Happy Sunday! We’re back with a new issue of Animation Obsessive. Our main story today covers a Soviet feature film we’ve wanted to highlight for more than a year. It’s thrilling to share it at last.

On that note, our lineup:

1️⃣ Detailing The Bath (1962), with rare information and new subtitles.

2️⃣ Animation news from around the world.

If you haven’t already, it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. They’ll arrive right in your inbox, every week:

With that, we’re off!

1: “Enormous explosive power”

In the Soviet Union, animators and the government locked horns. It was inevitable. State bodies funded most animation across the history of the USSR — and controlled most studios. They were your bosses, your distributors and your censors. Bureaucracy both supported your work and caused your problems.

As the late, great animator Fyodor Khitruk (Winnie-the-Pooh) once said:

We had to fight against the officials. And this was only possible together. I’m afraid that the [animation] community was based on opposing a common enemy. We, by the way, were fed by this enemy. But we knew what we were fighting for and against.

Their grandest rebellion took place in the ‘60s. Back then, the Khrushchev Thaw was opening up the USSR and rolling back Stalin-era rules. For political reasons, animators had long been obliged to draw realistically, in a Disney-inspired style. Films critical of the state had been off the table. Now, those restrictions were loosening.

Animators took their chance. They threw away realism and experimented wildly. Some made films that questioned, openly, the very officials who paid their salaries.

In the excitement of the time, a few such political films got greenlit, funded and distributed. One is Khitruk’s Man in the Frame (1966), which we’ve covered before. But an even earlier film — one so bold that it’s hard to believe — is The Bath (1962).

The Bath shocked us when we first ran into it online. It’s an experimental feature whose artistic ambitions rival anything in animation at the time — and not just in the USSR. It’s also the harshest satire of Soviet bureaucracy we’ve seen animated. It’s a firebomb lobbed at its own bosses. It’s pure audacity, and we love that about it.

Yet it’s obscure. The Bath has had English subtitles for years, but we found them hard to parse and struggled to learn more about the film. So, we spent part of our vacation studying and translating it. We’ve produced a new English version, based on several older ones (see the notes1), which we feel makes The Bath more accessible than it’s ever been.

Today’s issue is dedicated to introducing The Bath — and to telling its story. You’ll find the film in English below. For more on what makes it so unique, read on.

To understand The Bath (or Banya), you first have to know the name Vladimir Mayakovsky. He was a poet and playwright in the early USSR — and so famous that his funeral in the 1930s was “the largest demonstration of public mourning since the funeral of Lenin himself,” according to historians.

Mayakovsky was a brilliant, loud, relentless provocateur. He was an avant-garde artist, a staunch Leninist and a man of the people. He hated bureaucracy and tried to destroy it with his famous play The Bath (1930), subtitled “A Drama in Six Acts with a Circus and Fireworks.” The bureaucracy hated Mayakovsky back — his enemies despised him as fiercely as his fans loved him.

The people who adapted The Bath into animated form, working at Soyuzmultfilm in Moscow, counted themselves among his fans. The film’s co-director, Anatoly Karanovich, wrote that Mayakovksy’s name:

… was not only the name of our favorite poet. It was like it served as a watershed, with your friends on one side and your enemies on the other. It is inextricably linked to the youth of my generation, who entered into independent life in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s.2

The animated Bath is a love letter to Mayakovsky. It’s based on the play, but also on his other work. Snippets of his essays and personal notes turn up as dialogue. Posters he made in the ‘20s appear in the background. Co-director Sergei Yutkevich noted that a few moments from Mayakovsky’s play The Bedbug (1929) even show up toward the start, in a market sequence that “introduce[s] the viewer into that amazing, now historical, atmosphere” of the post-revolution.3

But the point of animating The Bath wasn’t to pay tribute to the past. It was to announce the return of Mayakovsky’s destructive spirit to animation — and the end of the repressed era of Soviet art.

Both directors felt it was necessary to “strike at today’s bureaucrats who are hindering the forward movement of our country,” as Karanovich put it. To strike at the USSR’s powerful philistines, its social climbers, its careerists and bootlickers. The Bath was the perfect story to do it, as long as it was adapted to the new era. In fact, Karanovich felt there was no other way to stay true to the original:

We wanted to make it today, without any hint of backward-looking restoration. We wanted to be loyal to Mayakovsky. What does that mean? Some people think it means following every letter of the author’s text, slavishly copying, executing all of the author’s notes literally.

We thought otherwise.

Loyalty to the work of Mayakovksy means preserving its ever-living, furious and offensive spirit, the indispensable search for the new, the bold destruction of obsolete canons.

Not long before August 1960, when The Bath began at Soyuzmultfilm, these ideas would’ve been unthinkable. Karanovich wrote that Mayakovsky hadn’t been animated since the anti-racist cartoon Black and White (1932). Now, these ideas were very thinkable — The Bath was among Soyuzmultfilm’s several new Mayakovsky projects.

Karanovich and Yutkevich would spearhead a film with an “experimental character unprecedented for the cinema of that time,” according to writer Oleg Kovalov. A political and artistic assault on Stalin-era aesthetics, and on the bureaucrats of the old order.

The Bath is a story about an inventor, Strangefellow, and the time machine he’s trying to build. It really does work — yet he finds his project caught in the endless red tape, dead ends and labyrinths of Soviet bureaucracy. Ultimately, a time traveler, the nameless Phosphorescent Woman, arrives from 2030 to carry the worthy into the coming “Age of Communism.” The question is: who’s worthy?

Like the play, the film is a comedy that doubles as a piece of agitprop. It’s open propaganda for communism, complete with an inspiring march, but also an open critique of the people managing communism. A lot of screentime goes to the antics of the ruling class, like the pompous airhead Conquerbonce and his unbearable secretary Blockway. There are great jokes, whether or not you know the original context.

These villains are caricatures, as they are in the play. Mayakovsky wrote that they’re not “live people” but rather “animated tendencies” — trends in motion. It was this turn of phrase, animated tendencies (ozhivlennye tendentsii), that Karanovich cited to defend making The Bath with stop-motion puppets, rather than live actors.

Which isn’t to say that live actors are absent from the film. Comedian Arkady Raikin walks on screen in one of the best scenes. The puppet bureaucrats stop the story and demand to see a preview of the very film they’re in — and to interrogate the human “director” about its meaning. It feels like a meeting with Goskino, the film approval and censorship board, caught on camera.4

The team didn’t stop at mixing humans and puppets. The Bath sometimes gets called “film collage” — it’s a jumble of 2D animation, paper cutouts, lace, stop-motion and live puppetry, candy wrappers, old photos, real actors, documentary footage and more.

This visual component is the film’s greatest addition. The inspiration for it was (again) Mayakovsky. Karanovich and Yutkevich, who wrote the film as well as directed it, both pointed to the play’s subtitle — a drama with a circus and fireworks. It’s a “paradoxical combination of seemingly incompatible concepts,” Karanovich wrote. And so their film would be.

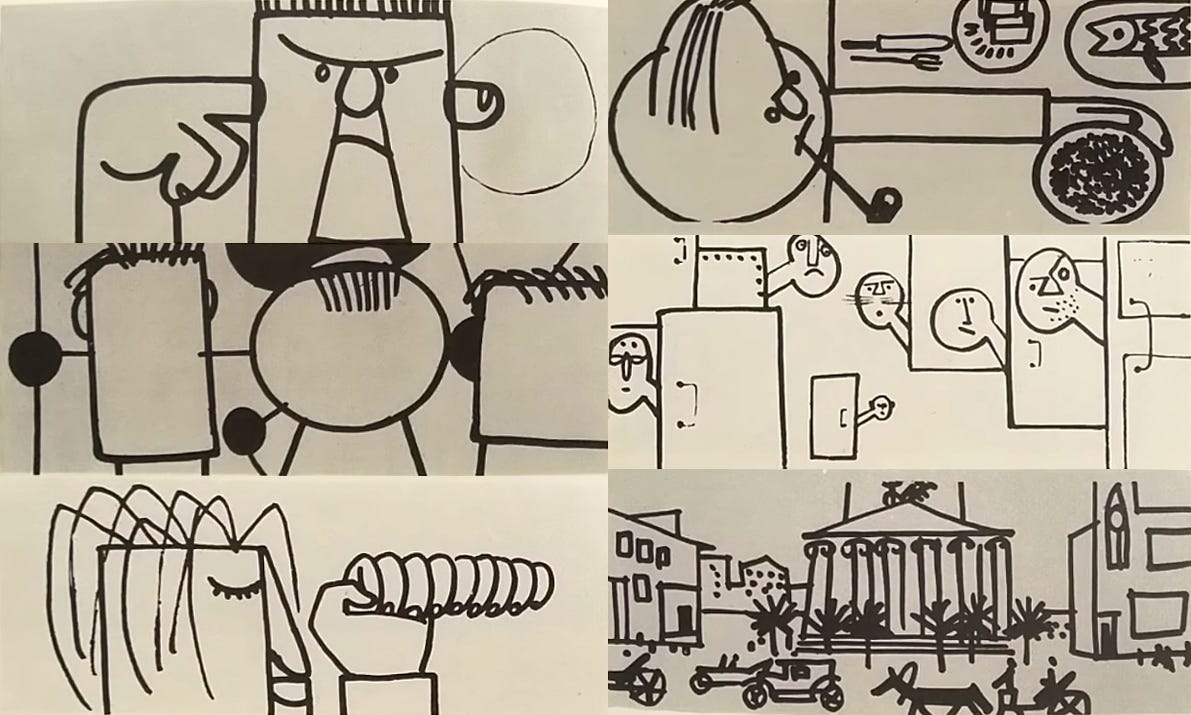

The chief architect of the look was Felix-Lev Zbarsky, soon to be an important new-school artist. His storyboards and character designs are full of flavor.

Part of what makes the look so intriguing is that it’s moving Constructivism — the aesthetic style that Mayakovsky and his collaborators famously used. Mayakovsky’s own drawings were, Karanovich wrote, a reference for the main character designs. Another intriguing part comes from the fact that it’s a ‘60s production. Elements of mid-century modern design sneak in, as do UPA- and Zagreb-style visual gags.

The painter’s extend-o hand, with ten or eleven fingers, is a great joke that appears even on the poster. But we saw it first in Zagreb’s Cow on the Moon (1959).

Adapting Mayakovsky to the screen proved to be “infinitely difficult,” according to Karanovich. The Bath is a wordy play, and almost all of the film’s script is a hyper-condensed version of the original. Yutkevich called dialogue the biggest challenge of the production, writing that they “parted with pain” with reams of Mayakovsky’s writing.

Karanovich felt differently:

The hardest part of our work was finding the graphic characteristics of the characters, so that they would have plastic solutions identical to Mayakovsky’s verbal metaphors.

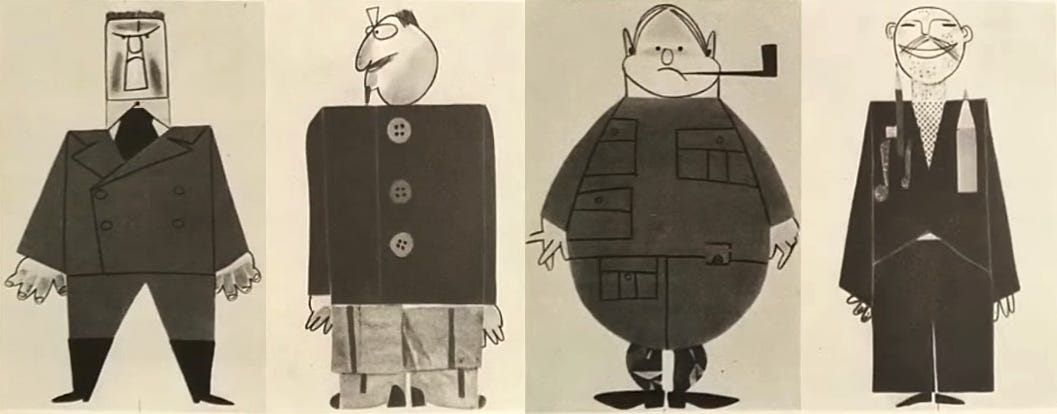

They wanted the puppets to physically embody the traits Mayakovsky had given them in writing. This resulted in designs unlike any at the time.

Yutkevich called Conquerbonce the image of “inertness, immobility and stiffness” — he was made to resemble a table or cabinet. Where his heart should be, Karanovich wrote, we find a sliding drawer containing people’s personal files. His head is visibly empty, with a hole straight through the ears. The team made literal the Russian saying dyryavaya golova: “holey head.”

Blockway’s head, by contrast, is like a polished billiard. This came straight from Mayakovsky’s text: “He’s as smooth and polished as a ball bearing. His shiny surface reflects nothing but his boss — and upside down, at that.” For the spy-like British character Pont Kitsch, who speaks a complex nonsense language, they went with an extendable nose for sniffing out secrets.

The biggest headache came with the design of the Phosphorescent Woman. Nothing seemed to work — they even created a version in blown glass without success. She almost derailed the film.

Zbarsky’s solutions weren’t enough this time. In the end, Yutkevich came up with something new: a flat, 2D character based on Picasso’s drawing of a woman’s face beside a dove. She became a person ascended, beyond understandable physical forms.

Which brings us back to the problem of dialogue. “It is impossible to talk to such a Phosphoric Woman,” argued historian and critic Sergei Asenin. “No wonder the authors of the script had to remove almost all the dialogues of the 2030 delegate with the other cartoon characters.”

She was one of the lucky ones — “it turned out that some of our dolls simply refused to speak,” Yutkevich explained. Their designs didn’t work at all with the dialogue. One major villain, the journalist Dashitoff, had every one of his spoken lines cut. He became a pantomime character who “could not utter a single word.”

In general, the team struggled mightily to match the script, and voices, to the images. After burning through a number of top actors, they resorted to having Arkady Raikin and his daughter Ekaterina Raikina voice the entire cast, in a style somewhere between narration and voice acting. It usually works (Raikin’s Conquerbonce is hilarious), but not always. The style wobbles, and it can become unclear who’s talking.

Karanovich and Yutkevich both had regrets about the voices. The latter said that they’d once disparaged the solution used by Jiří Trnka for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1959), where he turned Shakespeare’s words into narration over pantomime. It was exactly this kind of solution, Yutkevich later realized, that The Bath needed most.

Which is all to say that The Bath isn’t a perfect film, as its team readily admitted. Yet it’s still a huge, exciting, surprising spectacle, and it made a big splash when it arrived in mid-1962.

In the press, there were pointed debates between its supporters and detractors. One critic in Literaturnaya Gazeta dubbed it “merely an attempt to modernize Mayakovsky,” losing the spirit of the play. Yet the rebellious poet Nâzım Hikmet attacked that review, and showered the film with praise in his own.

“Yutkevich and his comrades in art have created a magnificent work,” he wrote. “They did not try to illustrate The Bath [...] And here lies one of the main reasons for their success.”

In June 1962, the back-and-forth continued at a public meeting of Soviet filmmakers and critics in Leningrad. Notable praise came from the live-action director Iosif Kheifits. “I asked Sergei [Yutkevich] how many shots were in the picture,” he said. “I was interested in this question, as you understand, not from the point of view of production, but because I wanted to say that in this picture there are not simply 540 shots, but 540 torpedoes of enormous explosive power.”

The film continued to turn heads from there. As the film historian Dmitry Moldavsky wrote:

The Bath was controversial not only in our country. It was screened in most countries of the socialist camp, where it was perceived as a new word in cinema and, more importantly, as evidence of the progressive movement of art in our society. In Sofia, in the Union of Film Workers of Bulgaria, the discussion of The Bath turned into a question — and this was quite natural — about innovation in Soviet art.

It even made its way to France, where it was praised strongly by critic Georges Sadoul — who’d named the “Zagreb School of Animation” just a few years before.

This all makes it easy to forget that Soviet animation as openly defiant as The Bath, like the Khrushchev Thaw itself, would not live long. Just a few years later, when Khitruk did The Man in the Frame, the state was unamused and barely distributed it. In 1968, animator Andrei Khrzhanovsky went down in history for Glass Harmonica, one of the rare Soviet animated films to be banned outright. He served two years of forced military duty as punishment.

The Bath couldn’t have been made in 1968, or in 1958. It climbed through a tiny window in the moment when it could. In many ways, it’s an anomaly. But it’s an anomaly that’s very much deserving of another look, more than half a century later.

2: Newsbits

If you’re a student or worker in animation, the Oscar-shortlisted animated shorts this year are free to stream until the 24th.

Here’s one we meant to report on last Sunday. Don’t miss the impressive teaser for Esther, an upcoming Argentine series that feels a bit like Akira-meets-vewn. It’s thrilling stuff that Catsuka’s already gone viral with on Twitter.

In Mexico, the studio Taller del Chucho (known for its work on Pinocchio) has a new stop-motion film in the works: Dolores, a story that ties into the ancient shaft tombs of Jalisco.

In China, the final trailer dropped for Deep Sea, a graphically lush film by the director of Monkey King: Hero Is Back (2015). This new one opened on the 22nd.

American animator Maddie Brewer will premiere her film BurgerWorld at Sundance today. It’s produced by A Studio Digital — also behind Jonni Phillips’ mind-melting Edgar’s Butterquiet Tulpa, among many others.

Shanghai Animation Film Studio’s series Yao - Chinese Folktales continues to do great in China. It debuted a new paper cutout episode this week. Meanwhile, a debate rages about whether the series is appropriate for kids.

The African Dream published a cool story about Ghana’s Ananse Show — an in-person event that’s part stage show, part puppet show, part animation.

One more from China: animator Liu Yufei spoke with the Qianjiang Evening News about his personal film How I Grew Up, a technical showcase. It’s embedded in the article with English subtitles.

In Japan, Hayao Miyazaki’s music video On Your Mark will screen in select Tokyo theaters beside Whisper of the Heart, just as it did when it first premiered. Natalie reports that it’s the first time in 28 years that the films have played together.

Lastly, we wrote about the iconic stop-motion film The Pied Piper (1986) by Jiří Barta, with quite a bit of information you’ve never seen in English before.

Until next time!

Our subtitles come primarily from five sources: two translations of the play (one by Kathleen Cook-Horujy in 1987, the other by Guy Daniels in 1968), two previous English subtitle jobs (one uploaded by TignoBaiser in 2019, the other by Eus and Chapaev in 2014) and Julie A. Cassiday’s work in Flash Floods, Bedbugs and Saunas (1998). Almost all of the character and place names are from Cook-Horujy’s version.

From Karanovich’s book Мои друзья куклы (My Puppet Friends, 1971). This is one of our main sources for the story, referenced throughout.

From Yutkevich’s section in the book Проблемы синтеза в художественной культуре (Problems of Synthesis in Artistic Culture, 1985). See also his essay about The Bath in this 1964 periodical.

A fact not lost on the Soviets. In his book With Mayakovsky in the Theater and Cinema (1975), writer Dmitry Moldavsky noted that the scene “reflects today’s debates about innovative art, its role in life and the taste of the philistine.” We use this book as a source several times.

A fantastic article and translation job! I had never actually watched this film before despite several recommendations, but your article changed that and it was every bit what you said it would be.

By the way, I've taken the liberty of editing your subtitles a bit to break up some extra-long lines and correct a few translation mistakes I found (such as the very opening poem, which was actually more correct in the 2016 subs. I tried to translate it a bit more poetically, but I'm not sure I'm quite satisfied with the result). Hope I didn't screw anything up in the process! The new version is over here: https://www.animatsiya.net/film.php?filmid=1173 (I also fixed up the Russian subs while I was at it)

Also, not sure if you mentioned it before, but the two directors teamed up once again in 1975 to direct another feature avant-garde animated-live action hybrid Mayakovsky adaptation:

https://www.animatsiya.net/film.php?filmid=449

But although it also has quite interesting segments (especially Vladimir Tarasov's segment at the 1-hour mark, and the perhaps-too-bizarre "Bazaar" segment at 19:42 animated by Ideya Garanina), the 1962 film seems to be clearly stronger.

My great-grandfather had a flower shop called Eilers on the Nevsky Prospect in Saint Petersburg, and Mayakovsky lived in the apartment upstairs. He writes about it in his book entitled The Egyptian Stamp. My father, who was born in 1912, was first arrested in 1931 and sent to the gulag and internal exile for the next ten years. But last I heard, the old Eilers shop is still a florist shop.