Welcome! We’re here with a new Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. The agenda:

1) Where to start with the Czech icon Jiří Trnka.

2) Animation news from around the world.

Before we begin — anyone interested in Soviet-era animation should check out Animatsiya. It’s a site (run by a veteran translator) that legally overlays subtitles onto YouTube and Vimeo embeds. The catalog is still updating after years and is full of classics like Tale of Tales, The Little Mermaid and Puss in Boots. An amazing resource.

With that, here we go!

1 – Trnka in brief

Stop motion is the most versatile type of animation. It can take nearly any form: the Pixar-like polish of Coraline, the unsettling mishmashes of Jan Švankmajer, the beauty of Hedgehog in the Fog. It’s existed for more than a century, and its magic persists.

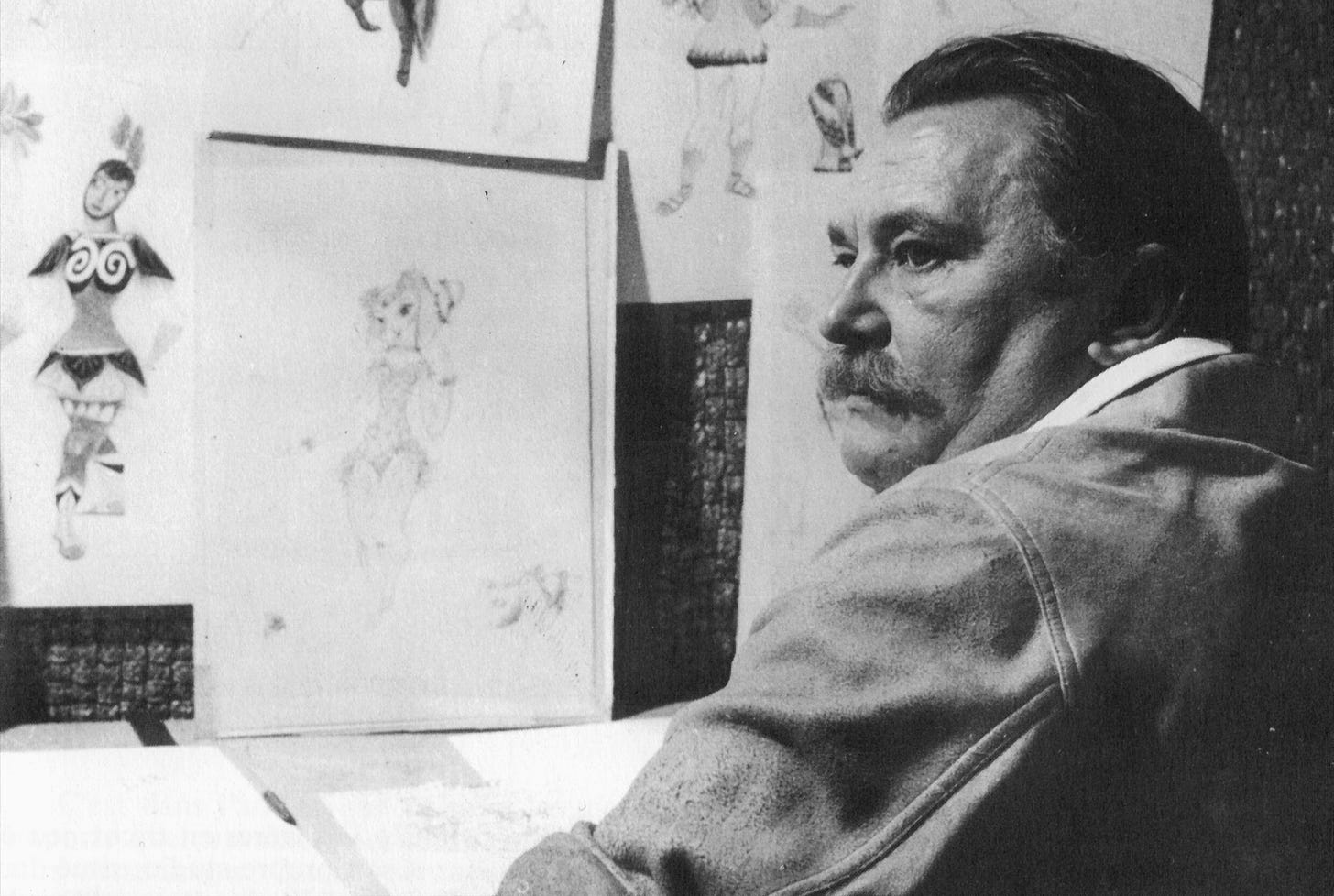

But there’s something odd in stop motion’s history. Its defining artist, the person most responsible for proving its power, is now mostly unknown. His name was Jiří Trnka. And there’s no getting around him.

Not many today have heard of Trnka, but they’ve felt the effects of his work. He had a deep impact on the directors of Coraline and Hedgehog in the Fog, and he established the stop-motion community that gave birth to Švankmajer. He even helped to inspire Rebecca Sugar and Pixar — Jan Pinkava (Ratatouille, Geri’s Game) admits that he was “hugely influenced” by Trnka. These are just a few examples.1

Trnka, whose animation career went from the ‘40s to the ‘60s, worked in Prague. In his day, he was world-famous. He didn’t direct hits, but he had a name.

As Newsweek explained in 1966:

… Trnka is the most celebrated animator in Europe, a latter-day movie magician who, like the great Georges Méliès, is at once writer, painter, sculptor, mechanic, director and film editor. Chilean poet Pablo Neruda has called him “one of the contemporary world’s greatest poets,” and a number of critics rate him second only to Charlie Chaplin as an all-around film artist.

Trnka helped to overturn the Disney model of animation. He was an auteur who used puppets to tell the stories that Disney wouldn’t or couldn’t. Even now, his work stuns.

But it can be hard to know where to start with it or how to approach it. So, today, we’re offering a brief introduction to Trnka and his talent — with links to watch key films and sequences on YouTube and the Internet Archive, subtitled.

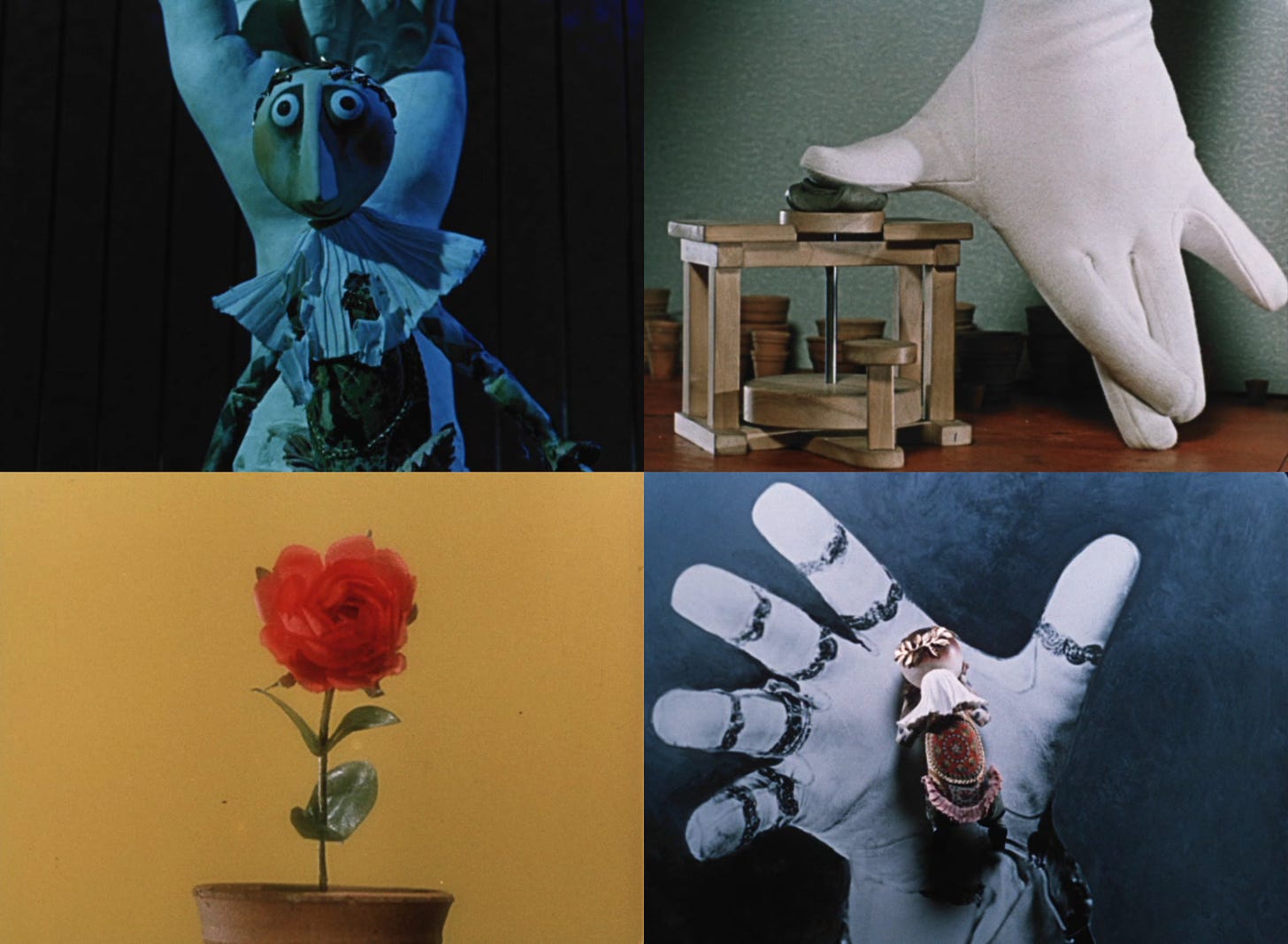

If you’ve ever heard of Jiří Trnka, you’ve heard of The Hand (1965), the most famous and darkest of his films, and the last before his death in 1969. It stars an artist-puppet. A human hand badgers, coaxes and threatens him to build a statue in its honor. The puppet gets rewarded when he gives in. But giving in is unbearable.

It’s a wordless story about power, inspired by real life. When The Hand debuted, Trnka was the most revered artist in communist Czechoslovakia. His work was state-funded, and he had a degree of leeway. “We are free to create according to the abundance or limit of our imagination,” he said in the mid-1960s. Yet he was unhappy.

Although Trnka was leery of the state, its officials co-opted his every victory. They saw him as a tool — he was turned into a celebrity, a symbol. Trnka had “unwittingly become a part of the communist machinery, and he knew this full well,” in the words of one writer. The Hand was his protest.

But its target was bigger than Czechoslovakia or even communism. Trnka was disillusioned with power around the world. As he wrote:

... the hand is not admiral or papal or political, but simply the hand that has power … It is omnipresent, it has always been, regardless of nationality, all over the world, and it forces each individual to do what they do not wish to do. Something sweeps through history, perhaps an institution, convinced that its truth is the universal truth, demanding attention and requiring everyone to agree with it. It explains the whole world to a person in its own way, presents a crystallized opinion and ready-made explanation and view of things, and won’t permit anyone to have their own opinion. The victim could be anyone from antiquity, or Galileo Galilei, at another time Oppenheimer, etc.

It’s a spare, unsettling film powered only by two characters: the puppet lead and the hand (animated through “pixilation”). Many have called it Trnka’s finest work.

But it’s too easy to label The Hand as his career high and ignore the rest. The truth is, he made classics for two decades. And he always had something to say. “[M]y films are current, even if no one noticed or wanted to notice,” as he put it.2

Trnka’s animation career got started in 1945 — just after the fall of the Nazi occupation of Prague. At first, he and his colleagues worked in 2D animation.

By their third cartoon, they were “consciously” rebelling against Disney, Trnka said. That was The Gift (1946), a reality-warping film with a modern graphic style. It’s akin to UPA, but Trnka and his team got to these ideas independently.

The Gift is a satire about creativity. It opens in live action: a writer finishes his script but, fearing what the producer will say, he tweaks and censors his work in bizarre ways. We see it happen through a cartoon that changes to fit his edits. The resulting film broke ground and became a driving influence of the Zagreb School of Animation.

Cartoons weren’t Trnka’s passion, though. His roots were in puppetry. As a young child in the 1910s, he’d created dolls with two local girls — his mother wrote that he was good with a sewing machine by age seven. A few years later, he apprenticed under a puppeteer and joined the tradition of Czech puppet theater.

Not long after The Gift, Trnka returned to those roots. He decided to make stop-motion puppet films. His first was The Czech Year (1947), a feature-length musical. From its opening sequence, even its first shot, something is clearly different than before.

These aren’t flat drawings anymore: the staging, camera movement and depth of field place us in the action, viscerally. The editing is rhythmic, expressive. Nothing here is Disney or UPA — it’s more like Eisenstein or Orson Welles. “I left cartoons because I wanted to use space and light, just everything that the third dimension brings,” Trnka said.3

It gave his work a sense of reality. Even so, Trnka believed that puppets shouldn’t be animated or designed like real people. These aren’t “miniature humans,” as he saw it: they have “their own world” inherited from puppet theater. For him, an animated puppet with a fully articulated face is “a little monster.” His own puppets have painted and carved still faces. Like with Noh masks, light and angle bring out different expressions.

So, like Trnka once said, his films star only “living puppets, that is, puppets as such.” He argued:

On the whole, one may say that puppets are utilized to the best effect where a realistic presentation on the screen often places insurmountable obstacles in the way of convincing performances by humans. It is no mere chance that puppet films are most successful not only in the field of biting caricature and satire, but also in extremely lyrical tales and in those whose subject demands the portrayal of emotional fervor. ... I cannot imagine how the grand passion of the scenes from the Czech mythology ... could be conveyed as stirringly in a live-action film.4

To understand how powerful Trnka’s discoveries were, you only need to fast forward a little to his feature Old Czech Legends (1953). It’s an epic set in ancient times — and a showcase of his filmmaking. Two sequences illustrate the point.

One is the torment of Neklan, a cowardly prince. A barbarian army, led by the warlord Vlastislav, approaches his walls. We watch as Neklan panics alone in his room. The sequence begins with an unbroken, two-minute shot. We wrote last year:

… the camera and character are alive in three-dimensional space — with all the light, shadow and depth that entails. Neklan’s movements through this space are blocked and choreographed like those of a live actor. The camera pursues him around the room, spinning and zooming and panning and tracking, even as he tries to escape.

Trnka composed the sequence, then handed it to his top animator, Břetislav Pojar. It became a masterpiece of animated psychology. To quote one critic, Neklan is the “incarnation of anguish, cowardice and fear; animated by Pojar, he takes on Shakespearean dimensions.”5

Then there’s the horseback battle, which comes soon after. Neklan sends his servant Čestmír to lead his army. A brutal fight ensues. At the end, Čestmír duels Vlastislav while the sun sets. Their bodies tangle and their horses twist in the dust, mirrored by an injured raven on the ground. It’s slow, melancholy. We’re in it with them — there’s an intense sense of presence and space. Again: it’s visceral.

In these sequences, Trnka used techniques that wouldn’t be mainstream in animation for decades — not until Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata took over.

In a recent interview, a French director spoke about Miyazaki’s and Takahata’s approach to staging and filmmaking. He called it “spatial cinema, which uses the full range of what film language can do.” As he said:

… what Disney set up in their first films is what I call “pictorial staging”: the staging isn’t made to create a sense of space; it’s made to create beautiful pictures. Which means flat, most of the time, rather than in-depth … which is the complete opposite of what Takahata and Miyazaki do. … So for me, as a director, I have to face this question: can I invite the spectator inside the world I show them, do something more than just say, “You’re watching something from far away”?

Takahata first did this in Horus: Prince of the Sun, released in 1968. Trnka had discovered it by the ‘40s. In fact, the Horus team screened Trnka’s films and took visible influence from his work. Reiko Okuyama (the number-two idea person on Horus) was a major Trnka fan and brought his style to her art for the film.6

Trnka’s impact on Horus wasn’t a one-off. His films were magnetic to artists that way. In the ‘50s, they amazed China’s animators, and a man named Qian Yunda was sent to learn the secrets of Czech animation from Trnka and others. Qian became a major director in China, as did Jin Xi, a fellow Trnka fan who visited the Prague studio.7

In this same era, a Trnka feature called The Emperor’s Nightingale (1949) reached Japan, and a young Kihachiro Kawamoto happened to see it. He grew obsessed with stop motion and traveled to Prague to become Trnka’s apprentice. “He was like a god figure for me, so it was difficult to talk to him naturally,” Kawamoto remembered. But Trnka put him on track to become Japan’s own god of stop motion.

That was the thing about Trnka. He was quiet and looked imposing, but he was also kind — and he had a sense of humor. He could follow a film as grand as Old Czech Legends with Two Little Frosts (1954), a very funny slapstick comedy. It’s different not just in tone, but in medium: an innovative blend of puppet animation and flat cutout characters.

Trnka was an experimenter, and always an auteur, but not a difficult one. Břetislav Pojar recalled the studio as “very friendly and homely,” and Trnka as “a man who was calm.” Another of Trnka’s star animators, Vlasta Pospíšilová, said this about him in the ‘80s:

I don’t really do anything but remember him. I admired him terribly. The cameraman lit the scene for him, [Trnka] came and waited, and around him and behind him stood a crowd of people in awe, watching him create. They were people not only from the studio, but also from elsewhere. For me, he was the biggest personality that marked my life. Creative and personal strength emanated from him.8

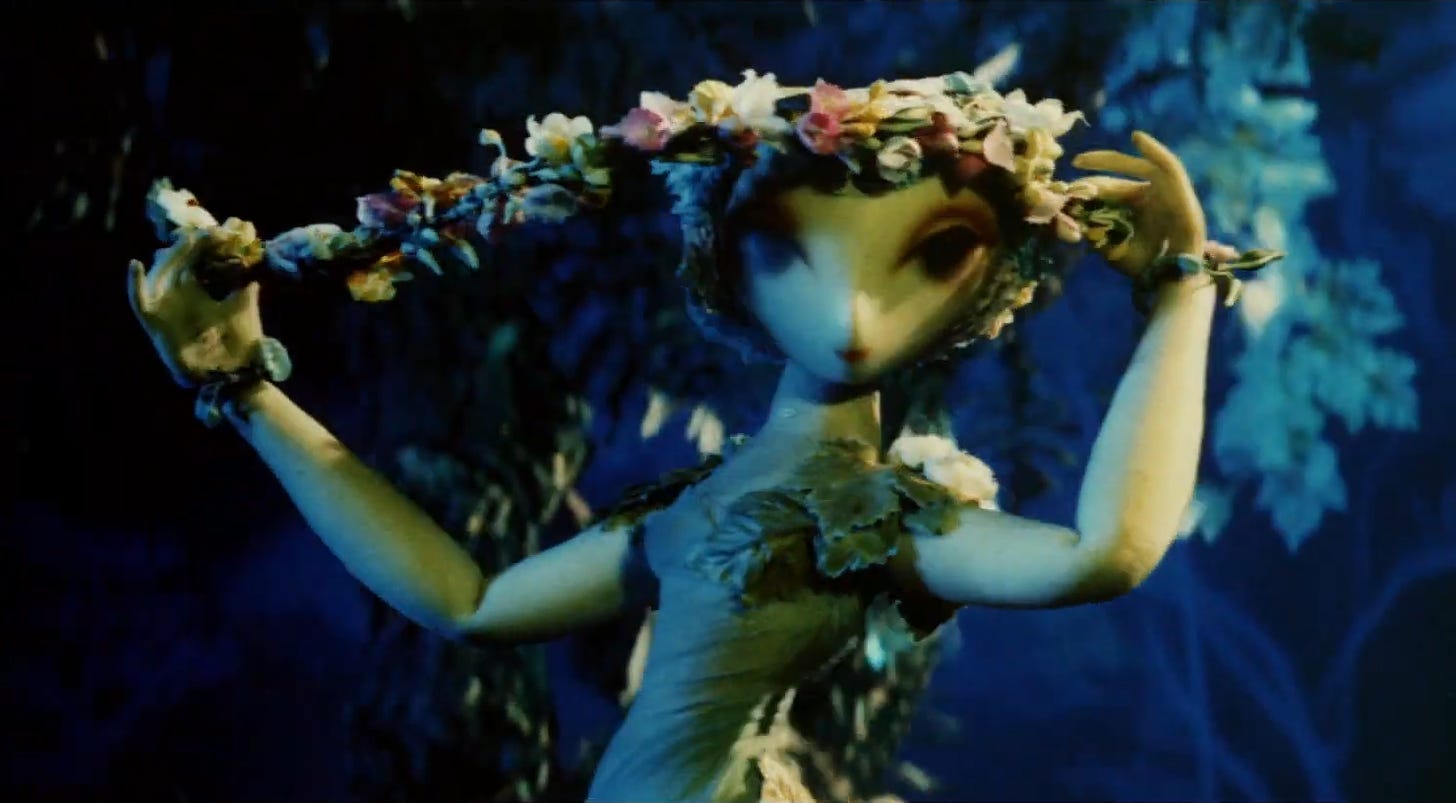

Pospíšilová animated on Trnka’s final feature, and possibly his biggest challenge: A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1959). It’s a giant, super-elaborate work — one of his best. He turned Shakespeare into a “puppet ballet,” rich with hallucinatory colors and effects. You can’t really look away.

At that time, Pospíšilová was a newcomer, but she quickly rose under Trnka. Like so many of his disciples, she later became a director herself. This was her memory of Dream’s production in the ‘50s:

Trnka was good at telling the animator what to do in such a clear way, at least for me, since I still wasn’t very experienced, but he was really good at explaining in a calm voice, without any particular emphasis, that voice really got through to you. And so my beginnings were pretty good all thanks to him and his impeccable direction. And this was also true for the experienced animators. He also explained things to them... but each animator had his own sector and Trnka, or rather the Master, already knew what to assign and to whom. And he would assign the whole scenes to them. He knew how to describe, to explain in detail, the character to be animated.

The films above are a tiny slice of Trnka’s filmography. He was a workaholic, with an output speed several times higher than that of most artists. “I’ve never had any hobbies in my life,” Trnka once said. “I have nothing else in the world to do but to work without end. I even get bored when, during a trip abroad, I have one or two hours free.”9

His two-decade career produced many other classics: The Chimney Sweep (1946), The Song of the Prairie (1949), Prince Bayaya (1950), The Cybernetic Grandmother (1962) and more. But that work, like most of the work already mentioned, is hard to find in great quality or with great subtitles. Restorations of The Czech Year and Old Czech Legends have been released on DVD and Blu-ray in France, but even those aren’t available to most.

Slowly, over the decades, this availability problem has disappeared Trnka. It’s a vast loss, hard to compare to anything else in animation. The masters tend to have their work well preserved and properly released.

There’s no doubt that Trnka’s films can take commitment: he had his own approach, more meditative and less immediate than Disney’s. But you can gain a lot by watching just one of them, even a single scene. While Trnka’s art and ideas may be obscure now, they haven’t lost their specialness. They’re treasures, awaiting rediscovery.

2 – Newsbits

Check out the trailer for The Glassworker, the long-awaited, Ghibli-inspired Pakistani feature. “We have created a studio alongside a film in Pakistan through grit and passion for the craft,” says producer Khizer Riaz.

In America, a new round of CalArts student films has hit YouTube. Check out Play With Me by Julie Zheng — it has a very fun (and well-animated) gloopiness to its motion and forms.

A mess in Spain: over 60 artists from the former Ilion Animation have, reportedly, been left uncredited on the major film Dragonkeeper. The story hasn’t gotten much traction in English yet, but it’s been unfolding for a while, with no end in sight.

The next Wallace & Gromit film will be previewed in France at Annecy, happening in June.

More news from Annecy in France: its feature competitions will include The Storm (the latest by Busifan), The Glassworker, Studio Ponoc’s film The Imaginary and more. Screening out of competition is The Worlds Divide by solo animator Denver Jackson. See the full list.

Speaking of The Imaginary, this Japanese film is set to hit Netflix on July 5, internationally. It comes from ex-Ghibli director Yoshiyuki Momose and uses a visual style inspired by Klaus.

In Russia, stop-motion animator Stanislav Sokolov (Hoffmaniada) is doing a new film called Bulgakov. It’s reportedly 13 minutes long — the team started a crowdfunding campaign on Planeta for the last three minutes, but it’s drawn surprisingly little attention in Russia.

In other crowdfunding news, a cool-looking short called Naledi (South Africa) reached its Kickstarter goal in short order this week. See the campaign here, and a trailer here.

Lastly, we wrapped up our series on Don Bluth — adding a bit more to the story, and looking at his fight against Disney’s single-minded focus on key animation.

See you again soon!

Henry Selick mentioned Trnka’s influence in this archived interview, while Yuri Norstein once called The Hand his favorite film (according to A Reader in Animation Studies). Rebecca Sugar cited the influence of The Hand in this discussion. The blockquote after this comes from Newsweek (March 28, 1966).

References for this second part of the article: Séquences (February 1966), Kultura (September 18, 1957), Film a doba (August 1965) and the book Jiří Brdecka: Life – Animation – Magic (thanks to Toadette for the last one).

From Film a doba (February 1979), a key source. The use of three-dimensional space was one of several benefits that Trnka saw in switching to puppets. As he said in Film Culture:

... I am firmly convinced that puppet films keep much closer to the author’s original manuscript in the portrayal of the figures, and that they make possible a much richer use of the imagination in the facial expression. This corresponds fully to the kind of lyrical film for which I have been striving since the outset of my film career. I should like to add, moreover, that in cartoons the different techniques of the many draftsmen participating in the actual piecing together of the film obscures the character of the original drawing. Apart from this, the very nature of cartoon figures calls for continual motion; it is not possible to stop them, and neither is it possible to bring them into a state of contemplation.

Other references for this third section: Film a doba (June 1965), Film Culture (Winter 1955), Japan Media Arts Plaza, Cahiers du cinéma (February 1960) and the books My Son, Jiří Trnka: Artist & Puppet Master and Z Is for Zagreb.

This is Marie Benešová in a November 1975 pamphlet published by the Cinémathèque québécoise.

We wrote more about the links between Okuyama and Trnka, and the style she borrowed for her Horus art, in back in March. There’s a lot more to be said about the similarities between Horus and Old Czech Legends, though, from the look of Horus’s village to the caped, helmeted villain and his army of wolves.

Details about Qian Yunda’s time in Czechoslovakia come from his interview in the book We Animators (身为动画人). He cites Trnka’s film series The Good Soldier Švejk as the one that really wowed China’s animators and got him sent to Prague. Jin Xi’s connections to Trnka are discussed here. Meanwhile, Kawamoto’s apprenticeship under Trnka was the subject of an article we published in January. See his interview here as well.

From Film a doba (July 1983). Pojar’s description of Trnka comes from a 2004 television interview. Pospíšilová’s other quote is from a YouTube documentary by Materia Films.

From Image et son (June–July 1969).

Lovely article! By the way, I am looking for a stop motion movie featuring animals as protagonists. I can remember a couple of things: the first scene opening in an amusement park, with frogs running on motorcycles in a barrel, and the last scene where the protagonist fought against an evil wizard who was a monkey (the only real animal in the whole movie). I think it was an eastern bloc production, but I have never read about it on the internet.

Omg this lead story image hit my heart like an arrow, what a visual memory from my childhood! As kids we had these taped-to-VHS programs (from U.S. PBS maybe?), an anthology series called “Long ago and far away.” They were different animations, from different countries. Many spooky, we loved them and watched them endlessly. I’m certain some of his work must have been in those programs, maybe in snippet forms with English dubbed over. The description about the fight and the raven on the ground sounds familiar. I will watch the YouTube versions and try to recognize one!