Welcome! We’re back with another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our agenda for the week:

One — Samurai Jack and The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon.

Two — the week’s animation news around the world.

Three — the retro ad of the week.

Four — the last word.

If you’re new to our newsletter, why not sign up? It’s free and takes zero effort. Read new issues right in your inbox, every Sunday:

With that out of the way, let’s go!

1. The film that made Samurai Jack

American animators have taken inspiration from Japanese anime for decades. All the way back in the ‘80s, Disney was already borrowing from Hayao Miyazaki for the clock-tower battle in The Great Mouse Detective. The influence of anime only grew more pronounced from there.

Take Samurai Jack. Created by Genndy Tartakovsky of Dexter’s Lab fame, the series is one long homage to anime like Akira. Its main reference point wasn’t quite so obvious, though. Surprisingly, at the center of Samurai Jack, you find a retro classic from Toei Doga. It’s the 1963 film The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon.

According to Chris Battle, an artist on Samurai Jack, it all started during The Powerpuff Girls. In the late ‘90s, staffer Chris Mitchell played the crew his Japanese LaserDisc copy of The Little Prince. The film made a huge impression on Tartakovsky.

“I'd been doing black lines all through Dexter, all through Powerpuff, and I was just kind of sick of it,” he told Allan Neuwirth in Makin’ Toons. The Little Prince was a revelation. Tartakovsky explained that “there were some self-colored lines, but because the print was old, it appeared that it had no lines around it. And it had a great feel to it.”

And so he began to collaborate with Dan Krall, another Powerpuff crewmember, to craft Samurai Jack. Along the way, the show would draw from 1950s aesthetics, Miyazaki, kung fu movies and more. It would become one of the best-loved cartoons of the 2000s.

But what about The Little Prince? While it’s obscure in America, it was an animation landmark even before Samurai Jack borrowed from it. An all-star crew put it together, drawing just as deeply from global animation as Tartakovsky did. What they built became a defining achievement in early anime.

The path to The Little Prince was a winding one, though. Toei started as a live-action studio. Then, in the mid-1950s, it bought an animation company, renamed it Toei Doga and poured money into anime. As animator Makoto Nagasawa later recalled, the hype was that Toei would become the Japanese Disney.1

That promise drew as many as 800 people in the first call for applicants. The few who made the cut, like Nagasawa, were art-school students, manga artists and more. These new hires weren’t trained animators yet — they brought fresh eyes and perspectives to animation. Mentored by Yasuji Mori, a holdover from before Toei’s buyout, the team made ambitious films like Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958).

But Toei was no paradise. Animators made around 5,000 yen per month at first, according to ex-staffer Taku Sugiyama. That’s roughly $450 in today’s money. On a project in the early ‘60s, the crew reportedly worked “more than ninety hours a month of unpaid overtime.” They formed a labor union and took up a bitter fight with management. Some disgruntled staff left for Mushi Production, run by Osamu Tezuka.

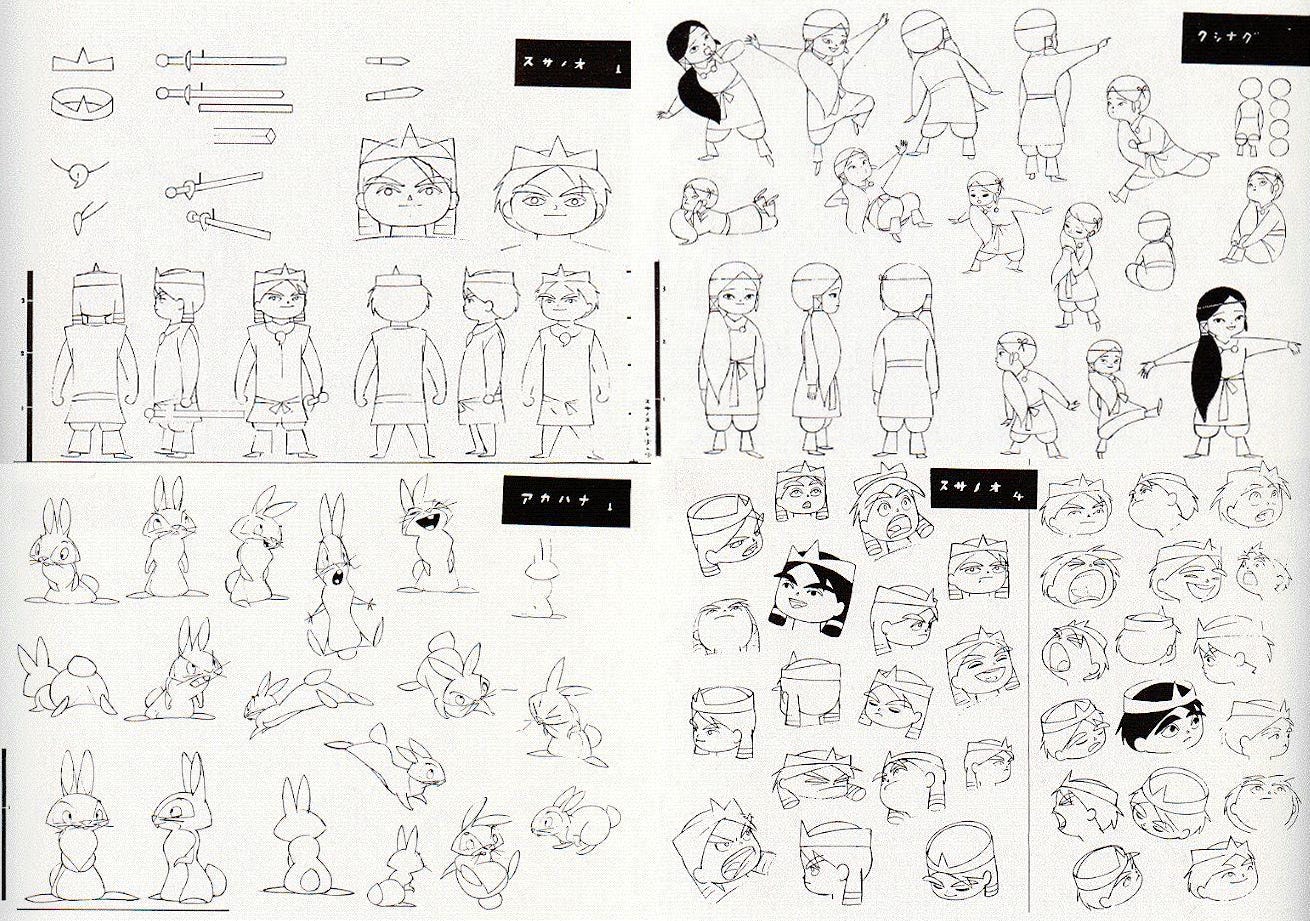

The Little Prince was created in this environment of chaos and genius. Based on Japanese mythology and scored by the composer of Godzilla, the film is a sweeping epic that plays out like a series of vignettes. At the core is Susanoo, a swordsman-god who travels the world and, in one dazzling setpiece after another, frees locals from the tyranny of monstrous fish, fire gods and the eight-headed dragon itself.

Directing the film was Yûgo Serikawa. In his own telling, though, The Little Prince was a team effort powered by meetings with the top staff. A crucial member of those meetings was Isao Takahata — an assistant director here, and later a cornerstone at Ghibli. Another was Yasuji Mori, whose design and animation style rings throughout the film.

Mori was looking at animation way outside the Disney norm for The Little Prince. Per Nagasawa, UPA’s flat, graphic style was a major influence — alongside European animation like The King and the Mockingbird and the Soviet Snow Queen. Nagasawa himself borrowed UPA’s “limited animation” trick to create snappier motion in the film’s famous dance sequence, seen below:

As abstract as the dance looks, the animators based it and many other moments on live-action video reference. Serikawa recalled filming 40 shots of a ballet company on a blistering summer day. (Takahata, a stranger to live-action shoots, couldn’t even figure out the clapperboard.)

That wasn’t the most extreme shoot, either. For the shapeshifting Fire God who later inspired Aku, Serikawa filmed actual fire. The team spent time igniting gasoline, oil and rags for the camera at Toei’s studio. Eventually, the fireballs and explosions got the fire department’s attention.

This insane level of passion and dedication suffused the whole project. Decades later, Nagasawa still remembered the atmosphere at Toei during The Little Prince. Thanks to the labor union, the team had just started to communicate freely, to read and to “think about things” for the first time, he said. Suddenly, they were “no longer passive with respect to the company and the work.”

Serikawa had a deeply personal stake in the film, too. Near the start of production, his first son, Yutaro, was stillborn. He told Yasuji Mori that he wanted The Little Prince to be good for his son’s sake. (Mori was an emotional pillar at Toei and helped Serikawa work through the tragedy.) After that, Serikawa wrote that he couldn’t separate Susanoo from his son — they looked the same to him. He was part of the film.

Despite their relative lack of experience, and despite Toei’s broken management, this group of people imbued The Little Prince with an intense love. Watching it today, it still lights up your imagination. It’s a whole world. A world that spoke to Tartakovsky, but not just to him. It also spoke to Tomm Moore of Cartoon Saloon — and to the team at Nintendo, who tried to capture it in The Wind Waker.

Even now, The Little Prince is still speaking.

In a few days, it’s the 20-year anniversary of Samurai Jack. That show still has a spark inside it that feels immortal — like no time has passed since it premiered. As you look back on the show, don’t forget to look at its biggest influence, too. That spark inside Samurai Jack is an ember of The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon, a film that never burns out.

2. News around the world

Comings and sad goings in Canada

It was a busy week in Canadian animation. That wasn’t entirely a good thing. On Tuesday, news broke that Tangent Animation of Winnipeg and Toronto would close. According to Cartoon Brew, up to 400 employees will be losing their jobs.

Tangent just wrapped Netflix’s Maya and the Three, the long-awaited series from Jorge Gutierrez. It had two other Netflix projects in the works — High in the Clouds and The Monkey King. The latter was a co-production with Pearl Studio (formerly Oriental DreamWorks) in Shanghai. BlenderNation reports that Tangent lost both projects “in the space of two weeks, leading to its untimely and devastating shuttering.”

On Twitter, Gutierrez called the news “heartbreaking” and wrote that he was “jealous of future directors that will be lucky to create with them.”

Meanwhile, Disney revealed on Wednesday that it would open a Vancouver branch of Walt Disney Animation Studios. Its focus will be series and specials for Disney+ — starting with a Moana series in 2024. The studio is already recruiting. As an aside, it’s worth noting that animation unions remain weak in Canada. Less than a year ago, Titmouse Vancouver became the first studio in Canada to join the Animation Guild.

BUSINESS: Anime production industry shrank in 2020

On Monday, Teikoku Databank published a grim report about how Japan’s anime industry fared in 2020. As expected, the impact of COVID-19 hurt production companies. TDB’s data shows that the industry shrank in 2020, ending a decade-long growth trend. But it’s a mistake to chalk it all up to the pandemic. As TDB writes, the problems run deeper. The anime production business may be stagnating.

By TDB’s numbers, the industry shrank by 1.8% in 2020. That’s worse than it sounds. The dip came despite the record-breaking success of films like Demon Slayer the Movie, and the explosive popularity of anime beyond Japan. Unsurprisingly, smaller producers were hit harder. While many major firms grew in 2020, thanks to the power of licensing fees, the subcontractors who do the grunt work of animation suffered.

A record number of subcontractor studios, over 42%, reported a deficit last year. These companies were more vulnerable to the pandemic — most rely on steady work to survive, rather than royalties or licensing fees. The structure of the anime industry siphons the real money out of most animators’ hands. Compounding these problems was a third straight year of decline in the number of productions.

Data we’ve seen elsewhere suggests that anime as a whole, beyond the industry numbers that TDB parsed, most likely grew in 2020. TDB looked at production houses — and only a few big ones got a slice of what anime earned. The lion’s share went to investors and distributors.

Finally, TDB notes that things could get worse in the near future. In 2020, the conditions of Japan’s animation workforce only declined. (As Anime News Network noted this week, 90% of Japanese animators quit their jobs within three years.) But Chinese animators are doing better, and there’s an uptick in the cross-pollination between Japanese and Chinese anime houses.

If Chinese anime continues to emerge as a strong rival to Japan, TDB warns that it could pop Japan’s “animation bubble.” Something similar happened in 2007, thanks to a dip in DVD sales. With so many companies operating in the red already, that kind of drop could be catastrophic.

Best of the rest

This week saw several major deaths in animation. One was Thea White (81), voice of Muriel in the American series Courage the Cowardly Dog. Another was György Matolcsy (91), founder and former head of Hungary’s Pannonia Film Studio.

Vivo by Sony Pictures Animation, an American production, hit Netflix on Friday.

Starting next month, the Academy Museum in America will sell a 288-page catalog of art from Hayao Miyazaki’s films — including production material that’s “never been seen outside of Studio Ghibli's archives.”

The American streamer Crunchyroll announced its next batch of original series. On the list is the long-delayed High Guardian Spice, which wrapped back in 2019.

In Japan, the venerable Hiroshima International Animation Festival closed up shop last year. Now there’s Hiroshima Animation Season, and indie legend Kōji Yamamura is helping to direct it.

Polygon Pictures in Japan, known for its CG animation on projects like Tron: Uprising and Star Wars Resistance, is opening a branch in India. The studio says it’s trying to make up for a lack of rigging artists.

Meanwhile, Disney India has picked up two local productions — Bhaiyyaji Balwan and Twinkle Sharma #0007.

The Tales of Wonder Keepers seems to be a hit on China’s iQIYI streaming service. The series is a Chinese-Russian co-production by iQIYI and Wizart, based in Voronezh.

Finally, the Fredrikstad Animation Festival in Norway has revealed this year’s selections in the Nordic-Baltic category. The festival starts on October 21.

3. Retro ad of the week

We tend to look at the 1950s as a naive, aw-shucks era. The reality was more complex — as the ads of the day show. Even back then, the modern form of advertising was old. People were skeptical of its tricks. When TV boomed during the ‘50s, it developed new strategies to reach this more jaded audience. Ads began to parody advertising, and to pitch products ironically.

“The ironic ad,” as Paul Rutherford wrote in The Art of Television Advertising, “positioned the viewer as a knowing consumer, an experienced veteran who was familiar with the ways of hype.”

John Hubley helped to pioneer this style of TV commercial at his studio Storyboard. See Instant Money, for example. It comes from their hit series for Bank of America — a campaign that scored “notable sales success” and the acclaim of the ad industry, per Billboard. With Instant Money, we find one of the most celebrated ads in the bunch.

This is a quick, 20-second spot based on an idea by Hubley and his associate Bob Guidi, according to the Cartoon Modern blog. Advertising historian Lincoln Diamant described Instant Money this way:

In the era before “creative types” in advertising agencies had learned enough to start telling their suppliers how to do it all, Storyboard Productions, always innovative with animation, was powerfully innovative with content. Here John Hubley is again among the earliest to spoof commercials. TV’s instant-pick-me-up of a cup of steaming coffee is transformed, through the undisputed magic of animation, into the happiness of a bank loan.

The crew does a lot with only 20 seconds. Rod Scribner, famous for his work at Warner, animates the spot in his zany, spastic style. Instant Money looks expensive — and it probably was. Storyboard was known to take three months to deliver a single one-minute, black-and-white commercial, and each one cost clients the equivalent of over $100,000. See the whole thing below:

4. Last word

Thanks for reading! We hope you liked this week’s edition. Catch us next Sunday for more animation highlights from all around the world.

One last thing. We were really pleased with the response to last week’s feature story about Miyazaki and The Snow Queen. Thanks to everyone who enjoyed it, whether you shared it or saved it for yourself! A high point for us came when 2×2, the long-running Russian TV channel, published an article about our piece on its website. Editor Natalia Lobacheva has our gratitude for covering it.

Hope to see you again soon!

This detail comes from a long, Japanese-language interview with Makoto Nagasawa, published by the site Anime Style in 2004. We reference this interview throughout the article. Another key source is this essay by Yûgo Serikawa. For both links, we have to thank the animation historian Toadette, author of the ultra-informative blog On the Ones.

Currently rewatching Samurai Jack and this was such a great thing to read. I can't wait to check The Little Prince out!

Thanks for this piece.