Happy Sunday! We’re here again with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is the plan today:

1️⃣ On Run, Melos! — a buried treasure of realist anime.

2️⃣ The world’s animation news.

Before we continue — readers power this newsletter, and we’d love for you to join us:

With that, we’re off!

1: Anime realism

Run, Melos! is an obscure one. It’s a theatrical anime feature from 1992 that, even in Japan, hasn’t had a proper re-release since the LaserDisc days. We were shocked when we first stumbled upon it — both because we’d heard so little about it, and because it’s really, unexpectedly good.

Melos breaks away from the cliches of anime. You won’t find a trace of high school or superpowers here. It’s set in the ancient Mediterranean world, and its focus is, above all, on realism. This was an ethos, a philosophy about what Japanese animation could be. The film’s director, Masaaki Ōsumi, said in 1992:

We still can’t compare to Disney at fantasy, but Japanese realism anime far exceeds the world standard. If that’s the case, you make the most of it by carefully avoiding conventional anime patterns. … Run, Melos! was an ideal subject for such a film.1

There’s a debate over what, exactly, the major discovery of “anime-style” animation was. Some say it’s abstract, kinetic movement — or pushed character emotions. When you hear anime, either might come to mind. Those things weren’t exactly new, though. American animators like Jim Tyer had done the kinetic stuff, and extreme emotions were a Rod Scribner staple on countless Warner Bros. cartoons. Anime might have popularized them, but it didn’t invent them.

But Ōsumi was on to something. What anime can claim as its own is the perfection of animated realism. It’s not just the sense that you’re watching live actors, like in Snow White. It’s the conjuring of a stable, studied, three-dimensional world — populated by unusually detailed characters and objects, whose movements defy the rules of cartoon motion and pacing. It all feels solidly, tangibly physical.

“There’s the Disney style, an elastic animation with deformations,” as the French director Christian Desmares once said, “or a more rigid and realistic style, like the Japanese.”

You see it in Porco Rosso’s planes, and in so much of Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away. It’s in the films of Katsuhiro Otomo and Satoshi Kon. It suffuses Magnetic Rose, Grave of the Fireflies, Arrietty and scene 20 of Innocence. The characters are stylized, but everything has a natural, full and concrete quality that’s different from traditional cartooning.

And this is what Run, Melos! has in spades.

Run, Melos! adapts a short story by Osamu Dazai, a Japanese author from the 20th century. By the time this film premiered, Dazai’s original was widely known in Japan — the kind of thing that everyone had read in school.

The gist: a rural peasant named Melos is sentenced to death by the ruler of Syracuse. Melos begs to be allowed to attend his younger sister’s wedding back home before his execution. As collateral, his friend Selinuntius (shortened to Seline in the film) gets put in his place. If Melos doesn’t return in time to be executed, Seline will die.

It’s a classic. But Masaaki Ōsumi, who wrote the screenplay as well as directed it, took liberties with the original short story. He wondered, “Why did Seline become a hostage so easily?” In Dazai’s version, it’s unexplained. Ōsumi wanted more realism.

And so he began to think of a new spin, where Melos is a hapless innocent and Seline is worldly and jaded. They’ve just met in the city, but Seline puts his full trust in Melos — a final, life-or-death bet on human goodness. Ōsumi called it a “modern interpretation,” a response to the loneliness and isolation felt by so many in ‘90s Japan.

Ōsumi envisioned Melos as a film with a complex cast, believable human drama and real answers. Additions like the character Raisa helped this along. The magazine Animage noted that she fell outside the anime archetypes of the day — Ōsumi believed that “modern women will understand her.”

By the time of Melos, Ōsumi was a veteran. He’d overseen the Moomin series in the late ‘60s and Lupin the Third in the early ‘70s (before Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki took it over). He was known to direct with words rather than images — he understood filmmaking, but he didn’t storyboard. Animator Yasuo Ōtsuka once said:

Ōsumi-san uses a lot of words. It’s like this, it’s like that, this is interesting, this is fun. I was amazed by his ability to persuade storyboarders and animators with so many words.

But anime is a visual medium, and Ōsumi needed artists to turn his ideas into pictures. On Melos, his right-hand man was Hiroyuki Okiura: the lead storyboarder, character designer and animation director.

Okiura is respected today for directing Jin-Roh (1999), but he placed that film neck-and-neck with Melos when naming his favorite projects in 2005. Melos was “very significant,” he said. Working with Ōsumi changed the course of Okiura’s career.

As an animator, Okiura was a budding hyperrealist. He’d come from projects like Akira and Roujin Z, having animated much of the latter film’s climactic sequence. But the realism Ōsumi wanted for Melos — which extended not just to the story but to the images — was a challenge. Okiura wrote:

Surprisingly, when it comes to realistic characters who are a relatively large number of heads tall, there hasn’t been a work that focuses on everyday-life acting before, and that was the hardest part for the animators. Even acting that’s easily done with a slightly deformed character takes a lot of drawing power to do realistically, so it was more labor-intensive than expected. The same was true for the animation direction work, which took twice as much time and effort as usual.2

Given the team involved, that’s saying something. On staff were animators like Hiroyuki Morita (director of The Cat Returns), Mitsuo Iso (Only Yesterday, Perfect Blue) and the unbeatable realist Toshiyuki Inoue — who also helped with the animation direction.3 It took a group like this to handle the demands of Melos.

And it’s hard to imagine an artist besides Okiura himself holding together Ōsumi’s vision for the film. He took endless notes at their meetings, chasing the director’s flow of words. “I tried to work according to the image of Director Ōsumi as much as possible,” he wrote. Okiura’s superhuman drawing ability became Ōsumi’s conduit — in the storyboards, and in the character designs.

When Okiura made his first character sketches, they got a note from Ōsumi: “more Greek-like.” The director insisted that the cast look Western, citing the differences in bone structure between Japan and the rest of the world. Ultimately, only Melos had somewhat Japanese features, Okiura said — to keep him relatable to the audience.

The backgrounds, supervised by artist Hiroshi Ōno, were another story.4 The director gave Ōno just two key orders: realism, and a focus on light and shadow.

To make the world of Melos true to life, the team took scouting trips to the Mediterranean. People think of Greece as a bright, white place, Ōno said — but it was brown when he visited. Brown became a core color in Melos, even for the grass and sky. It adds what Ōno called a sense of “dustiness and high temperatures.” To capture that contrast between light and dark, he chose shadow colors that were almost black.

It mattered for storytelling reasons. As Animage noted:

Contrast and light source are major points of the work. In an era without clocks, developing a story that emphasizes time can only be done through the position of the sun and the presence or absence of torches. In every scene, this is made clear.

It was one of the many ways that the historical era of Melos, around 360 BC, guided the background staff. Ōno and his artists aimed for accuracy, capturing the architecture and landscape of the region. Their work on the film has a specific, hand-crafted attention to detail rarely seen in anime backgrounds today.

One of the artists making it happen was Satoshi Kon, who did layouts for Melos. They’ve got the tangible feel that later characterized his own films. This was only his second job in anime — he was fresh off Roujin Z, following Okiura from that project to this one.5

Animator Michio Mihara remembered that he and Kon would, during Melos, go out drinking until the early morning, as Kon ranted about the anime and manga business. But Kon’s work still shined. Toshiyuki Inoue praised his layouts for the film, as did Okiura. Kon’s drawings guided not just the background paintings, but the animation.

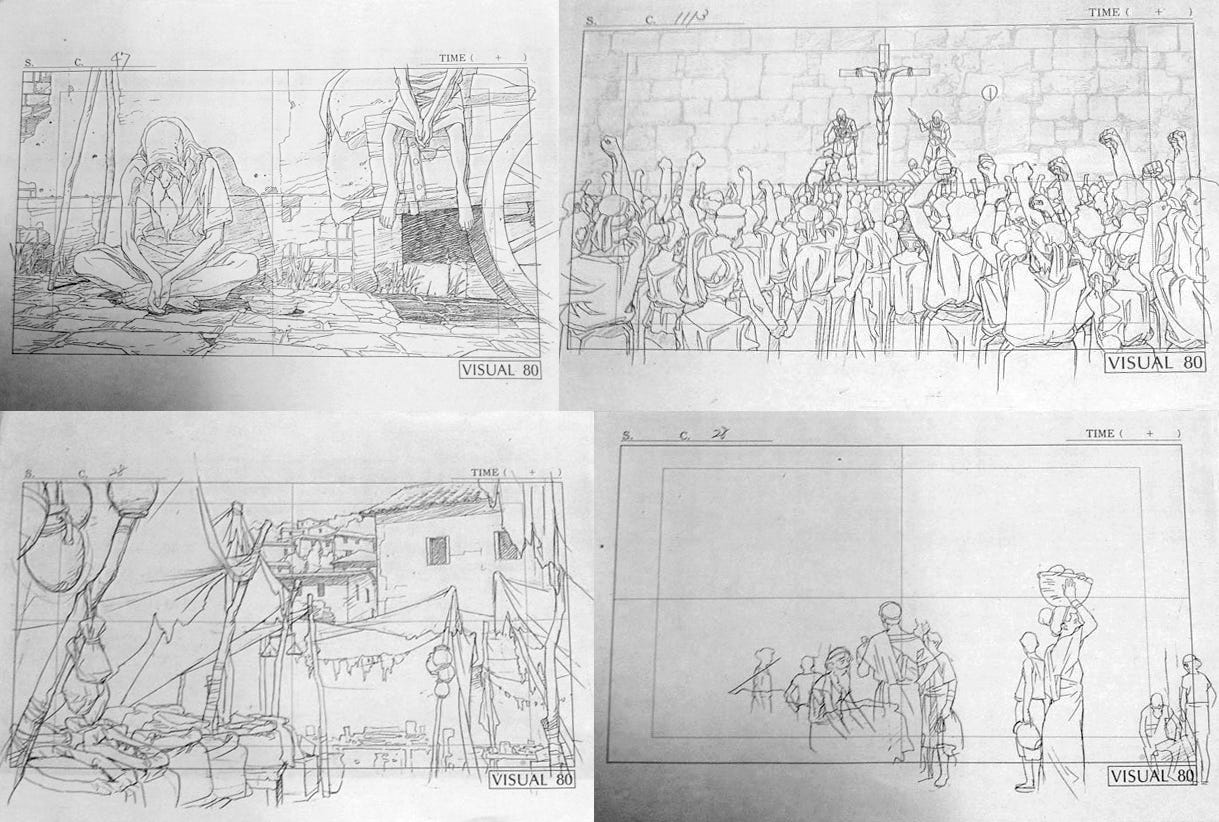

“One of the most impressive parts is the mob scene at the end,” Okiura said, “where Kon-san’s taste remains even in the characters.”

Run, Melos! is embedded above, with optional English captions. As a note, there are adult elements in it — bloody violence, mild nudity. But it’s nothing like the exploitation anime that was popular at that time.

In one of the standout action scenes, when Melos is ambushed in the woods, Mitsuo Iso took charge of the key animation. But the team purposely dialed back the fight so that it didn’t “become too flashy,” according to Animage. There’s excitement in this sequence — writer Ben Ettinger cited its “impressive body movement” — but it’s done with taste.

Also tasteful is the scene where Melos’ sister gets out of bed with her husband to wave goodbye from her window — a moment that could easily have felt off. Key animator Hiroyuki Morita helped to make it one of the most grounded, genuine scenes in Melos, working in tandem with the atmospheric backgrounds. For Okiura, it was a highlight of the film.

Back in 1992, neither of these scenes could’ve appeared in an animated movie made anywhere but Japan. They show, as Ōsumi said, the world-beating realism that anime had perfected.

But you see that throughout Melos. The film is stylized — but the animals and the wrinkled cloth, for instance, are weirdly lifelike. One scene toward the end, where Melos rides on horseback through a town and steals food, features key animation by Toshiyuki Inoue that doesn’t look like a live-action film but feels at least that real. Honestly, it feels more real, weightier, more visceral. A live-action film couldn’t capture it.6

And all of it is in there, first and foremost, to tell a story. The realism in Melos isn’t a technical flex: it looks and feels this way because, for Ōsumi and his team, this was the form needed to suit the content. To feel this story, we needed to feel like we had two feet in the ancient Mediterranean. We needed to feel the dust, the glare, the robes and the physical, human bodies.

This little-known curio of a film pulled it off — and, for that, it deserves to be remembered.

This is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on November 3, 2022. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — now, we’ve made it free to all.

2: Newsbits

We lost animator-director Tony Kluck (75), known for projects like Daria — and Valeriy Fomin (84), behind Russia’s Vera and Anfisa series.

In America, the story of the week is the writers strike, which is (for good reason) taking on studios in live-action film and TV. Also affected are the animated productions covered by the Writers Guild (see: The Simpsons, Bob’s Burgers).

All Those Sensations in My Belly, a Croatian film that really grabbed us at Annecy back in 2021, is now online for free.

The acclaimed stop-motion series Frankelda’s Book of Spooks, from Mexico, is getting a feature film. It has a work-in-progress showing at Annecy this year.

Speaking of Annecy 2023, the French festival is making a ton of announcements lately. Among them are this year’s feature films in competition, which include Art College 1994 by Liu Jian (Have a Nice Day), The Inventor by Jim Capobianco and Toldi by the late Marcell Jankovics.

In America, Gallery Nucleus opened its “Created by Craig McCracken!” exhibition on May 6. Artwork is now up for viewing and purchase online, too. For more details, see our extended interview with Craig McCracken from last week.

The English studio Aardman is showing off visuals from Chicken Run 2, the sequel to the most successful stop-motion film ever. It drops later this year.

In Japan, producer Masao Maruyama (Madhouse, MAPPA) says that “Japanese animation has completely collapsed.” He argues in an explosive new interview, “The best parts of Japanese animation have been lost to digital, and there is no one to carry on the tradition.”

Meanwhile, the American-Congolese-Japanese film Mfinda (in which Maruyama is involved) just picked up GKIDS as a co-production partner. It’s reportedly the third co-production by GKIDS, on the heels of The Breadwinner and Wolfwalkers.

In China, indie animators are seeing success on Douyin (the sister to TikTok), gaining millions of fans with their short animations. What started as a hobby is becoming a career for some, reports Anim-Babblers. Shades of the 2000s Flash boom.

Vaibhav Studios in India shared stop-motion process footage for one of its new Cartoon Network idents. (You can watch the final product on YouTube.)

The second season of Star Wars: Visions is out, and the episode contributed by Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon is very good. Director Paul Young spoke about it.

In Russia, theaters’ financial reports for 2022 show the effects of the war and subsequent boycotts. Industry watchers are comparing the impact to that of the COVID-19 pandemic — the country’s big theater chains lost billions of rubles.

Lastly, we looked at the living silhouettes of Lotte Reiniger — one of the all-time greatest animators.

Until next time!

From the September 1992 issue of Animage, one of our main sources. We accessed it via Anim’Archive.

From the Run, Melos! Anime Book, another important source. Historian Seiji Kanoh shared the relevant part of it here.

Inoue wrote about working as an animation director for Melos on Twitter, here and here. It was an assistant job, for which he went uncredited. He also related that Okiura kept a guide for drawing the characters, to help when correcting the other animators’ work. The weird thing: Okiura’s personal guide didn’t match the model sheets.

Ōno is another legendary figure in anime, having supervised the backgrounds for Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Satoshi Kon wrote a little about his time on Melos on his blog.

I've always been into this "stylized realist" style in anime - it never dominated the anime industry but from the late 1970s - early 2000s it was a rare and interesting treat that could be found in prestige projects.

I kind of feel like the origins of it can be traced back to the Isao Takahata's world masterpiece theater shows of the 1970s esp. 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother which pulls heavily from Italian neo realism. I feel like the style hit its absolute peak with Okiura/Oshii's "Jin-Roh", but then quickly started to fade away after that. Even Satoshi Kon's was starting to move in a more surrealist direction with Paprika and I could see an acceleration of that trend with the art released out of his never finished film "Dreaming Machine" -even Takahata himself abandoned it with 1999's "My Neighbor's the Yamadas" never to return again in his career.

One of my biggest frustrations with modern anime is that this sort of film just isn't really made anymore. I think hints of it survive with Yasuhiro Yoshiura's work (esp his short "Bureau of Proto Society" from the Japan animator expo) but its just not a thing anymore. I miss this sort of realism and mature storytelling that tended to accompany it.

(I accidently posted this on the older version of this article, put it here instead)

I love that story. Although I have only seen the Fuji TV 1980 version. It will be interesting to see the 1992 too.