Craig McCracken on Creativity

Talking to the 'Powerpuff Girls' creator in honor of his new solo exhibition.

Happy Sunday! This is a special, extended issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter: a conversation with Craig McCracken on process, design, storytelling, inspiration and his new gallery show.

McCracken is a cartoon legend. He made The Powerpuff Girls in the ‘90s and has stayed consistent with each series since — from Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends to Wander Over Yonder to Kid Cosmic. This year, the Annies handed him a Winsor McCay Award for lifetime achievement, putting him in the company of Hayao Miyazaki and Mary Blair.

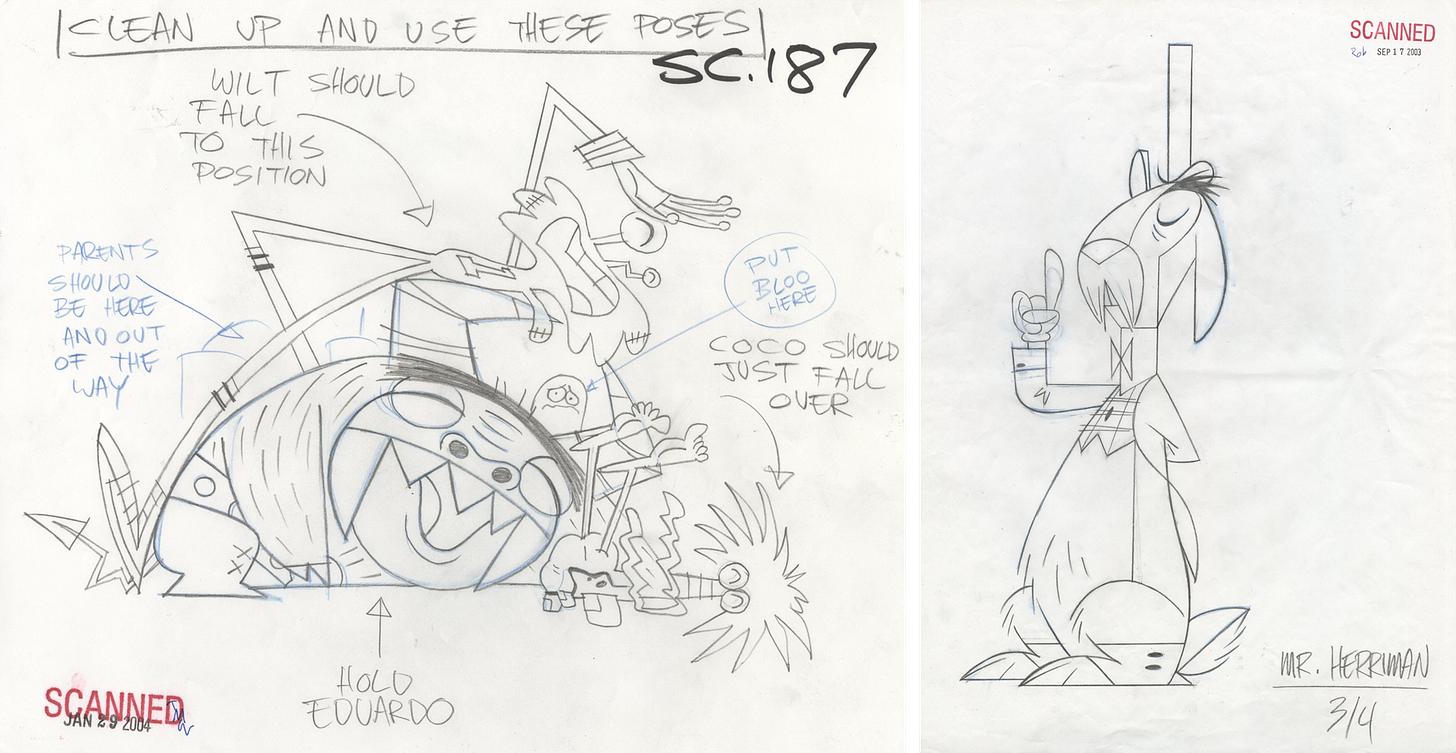

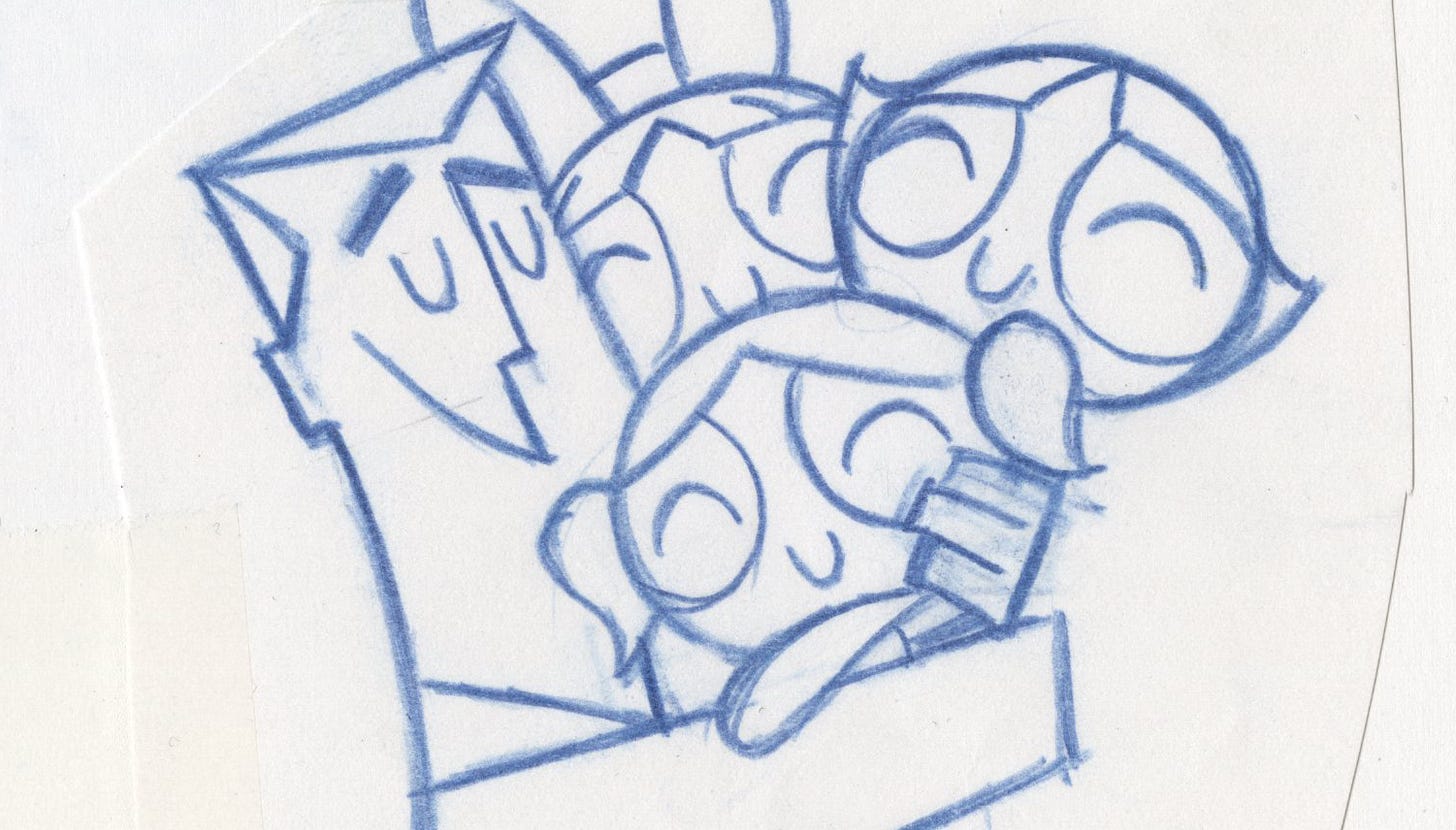

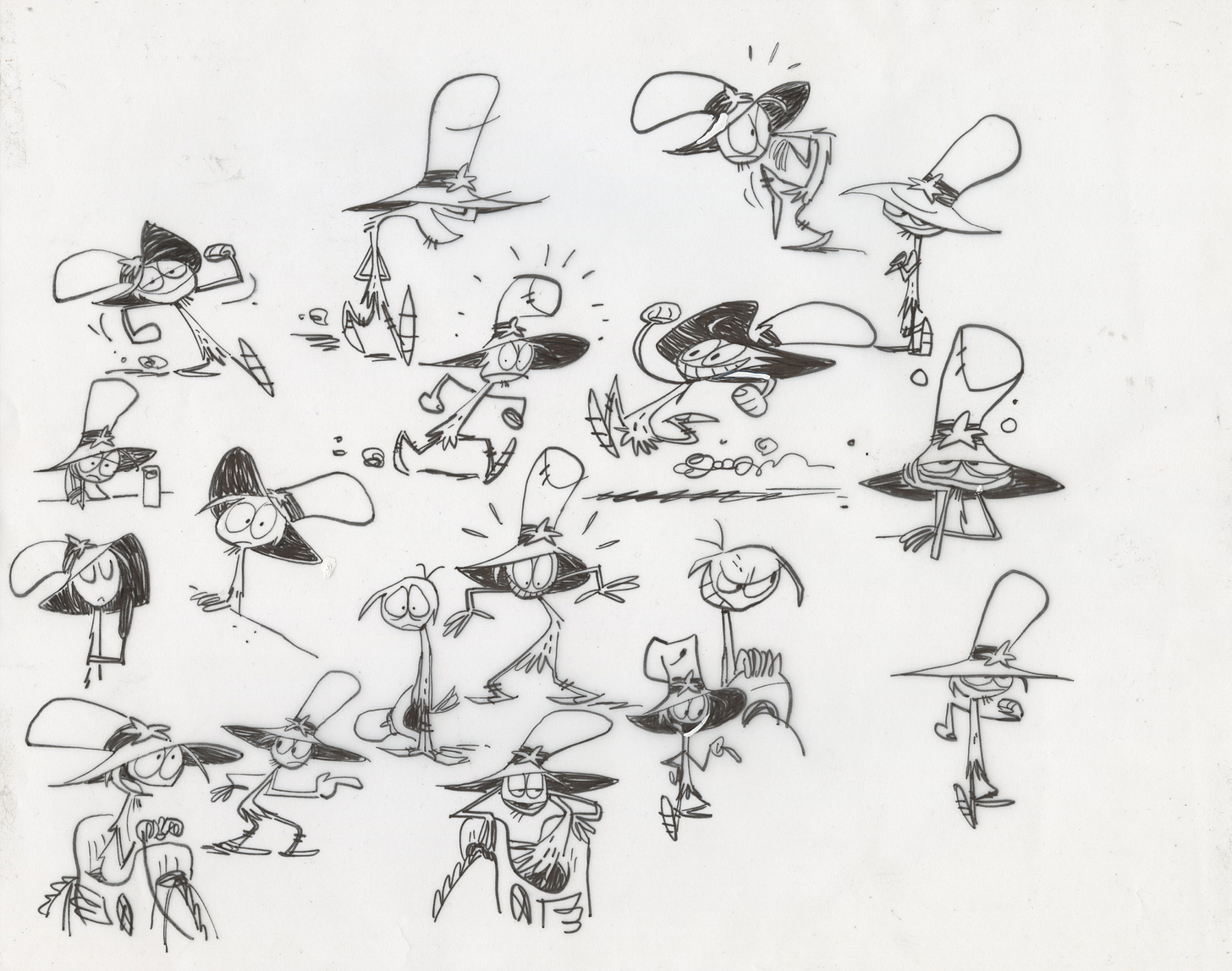

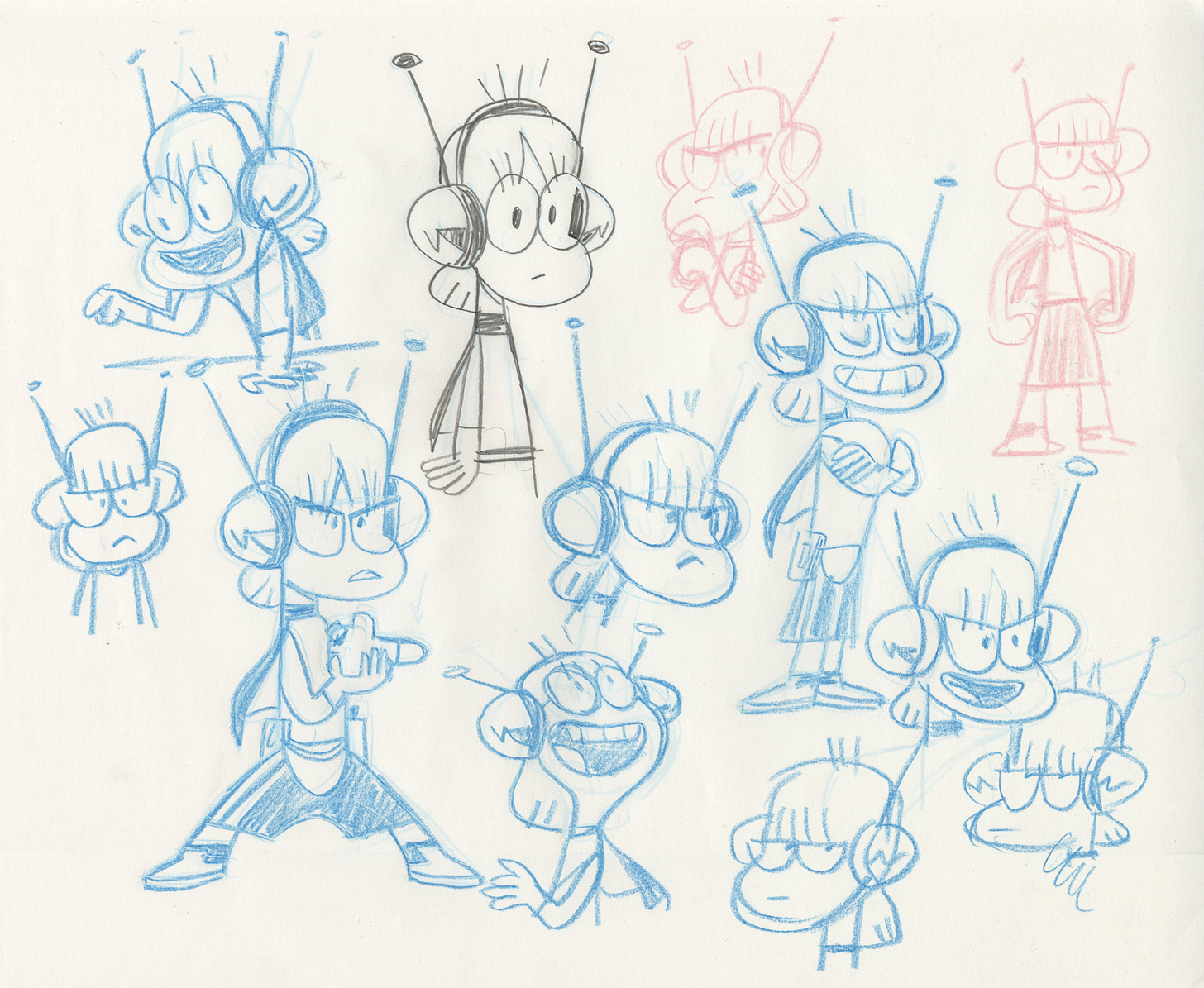

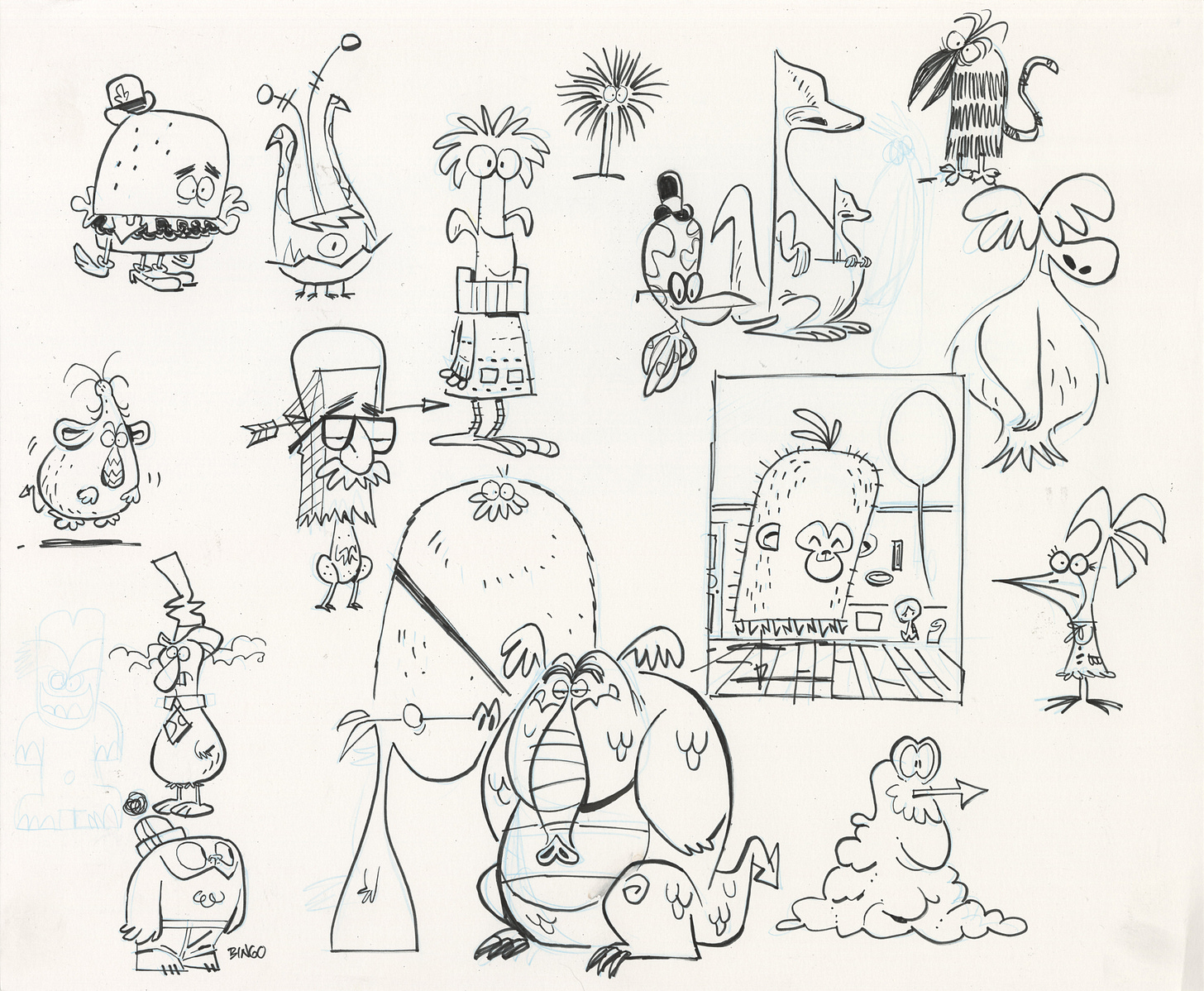

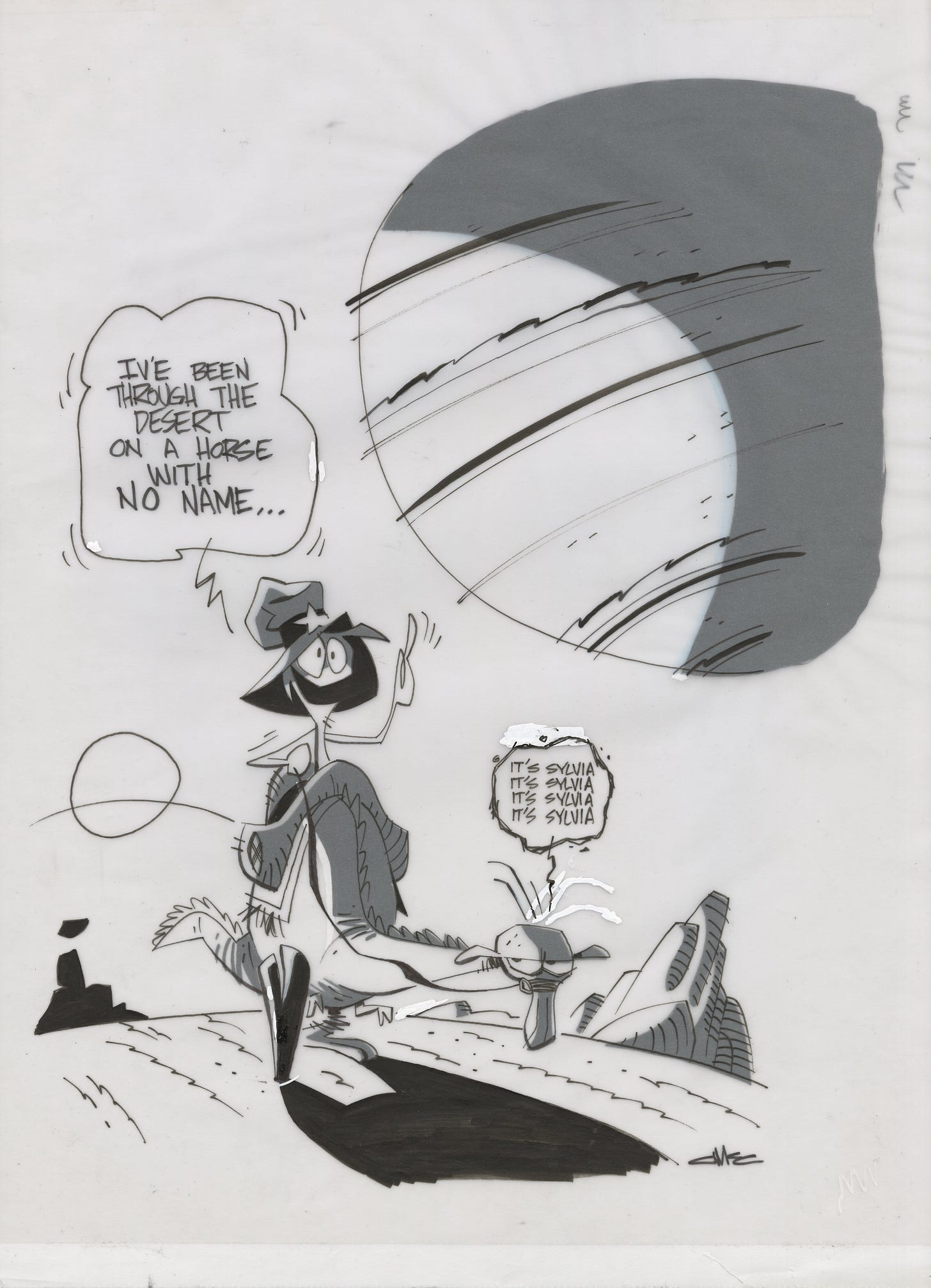

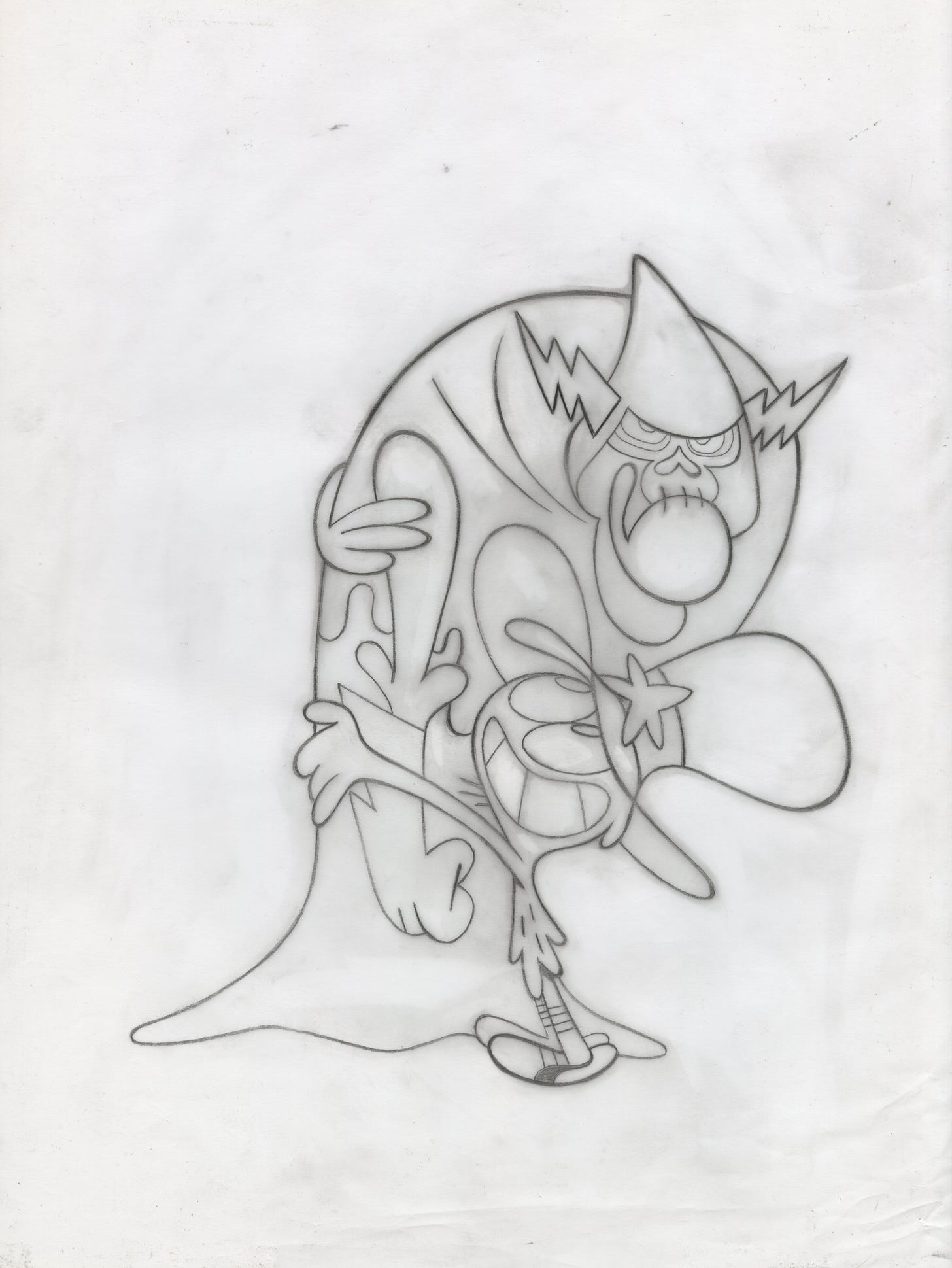

Now, starting May 6, McCracken has a solo exhibition at Gallery Nucleus in Alhambra, California. It’s a selection of art from his personal archives — from across his decades in animation. “This is kind of the first time this work has been seen and available for viewing and purchase,” he told us.

The show is called Created by Craig McCracken! and it runs until May 21. Admission is free (barring two paid events scheduled for the 13th). Find more details via Gallery Nucleus.

In the lead-up to the show, our teammate John spoke to McCracken by phone about his artistic practice, taking a long look back across his career. To illustrate the interview, we asked Gallery Nucleus if we could use artwork due to appear in the show — and they sent us scans of a dozen pieces that will be sold there from McCracken’s archives.

We’re excited to share McCracken’s insights, and his art, with you today.

John: I’m going to start off with a relatively simple, straightforward question that may actually be more complicated than I think it is.

Craig McCracken: Right, right.

What makes a great drawing for you? When you draw something and go, “I like this one.”

Something that expresses tons of character and is very simple and clearly drawn. Just, like, simple personality communicated without a lot of extra detail — the most basic design that really communicates a personality or an attitude.

Is that a definition that’s changed for you over time?

No, I think that’s just why I’ve always been drawn to cartoon images, ‘cause cartoon images are designs that are distilled down to the essence of a character. You know, Mickey Mouse is the perfect example of that — with a few simple shapes, you can get tons of personality and attitude. And I’ve been drawn towards cartoon images since I was, like, a baby. There was just something about them that really appeals to my brain, so I like simple cartoon imagery that communicates attitude and behavior.

Also, I think maybe some of it is, I’m a real visual thinker. I understand stories better with pictures; I understand films better that are visual storytelling. Sometimes, if there’s a lot of dialogue, I kind of tune out. But, if the pictures are telling me what’s happening or if the pictures are telling me how a character is feeling, then I can understand what’s going on. That’s why I think I gravitate towards cartoons.

And so, when I’m doing my own stuff, that’s what I’m looking for. Just simple communication of personality and behavior.

Right, right. That makes perfect sense. So, that leads into my next question, which is: who were your early artistic influences? You mentioned Mickey Mouse, even when you were young.

Yeah. Even though I’ve spent my career in animation, I was more drawn towards comic strip artists or print cartoonists. So, people like Charles Schulz, Bill Watterson, Hergé — who did Tintin. There was a Mickey Mouse comics artist in the ‘30s named Floyd Gottfredson. I always loved his work. But, yeah, comic strip artists were my favorite cartoonists growing up. Because, like I said, all these characters were distilled down to their essence. E. C. Segar, who did Popeye, you know, I just love those types of artists.

I’ve read in previous interviews that you didn’t necessarily know the mid-century style by name, the sort of UPA type of look, when you were younger — but it was something you were drawn to?

Yeah, I mean, I grew up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, right, where there’s no YouTube. Or even no internet, for that matter. There was no way to easily access this stuff. But I kinda had vaguely seen advertising art from the ‘50s and ‘60s, and knew that there was a studio or somebody who did these really graphic cartoons.

And you’d see it in certain shows. You’d see it in Hanna-Barbera cartoons; you’d see it in Underdog or Rocky and Bullwinkle. That very flat, graphic, mid-century design. But I had no way of accessing it. I was just, “I know there’s this thing out there, but I don’t even know where to go to find out about that.”

Getting into CalArts, that’s when I learned, “Oh, it was this studio called UPA, and they did all these independent films, and then they did all these commercials, and that’s where that kind of look came from.” I didn’t even know animation directors when I was in high school. Like, I had read the name Chuck Jones, but I didn’t know who that guy was, the exact studio that he worked for. It wasn’t until I got into school that I learned the whole history of it.

But, yeah, I was always vaguely drawn to that really graphic look that you saw in Hanna-Barbera shows and Total Television’s Underdog, and Rocky and Bullwinkle. I just like that super clear, simple cartooning.

Right. So, when it comes to learning about UPA at CalArts, did you speak to any of the old UPA guys who were there?

I know Jules Engel was there,1 but the only interaction I had with him, and I didn’t really speak to him, is… he was in the experimental animation department. He led that department. He did come up and give a lecture on Gerald McBoing-Boing, and walked through his color theory of why he did everything and what choices he made. So, he screened it for us and walked through his thought process, and that was just enlightening and fascinating.

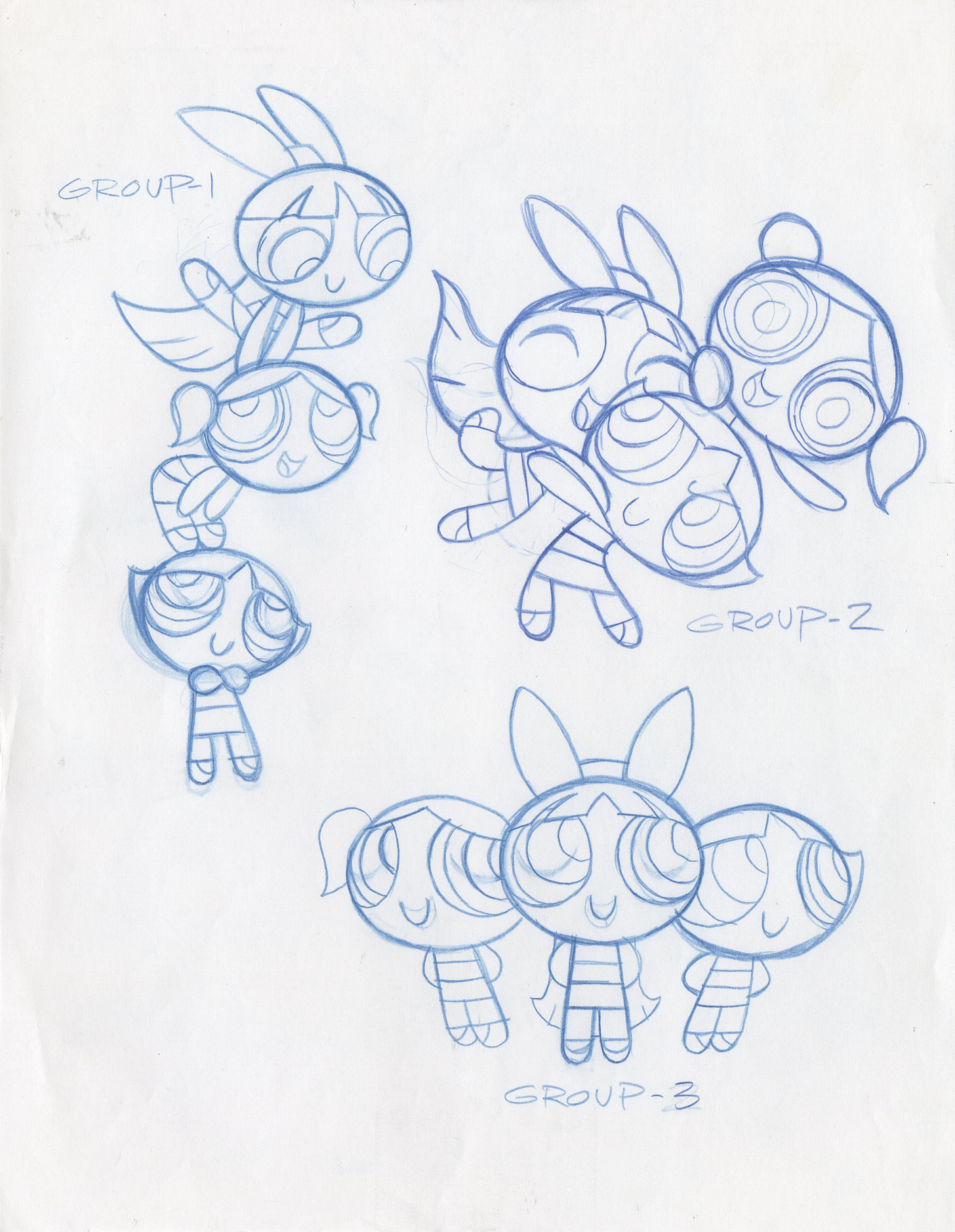

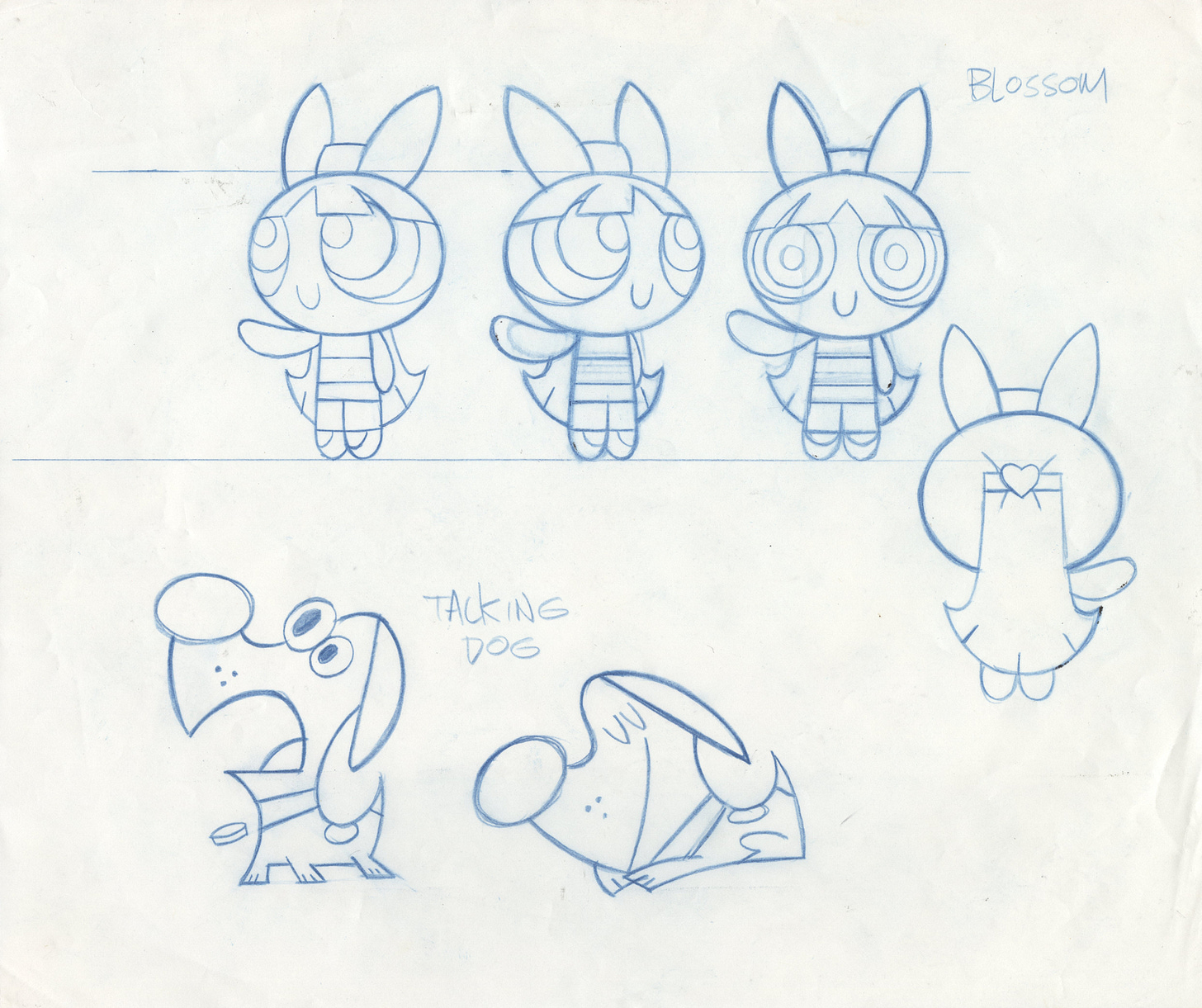

When it comes to this flat, graphic, very shape-driven type of drawing… you know, shapes are really important to your art and they have been for a long time. If you look back all the way to the early Powerpuff model sheets, there’s a note that says the girls’ heads aren’t like a ball or an egg or a pill, but there’s this other shape that isn’t quite like anything else. And so, I’m wondering — when you draw, how do you think about shape?

I don’t know if it’s necessarily that I’m thinking about shape to begin with. I’m sort of trying to find the essence of a design. And a lot of it is looking for the shorthand. What’ll happen is, I might design a character that I really like. And I’m like, “Oh, I like that combination of shapes. I like those proportions.” Then one thing I do is, I just stop looking at the model and I just start doodling.

What happens is, the faster you draw a character and the quicker you draw it, you start doing these lightning poses. What naturally starts to happen is, you eliminate what’s unnecessary. Or things like proportions naturally start evolving and changing, the way it’s comfortable for your hand.2

You know, when we designed Dexter’s, Dexter was originally a lot taller. He had a really tall forehead, ‘cause we were like, “Oh, he’s got a big brain, so there needs to be room in there for this big brain.” So, he was a taller character. But the more we drew him as model sheets and in storyboards, he just started shrinking. Because it was the natural shorthand of drawing Dexter we arrived at. And then that becomes the design.

So, whenever I’m doing a new character design, I’ll get a design that I like, I’ll get the basic shapes, and then I just start doodling. And, like I said, the proportions change, the shapes either squash or stretch or get taller or whatever. Then you start finding, “Okay, that’s the essence of the design; that’s what my hand wants to do.” From that point, once you’ve found the loose, gestural version of the character, then you can retroactively go back and go, “Okay, well, what is that shape?”

The Powerpuff Girls, we just drew them and drew them and drew them and drew them, and it wasn’t till we started on the movie that I realized it was a 55-degree ellipse that my hand was naturally drawing. So, we started to implement that. Like, “Okay, so that everyone can draw them proportionately the same, we’re gonna get these ellipse templates, and we can use that.”

But the other thing is, once you’ve drawn the graphic character, especially with the Powerpuff Girls — even though they look flat, they actually have volume. You see on those model sheets where their head is this sort of “not an egg, not a ball,” the facial features wrap around that volume. When they’re looking up, the angle of the hairline or the angle to the eyes might shrink, depending on what the perspective on that drawing might be. Or the way you angle the line of the belt around the body to define their waist. Or the angle of, like, their shoes. Just to indicate volume, that they are somewhat solid, even though they look flat and graphic.

But that process doesn’t come until after I’ve kind of doodled them forever, you know?

Right. No, that makes total sense.

And that’s why we would oftentimes revise models after a few seasons, because everyone starts changing the design. And you see it in every show. I mean, SpongeBob evolves, Homer Simpson’s evolved, and that’s from the natural process of multiple artists drawing them. And they just naturally change on their own.

Yeah, no, that’s true. So, I guess when you have what you call the “gestural version” of the character, is that when you can tell that the character is starting to really work, when you’re designing it?

Yeah, when you can get their personality and their attitude down with a few short gestures, or just a quick doodle — ‘cause I don’t like characters that have a lot of, like, noodly nonsense.

[laughing]

Like, you know, belt buckles and shoelaces and stuff. It’s like, “I don’t want to draw all that!” I want to quickly get the character down and get their personality out, and express it clearly and simply. As opposed to all this extra… because then it starts becoming more of an illustration and less of a cartoon, you know?

And that’s why I like characters like Schulz’s Peanuts characters, ‘cause they are just the most minimal designs. But the proportions and the shapes and the way the line works, they’re perfect. When you do that sort of a design, they’re really hard to mess up. No one can draw Charlie Brown correctly, or Snoopy correctly, other than Schulz. Because it’s just the way his hand naturally worked. You get the proportions of the ears wrong, or you place the face too high on that shape — and, all of a sudden, it doesn’t feel like the character anymore.

So, I really like getting characters down to some sort of gestural essence, really.

Speaking of comics as one of your big inspirations, especially early on — you have worked in other mediums besides animation, off and on, a little bit over the years.

A little bit. Yeah, I drew a couple of Powerpuff comics. I did that, I did some children’s books, but not tons of it. But I love it. I really love print, because then I can change the model if I want [laughs]. You don’t have to worry about creating a model that other people have to replicate. You can just go, “You know what, I’m gonna change the design for this pose, ‘cause that expression reads better.”

That’s hard to manage on a television production where you’ve got hundreds of artists working on it. But, when I’m doing a comic where the print version is the only thing, then I have a little more freedom to change the design slightly if I need to.

Speaking of that — what’s sort of drawn you to keep going back to animation over the years?

I like filmmaking, a lot. Like I said, I always wanted to be a print cartoonist. But then, when I was in high school and I started coming up with ideas, I was realizing, “Oh, I have an idea for some really funny music for here.” Or, “I want the character to move in a funny way.” Or, “I have this specific way I want the character to say this line.” And it was impossible for me to get some of that humor on a comics page.

I started analyzing where my brain was, and going, “I think I may be happier, and able to express myself truer to what I want to do, if I kind of focus my attention towards film. Because I like sketch comedy, and I like animated cartoons.” And I’m realizing, a lot of my ideas wouldn’t reach their full potential on a printed page.

Right.

I noticed that there’s a cartoonist named Rob Schrab — he’s now a director. He did this comic called Scud. And he would put little asterisks and go, like, “Listen to this music when you’re reading this page!” So, he too was thinking as a filmmaker. He ultimately became a filmmaker and directed a lot of comedies. But I read his comics and I’m like, “Oh, he’s telling me what track to put on.” And that’s sort of where my brain was, too.

Also, the comic strip industry in the early ‘90s was dying and not really a thing, but animation was booming. So, I was like, “Maybe that’s a better path.”

No, that makes sense. I guess this is a more general question, but what feeds your inspiration to keep drawing and creating?

It’s just kind of a compulsion; I just love doing it. Like, my brain works that way. I come up with an idea and I need to put it on paper. I need to draw it; I need to see it. And that goes back to when I was a little kid. Even before I could draw, I would have a picture in my head and I would ask my dad, “Hey, can you draw me Shazam hanging out with Underdog?” Just ‘cause I needed to… like, this weird compulsion to see it.

When I do come up with a new idea, I immediately have to get it down. Then, once I’ve drawn it and like it, I want to see more of it and I want it to become more realized. I think that’s a lot of what it is; just the way my visual brain works. I just want to see this stuff.

So, over the years, your shows have always changed style and approach — I mean, at least from my perspective — and always come at things from a new direction. And I’m wondering, how do you consistently keep things so fresh?

I think it’s just trying to find the thing that feels right for the idea. Different kinds of design approaches give you a different feeling or a different energy. And so, when I’m designing a show — based on the tone of the show, like, “What kind of show is it?” — then you adjust the drawing style to fit that tone.

As I was developing Wander, I’m like, “Okay, this is an unapologetically cartoony show. So, let’s make these designs really malleable and animatable.” Whereas a show like Kid Cosmic, that story is much more grounded in reality, so those designs were less like cartoon characters and more in a line with, like, Hergé or Dennis the Menace — where they felt more like real people.

A lot of it comes from, “What’s the tone of the show that I’m producing, and what design style expresses that or complements that?” Powerpuff was really graphic and really bold, and it was cute, but it was also tough. So, having the big, fat, black outline added that edge to it. Whereas, if they were really thin and delicate, they wouldn’t have seemed as powerful and strong. A lot of it is just finding a design style that reflects the tone and the idea that we’re trying to get across in the show.

Yeah, no, absolutely. When you’re thinking about these show concepts — like, drawing and working out ideas — at what point do you feel, “Okay, this would make a great show.” Where do you decide, “I should move forward with this”?

If I come up with a concept that I like, that I get excited about, and then if I come up with characters that I fall in love with. Ideas are interesting, and concepts are interesting, but if you can’t deliver on the character and personalities and… ‘cause that’s what is the most important. As soon as I find the character aspect of it and fall in love with the characters, and I want to tell their story, that’s when I kind of obsess on it.

And I have this weird theory that all story is “who, how, what and why.” And what and why is informational, and it’s interesting, but who and how is why people watch entertainment. They want to see who is doing it, and how are those people doing it — as opposed to what is happening and why did they do it. You know, I always compare the Marvel movies to DC movies, where Marvel movies are who and how, and DC movies are what and why.

And what and why is interesting, and it’s good information. But if you’re not delivering fun, entertaining, relatable, likeable characters, it kind of doesn’t matter what the idea is. So, I always try to get the characters front and center as fast as I can, as opposed to just selling the concept.

Right.

Yeah. And, also, I like concepts that are kind of simple and easy to get. Like, “Oh, I haven’t seen that before.” Or, “I’d like to try to take a crack at doing that. That might be fun.”

On that note, what was the core concept behind Kid Cosmic, your most recent series?

A lot of kid hero, superhero things… there’s this thing in the entertainment industry, especially in animation, it’s aspirational. We want to show kids the person they wanna be. And I’m like, “That’s not fun! That’s not entertaining; that’s not relatable.” I wanted to do a kid superhero show about what a real kid would be like.

So, this fantasy idea of, “Wow, if I found cosmic rings of power and I got superpowers, and I would put a team together…” In any other place, they would be the coolest team, and they would be amazing immediately. And I went, “My favorite parts of the superhero movies are watching them screw up, when they’re not good at it. What if I could do that? What if I made that show — a kid who got powers, but he just was failing the whole time?” And him being a fan of comic media and superhero movies, he’s expecting it to be like it is in all the media he’s ever watched. And, when it’s not, it drives him crazy.

I really liked that balance of fantasy versus reality. And that’s sort of what drove me to do it — ‘cause there’s lots of superhero things; I’ve done them before. But doing it that way, from the perspective of real people, and him assembling a team of the random people that happened to be around him. You know, he’s got an old man and a teenage waitress and a toddler and a cat. It’s just what was available to him at the time, you know, and he just made it work. That was really appealing to me, to try to tell that kind of story.

Yeah, I love it.

The human story, really.

So, from Powerpuff through Kid Cosmic, do you see a throughline to your shows?

Yeah, definitely, definitely. I tend to do stories about kinda underdogs, characters you wouldn’t expect to be stars of shows. Even though the Powerpuff Girls weren’t underdogs per se, the idea that they were three little girls is, people would underestimate them. They wouldn’t expect them to be heroes. And all the friends in Foster’s weren’t with their creators anymore, and they were in this house, and they were hoping to get a new friend.

And Wander is the most unlikely hero you could ever expect. I mean, he’s just this spirit of joy and love, and doesn’t have any powers and doesn’t fight anybody and stops people with positivity. And, like I said, with Kid Cosmic, they were just regular people. So, there is this theme of underdogs and people you wouldn’t expect to be the stars of these stories. I seem to just gravitate towards those kinds of things.

Right. Going through your archives — all these development drawings, and these other things you’ve done — for the Gallery Nucleus show, have you had any takeaways? Sort of putting pieces together?

No, not necessarily. You know what it is… one thing that I’ve noticed is, a lot of times when I’ll do drawings, I’ll go, “Ah, these are terrible. These are really bad.” Then I’ll look back at some of these ones that I haven’t dug up for a few years, and I’m like, “What was I thinking? These are good! Why was I beating myself up so much?”

There was a period where I was trying to do a Foster’s comic strip — I wanted to retell the pilot story in a comic strip form. And I found all these versions of me trying every kind of ink nib, every kind of pen, just to try to get the inking right. And, like, what paper I was drawing it on. And I was like, “Why’d I waste all this time obsessing on this nonsense that doesn’t make a difference?”

They all were drawn well. They all were good. Like, boy, I wasted a lot of time on this technical nonsense. But it is nice to look back on that stuff and go, “Oh, this work is good. These are good cartoons and good drawings. I do like them.” Even though, at the time, I was, like, “Oh, no. I can’t show this to anybody.”

[laughing] Yeah. So, is that the kind of work people can expect to see at the show?

What they’ll see in the show, it’s a mix of early development stuff — just my thinking through the characters — combined with production work. Like, here’s my original pencil drawings of the model sheets that became the main models. So, production work, maybe some storyboard panels, a lot of development work. And some of my attempts at doing comic strips, or just breaking away from production and animation work and doing my own sketches.

You know, ‘cause Wander Over Yonder started just as a sketchbook character. When I was working on Foster’s, I would come home and just doodle and draw in a way that wasn’t for animation. It was just for me, for fun. So, a lot of that work is in there — having fun with drawing in a different way. A bunch of that’s in there.

But the thing is, when Ben [Zhu] came to me to ask about the show,3 I went through my paper drawers and my Tupperware archives in my attic and pulled out tons of stuff. And he was like, “This is way more than we need. This is multiple shows’ worth of stuff.” So, I said, “Well, you pick what you want.”

There’s a few things where I was like, “Oh, I’d like to see that in there.” But most of it was him and his team just selecting what they thought people might want to see. There’s way more I have that isn’t in that show, so this isn’t necessarily, “Oh, this is the best of the best.” This is a sampling of what I happen to have in my archives.

That’s crazy. So, you’re somebody who still draws for yourself, outside of show development?

Oh, yeah. I try to. I keep coming up with ideas, and then I want to get them down, so I have some version of it somewhere. So, yeah, I’ve drawn a lot. I just like doing it. It’s meditative; it’s relaxing. I’ve found that, if I don’t draw for a period of time, I tend to get depressed and just get frustrated. Then I’m like, “What’s the matter with me?” And I realize, “Oh, I haven’t drawn for three weeks.”

It’s not even doing finished drawings — it’s just doodling something, or drawing something on a Post-it. Just going through that process is healthy for me and helps keep me sane.

And it’s interesting that there’s not tons from Kid, at least original art from Kid, because all that was drawn digitally. All that’s drawn in Sketchbook or Photoshop or Procreate. So, I’ve got tons of art, but none of it’s on paper. I told Ben, “I don’t have tons of paper, original stuff for that show, ‘cause it was all kind of digital.” But he was okay with putting some prints from the digital stuff in there.

Now, this is sort of an out-of-left-field question, because it was on my list and the conversation didn’t quite go there… what was it like when you first saw your work on TV?

Well, it was a while before I actually could do that. The first real show I worked on was 2 Stupid Dogs. Then the show that I worked on that was really a lot of my work, as far as storyboarding, was Dexter’s Laboratory.

But, when Cartoon Network first came out, it was only available on the East Coast. We didn’t get a West Coast feed. Genndy and I and the crew couldn’t watch Dexter’s [laughing].4 We would make the shows, send them to Cartoon Network and they weren’t on our cable stations, so we never got to see it.

But it was exciting. And, again, it was pre-internet, so it was hard to know what people thought of it. The only feedback we got was from Cartoon Network, and they would say, “We love the show.” And the only way we knew we were doing good was they would order more. It was years and years after doing shows that I was able to get some sort of response from viewers on what they liked. But it was exciting — it was exciting to see it.

But another thing happens, and I’ve explained this to every show creator. When I did my first short and it came back from the overseas studio, I got really depressed. Because it was, “That’s different than the thing I saw in my head,” since I didn’t get to draw every drawing. Other people were interpreting the characters, or animating things a certain way, or posing things a certain way. And this thing washes over you called the “workprint blues” — the workprint is the first film that comes back from overseas.

And I kinda had to learn over the years that it will never be, ever, what it is in my head. Because the nature of this medium is, you’re collaborating with other people. Other people have their skills and their talents, and they’re adding their creativity to it. So, you kinda have to accept, “Okay, there’s gonna be the thing that I can see in my head, and then I need to respond to, ‘What is it really like?’ ”

What does it look like when other artists have touched it, and everyone responded to it? And learning to accept what that is, and then to try to make that the best it could possibly be. Because, if you try to make it exactly like what’s in your head, you’re going to frustrate your crew. You’re gonna drive everyone insane; it’s gonna be hard to work with you.

So, I’ve just had to learn over the years, it will be different. It will be different than what you’ve been seeing in your head through the years, and that’s okay. That doesn’t mean it’s bad. You know, it’s just different. And I’ve learned over the years, different doesn’t necessarily mean bad. So, yeah, I’ve gotten more used to that. It’s going to evolve into a new thing once you collaborate with other people. You know?

Yeah. No, I love that attitude. So, let me see. Right now you’re working on Powerpuff?

Well, I’m currently developing for Warner Bros. and Hanna-Barbera Studios Europe. I’m putting together a development package for a new Powerpuff project and a Foster’s preschool spin-off series. So, I probably started working on that full-time around September of last year. Did my presentation to Sam Register and the studio folks around December; they loved the direction.

And now, we’re just putting together our presentation package. Like, “What do we need to show them to sell it to a streamer, in order to get financing to produce it?” That’s what I’m currently working on — putting those presentation packages together, to see if we can get funding to make them.

Because the industry has gone through massive changes in the past few years, and nothing’s really getting greenlit. There isn’t an outlet to just make shows anymore, like there used to be, because streaming has kind of shut down the networks. And all anybody wants now is things they’ve seen before, or things that they can acquire from overseas for cheap to put them on. Like, nobody wants to invest in a new idea.

And so, for even things like Powerpuff and Foster’s, we have to put together a very slick package of, “What is this gonna be? What are the episodes like? What’s it gonna look like? Why are we investing our money into making that?” So, yeah, that’s what I’m doing right now.

Very cool. And, this is just sort of a stray question, because I’ve actually run out of questions —

[laughing]

[laughing] But, as to your point about new ideas, you’ve mentioned I think on social media having over a dozen ideas that you’d pitched around and not had picked up. And I’m wondering — just how many ideas do you have in the vault?

Right now, probably 20. And some of them aren’t fully fleshed out; they’re just elevator pitches. Like, “Hey, this blah-blah-blah-blah-blah-blah-blah,” with a couple drawings. They’re not fully formed shows, but I’ve probably got upwards of 20 or more ideas where I’m like, “Oh, that could be interesting.” And I keep coming up with them, and then I write some notes down and do some artwork.

After we finished Kid Cosmic, I was doing development for Netflix for maybe nine months or whatever. And that was my job — just come up with ideas. So, I’d be like, “Here’s some preschool shows. Here’s some 6-to-11 shows. Here’s an idea for a movie.”

And some of them were things I’d had in the past, but a lot of them were new. Netflix wasn’t looking for fully realized, “Show us the whole show with episode ideas.” They were like, “Just show us launchpads. A concept, a title, some characters. What’s the vibe? What’s the tone?” So, I did as many as I could, ‘cause I wasn’t sure what they were looking for. You know, they wouldn’t tell me what they wanted. I was just, “How about this one? Okay, you don’t want that one. How’s about this?”

It was kind of throwing everything at the wall, trying to see what would stick. And they ended up not going with any of them. They’re not really making anything right now — I mean, there’s a few things that they had greenlit years prior that they were finishing up. But a lot of projects they actually had in production, they canceled.

My wife Lauren had a show, Toil & Trouble, in production at Netflix.5 They had written all of season one. They were ready to ship the first episode to the animation studio. They were mid-writing season two. And they just pulled the plug on the show, and Lauren had to fire 50-plus people in one day. Just, like, “Yep, we’re not making that.” So, they just reached this point where they were kinda timid about greenlighting things or taking risks on new ideas. You know, it’s just unfortunate.

So, yeah, I’ve stockpiled all these ideas ‘cause, if they said no to it, I get them back. They don’t own them, so I’ve got them all. And I’m just kind of holding on to them till the industry cycles back around and people are looking for new stuff. Then Warner Bros. came to me and said, “Hey, there’s interest in Powerpuff and Foster’s.” And I’m like, “I like these new approaches to those shows, and I’d be happy to try that.”

Yeah, absolutely. So, I guess to just wrap things up — for people who are going to the show who maybe are not in the industry yet, or want to be in the industry, is there sort of a lesson they could take away from the show, or something it could show them?

I think maybe one thing they’ll get from looking at the bulk of it is that making these projects is this constant process of exploring and trying ideas. You’ll see a lot of, like, “Oh, Wander looked totally different for a while and was drawn in a different style, then it cycled back to this other style.” And you’ll see some designs of the characters that were in Kid Cosmic for a while that didn’t make the cut.

And so, the idea is, you’ll see that you don’t have to be so precious about getting it perfect in the beginning. You go through the process of developing and figuring it out, and sometimes you may head down a wrong path and develop something in a way that you’re like, “Eh, I don’t like that.” You can always cycle back and find the right version of it, and still end up making a good project.

It doesn’t have to be so perfectly executed from the minute you start. You know, allow yourself to explore a little bit with your drawing style, or the concept, or the behavior of the characters. And that’s the only way you’re gonna figure it out, is by doing it. You can’t just sit down and go, “I have an idea for a show. I’m going to try to conceive of the whole thing and then execute.” It really is this constant, daily process.

Because people have asked me in the past, “Did you know every episode of Powerpuff Girls before you made it? Did you have the plan?” I’m like, “No!” Most of these, you go week by week. Like, “All right, we know the concept, we know the characters; now let’s just start making them.” There’s no master plan. It really is just spontaneously exploring the characters of the show and trying to arrive at good stuff.

And so you’ll see that, I think, on the wall. You’ll see that creative exploration.

Our special thanks to Craig McCracken for talking to us. We’re excited to see how his next two projects develop. Meanwhile, if you’d like to see more about his exhibition, you’ll find the details on the Gallery Nucleus website.

Until next time!

Jules Engel was one of the core artists at UPA, responsible for much of the color design and painting across the studio’s films.

McCracken told us something similar last year, replying to our article on the creation of the Powerpuff Girls’ designs. “The other thing that helped their design evolve was repeated drawing over and over,” he wrote. “Over time a shorthand develops where you eliminate the unnecessary and only draw what is essential.”

Ben Zhu is the founder and owner of Gallery Nucleus.

Genndy Tartakovsky created Dexter’s Laboratory. McCracken was a main crewmember on the series — working as a storyboarder, director, art director and more.

Lauren Faust (My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic) has shared some of her and her team’s artwork for Toil & Trouble on Twitter. She retains the rights to the series and has written that she hopes to revisit it one day.

I loved the Powerpuff Girls and Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends! It's so intersting to see how he designs characters and prefers to keep his design simple and clear.

Another great post. The development pieces never cease to amaze me how much effort and creativity goes into each piece. A true genius 😁