lucky to pick up a job here and there. Animated on a couple Liquid Television spots. I got some experience there, made some connections.

Initially, Beavis and Butt-Head was done at J. J. Sedelmaier’s studio. They brought it in-house for the second season. So, they were building that studio at MTV Animation, and they were really hiring. I started the day after I graduated, and worked as a board revisionist on The Head and Beavis and Butt-Head. Then ultimately a board artist on them, and directing on Daria and Beavis and Butt-Head.

And freelance work. MTV and Jumbo were the big series studios, and Nickelodeon was starting to do Blue’s Clues and other stuff in-house, but there were a lot of commercial studios in town. One I worked with a lot was RadicalMedia. I’d have storyboarding by day and animating on, like, Coke or Nike commercials by night. It was definitely helpful for my boarding and directing to have animated.

John: As someone who was in New York at that time — that gritty atmosphere that’s all throughout Downtown, that was the vibe?

Chris: Yeah. That was certainly intentional [in the show]. We wanted it to feel dirty and gritty, and not slick. Have it be kinda worn down and have a lot of texture. We were really trying to do some ambitious stuff back then.

Like, I was trying to have more full animation. Didn’t always work on the show — we tried our best [laughs]. But, yeah, same with the backgrounds. We had an ambitious thing of trying to paint a lot in-house. So, we had to come up with a style that could be executed quickly.

John: Was Downtown animated in-house?

Chris: No — you know, it’s interesting. Beavis and Butt-Head and Daria were very specifically meant to have very little animation. Daria was an interesting show to direct on, because I appreciated the comedy of it, but it wasn’t particularly fun on the technical drawing side.

Because it was basically, “Never move her” [laughs]. Don’t move her arms; just keep that drawing where she’s staring straight ahead almost all the time. It worked for that show — that show’s great. But I thought, “I want to do a show with a lot of animation in it.”

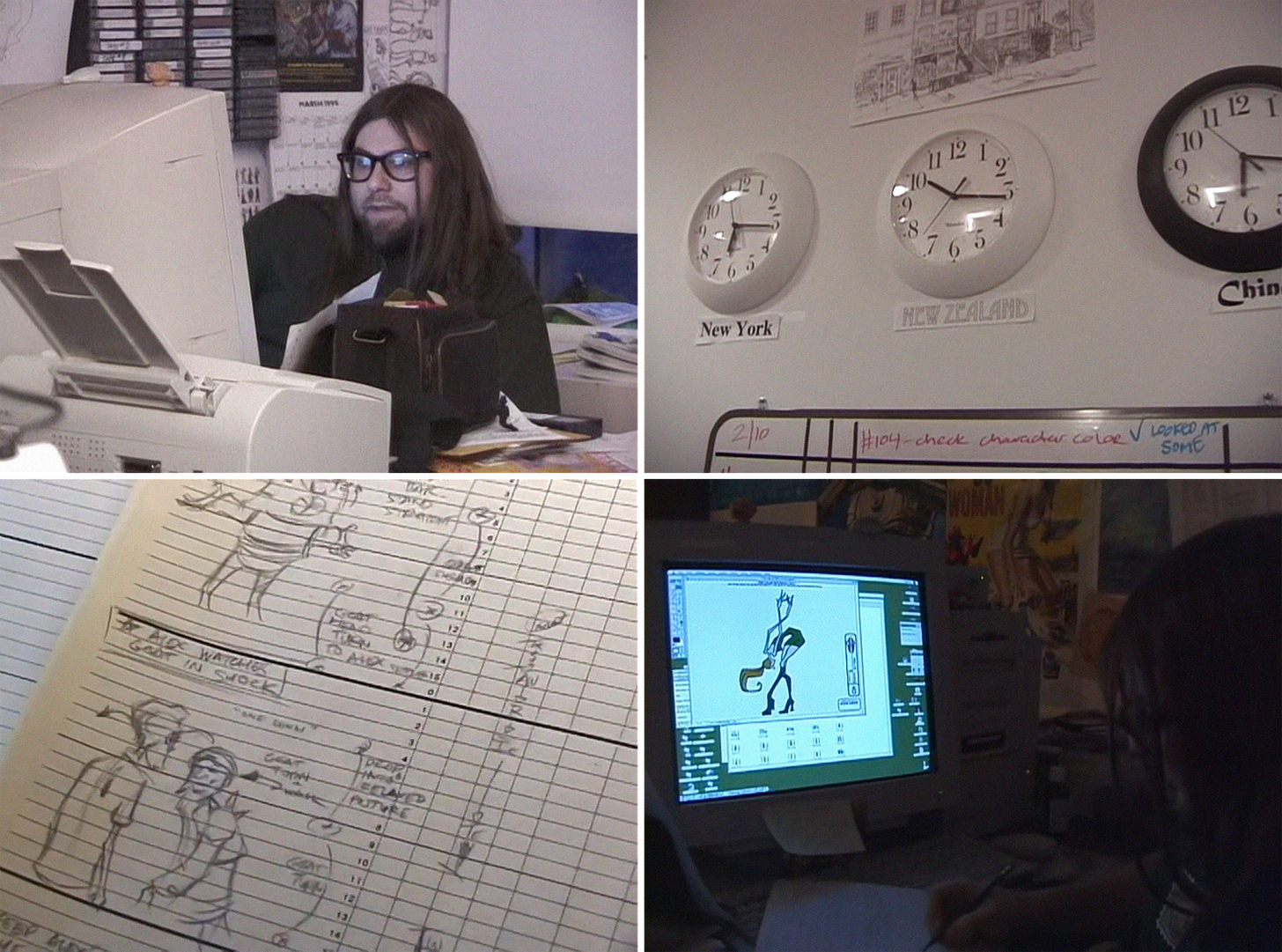

So, we didn’t do animation in-house. Every background layout was done in-house, and it would go through the directing department — there were four directors and each one had two assistant directors. I said, “The drawings don’t have to be super clean. Let’s just give the gist of it.” Some were pretty heavily posed out with layout; some were very sparse. You had to pick and choose.

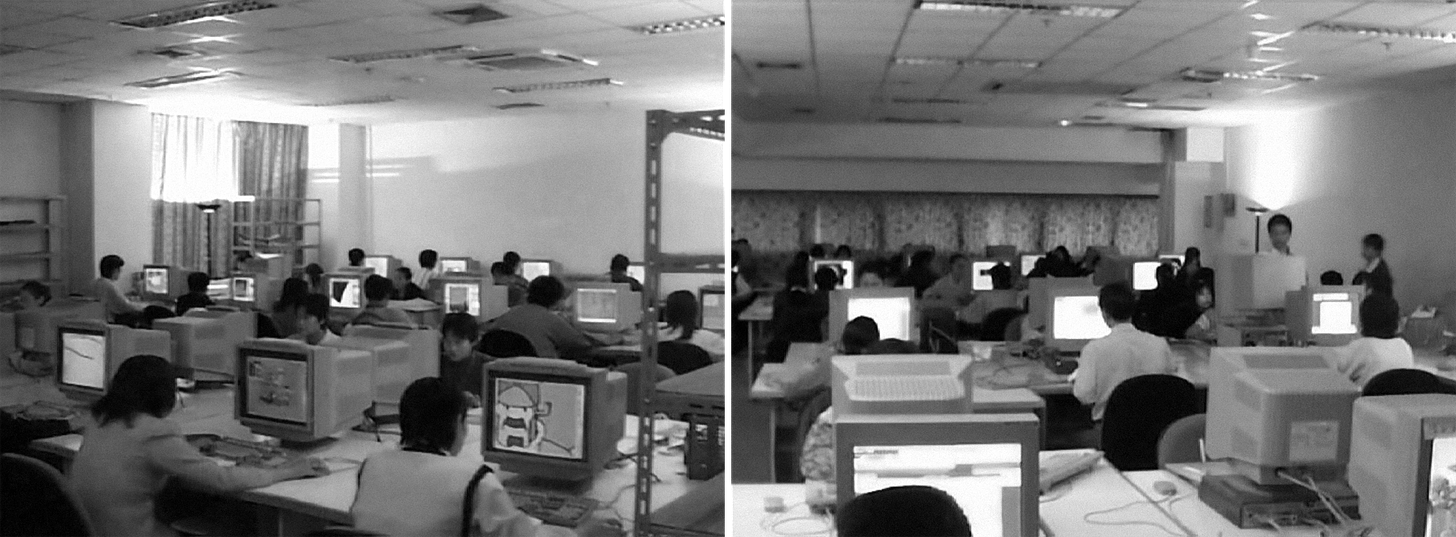

To get the fullest animation possible, rather than shipping to one of the Korean studios that generally got that work (who are great at what they do), we shipped the character animation to a studio in New Zealand that had a lot of fancy character animators. Then cleanup, scanning, coloring, compositing and some background painting were done at a studio in China.

It was the first MTV show to do digital ink and paint. We were really trying to get ambitious with color models. Now, it’s standard, but back then it was not a thing to have a different mood and color for every sequence. We did color scripts for every episode. We had two background paint supervisors, and they had a set of fancy markers they’d use to identify sequences and marker comp out on the boards.

It’s interesting — we were in that transitional thing. We still did a lot of stuff traditionally, but then everything ended up in a digital form.

John: As a final question, what memory of working on the series stands out to you most today?

Chris: Oh, man. I do think going out and doing those interviews. That was really fun. Because that’s not usually part of an animated show pipeline, right?

[Associate producer] Shane Guenego — I’m still friends with him. He was the guy often either shooting or supporting, like getting people to sign releases. It’s a grind, too. It’s your intent to talk to a lot of people, but most New Yorkers don’t want to talk. Especially back then. There weren’t people making YouTube videos or whatever. We were there with a consumer-grade video camera, so it looked like we were just a couple of 20-something dirtbags.

I’d say you had to ask 99 people before you got one. You had to be pretty tenacious. He was very helpful in continuing to push. Like, “All right. Let’s keep going.” Because you’d get discouraged after a while — “nobody wants to talk to us.” Or you talk to somebody and they’re boring [laughs], which happens, too.

But yeah, that process. Because that’s something I haven’t done since. That show was so specific.

We’d like to thank Chris Prynoski for his time. As far as we know, Downtown isn’t streaming anywhere — but the whole series has been sitting on YouTube for almost a decade. You can check it out (or revisit it) there.

2 – Newsbits

In America, The Animation Guild is preparing to fight for a new, better contract with Hollywood — to protect jobs from AI and other threats. A weekend industry rally drew a “huge mass” of people, reports Cartoon Brew.

Felix Colgrave, the Australian animator, shared a mind-bending traditional piece on paper.

In Cuba, ICAIC has been sharing films from its back catalog on YouTube. Among them: The Grateful Fellow (1966) by Tulio Raggi, plus its 1990 remake. Both are wild exercises in cartooning — in two different styles.

In Japan, Pete Docter spoke to Hayao Miyazaki on the Ghibli Covered in Sweat show. One subject was the use of feedback from test screenings — which Ghibli never does, said Miyazaki.

Also in Japan, director Sunao Katabuchi praised Oppenheimer, which played at a Hiroshima memorial. Katabuchi’s film In This Corner of the World also addresses the Hiroshima attack — he called it “significant” to show the American side there.

White Snake: Afloat, the sequel to Green Snake, is doing well in Chinese theaters. It’s already above 175 million yuan, or roughly $24.4 million. See the trailer.

American artist Mike Mignola (Hellboy) worked on an unmade Thor series in the ‘90s. Now, a short documentary tells the story and shows his concept drawings.

Another story from America: Cartoon Network’s unraveling continues with the closure of its website.

Quan Hongchan, an Olympic gold medalist, drew attention in China when she admitted to watching the animated series Battle Through the Heavens. Her big complaint: it updates too slowly.

Lastly, we wrote about the cartoon career of Vlado Kristl (Don Quixote), sometimes called the “mad genius” of the Zagreb School of Animation.

See you again soon!

Andrea Romano, now retired, is one of the best-ever voice directors. You might recognize her work from Batman: The Animated Series, Avatar: The Last Airbender or The Boondocks.

I really enjoyed this deep dive into Downtown! Your interview with Chris Prynoski was fascinating, mainly focusing on capturing authentic '90s New York life. I loved learning about the creative process behind such a unique and iconic series. Brilliant as ever.

i have always loved animation and finally with the leaps in technology am starting to create some on my own. AO’s knowledge base and pointers really have been inspiration to me. AO has helped me to know some animation giants and heroes and to see whats possible. i want to give you a very sincere Thank You!