Welcome! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s the plan today:

One — the decade-long production of Irish classic The Secret of Kells.

Two — animation news from around the world.

Three — the last word.

If you’re new, you can sign up to receive our newsletter every week, right in your inbox:

That said, let’s get going!

1. Animating Irish tradition

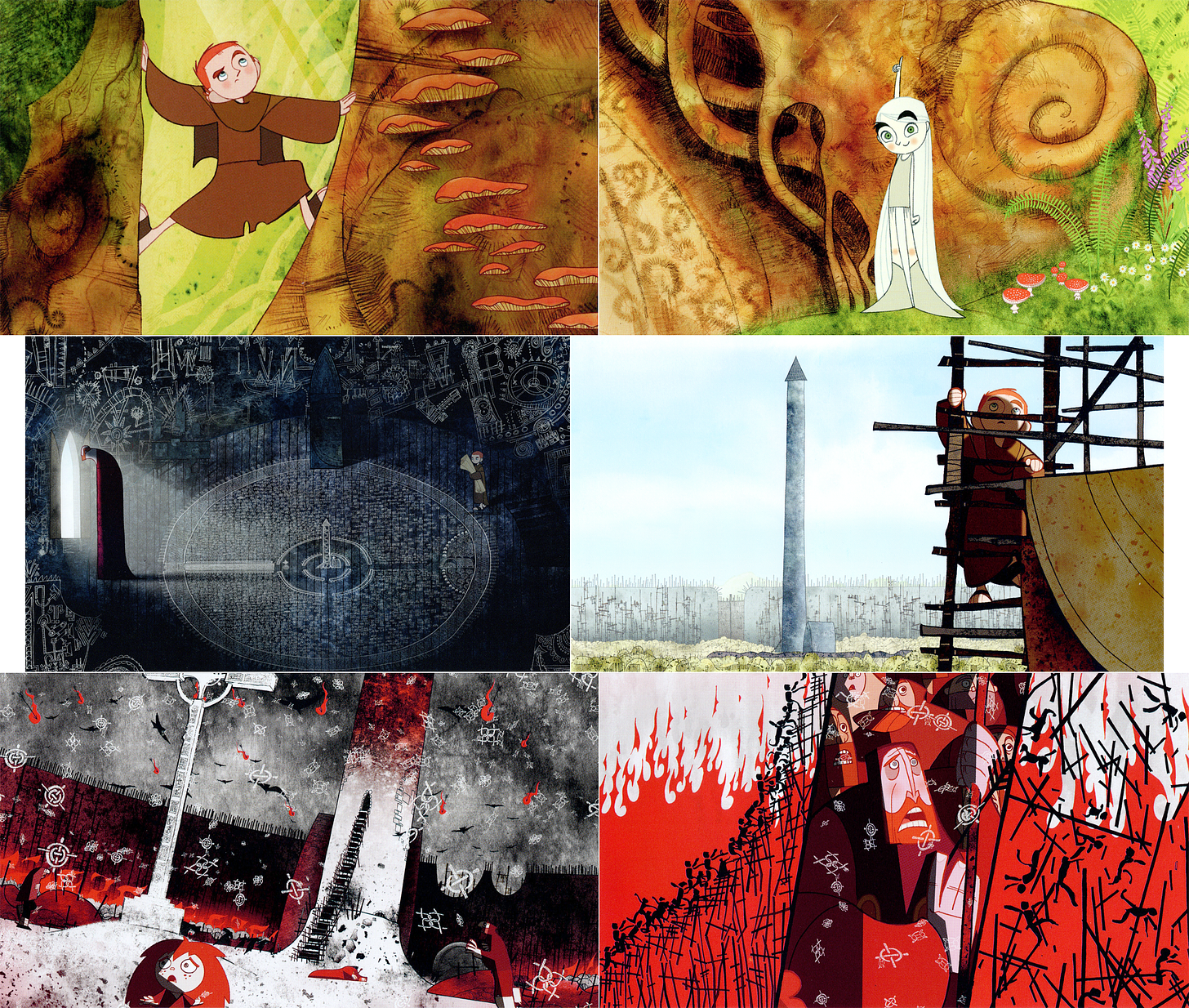

In European animation, there’s no underdog story more inspiring than that of Cartoon Saloon. The upstart studio in Kilkenny, an Irish city of around 26,000 people, has clawed its way up from obscurity to global acclaim since it started in the ‘90s. Its film Wolfwalkers was a hotly tipped Oscar contender this year.

Cartoon Saloon’s ascent was far from a sure thing, though. None of it would’ve happened without the surprise success of its debut feature — The Secret of Kells, released in 2009. And that film barely made it. In fact, it was a labor of love that took over a decade to craft.

“Kells was our first project and represented many firsts for everyone involved,” wrote producer Paul Young in the book Designing the Secret of Kells. The team had essentially no idea what it was doing. According to Young:

In some ways our naivety was a good thing; if we had known the challenges we had to face, we may have listened to the negative advice and not continued. But being very optimistic, we ignored those who said we were nuts and favored those who gave us the good leads.

According to Nora Twomey, the co-director of Kells, sketchy ideas for the film existed by the mid-1990s. They came primarily from Tomm Moore, a young student at Dublin’s Ballyfermot College. He was studying animation in a course set up by Don Bluth.

Moore and his friends wanted to make a film that animated ancient Celtic art — like The Thief and the Cobbler had done for Persia and Hungarian Folk Tales for Hungary. “That’s when we started looking at the Book of Kells and how that had really inspired Irish art and calligraphy and manuscripts,” Moore said last year. He co-developed a story idea with his childhood friend and fellow student Aidan Harte.

As Moore and several friends prepared to graduate from Ballyfermot in 1999, Kells got started. It was called Rebel: Turning Darkness Into Light then, and it was wildly different in look and plot. They founded Cartoon Saloon to continue the film after graduation.

The team used a government grant to set up shop in Kilkenny — in a space lent to them by a local program for young filmmakers. Rebel’s concept trailer followed in 2000:

Moore, Twomey, character designer Barry Reynolds and more animated the trailer. Cartoon Saloon was a small studio with around a dozen members — as Rebel progressed, they spent their first year making “about six Flash e-cards a week” to pay the bills, before moving up to advertising. Somehow, they got Brendan Gleeson to narrate the trailer.

These were the early days. The studio was still known as The Cartoon Saloon — and Rebel was, according to the old company website, supposed to be a “50-minute animated television special.” As Moore later said:1

We were learning everything: how to run a company, how to run a studio, how to work with other artists. We were all a group of peers at the beginning, and we had to learn about the hierarchy that was necessary and the sacrifices that were going to be necessary. It had ups and downs, of course.

Cartoon Saloon struggled to figure out how to make a project as ambitious as Rebel. Eventually, they received a tip from a veteran of Don Bluth’s Dublin studio. “He said ‘go pitch it at Cartoon Movie,’ which we did,” Paul Young remembered.

Cartoon Movie is a pitching forum for animated features, where companies and backers make the deals that keep the industry running. In March 2001, Cartoon Saloon took its trailer to Berlin for the event, and had a serendipitous meeting along the way.

“On the bus to this event from the airport,” Young wrote, “I overheard [producer] Didier Brunner sitting in front of me saying they need[ed] help with extra animation on a certain film with lots of bicycles.”

That film was The Triplets of Belleville, and Young took the opportunity to introduce himself and recommend Cartoon Saloon for the job. He also invited Brunner to the Rebel pitch. “As it happened, it was perfect timing,” Moore later said. “Didier was looking for the follow-up project to the Triplets, and so he kind of came on board then and he started to really show us the ropes of how European co-productions worked.”

Then came the hard part. They had to make an animated feature film — with relatively little experience. It had to be great, which meant developing the script and style far beyond what they’d managed so far. And, most importantly, Cartoon Saloon had to raise enough money to pay for this dream project.

Shake-ups came quickly. Aidan Harte left the Rebel project. A new screenwriter, hired by Brunner, helped the team shape their ideas into a real film. Cartoon Saloon still didn’t quite know how to make one — many of these artists weren’t yet storytellers.

“You know, at Pixar, they talk about story, story, story,” Moore said. “We were really about art direction, animation, art direction, animation. And I had to learn that story was most important the hard way.”

It took years. In the meantime, they were revamping the visual style under art director Ross Stewart. The character designs proved to be a sticking point. “Brunner felt strongly that we move away from any typical ‘classical animation’ influences in the characters and explore a more stylized approach,” Moore wrote.

The goal was to get the look as close to the Book of Kells as possible, without stiffening up the cast. Samurai Jack was a major influence, plus Hungarian Folk Tales and The Thief and the Cobbler. To immerse the characters in the abstract, perspective-free style of the Book, the team broke most of the rules of cel animation. Moore again:

We used tangents and angles and shapes that are usually frowned on in 2D animation to keep the characters simple, but retain a medieval feel. We also looked at old stained glass, because the figures in the manuscript are stiff and icon-like and we needed more freedom.

The style and story developed gradually. Protagonist Brendan required several hundred design passes before he settled into the character we know. The forest sprite Aisling only joined the cast around 2002 — Moore recalled “notes, particularly from Didier Brunner, that the story lacked a female character.” She was based on Moore’s younger sister, and the team used her to represent the matriarchal soul of ancient Irish paganism.

As Cartoon Saloon developed Rebel, it continued to subsist on commercials and other gig work — but it branched out as well. Nora Twomey, who was older and more experienced than much of the crew, moved up to directing short films. She made the Oscar shortlist with From Darkness (2002). Aidan Harte developed the TV series Skunk Fu, which became Cartoon Saloon’s first big break.

By 2004, Rebel had a new name: Brendan and the Secret of Kells. Cartoon Saloon was a long way from where it began — but still in pre-production.

Even after Brunner and Cartoon Saloon linked up in 2001, it took years for Kells to find enough backing to enter full production. “By the time the budget had been gathered together,” Twomey wrote, “there was so much preliminary design work done that at times I feared it would stifle the characters’ performances.”

The money to make Kells was “raised from almost every source imaginable,” Moore said.2 With Brunner’s help, the team built a network of 32 backers in three countries. Paul Young explained that funding came from “grants, loans, sales advances, distribution advances and film tax shelter schemes.” To access them all, Cartoon Saloon delegated work on Kells to studios across Europe that could apply for their own, local support.

“It’s the nature of European co-productions that things have to be broken up between all the different countries that are involved in the funding,” Moore said. In the end, they raised around €5.35 million.

When production kicked off in 2005, Twomey joined Kells as a co-director. Moore leaned on her experience, noting that her “skill set was much more rounded” than his own, with a greater emphasis on filmmaking over visuals. She was key to the voice sessions as well — where Brendan Gleeson returned, this time as the Abbot.

Over 200 artists would contribute to Kells during its long production. Cartoon Saloon numbered around 40 people. As Moore said, “We did about 15 minutes of sample animation, designs, all of the key posing and most of the backgrounds.” Other work was split between Belgium, France, Brazil and the Hungarian studio behind Hungarian Folk Tales.

To keep Kells focused, even as the broad division of labor threatened to muddy the vision, Cartoon Saloon relied on what it dubbed “scene illustrations.” Made during the storyboarding stage, these were 200 or 300 mockup screenshots drawn over finished backgrounds.

Moore called them “blueprints” — at every stage of production, the teams worked to replicate each shot, so that the film wouldn’t slip away.3

Production proved to be brutal. The animation process for Kells lasted roughly two years, wrapping in 2007. It took another two years to finalize the film. Moore recalled:

… it was such a difficult production and such a challenge for the studio that there were a number of moments where we were afraid that the film wouldn’t get finished. In the end, we even went over budget and had to borrow from friends and family just to get it done. So, there was an enormous sense of completion that I hadn’t wasted my twenties. I was turning 30. I had finished this huge project. But, on the other hand, I’d learned so much at every stage that it was quite painful.

By the time of the film’s launch in 2009, it had changed names again. Although it was still Brendan in France, its English title was now The Secret of Kells. And it was a smash with critics around the world.

The box office didn’t follow — particularly in Ireland, the film flopped. Things were only getting worse. “The studio was hit by the late 2000s financial crisis and, with nothing in development, was at risk of going under,” wrote Carlos Aguilar for The New York Times.

But awards started to come in, including nominations at the Annies. Finally, there was the Oscar nomination. Cartoon Saloon was as surprised as the rest of the world to see Kells on the list. Its distributor in the United States, GKIDS, had waged a low-profile, grassroots campaign to get the film nominated. The company was young — Kells was among the very first films it distributed.

“If it wasn’t for GKIDS picking it up, we would never have gotten the Oscar nomination,” Moore later said. He credited the nomination with keeping Cartoon Saloon together.

Afterward, Cartoon Saloon considered joining the big leagues in Hollywood for its next film. Time and again, the luminaries of American animation advised the team to stay the course. “They would always say, ‘You’re living the dream,’ ” Moore recalled. His conversation with Brenda Chapman (Brave) was especially persuasive.

Moore came away from it all with a realization. “There’s no point trying to make a personal independent project into a big studio project, because you’ll only have your heart broken,” he said. Cartoon Saloon decided to make its next film, Song of the Sea, with the same independent spirit that had powered The Secret of Kells.

But that’s another story.

Today’s issue would not exist without the support of our members. With their help, we ordered the artbook Designing the Secret of Kells directly from Cartoon Saloon in Ireland — one of our most important sources for the article. Thank you all!

Membership nets you our weekly Thursday issues, where we dive even deeper into animation. Until December 25, our founding member tier is $40 off — giving you two annual memberships for almost the price of one. We offer a student discount as well.

2. News around the world

The Animation Guild pushes for more

The fight continues for better wages and working conditions in American animation. Negotiations between The Animation Guild and the AMPTP, which represents the film and television industry, have grown fierce enough that they’ll be going into next year. They were supposed to end on December 2.

For Cartoon Brew, Alex Dudok de Wit has written a helpful explainer about the battle. We don’t know exactly what The Animation Guild is demanding behind the scenes, but it’s dropped hints. One of the main points of contention is Sideletter N, which covers the Guild’s relationship to so-called “new media.”

New media, which includes streaming, is now established media. It’s where the money is made, but Sideletter N doesn’t reflect that. Its conditions remain “less favorable to workers — reduced minimums, less holiday, etc. — as they were agreed back when streaming was a far smaller, riskier business,” de Wit writes.

Alongside the Guild’s previous #PayAnimationWriters hashtag, which successfully spread awareness of what’s at stake, members have rolled out #NewDeal4Animation on social media. Using that hashtag, Owl House creator Dana Terrace recently tweeted, “We’re burnt out! We’re exhausted! And I don’t know a single person in animation, no matter their position, who doesn’t feel guilty for taking breaks.”

Best of the rest

On November 30, the iconic Russian animator Andrei Khrzhanovsky turned 82. His latest film, The Nose or the Conspiracy of Mavericks, has grabbed awards worldwide.

In Britain, Aardman just premiered its new preschool series The Very Small Creatures, which looks adorable. It’s on Sky Kids. Plus, a new Shaun the Sheep Christmas special is out on Netflix.

American legends Ron Clements and John Musker (Moana, The Little Mermaid) have moved to Warner Animation to make The Metal Men, an animated feature based on DC’s comic series.

The company behind Pocoyo, based in Spain, has purchased the animation team KOYI Talent — based in the Canary Islands.

Pearl Studio, also known as Oriental DreamWorks, is making three new films in China. It’s running a new program to find and develop talent, too.

The Chinese company Team Joy, founded in Tokyo during 2019, just received a major round of funding from Japanese companies like TV Tokyo and Good Smile. It previously helped to distribute the hit Legend of Hei in Japan.

In Hong Kong, a 2005 episode of The Simpsons that addresses Mao Zedong’s reign and the Tiananmen Square massacre is suspiciously absent from Disney+.

Mary Apick, an important figure in Iranian cinema, has made her great-looking animated short The Cat available online. It’s a protest piece for women and girls in her country.

According to a report we’ve just learned about, Russia’s Soyuzmultfilm is leaning into the strategy of international co-production, particularly with America, Europe and Southeast Asia.

Lastly, there’s that new Spider-Verse trailer.

3. Last word

And that’s the end! As always, thank you for reading. We’ll be returning next Sunday — but members can catch us on Thursday, too.

Our latest Thursday issue, The Rebel of Soviet Cartoons, takes a deep look at the early career of animator Priit Pärn. He was among the most subversive artists in Soviet animation, battling the censors every step of the way. In the end, his influence would stretch across the world — even reaching the Rugrats team in America.

One last thing. On Twitter this week, we shared the proof-of-concept teaser for Giacomo’s Secret, an unreleased feature film by Sergio Pablos. Way before Klaus, he spent a large part of the 2000s trying to get this project off the ground. Every piece of art and animation we’ve seen from Giacomo has been gorgeous, and folks on Twitter felt the same about this teaser. We read plenty of calls for the project to be revived.

On that note, we’ll end off with a few words from artist Borja Montoro, who helped Pablos on Giacomo’s Secret:

In 2002 we were told Disney was going to leave Paris. At the same time, my good friend and former Disney supervising animator Sergio Pablos called me and asked me if I was interested in coming back to Madrid to work on his new project Giacomo’s Secret.

I was, indeed. We worked together on the script, visual development and character design of that movie for about a year. And just the two of us animated the whole movie’s trailer. It was the first time someone seriously […] gave me the chance to do design for a feature. Something that I’d always wanted to do but never came out before. Since then, I have split my career. I keep working as an animator when there’s 2D stuff to do. Same with character design. I have been with SPA Studios ever since.

See you again soon!

From Tomm Moore’s interview in the book On Animation: The Director's Perspective, an important source for the article.

From the creators’ commentary track to The Secret of Kells, also referenced several times.

From the “Director’s Presentation” special feature on the Secret of Kells DVD, another key resource.

I remember visiting one of the animation studios, and on the wall were drawings from frustrated animators making fun of how hard the Secret Of Kells style was to animate. I also remember the storyboard animatic being about 15 minutes longer, but they cut a large portion of the film during production to meet the budget.

"In some ways our naivety was a good thing; if we had known the challenges we had to face, we may have listened to the negative advice and not continued."

This has been a very important thing in my life as well!

Speaking of underfunded, struggling animators, allow me to bring to your attention the work of Bakarmax Studios in India, a small company doing wonders! - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqKsMcswGdo