Happy Sunday! We’re back with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the plan:

1️⃣ Work that grabbed us at Ireland’s Animation Dingle.

2️⃣ News from around the world.

If you haven’t signed up yet, it’s free — you’ll get our Sunday issues right in your inbox, weekly:

Now, here we go!

1: Six festival highlights

In the world of animation, film festivals are essential. That was true 70-plus years ago — and it’s still true today. You reach more viewers through mediums like TV and streaming, but the festival circuit is a space for totally non-commercial creativity to be seen and rewarded. Creativity with no studio notes, no nervous shareholders.

In their own way, festivals are at least as important as Hollywood — spreading new ideas, surfacing talent and pushing animation into unexplored places. The future often starts here.

We saw it happen again this week at Animation Dingle, a key festival in Ireland. Each year, in the coastal town of Dingle, animation students and pros from around the globe gather to showcase their work. The 2023 edition, which we attended virtually, brought lots of exciting films. It’s only appropriate that some of the best were Irish.

This included our most left-field favorite of the festival: Faces by Dublin’s Dylan Michael. It’s drawn a little buzz in Ireland, even winning a televised award for visual innovation. But many in the wider world haven’t heard of it yet. That should change.

For Faces, Michael spent two years asking internet strangers to send him selfies. He gathered over 2,500 photos — using them to build a funny, uneasy and unexpectedly moving film.

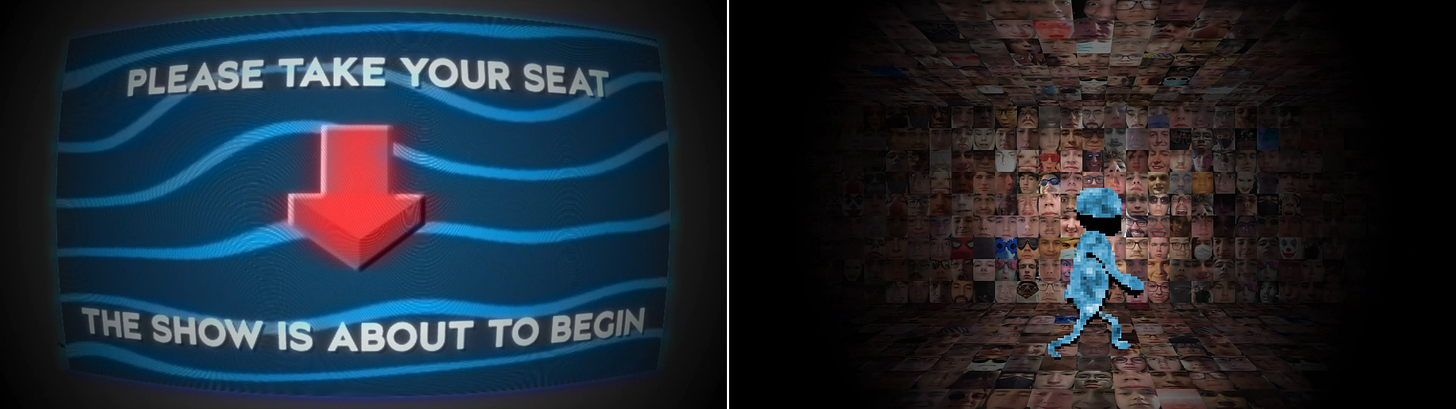

Faces is about a man named Don who wakes up in a hallway. Lining the walls, floor and ceiling are faces by the thousands. They’re low-resolution, pixelated. (In fact, the whole film looks like a corroded, no-fi shareware game from the ‘90s.) Don traverses this hallway, wondering what’s happened to him — is he dead? Then he discovers a screen that plays a movie “starring everyone you’ve ever met.”

From his creative choices, and his sense of humor and timing, you can tell that Dylan Michael is very online. The first face we see is someone in an unsettling Sonic the Hedgehog costume. Fireworks burst into masses of selfies, set to evocative piano music (which stops on a dime). Michael has the tonal awareness and just-so editing sensibility of someone who makes good memes, which he does.

What you can’t tell is that Michael was high-school age when he started Faces in 2020. He shows real maturity as a storyteller, drawing both absurdity and emotional resonance out of this warped audiovisual language. Not many can do it, yet he does.

And Faces wasn’t the only unorthodox student film we saw at Animation Dingle. Another that jumped out at us was Friendly Fire, a piece from Israel that won a top award at the festival. Animator and street artist Tom Koryto Blumen, plus a handful of assistants, painted the film on the West Bank barrier.

Friendly Fire is a stop-motion piece animated at human scale. As one official summary reads, “The film was painted frame by frame on the wall and became part of the ongoing conflict by staining it with over a hundred liters of paint.” It took from October 2021 to July 2022 to complete the project.1

If you’ve seen The Wolf House, you have a general idea of what’s happening here. The artists painted paintings and then painted over their paintings, photographing as they went, to create the illusion of movement. (Blumen has behind-the-scenes footage.)

Several times, though, Friendly Fire stops animating to reveal itself for what it is: protest graffiti scrawled across the West Bank wall.

The film begins when animated “IDF soldiers and Palestinian kids engage in a spontaneous kickabout,” noted The Jerusalem Post. Minor Palestinian victories are met with overwhelming force by the military, which begins firing soccer balls with rocket launchers and tanks. The scenario feels all too familiar. Here’s the Post again:

… Koryto Blumen manages to convey a sense of the absurdity of the human condition in our neck of the woods and the esprit de corps hovering beneath the surface. Still, there is no attempt to disguise the ugliness that is, sadly, a regional staple, too.

Even so, the brutality is tempered here — Friendly Fire puts across a forceful message without pulverizing the viewer. Matched with its visual method, the film feels destined for popular success once it’s more available.

On the other hand, we have In His Mercy — one of the most unrelenting pieces we saw this week. It’s a powerful film, but something of a white-knuckle watch.

In His Mercy comes from Germany. Director Christoph Büttner did it as a film student in Brandenburg. The process was long, painstaking — maybe four years of work, as he outlined in an interview. But what he made is a marvel: the most authentic-looking attempt at an animated German Expressionist woodcut we’ve ever seen.

The film adapts an old French horror story, The Torture of Hope, about a prisoner sentenced to death and the mental game that his captor plays with him. The atmosphere is oppressive — the expressionist woodcut style, thick with black ink, leaves little room to breathe. You feel like you’re trapped right there with the prisoner. Yet the compositions are frequently stunning, even beautiful.

While In His Mercy looks like a woodcut (it was inspired by the art of Regine Grube-Heinecke and Karel Štěch), it wasn’t made with woodcutting. Büttner developed a method with computers, as he explained:

My first attempt rendering everything in 3D was not very convincing. After some time I tried to rotoscope 3D animations I had playblasted in Maya and ended [up] with a 2D animation consisting of clean white lines. To get rid of the digital look I used a VFX process that has been partly prototyped by a smart co-student of mine. It allowed me to imitate the ink dispersion into sheets of paper, as it happens during analogue printing.

Imagine the 3D-to-2D pipeline behind I Lost My Body — only abandoning all realism.

Besides In His Mercy, another German film we need to praise is I’m Not Afraid! by Marita Mayer. It’s the polar opposite of Büttner’s piece in almost every way.

Marita Mayer hails from Hamburg, Germany, although she’s since moved to Norway.2 I’m Not Afraid! was a co-production between the two countries — a full-fledged studio film, albeit a small one. It’s aimed at children and done all in rich picture-book colors, shapes and textures.

It’s the execution that makes I’m Not Afraid! great. Creating a bad kids’ film is easy, and creating a good one is hard — even when both projects start from the same idea. Here, a young girl named Vanja wears tiger pajamas and is scared of the dark.

But what makes the film work is, for example, the voices. They tend to be raw and naturalistic, bringing to mind work like Funny Birds or Windy Day. Or take the larger-than-life storybook layouts, or the personality conveyed in the motion (an animated sniff, a nervous turn). Not to mention the UPA-style graphic ideas — like the way Vanja imagines a jungle popping out of the ground around her like a pop-up book.

I’m Not Afraid! is Marita Mayer’s solo debut as a director, after years as a producer and festival manager. It’s gotten well-earned nominations at festivals like Oberhausen and the Berlinale. We’re impressed, too. This isn’t just a great kids’ film — it’s a great film, full stop.

Meanwhile, Swallow Flying to the South is another standout film about kids. Only it isn’t for them. It’s over 17 minutes long, and slow. The viewer has to live every moment. Director Mochi Lin made this piece as a student, and she took a risky approach for a young filmmaker — the kind of approach that exposes your weaknesses. She more than rose to that challenge.

Swallow Flying to the South is a stop-motion film set in the China of 1976, at the tail end of the Cultural Revolution. It’s a tribute to Lin’s mother, who lived through that time. Lin herself was born in China, graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (where she made this film) and now lives in Canada. She told Zippy Frames late last year, “I hope to speak for those who are condemned to silence.”

Lin has done something bracingly unique here. Her puppets, with their 2D painted heads and 3D bodies, are fascinating to the eye — changing from every angle. And this may be the best-shot film we saw at the entire festival.

Lin owns that success. She took near-total control of Swallows — writing it, storyboarding it, designing it, building it, lighting it, animating it, shooting it, editing it, compositing it, color-grading it, sound-designing it and co-composing it. “I decided to keep everything to myself because of how personal and cultural-specific this story is,” Lin told Zippy Frames.

Even for her, that was a struggle. Her film is set in a strict Maoist preschool, a microcosm of the regime, that needed to reflect her mother’s experiences. As Lin said:

Preschools during the Chinese Cultural Revolution were not well-documented under camera. I read a book called Preschool in Three Cultures, written by three anthropologists in the ‘80s. Other than that, there were hardly any published resources. I confirmed details with my mother through numerous calls: the material of the chamber pots, the patterns on the roof tiles and just about everything, as I never lived through that era.

Sound design was more difficult in this regard. Many sounds are simply “lost” — the street peddlers, the pigeon whistle, certain tunes and speaker sounds during the Cultural Revolution, just to name a few. I was not able to find them in the public domain, and they are not even heard of anymore in present-day Beijing. Fortunately, my father discovered a physical “Beijing sound museum” in a tiny Hutong, and I was able to get some of my sounds from there.

That kind of attention to detail makes Lin’s film. Despite (or maybe because of) its slowness, we were mesmerized.

And now we’ve reached our final pick from Animation Dingle. It might be our film of the festival, even though the competition was stiff.3 It’s Regular Rabbit by Eoin Duffy, an Irish filmmaker based in Canada.

Duffy has made films for years, including popular ones (The Missing Scarf). But Regular Rabbit is taking him to a new level of notoriety. He’s even landed a competition slot at Annecy 2023, his first for that festival. It’s no shock, though — this is a hilarious black comedy unlike any we’ve seen lately.

Supposedly, Regular Rabbit is about what its title suggests: a cute rabbit in the woods. As the narrator says toward the start:

This is a rabbit. A regular rabbit. That is to say that this is not an evil rabbit. He is simply a rabbit. A regular rabbit. Of course, we must mention the incident…

The conceit here is ingenious. Throughout the film, what the narrator says and what we see rarely match up. The so-called regular rabbit hops around in the woods, looking harmless enough. But the narrator weaves an unimaginable tale about him, full of murder and madness. It creates a disconnect that’s instantly funny.

As he planned Regular Rabbit, Duffy asked himself:

How comically large can the distance between imagery and narrative be pushed? I decided to pair the most innocent inculpable visuals with the most heinous storyline possible. Straightforward scenes of a rabbit, next to a spoken story of barbaric sadism. No apparent links between the two.

It makes you think. More than that, it makes you laugh. Regular Rabbit is one we keep talking about. There were excellent films at Animation Dingle 2023, including many we didn’t mention here — but, for us, Regular Rabbit is way up there. We wish it luck at Annecy this June.

2: Newsbits

We lost Raoul Servais (94), a legendary director in Belgian animation — among many other things. See AWN for more.

In China, Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume is a record-shattering hit, earning over 300 million yuan (around $43.6 million) in three days. It’s already close to the lifetime earnings of Your Name (575 million yuan), despite forecasts that it would only draw 200-to-300 million total. Some industry watchers attribute the success to Shinkai’s extensive press tour of China, which began in mid-March.

Canadian animator Denver Jackson is having success on Kickstarter with his feature film The Worlds Divide. He animated it himself over the course of two years — he notes that he worked 14-to-18-hour days, seven days per week.

A preview sequence from the upcoming French feature Chicken for Linda! has emerged via the paper La Croix.

In Ukraine, Mavka: The Forest Song has become the highest-grossing domestic film since the country won independence from the Soviet Union. It’s earned UAH 81.8 million (around $2.2 million) in Ukraine after three weekends.

For anyone interested in the Japanese studio Mushi Production: the historian Toadette has a new, book-length article about its series New Moomin, and Matteo Watzky (Animétudes) is publishing a large-scale dive into the company’s history.

In Mexico, the studio El Taller del Chucho (Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio) opened public slots in its stop-motion training program.

In Japan, Tonko House and Dwarf Studios are teaming up for a new stop-motion short called ボトルジョージ (literally, Bottle George). Dice Tsutsumi will direct and co-write it.

If you’ve ever wondered how European animation is marketed, including the French film Little Nicholas, Cineuropa has a detailed piece about it.

Lastly, we looked at Hayao Miyazaki’s guide to running.

Until next time!

Detail from Blumen’s LinkedIn page.

Today’s issue was whittled down from a longer list. We really enjoyed films like Still Up There by Joe Loftus, Stan by Me by Rachel Dixon, The Record by Jonathan Laskar, The Presenter by Josephine Lohoar Self and Another Presence by Simon Ball, to name a few. The whole Irish Professionals section was well worth watching, too.

Another succinct and well-written piece. I am really enjoying broadening my knowledge. Thank you.