Welcome! It’s a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And this is the slate today:

1️⃣ The revival of Zagreb animation.

2️⃣ Animation news from around the world.

3️⃣ [MEMBERS] A look back at Seers and Clowns (1994) by Faith Hubley.

Joining us for the first time? It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — you’ll get them right in your inbox, every week:

With that, we’re off!

1. Zagreb in HD

The animation world has had plenty of excitement in 2022 — and not always the good kind. You’ve read the year’s headlines, maybe felt the tremors yourself. Still, 2022 has given us at least one exciting twist that’s unquestionably great, without much press at all.

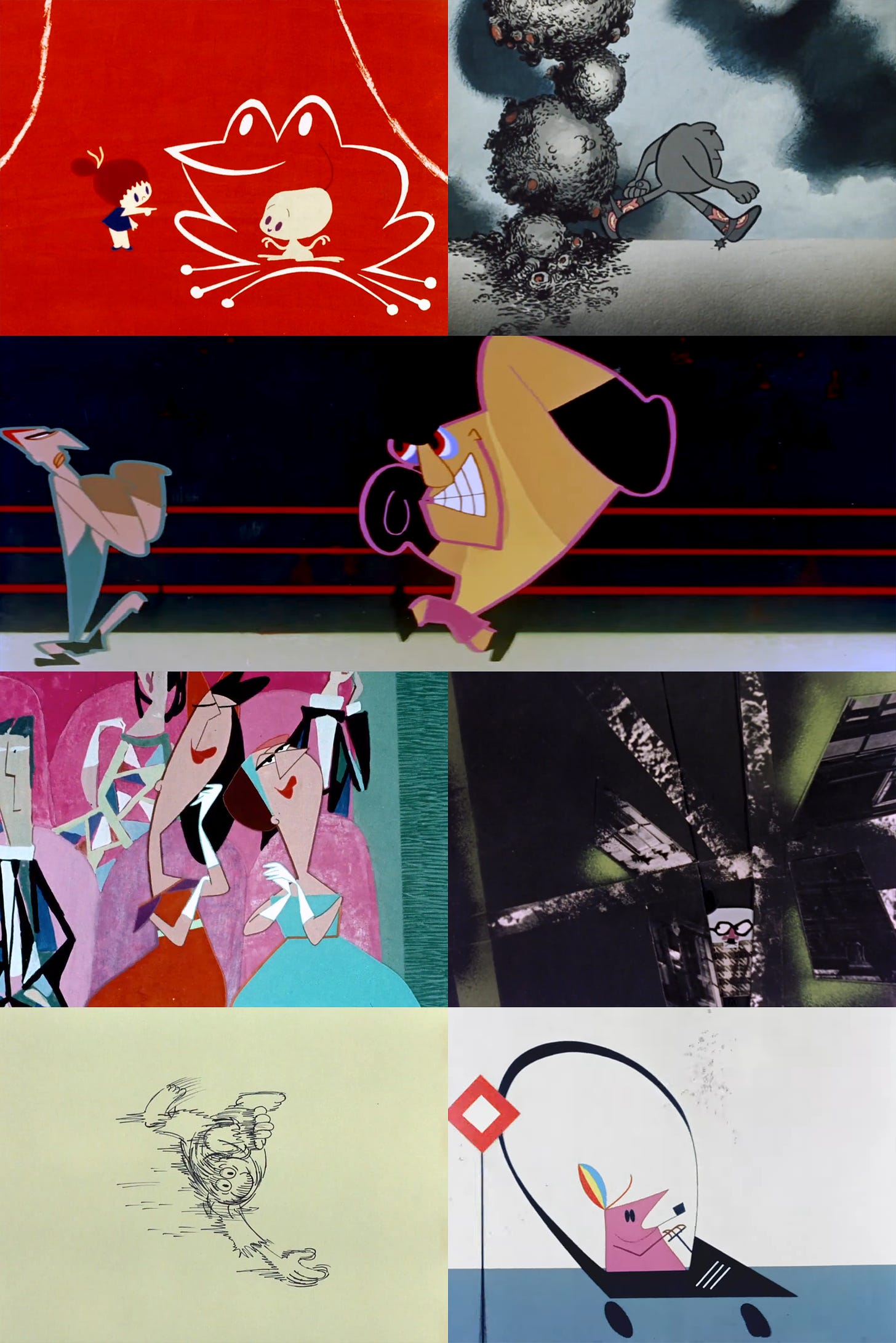

The films of the Zagreb School of Animation have returned on YouTube, restored, for free.

Let’s back up. If you’re not familiar with the Zagreb School, it was a movement that remade this medium. Inspired by UPA, it built cartoons that were radically new and different. It started during the ‘50s in Yugoslavia, a communist country that no longer exists. Quickly, the influence of this animation spread across the globe.

Many insiders have long admired and prized the cartoons of the Zagreb School. For decades, they’ve been rare — or stuck in shabby quality. But that’s finally changing. Last month, we wrote about the revival of the Zagreb classic The Masque of the Red Death (1969). We’re happy to report that it was just the tip of the iceberg.

Today, we bring you a tour of some of the gems restored so far — linking each title to an official YouTube upload, and offering context along the way. There’s never been a better time to rediscover the Zagreb School.

This movement centered on one studio: Zagreb Film’s cartoon division. Its early employees weren’t traditionally trained in animation — they had varying backgrounds.

Director-animator Dušan Vukotić, the School’s leading light, studied architecture and had a career as a magazine cartoonist. Writer-director Vatroslav Mimica came from live-action films. Nikola Kostelac, another director, had been a working architect. And director Vlado Kristl, whose films are still to be uploaded, was an avant-garde painter.

That’s just a few of them. Defining a group this out-there as a “school” is tricky — their work is all different. People have argued about the name since it first came into use. For his part, Vukotić offered this description of the Zagreb School in 1962:

Our cartoons, first of all, are characterized by the diversity of graphic treatments and the variety of directing processes. Then there is the expanded, or rather unlimited, range of subjects that these films cover. The next characteristic is the style of animation, which is not based on real-physical movement — that is, on the anatomical law of motion. Fourth and very significant is the absence of words. Our films are made without accompanying voiceover lines or dialogue. All verbal solutions are replaced by graphic, visual ones, which eliminated language barriers. The cartoons of the “Zagreb School” are accessible and understandable to all viewers of any country. These basic characteristics undoubtedly speak of something common in our films, and whether someone calls it a way, a concept or a school — it makes no difference.1

Basically, this stuff follows its own rules. It’s weird. It’s dogmatically anti-Disney. It often features stories never previously tackled in animation. The films don’t look normal, and they don’t even sound normal — as Vukotić once said, animation that doesn’t imitate real motion requires abstract sounds that “do not imitate real noise.”

You find this in Vukotić’s Piccolo (1959), a barrage of graphic and audio invention from start to finish. Two neighbors enter an all-out musical war — it’s irresistibly insane. By the time one of them cuts rain out of the sky with scissors, and gets drunk on gin to hallucinate a second mallet for his drums, you can’t turn back.

Many of Zagreb Film’s big wins came from Vukotić. His earliest hit was Cowboy Jimmy (1957), a satire of Westerns that drew global attention at festivals. It showcases common parts of the early Zagreb style — like limited animation “on ones,” which we broke down in a members-only issue. It’s fluid and unnatural, with huge gag potential.

Vukotić carried these ideas further in Ersatz (1961), an Oscar winner set in a world where everything — everything — is a cheap imitation filled with air. It was this film that inspired the Worker & Parasite bit from The Simpsons, although the jokes in Ersatz are quite a bit more accessible than that.

Even better than Ersatz, though, is Vukotić’s film Cow on the Moon (1959). In some ways, it feels like the Yugoslav precursor to Dexter’s Laboratory — only with Dexter as a girl and Dee Dee as a boy. The visual gags, like the moment when the scientist girl runs outside the film’s frame to tilt the background painting, are undeniable.

In the talk around Zagreb Film, Vukotić gets a lot of hype — for good reason. But he had real competition: the studio was a creative hotbed. As Vatroslav Mimica recalled:

There were five or six teams making cartoons — director, main designer, main animator… We walked from one to the other. It was constant brainstorming, a constant exchange of experiences — what are you doing, what are you thinking, what are you planning, I would do it this way, I would do it that way. Each sought their own individuality, and yet they shared a common spirit.

Mimica wrote for Cowboy Jimmy, and he became a top director himself — one with a different style than Vukotić. Mimica’s films are slower, more meditative and often more adult-oriented.

You see this in Alone (1958), a Zagreb masterpiece. Amid the modern graphics and indescribable soundtrack, it’s a beautiful film — in its own way. It’s a parable about a man who gets sick of his fellow humans, and the office co-worker whose love he rejects and ignores. Then he has a terrible dream where he’s truly, fully alone, at last. When he wakes up, he realizes that he has to accept the love that the world offers him.

Also lovable is At the Photographer’s (1959), a funny and kind-of-melancholy story about a man trying, and failing, to smile for the camera. Graphic innovation drives it — seeing how the animators move the shapes is endless fun.

In Mimica’s own view, two of his very best cartoons were the mysterious, hard-to-place Everyday Chronicle (1962) and The Inspector Returns Home (1959). Both are clearly aimed at adults, and both are masterworks of collage animation. Like Alone, they’re about the modern world. The Inspector, especially, is a hypnotic watch unlike anything else at the time.

Alongside Mimica and Vukotić, Nikola Kostelac directed some of Zagreb Film’s wildest pieces — and some of our favorites. His early film Opening Night (1957) was “a major breakthrough” for the Yugoslavs, helping to set the course for their experiments in graphics and motion.2 When we mentioned Opening Night in January, we wrote:

Although Kostelac’s team designed and drew the characters as graphic shapes, every movement distorts them. The principles of animation fly out the window — characters slide from pose to pose in a stop-start way that’s at once funny, surreal and off-putting. Seen today, the style looks almost like vector animation generated by a rogue AI.

Maybe even more reckless is Kostelac’s Ring (1959), a film whose look needs to be seen to be believed. Far from using “limited animation on ones,” lead animator Leo Fabiani drew quite possibly the most chaotic motion ever put to mid-century graphics. His disregard for forms, volumes and model sheets can only be compared to Jim Tyer. This is a rare cartoon, new to us, and we can’t stop thinking about it.

This is just some of the treasure on Zagreb Film’s animation channel. There’s a lot to take in.

It should be said that the channel isn’t perfect, though. Vukotić’s great Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun and An Avenger (both 1958) have serious sound-sync issues right now. Many major works, like Vlado Kristl’s Don Quixote (1961), aren’t online yet.

One other trouble simply comes with the territory: not every Zagreb School cartoon measures up to Alone or Cow on the Moon. As it continued into the ‘60s and ‘70s, some of the newer work leaned into vague, easy cynicism — someone today might call these “we live in a society” films. At times, the complexity of the early stuff went missing.

Even then, there were classics. Zlatko Grgić’s A Visit from Space (1964) is charming, with wonderful design — aimed more at kids than most Zagreb Film pieces. Tamer of Wild Horses (1966) by Nedeljko Dragić, with a script by Mimica, is another enigmatic beauty in the collage vein. And Dragić’s later film The Day I Quit Smoking (1982) is a jaw-dropping technical display, in which the hero navigates a world we can’t see.

All are worth watching. There are notable cartoons on Zagreb Film’s channel that we haven’t linked here, too — it’s hard to pitch oddities like Vukotić’s Ars Gratia Artis or Grgić’s Klizi-Puzi. We invite you to explore the channel for yourself. It’s still being updated, so there’s no telling what the coming months will bring.

We’ll be watching. At its best, the work of the Zagreb School of Animation is as inspiring today as it ever was. We don’t see ourselves getting over the opera singer from Opening Night any time soon.

2. Newsbits

Indie Spotlight: Bearpuncher. Director-animator Daniel Haycox emailed us about this film — we enjoyed it. Strong bones, a well-told story and visual highlights like a cute fire-fawn cryptid. It gets our recommendation.

American actor Kevin Conroy, known as the iconic voice of Batman in dozens of projects (including The Animated Series), passed away at age 66.

Canada’s GIRAF Animation Festival begins Nov. 17. Besides its competition, it has stop-motion workshops with Evan DeRushie, a main figure on the brilliant Shaman’s Apprentice. (We were part of GIRAF’s jury last year — a great time.)

One of the most unique and obscure stop-motion features of the 2010s, Spain’s O Apóstolo, is now online for free — subtitled in over a dozen languages.

Don’t miss the new episode of Bigtop Burger by Ian Worthington (America) or the Netflix premiere of My Father’s Dragon by Nora Twomey and Cartoon Saloon (Ireland). Twomey talked about her film’s goals and trials in a big AWN interview.

Foreign distributors are getting less skittish about buying Russian animation, claims producer Roman Borisevich, although Poland and the Baltics are “still difficult.” Meanwhile, the State Duma works on a draft law to offer full state funding to children’s films, and Putin ominously says that animation for kids needs to feature more Russian heroes to instill patriotism from a young age.

In Mexico, voice actor Carlos Segundo (known for his Spanish dub of Piccolo in Dragon Ball Z) calls for better conditions in dubbing. He writes that home studios need to stay the norm even as COVID-19 winds down in his country.

We noted last week that Japanese director Hiromasa Yonebayashi (Arrietty) was hospitalized after colliding with a car on his bicycle. He’s since undergone a successful surgery and been released from the hospital.

Japan’s One Piece Film: Red is making a splash at the foreign box office, hitting #1 in Saudi Arabia and #2 in America. On that note, the profits of the anime industry reached a record high in 2021, per a new report.

More from Japan: Studio Ghibli released a Star Wars short on Disney+, Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki has a new book coming and Suzuki’s eldest daughter is writing about their life — like the time she penned lyrics for Whisper of the Heart.

Lastly, our issue on the All Caps video sparked a very cool, thoughtful discussion from the podcast In Search of Sauce, which focuses on standout music journalism.

3. Quick look back — Seers and Clowns

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.