Animating 'A Charlie Brown Christmas'

Plus: global animation news, 'Barber Westchester' and more.

Welcome! We’re here with another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And these are our topics today:

One — a look inside the animation of A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Two — animation news from around the world.

Three — highlighting Barber Westchester and The Summit of the Gods.

Four — the last word.

Have you signed up to receive new issues in your inbox each week? It only takes a second:

That’s out of the way — let’s go!

1. “I think we've ruined Charlie Brown”

A Charlie Brown Christmas deserves its reputation. It’s not just a great Christmas special — it’s the greatest Christmas special. The show is tender, funny and meaningful in all the right ways. Although it first aired in 1965, the whole thing feels timeless.

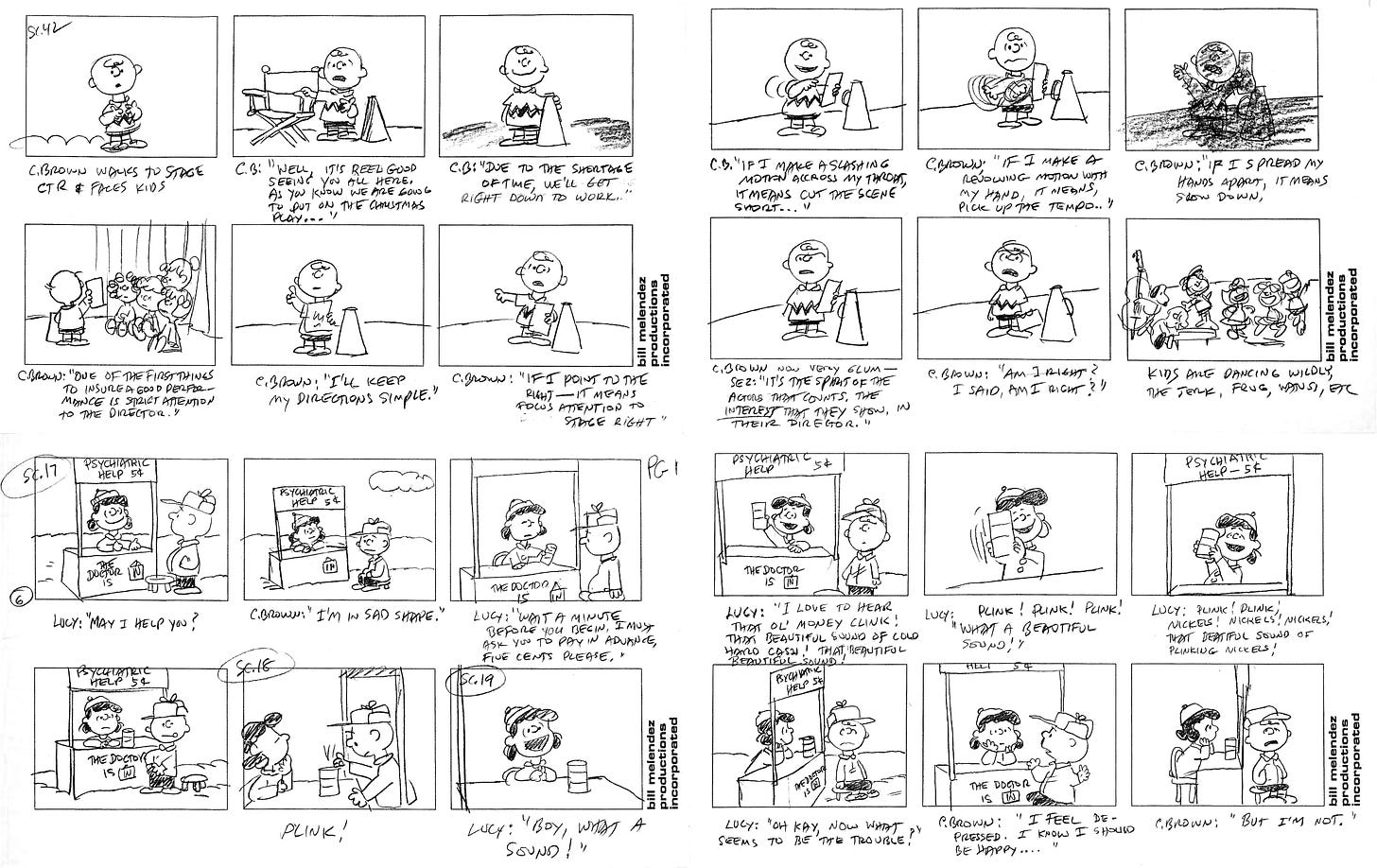

We’re all so close to A Charlie Brown Christmas, though, that it’s easy to miss its qualities as a work of animation. It didn’t appear out of thin air, fully formed — the magic was crafted by human hands. Seeing Charles Schulz’s characters in motion may feel natural now, but figuring out how to animate them was a challenge that the team almost didn’t overcome.

“When we saw the finished show,” recalled director Bill Melendez, “we thought we had killed it.”1

Bill Littlejohn, an animator on the special, once said, “The Peanuts characters were not designed for animation.” Schulz hadn’t broken them down into easy-to-draw shapes. They were idiosyncratic designs, unique to him. Animator Dale Baer, a Disney legend from projects like The Lion King, put it like this:

We sit here and draw Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck and characters like that with no problem, but to draw Schulz’s characters took a talent unto itself. Many people wouldn’t say that, but just let them sit down and try to draw those guys, and they’ll find out. You feel like you can’t draw worth a darn when you work on those characters.

There was another problem, too. A Charlie Brown Christmas was animated in four months, and was allotted a tiny budget of $76,000 (around $660,000 today). The budget was so small that the team went $20,000 over that amount — and still had less than half the money of the first animated Christmas special, Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, from 1962.

The quest to animate Peanuts properly had started several years before. Bill Melendez, born José Cuauhtémoc Melendez, was the main force behind it.

Schulz first allowed Peanuts to be animated in promotions for Ford, starting around 1960. Melendez directed these, too. His designer Sterling Sturtevant, known as “the most prolific female character designer” of her era and hailed for “setting the commercial standard for the times,” worked alongside Schulz to figure out the look.

That early Peanuts animation (like this piece animated by Bobe Cannon and co-designed by Sturtevant) made key discoveries about how to move Schulz’s characters. The artists leaned on their past work at UPA, and on the limited animation techniques they’d pioneered there. Melendez, a top UPA animator, recalled some of his earliest attempts to make Peanuts animation click:

A normal human being might walk fast on twelve frames, and normally at about sixteen frames for each footfall. But if you have these characters walk on sixteens, they’re going to be floating. I made several experiments, and these kids, because of their size, have to walk on sixes: every six frames is a step.

They were getting closer to A Charlie Brown Christmas, but there was still more to learn. Because of the Ford job, Melendez and his team were hired to animate the Peanuts characters for a 1963 documentary about Schulz’s work (see it here). This animation gets even closer to the comic’s look.

By this point, one thing’s clear — the animators had solved turning the characters. This was a problem early on. Bill Littlejohn once noted that Charlie Brown’s head is “a different shape at every angle, with that little glob of hair on his forehead changing completely from front view to profile.” That made him hard to turn. Littlejohn said that they eventually “figured out how to start a turn and then zap to the last position.”

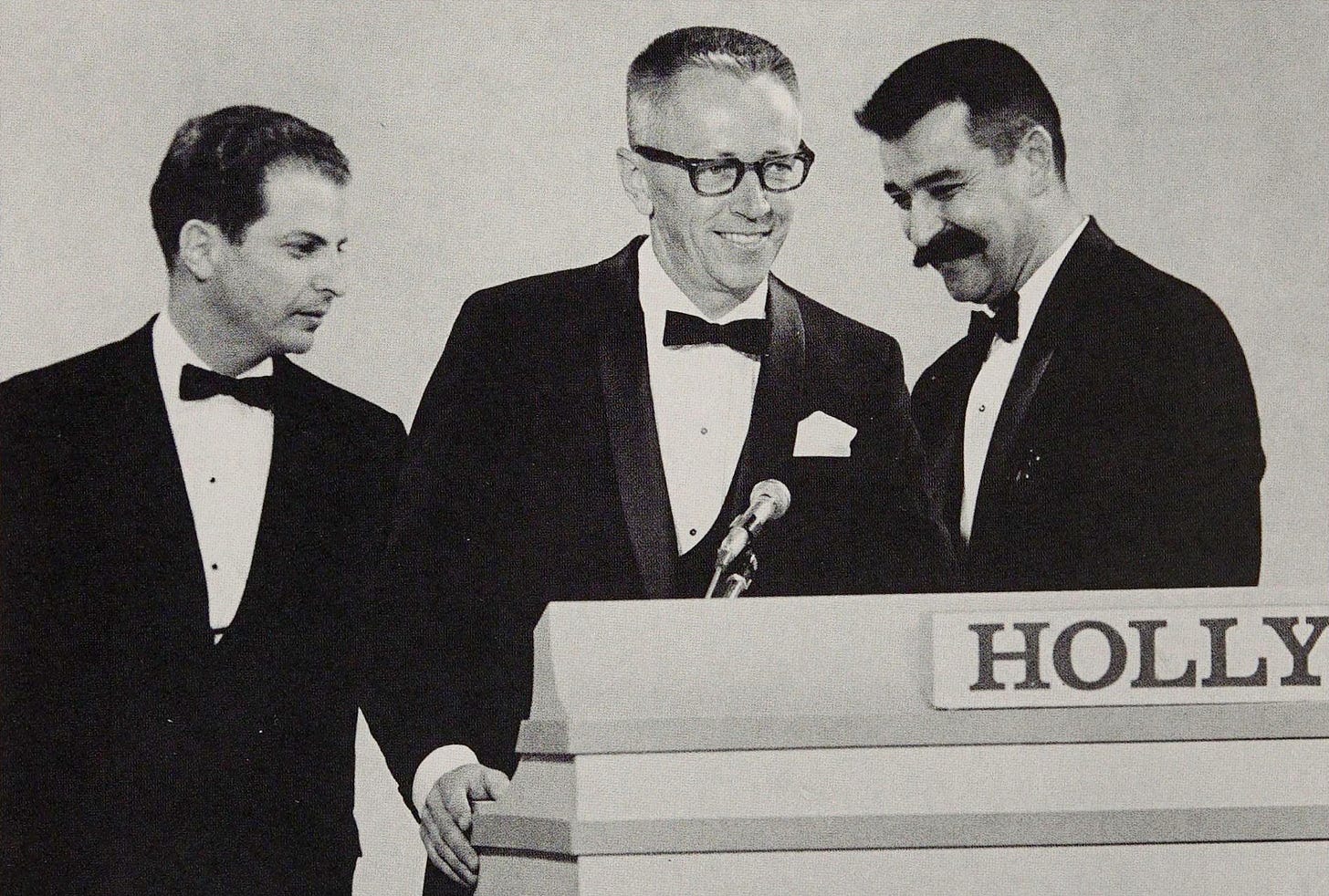

Melendez and Schulz had built a rapport, but none of their work together had led to a full-fledged Peanuts cartoon yet. That opportunity came soon after — when the documentary’s producer, Lee Mendelson, received a call. Coca-Cola wanted to sponsor a Peanuts Christmas special.

“At that time, specials were always one hour,” Melendez recalled. “They wanted me to do a one-hour show in about four months. I said, ‘You can’t do it.’ ”

With CBS signed on as the broadcaster, A Charlie Brown Christmas became a half-hour special. Melendez said that a four-month schedule was “okay” given the length, but the process was still a rush. The thing was that Melendez had never directed a special before — he didn’t even know how to budget one, and he undercharged CBS.

Animated commercials tended to be expensive, and, combined with their length, that let artists put in care and time that standard cartoons didn’t allow. Dropped into the wringer of primetime TV production, Melendez and his team weren’t able to polish their work like before. With designs as tough as Schulz’s, that caused headaches. “It had so many warts and bumps and lumps and things,” Melendez said.

A few major members of the team were Bill Littlejohn and designers Ed Levitt and Ruth Kissane (she played a key role in the iconic dance sequence). Melendez, who voiced Snoopy, reportedly storyboarded the special by himself.

Although they drew from their past experience with Peanuts, the team found that A Charlie Brown Christmas was turning out rougher and more homespun than they’d intended. Melendez was particularly pained by Linus’s famous speech sequence — “such poor animation, such bad drawings,” he said. Lee Mendelson recalled the moment when all seemed lost:

... it was about three weeks before the show was to air, and we had never seen it in its entirety. So Bill and I and maybe ten of his staff watched it. In the closing credits, they had misspelled “Schulz”: they had a “t” in it. They had to redo that right away. Bill turned to me and said, “I think we’ve ruined Charlie Brown.” But Ed Levitt [...] stood up and said, “This show is going to run for a hundred years.” Everybody thought he was nuts.

“I was so unhappy,” Melendez remembered. “All the bad animation, the bad drawings.”

Schulz and CBS didn’t like the special at first, either. (“I thought it was a disaster, because the drawing was so poor,” Schulz later said.) But it aired anyway — it was too late to turn back. A Charlie Brown Christmas premiered on December 9, 1965. And it became a titanic hit with viewers and reviewers alike. It won an Emmy.

In retrospect, it’s pretty clear that Melendez and the team didn’t realize what they had. They were fixated on little things — like how Charlie Brown’s tree “grows several branches between the tree lot and its arrival at the rehearsal site,” which Schulz found agonizing to watch.2

That misses the magic of what’s happening. The artists’ work for A Charlie Brown Christmas has a handmade quality that meshes perfectly with the story, the feeling. Their talent and experience was combined with the rush of production to create something that none of them would’ve made on purpose. Everything they’d learned allowed them to be spontaneous.

There’s a touching innocence to the way A Charlie Brown Christmas looks and moves — the same innocence that Schulz had put into the script. Later in life, Melendez seemed to come around a bit to what he hadn’t seen at the time. “The inconsistencies and little problems seem to make it even more endearing to a lot of people,” he said.

That’s part of it, but it goes deeper. Discussing the speech sequence that Melendez hated so much, the veteran Pixar animator Doug Sweetland said this:

Linus’s speech at the end of A Charlie Brown Christmas still stands out as one of my favorite moments. I’ve used that brilliant, understated acting in animation talks. A lot of times when you’re an animator and you get a scene, you’re trying to figure out “What should I have the character do?” when “What’s the most truthful thing to do?” or “What is all the character needs to do?” may be better questions.

2. News around the world

Epic MegaGrants and animation

This week, Epic Games shared figures about its MegaGrants program — a $100 million venture to fund game, animation and other projects. The company reported on its blog:

… since its launch in 2019, Epic MegaGrants has now supported more than 1,600 creators and teams across 89 countries, with nearly 400 new recipients benefiting from the program this year alone.

Only some of those recipients are animators, but the numbers are worth paying attention to. Grants are a standard part of the animation ecosystem in Europe, but, in America, most production is based in California and made for big companies. Grant programs exist, but ones at the size of Epic MegaGrants, which offers up to $500,000, are rare to find.

And Epic has clarified that this is a grant — “you will continue to own your IP and will be free to publish however you wish,” it’s explained. At a time when so few animators own their work, it’s encouraging.

We’re already seeing the early results. Chromosphere funded part of its indie series Yuki 7, released this year, with MegaGrant money. Animators around the world are applying, too. Last week, we reported that Kidscreen had named “real-time animation” a global trend of the year, driven by Epic MegaGrants. DDEG in Canada has received a couple of them, helping it fund projects like Aiko.

It remains to be seen whether this program will have Epic’s intended effect — converting production pipelines en masse to its Unreal Engine technology. But it’s hard to find so much cash with so few strings attached in animation. If Epic keeps up what it’s doing, we might well see an Unreal animation boom.

Best of the rest

We had a few sad passings this week. One was animator Vera Pacheco, a veteran of Disney and Don Bluth Productions. Another was Giannalberto Bendazzi (75), one of the world’s most important animation historians.

The American film The Bad Guys, produced at DreamWorks, drew a lot of attention this week with its trailer.

The upcoming Ghibli theme park in Japan’s Aichi Prefecture now has a logo, designed by producer Toshio Suzuki. It’s set to open in late 2022.

A few months ago, Tangent Animation in Canada laid off its entire staff without warning — or pay. Now, it’s being forced to remedy that.

A notable tidbit from The Japan Times this week. “Aside from a handful of independent licensors, the world of anime publishing in the West is now, for better or worse, in the hands of a few giant corporations.”

Alongside staples like Cartoon Movie and Cartoon Forum, there’s now CartoonNext — a new event in France about “what’s next for the animation industry.”

During the Cartoon Business event in the Canary Islands, three animation veterans laid out “the golden rules for surviving animated co-productions” in Europe.

Japan has only one Oscar-qualifying festival for animated shorts right now — under the unusual name “Short Shorts Film Festival & Asia.” It just broadened its rules to allow for a wider variety of entries.

In Ireland, Cartoon Saloon more than doubled its profits between 2019 and 2020, attributed in part to the production of Nora Twomey’s upcoming My Father’s Dragon.

The Japanese director Makoto Shinkai (Your Name) has announced a new film called Suzume no Tojimari. It’s due in late 2022.

Lastly, Screen Rant looked at the top-rated animated films of the 2010s on Letterboxd — and the work of indie animator Jonni Phillips placed twice. Her latest, Barber Westchester (see below), debuted December 12.

3. Gems of the month

Two feature films grabbed our attention this month. They’re wildly different from each other, and in some ways polar opposites — but both are monumental achievements in what they’re trying to do. The films are The Summit of the Gods and Barber Westchester.

We often read complaints that 2D feature animation is dead, that animated stories are samey and that adult-oriented animation isn’t truly adult — just edgy. If that’s you, then The Summit of the Gods, streaming on Netflix since the end of November, is one of your must-see films this month.

This project hails from France and Luxembourg, but it adapts a Japanese manga series. It’s a story about mountain climbers — and a photojournalist whose search for one of them, a haunted man named Habu Joji, upturns his life. The tension is thick throughout, and at points becomes almost overwhelming.

But director Patrick Imbert (The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales…) doesn’t lose control. He infuses Summit with a rare level of filmmaking — you feel that every shot, every edit, is exactly where it must be to tell the story. Late in the movie, there are long sections without any dialogue, but the pace never wavers. In Summit, Imbert and his team have woven a tale about the drive to do the impossible that stands as one of 2021’s top films.

Barber Westchester is about that drive in another sense. It’s a feature film made nearly all by one person. The project took two years, yet director and animator Jonni Phillips somehow managed it with the help of a few friends — like Ian Worthington (Bigtop Burger). The workload was inhuman. “It literally shouldn’t exist,” Phillips notes, “but it does anyway.”

You could compare the result superficially to Home Movies with horror elements, but that’s not it. Barber Westchester is a 90-minute, no-fi experience — one that finds structure in how intensely personal it is. Even the way Phillips moves the characters is pure expression, breaking away from any realism or rule-following. Barber is less of a movie and more of an energy that invites you to live inside it.

It’s about a would-be astronomer, Barber Westchester, who battles mental illness and a messy family. As the plot unfolds (parrot infestations, clay doppelgängers), Barber has to cope with the discovery that space doesn’t exist. That sounds surreal and funny, and it’s meant to be, but the emotions aren’t played for laughs. The film strikes an odd balance between humor, fear and poignancy — one that’s compulsively watchable.

We’ve never seen anything quite like Barber Westchester. Phillips has tapped into the essence of independent animation — it’s self-defining. No studio in America, no animator besides Phillips herself, could’ve made this. The only place where you can see it right now is her Patreon page, where access costs as little as $2.

Barber, and the beautiful optimism it settles on, has stuck with us since our first watch. For us, it’s one of the most unique and enchanting films this year. We recommend it.

4. Last word

And that’s a wrap! This has been our final Sunday issue of 2021. They’ll be back starting January 2.

We aren’t going into hibernation until 2022, though. Our Thursday issues, for members only, will continue through December. If you’re a member, you can stay tuned for more great animation over the holidays.

To close out, we just want to thank all of you. When we launched this newsletter in February of this year, we had no clue whether anyone would read it. We couldn’t have imagined what was in store. It’s our hope that our newsletter has been as positive for you as your readership has been for us.

Running the Animation Obsessive newsletter has been a crash course in just about everything. We never expected to end 2021 with thousands of readers from all over the globe, but here we are. With your support, we’ve been able to keep making the newsletter better, fuller and more interesting each month. We plan to get even more ambitious in 2022 — and we hope you’ll stick with us for the exciting stuff to come.

See you again soon!

From the book A Charlie Brown Christmas: The Making of a Tradition, an important source for the article. Other sources include The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation, Cartoon Modern, the 1961 Annual of Advertising Art and When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA.

From The Commercial Appeal (December 6, 1995).

Fantastic last Sunday issue, and congratulations on the year's successes! Loved the homage to Charlie Brown, and appreciated the gems of the month, flagged to watch shortly.

I laughed out loud at "*the* greatest Christmas special;" I'm guessing that this is probably an annual tradition for the staff. Surprisingly, while I can immediately recognize a scene from the film, I don't know that I've ever watched it from end to end in a single sitting. Perhaps this is the year to remedy that.

Fascinating to read bout the unique challenges to animating this film, down to the walk cycles and head turns. Yet again I find myself marveling at how hard it is to bring life to moving drawings, but, as your affection for this film attests, and as you so well put it, there's a magic that can happen despite things like flaws in execution. And when it does, the resonance an animation can produce in an audience is outsized. I think that's what's so beautiful about this art form.

Though it seems like you'll continue with member issues through the holidays, hopefully the staff will also find a moment to rest and celebrate.

Great article as always. Even when I was very young I did get an inkling that the production for A Charlie Brown Christmas was probably quite messy, its one of those things that you watch and get that feeling about but the overwhelming amount of heart and compassion that the short demonstrates sort of shoots that feeling to the back of your mind. Its interesting to read how the artists behind the short felt before and after it became a success, it can be hard for an artist to see why people love their work when they themselves just see the mistakes behind it.

Its interesting to see EpicGames make bigger and bigger steps into the art and animation industries. With their buy out of ArtStation and subsequently making most of the learning resources on the site free to their Epic MegaGrants program to fund animation and games while allowing the creators full ownership of the product. Its genuinely really cool to see but a pessimistic side of me feels as if its just a huge corporation just trying to find ways to spend money, its kind of hard to distinguish. Even so Yuki 7 was a huge highlight for me this year and it wouldn't have been made with out the Epic MegaGrants program.

As always great newsletter keep it up!