Welcome! It’s a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and our plan goes like this:

1️⃣ The rich spirit of It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown.

2️⃣ Animation news across the globe.

3️⃣ [MEMBERS] Reading Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation.

For new people — it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. You’ll get them in your inbox every week:

Now, let’s get going!

1. Genius on a budget

In the talk around animation today, there’s a strong association between budget and quality. At times, it gets so strong that the word “budget” becomes a synonym for quality itself.

Take Kotaku’s recent review of Chainsaw Man — which notes that “most anime usually don’t feel their budget kick in until around the 20th episode.” This isn’t about the realities of anime production (money tends to go down, not up). Instead, it’s a response to the way that certain anime series look more ambitious toward the end.

The thing is, boiling animation down to its budget isn’t an exact science. Back in the early ‘60s, The Flintstones was the most expensive half-hour series on TV — beating even live-action shows. In today’s money, one episode cost over $650,000, more than double the price of a typical anime episode in 2017.1 The crew got paid fairly (something up in the air at Chainsaw Man’s studio), but that didn’t equate to flash.

On the other hand, a talented, well-managed crew can sometimes turn even a low budget into an immortal classic. One example? Director Bill Melendez and his team on It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (1966).

The Great Pumpkin was the third Peanuts special. The first one, A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965), had been a runaway hit — attracting rave reviews and a 46.6% share of American TV viewers. So, CBS ordered a second one. The follow-up Charlie Brown’s All-Stars! drew a 46.1% share. Another success.

But CBS wasn’t satisfied. Lee Mendelson, the producer of the Peanuts specials, recalled a fateful meeting with unnamed executives from the network. They wanted “another holiday blockbuster” — and the continued partnership between Peanuts and CBS was on the line.2

Mendelson, Bill Melendez and Charles Schulz met to brainstorm this new special, as they always did. The idea arose to try a Halloween show, using a major subplot from the Peanuts comics — Linus’s annual wait for the Great Pumpkin. Schulz considered it “maybe the most original of [his] ideas” from the strip. Snoopy’s feud with the Red Baron went into the mix, too, for the first time in a Peanuts special.

By this point, Melendez and Schulz had been doing Peanuts animation for years — two specials, a documentary and countless commercials. Melendez and his team had even weathered the short schedule and disastrously low budget of A Charlie Brown Christmas. They knew how to animate Peanuts.

And they knew that CBS wasn’t going to give them more money. A Charlie Brown Christmas had a budget of $76,000, a bit more than an early Flintstones episode. Yet TV specials cost a lot more than series. Flintstones could reuse things and strip back its stories. Bill Melendez Productions had to create a much more ambitious show from scratch — complete with songs, unique animation and numerous characters and locations.

Christmas went badly overbudget, and the team felt that its art quality was below par.

Money problems continued on The Great Pumpkin — but, by this point, the team was adapting. “I did [the special] under great duress,” Melendez recalled. “I still had that $76,000 budget, but I knew how to pace myself to keep it cheaper.”

A Charlie Brown Christmas is wonderfully rough-around-the-edges, but the flaws caused by its messy production always bothered Melendez. The Great Pumpkin was something else: something like low-budget perfection. As Melendez said:

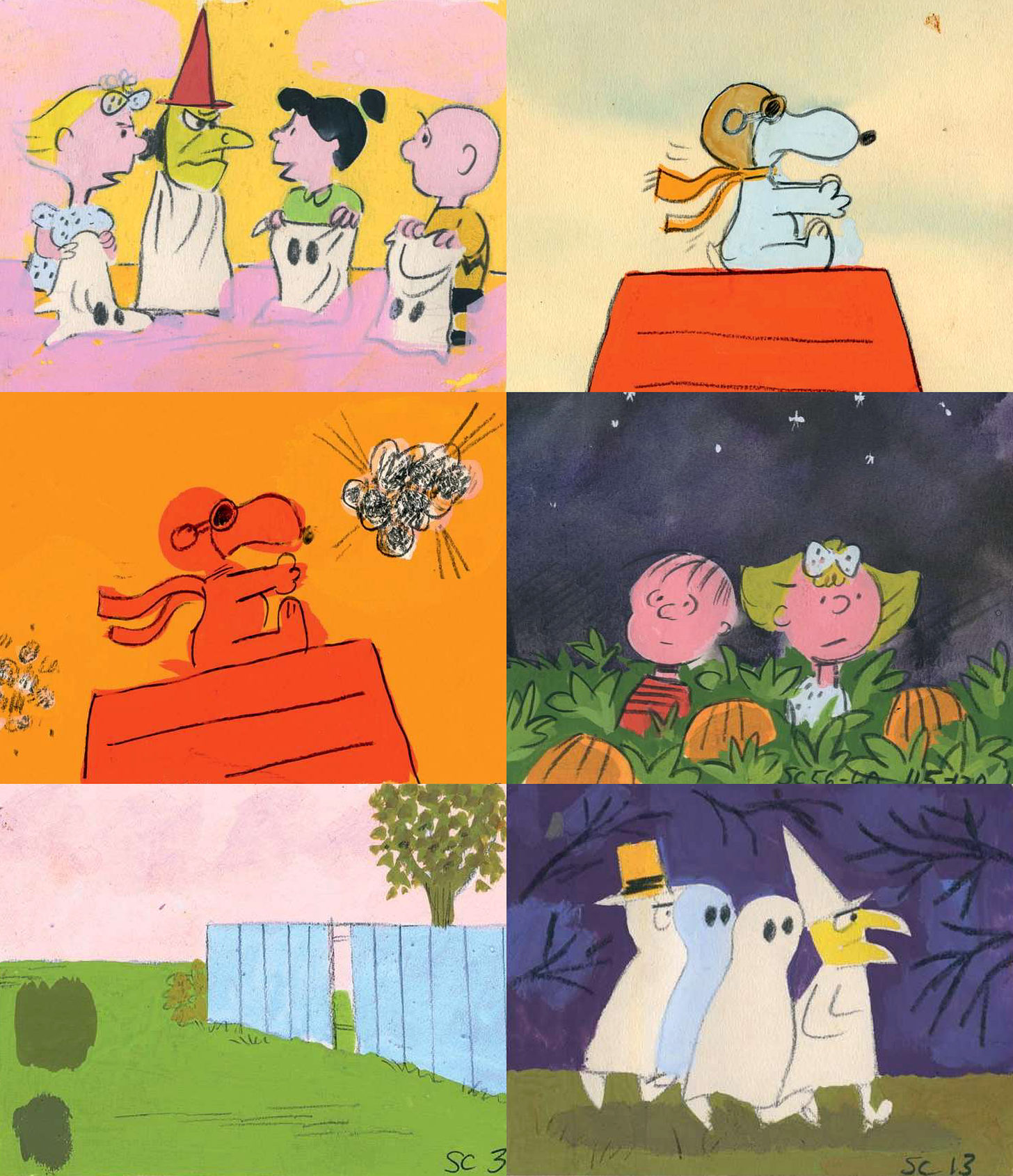

The story was real good. The color was super. Our background artist just went completely out of his gourd in doing a good job. Oh, boy, the color on that picture, we’ve never approached it. And so, when it finished, I really was happy with that thing.

Lee Mendelson had similarly nice things to say. “The Great Pumpkin set the standard,” he argued. “The color was unbelievable. The animation got better right away.”

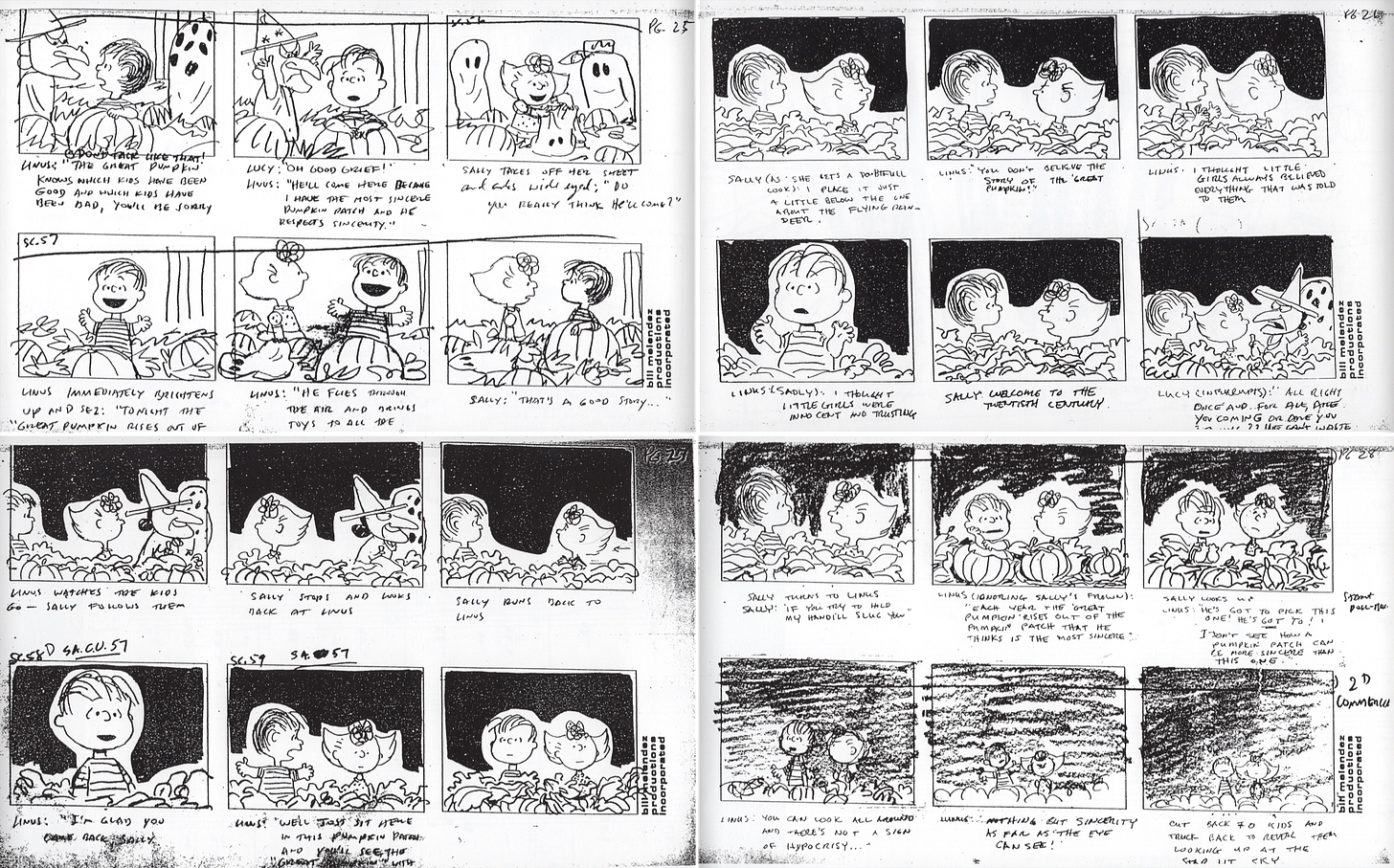

The key players were all in place. There was Schulz with his iconic script — from “I got a rock” to Sally’s tirade in the pumpkin patch. Melendez, a brilliantly understated director, worked on the storyboards and even animated certain scenes.

Vince Guaraldi, the composer for Christmas, was back. He did 20 new pieces for The Great Pumpkin and made important choices for its score— like reviving the track Linus and Lucy, and keeping certain sections (Snoopy’s dogfight, Sally’s rant) music-free. That doesn’t even mention the voice cast, who mostly returned from Christmas and All-Stars, at least as good as ever.

There was a world-class animation staff, too. Frank Smith from UPA was assigned the opening sequence where Lucy and Linus harvest a pumpkin. Melendez called animator Bill Littlejohn “a key to the success of the Red Baron sequence” (he also did Charlie Brown’s “happy dance” toward the start). The sequence where Lucy yanks the football is credited to veteran Rudy Zamora. Melendez recalled of that moment:

… at first, we didn’t know how to handle that. It was simpler to do it in the strip. But in animation, we had to be careful how we had [Charlie Brown] crash onto the ground, so it wasn’t too painful for the TV viewers.

And then there was Dean Spille, the driving force behind the background paintings. “With all the great color of the fall season and the pumpkin patch, we were able to go to watercolors for the first time,” Melendez said. Spille rose to the challenge.

The evocative paintings in The Great Pumpkin fill out the frame, helping to make the whole thing feel rich despite its low cost. “Bill and Sparky [Schulz] were great about allowing me to do anything in terms of colorful skies and clouds and so forth,” Spille remembered. “And it seemed to work.”

The Great Pumpkin is limited animation at its best — using so little to do so much. Scenes come across as full even when there’s an absolute minimum of drawings. It testifies to the strength of each component. The dogfight sequence, especially, is a case study in using color, sound and a handful of gestures to make the viewer feel like they’re watching something much grander than they really are.

Thanks to the efficiency of The Great Pumpkin, it has a tightness and crispness that A Charlie Brown Christmas doesn’t. That one thrives on its technical bumps — they only improve it. The Great Pumpkin, though, is Peanuts polished. It’s hard to find a fault in it.

Not that Melendez didn’t try. To make this project economical, he cut corners whenever and wherever possible, without sabotaging the art quality. Small workarounds that bugged him a little, as he said:

I cheated a lot of things. ... For example, they walk around on sixes. But I [usually] make a point of having them never walk around in unison. I always have them walk a little bit off-beat, so it just loosens it up. But, in this show, I just tried to get away with it. And also I animated a lot of things that should have been animated “on ones” — one drawing for each frame — I animated “on twos.” And I got away with it, I think. Except to me I didn’t. But those are just technical things that are not really important. The picture throughout is very satisfying.

It didn’t just satisfy the team, either. The Great Pumpkin got an incredible 49% share of viewers upon its premiere. When its reruns stopped for a bit in the ‘70s, people were upset.

“We took Pumpkin off the air three years ago, after its sixth broadcast, to make room in the schedule for some of our new Peanuts shows,” Mendelson said in 1974. “But I was repeatedly asked, in person and through the mail, why we had done this. Pumpkin seemed to be a special favorite.”

This half hour of cheaply produced animation is so rich that, even today, the love persists. Even its own team, the group of people most critical of A Charlie Brown Christmas, continued to adore it. “I believe It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown is Bill Melendez’s animation masterpiece,” Mendelson told The Washington Post in 2016.

In a weird way, the cheapness of this special wasn’t just a limitation — it benefited the project, Melendez felt. That went for early Peanuts cartoons as a whole. They developed a low-budget ethos that focused the team. Limitation gave form. As he said:

One thing that helped us in a negative fashion was the terrible budgets. We were forced to do the best we could within those dumb budgets. Had we started from the very beginning using computers and trying to animate these characters as close to real-life animation as possible, it would have been a disaster.

2. Newsbits

It was a big week for animation news — leading to our longest newsbits section ever. A few stories from America drew most of the attention, plus an outsize amount of controversy we won’t wade into here.

Still, it’s important to remember that animation is a large, wide world. The US matters, but it’s one country. This gets clearer to us the longer we study international news. Human stories are playing out everywhere — in Hollywood, but also far outside it.

With that in mind, we bring you the global events of the week, from America to Taiwan to France to Cuba:

We lost Blue Sky Studios co-founder Eugene Troubetzkoy (91) and Angela Lansbury (96), the voice of Mrs. Potts in Beauty and the Beast.

In France, the much-anticipated Gobelins graduation film season begins. Catsuka has already shared the short Last Summer.

Speaking of Gobelins, it’s partnering with Mounia Aram of Morocco “to promote and develop pan-African animation.” (Aram said at a recent event in Rome that animation made in Africa is “at the beginning of something really huge.”)

Another from Catsuka — a French music video with an animation style unlike any we’ve seen before.

A project made by students and teachers, Shine On Us (Taiwan/China), just won an award at the Chuncheon Film Festival in Korea. See the film on YouTube.

In America, Warner Bros. Television shed 26% of its workforce. Variety reports that the “development and main production teams” at Cartoon Network Studios and Warner Bros. Animation will now fold together — the latest move by David Zaslav to centralize the relatively independent divisions inside Warner.

No fan of the American studio UPA should miss this groundbreaking post by Cartoon Research about a lost film and The Boing-Boing Show. (Thanks to Toadette for the tip!)

Also in America, Craig McCracken, Lauren Faust and Rob Renzetti say that they’ve begun developing the new Powerpuff Girls series. McCracken notes that it still isn’t greenlit: “We have a very long way to go.”

A Chinese article that interested us: an analysis of which studios made the 161 animated projects released by iQIYI, Youku and Tencent Video this year.

One more from France — an interview with the directors of Little Nicholas: Happy as Can Be, which won the Cristal for features at Annecy 2022. The article has a pretty four-minute excerpt, too.

In Japan, Studio Ghibli is reprinting “every original poster and pamphlet for all 23 of its feature films,” per Anime News Network. They’ll be sold online, at the Ghibli Museum and at the Ghibli Park — which is opening November 1.

A Cuban animated series, Watercolors of Cuba, is being broadcast by Cubavisión on TV (and YouTube). According to the news site Radix, the show pays tribute to the late Afro-Cuban poet and musician Luis Carbonell.

In Russia, the September box office was down 70% compared to 2021, and the state continues to discuss legalizing unlicensed foreign films as a solution. One politician warned theaters that they’ll fail otherwise — another went so far as to suggest nationalizing piracy outright. The blowback from Russian companies has remained fierce. Film distributor Vadim Ivanov asks Russia “not to succumb to a momentary desire” that “kills the long-term prospects of our market.”

Lastly, we took a deep dive into a scene by animation legend Art Babbitt — reportedly his favorite work of his whole career.

3. Essential books — Cartoons

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.