Shakespeare and the Puppet Master

Plus: global animation news.

Welcome! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter — thanks for joining us. If you’re new here, we cover animation from all around the world. This is what we’re looking at today:

One — how a Czech master crafted the quintessential animated Shakespeare, with puppets.

Two — animation news from around the world.

Three — the last word.

Just dropping in? We publish every Thursday and Sunday, and you can sign up to receive our newsletter right in your inbox:

With that, let’s go!

1. Puppeteering Shakespeare’s dreams

It’s not easy to animate Shakespeare. Since the birth of film, well over a thousand live-action projects have adapted the Bard, but animated takes have been scarce. The plays were written for live actors on a stage — a lot can go wrong when you switch them to animation. You need a master to make it work.

A master like Jiří Trnka.

To this day, no figure in Czech animation looms quite as large as Trnka. He came from the world of Czech puppet theater, an old and precious tradition that he evolved into the film era between the ‘40s and ‘60s. From his studio in Prague, he reshaped stop-motion animation as a whole. Scholar David W. Paul once wrote that it’s “hard to exaggerate the consequences of Trnka’s work.”1

When Trnka delivered his own animated interpretation of Shakespeare in 1959, the feature film A Midsummer Night’s Dream, it was clear that no other director could have made it.

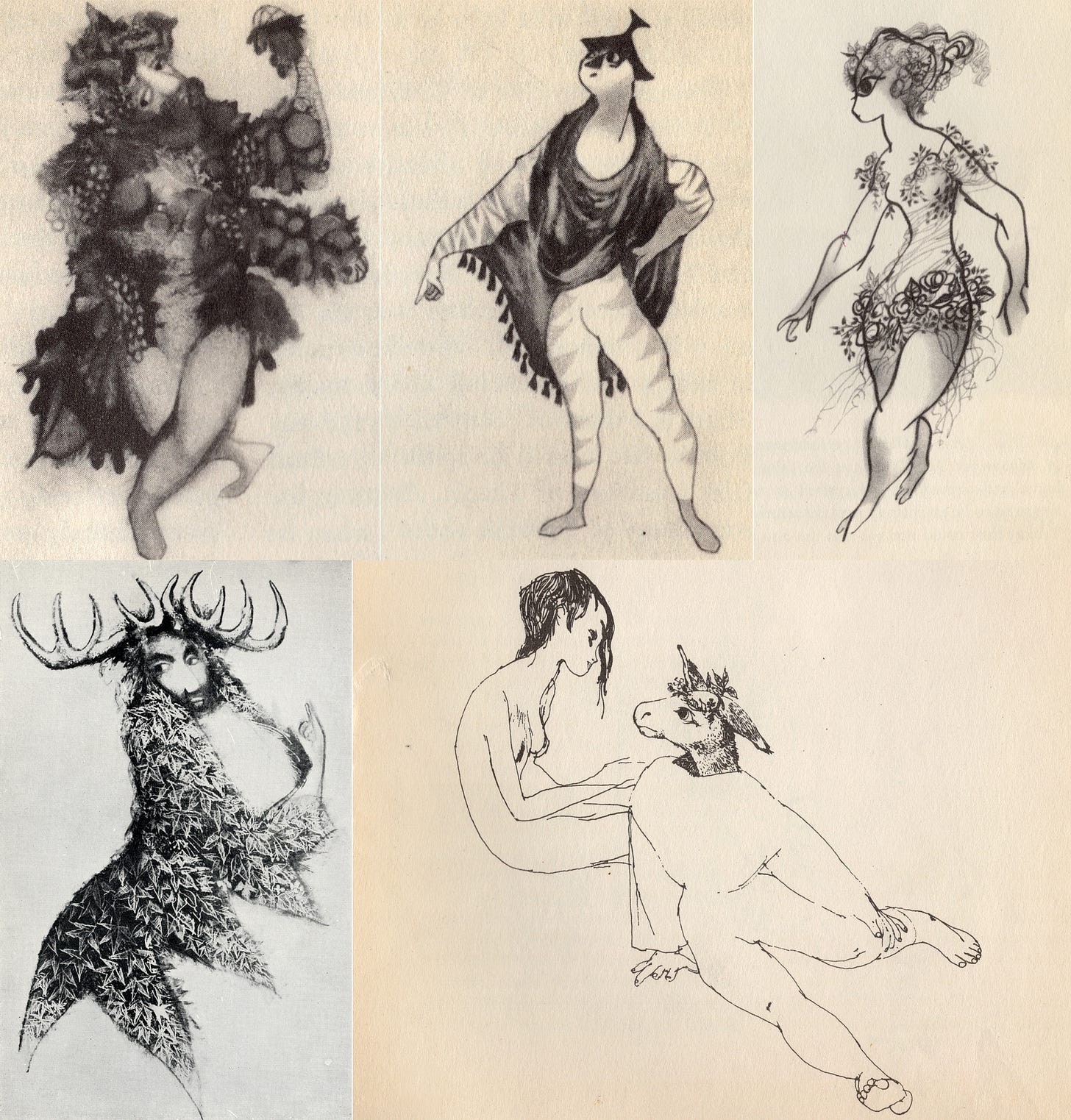

The Trnka version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is “a ballet of mime and fairies,” as he explained. It turns Shakespeare’s play into an otherworldly vision — one largely without words, save for bits of narration. Trnka’s biographer, Jaroslav Boček, wrote that the style of the film “arose naturally from the act of transposing the atmosphere of Shakespeare’s comedy into a puppet film”:

He wanted to retain all the sparkle and lightness of the original, which he felt might have been lost by words delivered by puppet actors. He felt the fragile artistry could be preserved by a puppet ballet.

By going around the trap of adapting Shakespeare literally, Trnka made the film his own, while also staying faithful to the spirit of the play. What he made envelops you in lush and often hallucinatory visuals for 75 minutes.

The sets and puppets in A Midsummer Night’s Dream are gorgeous, hyperdetailed designs — but they aren’t the only things happening here. The score is haunting throughout. The stop-motion animation is rich and incredibly alive. And Trnka’s use of camerawork and lighting are inventive even by today’s standards.

Břetislav Pojar, an animator on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, called it Trnka’s “most ambitious project.” When you remember that it was made without digital effects, the whole spectacle is hard to believe.

“Any errors or jagged movement of even one figure in one moment of a long scene would require re-animation and reshooting of the entire scene,” wrote Gene Deitch, an American director who lived in Prague. “Trnka was a perfectionist, and I was told that he had ordered many such reshoots during the long production.”

If the production was hard, though, getting to it was harder.

Trnka was what we’d now call a workaholic. After he began his puppet film career in 1946, he made almost a dozen of them in eight years, several of them feature-length. That was alongside his other projects. He often worked 16-hour days through those years, and burnout crept up on him. In 1954, he “reached his point of crisis,” Boček wrote.

Suddenly, Trnka lost his taste for puppets. “He began to hate them,” according to Boček, “for he had the feeling that they were overpowering him, and had become a burden under which he would stumble if he did not get rid of it.”

Trnka left animation for almost two years, becoming a full-time illustrator and developing his visual style in new directions. Ironically, his films rose in profile after he quit — official medals rolled in, and global distribution grew.

Trnka couldn’t stay away from puppets for long. As he illustrated, a film idea started to form. It would animate “his new liking for decoration, and for variety of shapes and colors,” Boček wrote. Trnka would adapt A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Pre-production was critically important for the film. Boček again:

In giving concrete form to his poetic vision he measured and measured again, five times, seven times, planning every detail. He has been called a poet, and with truth. But the basis of all art is craftsmanship, and Trnka’s craftsmanship is as solid and honest as that of a joiner or a blacksmith.

A report in 1956 explained that Trnka had already “produced a script complete with drawings and sketches,” and that he was in the process of building the puppets. They were plastic — a new form for Trnka, who’d worked in wood up to that time.

One thing about Trnka’s puppet-making hadn’t changed, though. Each puppet in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is meant to clearly be a puppet, rather than a person. Their faces don’t move. “I insisted on my own conception of the stylization of the puppets,” Trnka said of his technique, “always with an individual — but unchanging — facial expression.”

Pojar recalled that Trnka “gave [the] eyes an undefined look” whenever he painted puppets for his films. It lets their faces work like the masks in Japanese Noh theater. “By merely turning their heads, or by a change in lighting, they gained smiling or unhappy or dreamy expressions,” Pojar wrote.

Even after Trnka found it in himself to return to the studio in Prague, the challenges weren’t over. He’d been gone for almost two years — the team had aged out of apprentice roles and wanted to tell its own stories. Filmmaking had changed, too. Ultra-wide CinemaScope was in.

Adapting to CinemaScope was both a technical and an artistic challenge. Trnka had to switch from Agfacolor, which blurred in widescreen, to the much more expensive Eastmancolor. He learned the hard way that they worked differently — from the shades to the contrasts to the lighting. The team lost a lot of work, and Boček wrote that “many purely technical experiments had to be made,” bogging down production.

Trnka’s cinematography adapted as well. “He was not afraid to put two or three parallel events side by side, in the manner of a diptych or triptych,” per Boček. The whole screen was his canvas. The sets were vast and intricate — miniature worlds.

Deitch remembered seeing the materials for A Midsummer Night’s Dream before they were torn down, in all of their “stunning design and detailed workmanship.” To ensure that everything clicked on camera, he wrote, the team would first film each scene without any animation. Then they would shoot it all in motion.

Given all this, it’s not surprising that A Midsummer Night’s Dream took at least two years to make.

Trnka’s fame in Czechoslovakia made the extravagance possible. He was lucky enough to be the state’s favorite — at a time when the government, a communist regime, funded the arts. “No expense was spared” on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Deitch wrote. Trnka had the resources to fulfill his ambitions, and then some.

In recent years, Deitch recalled a party where Trnka opened a can of Russian Beluga caviar that “seemed the size of a snare drum.” To keep it from going bad the next day, they had no choice but to eat it all. Per Deitch, Trnka also enjoyed champagne:

Trnka drank a lot of champagne. As each bottle was emptied, he would hoist his ample body, walk steadily across the room, open a window and toss the empty bottle into the adjacent canal. Once, I happened to walk by his house when the canal was being drained in order to repair the broken stones lining the banks. As the water level slowly receded, an impressive mound of empty champagne bottles majestically arose.

Trnka’s eccentricity and brilliance both shine through in the finished film. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was his final feature-length project. The director who’d once reinvented 2D cartoons had proven that puppets could act out Shakespeare.

Below, you can watch A Midsummer Night’s Dream in full with English subtitles. We highly recommend it:

Today’s cover story was made possible by our members. With their support, we purchased the rare and invaluable book Jiří Trnka: Artist & Puppet Master (1965), our primary source for this piece. Thank you so much!

Joining our member community gets you access to our Thursday issues, where we dive even deeper into animation every week. Membership costs $10/month or $100/year. Students with .edu addresses can click here to receive a 40% discount.

2. News around the world

Animation saturation

Can there be too much animation? We’re in the process of learning the answer to that question. In an interview published this week, Jeff Ranjo of Netflix’s Maya and the Three made a telling comment about the state of the industry.

“For animation these days, because there’s so much coming out, it’s hard to really stand out,” Ranjo said. “And I think you have to put more in there to get an audience.”

Maya and the Three has managed to rise above the rest and become one of this year’s most exciting series. But, around the world, there’s a flood of animation that shows no sign of slowing down. Most series cannot be Maya. A lot will sink.

Just this week, Disney used its Disney+ Day event to hype up a ton of new animated shows. You can tell at a glance that they aren’t cheap cash-grabs — Disney is breaking the bank. On display were spin-offs for Big Hero 6, Zootopia, The Princess and the Frog and Guardians of the Galaxy. There are new Spider-Man and X-Men series on the way. The Proud Family is officially back (and looking slick).

Also, another Diary of a Wimpy Kid feature is coming. (The first one isn’t out yet.)

Disney is loading its streaming service with an unbeatable slate of animation. The thing is that Disney+ is just one platform, and Disney is just one company, but everyone is using the more-is-more strategy for animation — globally.

Back in September, Observer published a piece called “Here’s How We’d Run a New Streaming Service.” It pointed out that animation wasn’t part of their gameplan. “Animation is a major battleground of the streaming wars,” the article explained, “but so saturated across the main combatants (plus Crunchyroll) that it doesn’t make much sense for us to chase that rainbow.”

Again, saturation is global. Russia’s Soyuzmultfilm has resurged in the last few years by pouring out “thousands of minutes of animation,” and we saw news this week about three of the feature films the studio is making right now. It’s only one of the Russian companies doing the same.

Meanwhile, Japanese anime is having an “overproduction crisis,” to quote Callum May of Anime News Network:

Producing an anime has never been less risky, and this has prompted an overproduction crisis that exists as a combination of streaming services’ ever-increasing demand for more content, coupled with the anime industry’s continuing issues with overwork. These issues haven’t fazed the industry, however. This year, Kadokawa announced that they were aiming to produce 40 anime each year until 2023.

The same patterns are playing out in countries like China, where animation production is booming — but much of it struggles to break through.

Is it sustainable? In the age of streaming, maybe. As long as streamers still bankroll new series, it doesn’t really matter whether anyone sees them. And the setup is giving people a shot who didn’t have one before. Artist Pablo Leon, whose opinion we take very seriously, tweeted in July that “more people from different backgrounds have gotten a bigger chance to break in [during] the last 5 years than anything before 2013” — which he attributed to the animation boom.

So, right now, it’s too early to say where the boom is headed. “The reality is that the demand does still exist and, unfortunately, overproduction will continue,” Callum May wrote in September about the anime industry. “Deep down, we still want to be able to scroll through the largest library of entertainment in human history and complain that there’s nothing to watch.”

Best of the rest

There were several big losses this week. Bob Baker (82), the legendary writer of Aardman’s Wallace & Gromit, passed away on November 3. We also lost actress Yoshiko Ohta (89), known for voicing projects like Himitsu no Akko-chan, and Mystery of the Third Planet animator Dmitry Kulikov (75).

In Japan, the studio dwarf (Rilakkuma and Kaoru) is working on a stop-motion series called Rilakkuma’s Theme Park Adventure. It’s due on Netflix in 2022.

Five animated features are up at the European Film Awards in Germany this year — the most ever. Among them are Flee, Wolfwalkers and Where Is Anne Frank.

Rooty Toot Toot, the seminal cartoon by the American studio UPA, is turning 70 this month. Animation Scoop has shared a high-definition copy to celebrate.

A TV channel that reaches over a billion viewers, CCTV-14 Kids in China, is set to broadcast The Day Henry Met by Irish studio Wiggleywoo.

In a new interview, the producer of China’s Scissor Seven talks about the show’s international success. The United States and Canada make up around “one-third of the total number of overseas fans,” she says.

Speaking of international success, the overseas market for anime is now larger than the one in Japan, according to a new report.

One more from Japan — there’s a trailer for the fourth season of Aggretsuko, which premieres on Netflix on December 16.

The animators of Bombay Rose, Paperboat Design Studios in India, are now majority-owned by a Singaporean company.

Lastly, the CG film Mila is up for Oscar consideration. Per Animation Magazine, Mila took a decade and was made “with the help of 350 volunteers across 35 countries” — including places like Nigeria, India, Italy and Malaysia.

3. Last word

That’s the end of our issue today! Thanks for reading. We’ll be back next Sunday — and on Thursday, for members.

One last thing. This is the second week in a row that a Sunday issue has beaten our wildest projections. Last week’s story about Samurai Jack’s backgrounds was one of our biggest successes ever — thank you all!

There were way too many kind messages to include them all here, but we did want to mention two. In a tweet, director Peter Ramsey (Spider-Verse) wrote, “Great piece on this spectacular work.” Meanwhile, the always-awesome Bob Flynn tweeted:

… it’s worth mentioning once more how well-documented, curious and thought-provoking these newsletters are. I learn something new every time. Even on subjects I think I know pretty well.

We’d like to thank them — and everyone who enjoyed and shared the piece. Your support makes this newsletter possible.

Last month’s issue about Cartoon Modern is still spreading, too. Our fellow Substack writer Máximo Gavete, a designer in Barcelona, recently wrote up some compelling thoughts about the book and Rhapsody of Steel in his Spanish-language newsletter. If you haven’t picked up your free copy of Cartoon Modern yet, it’s available to download right here.

Hope to see you again soon!

From Politics, Art and Commitment in the East European Cinema — another book we were able to purchase with the support of our members.

Thanks for the great article, just for information, there is also a book with larger reproductions from the movie https://www.amazon.com/Midsummer-Nights-Dream-Eduard-Petiska/dp/B009IJQAZI

I first learned about Trnka through my obsession with the work of the brothers Quay (perhaps we'll read about them too here one day!). It's interesting to read about the messy aspects of production in Trnka's work—the lost progress, the backtracking, the need for experimentation, navigating new technology—as well as his accolades and eccentricities.

As a side note—I've been hearing about the Samurai Jack issue from multiple corners of my network, even outside of the general animation/visual arts sphere. Surely a testament to the great work you're doing, congrats! How exciting to share, at increasing scale.