Happy Sunday! It’s a new issue of Animation Obsessive, with a new batch of animation highlights. Our lineup today goes like this:

1️⃣ How Frédéric Back moved mountains in The Man Who Planted Trees (1987).

2️⃣ The world’s animation newsbits.

New here? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, right in your email inbox. Join 10,000+ other readers from across the globe:

With that, we’re off!

1: A labor out of love

The late Frédéric Back was never a celebrity, but he counted most of the great animation masters among his fans. People like Glen Keane and Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog). Not to mention the stars of Studio Ghibli: Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

Back, who made short films in Canada largely by himself, was too humble to take much credit for his impact. (“I never expect to have any kind of reputation. I just try to make good work,” he explained.) Even so, it’s hard to overstate his influence, especially in Ghibli’s case. Takahata once said, “Frédéric Back is my master, my mentor in life, as well as in my animation work.” He borrowed openly from him.1

Miyazaki, too, is an admirer. He and Takahata discovered Back’s animation together in the early ‘80s. “It was a shock to both of us,” Miyazaki recalled. “As we trudged home after the film, I remember saying to Takahata-san, ‘So, I guess we’re failures, aren’t we…’ ”

A few years after that exchange, Back would release another film. A film even more ambitious and beautiful — the grandest statement of his career. It was The Man Who Planted Trees (1987), one of the highest points ever reached in animation history.

“This is a powerful work,” Miyazaki said after watching it, “that couldn’t have been made halfheartedly.”2

The Man Who Planted Trees is a film so widely praised, for so many years, that it risks the trap of becoming too much of a classic. Which is to say: a work of art so clearly good for you that it starts to feel like an obligation, like studying.

But Back’s 30-minute masterpiece always evades that trap. It stays new and immediate. It meets you where you are, at any age.

If you don’t know the outline, The Man Who Planted Trees is about a Frenchman who stumbles across a shepherd on a barren stretch of land. The shepherd, he learns, is planting trees. They meet a few times over the years as the shepherd continues his quiet work, alone and in secret. Decades pass — and the dead earth is renewed with life, all because of one person’s “constant, magnificent generosity.”

Frédéric Back was a tree-planter himself, in his spare time, and the production of this awe-inspiring film cost him five years of his life. He felt the sacrifice was necessary. “I absolutely had to do this film,” he later said, “because it symbolizes all the good that human beings can accomplish.”3

The story wasn’t his own invention. A French author, Jean Giono, had published it in the 1950s. Giono’s original piece was so evocative and convincing that many readers thought the shepherd character, Elzéard Bouffier, was a real person.

Back was among them. He discovered the story in a 1974 issue of Le Sauvage, a French-language environmentalist journal. Back said that reading it:

… moved me deeply, because it is a lesson of patience and generosity. Giono had put into words everything that I wanted to express in my drawings. […] I sketched a series of images immediately. When I found out that Elzéard Bouffier was in fact a fictitious person, I was disappointed. But then I collected all sorts of articles relating to the humble, generous achievements of people teaching reforestation in India, or recreating a forest on the opencast mines of Africa, or protecting the last virgin rainforest of a South American country, etc.

Back didn’t get to animate The Man Who Planted Trees just yet, though. He simply kept thinking about it. For six or seven years, the film seemed unlikely to happen at all.

Back was around 50 years old when he read Giono’s story — almost Bouffier’s age when he purportedly started planting trees. And Back was a relative newcomer to animation (“very late,” as he put it). He was still learning the ropes.

His career really only started in 1968, when he joined the Montreal animation branch of Radio-Canada, a public broadcaster. He admitted that he “wasn’t so interested in animation” until then — he’d done illustrations, special effects, sets. But producer Hubert Tison hired Back to animate, and began to develop his talent.

“He helped me as a collaborator and was very critical and demanding,” Back remembered, “so it was really a fantastic chance to be involved in animation.”

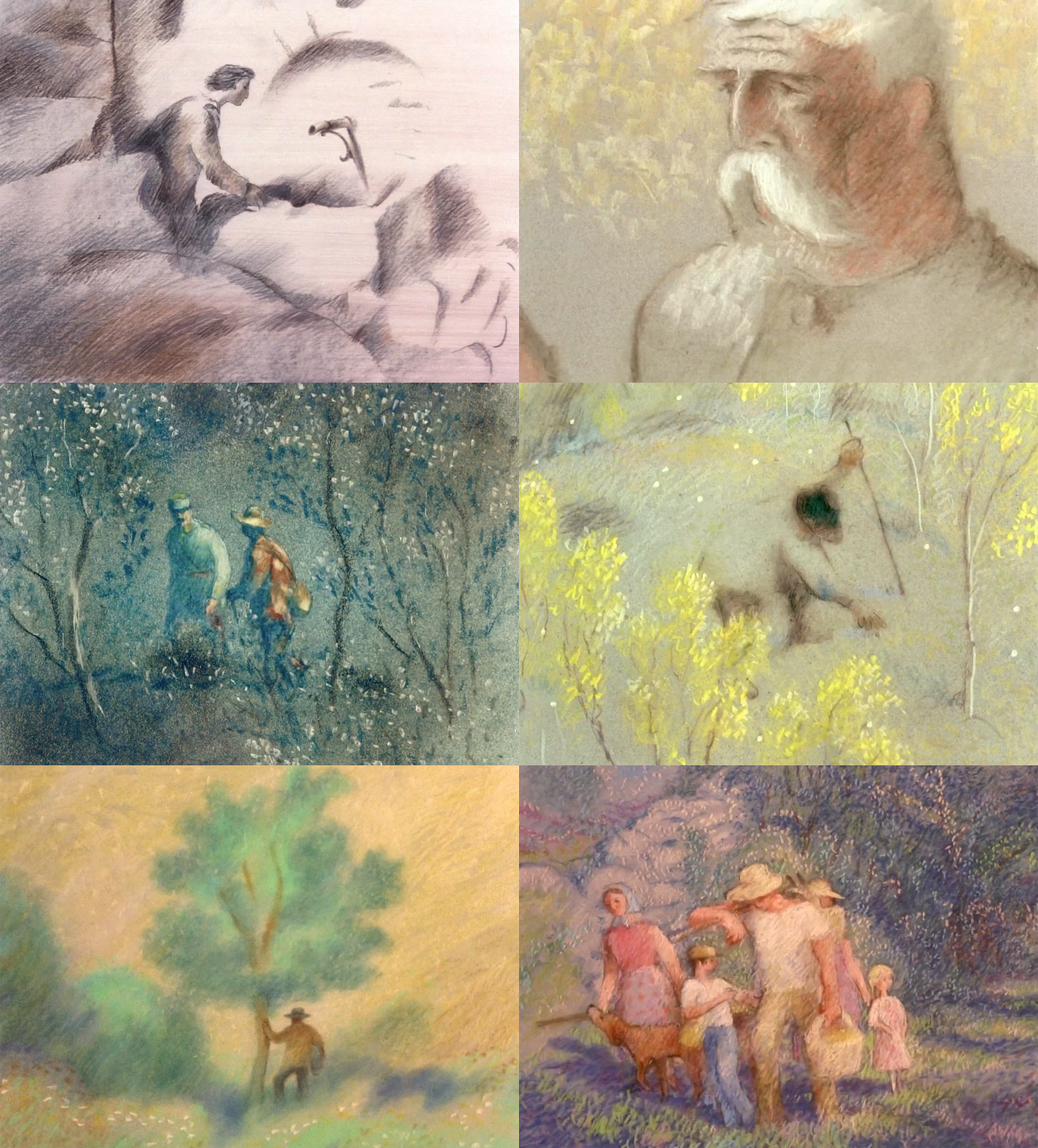

And along Back went, starting with films like Abracadabra (1970) and slowly honing his craft. He came upon his own animation technique, drawing on frosted cels with colored pencils. “I use a type of grease pencil with a wax base,” he noted. The effect is soft and painterly. His work began to get Oscar nominations in the late ‘70s — and then he won for Crac! (1981).

In the background, though, he was still thinking about The Man Who Planted Trees.

Everyone could see that Giono’s story didn’t fit an animated short. “I told him there wouldn’t be any place for animation,” Tison remembered. It was all too slow, too long, too reliant on words, too complete in itself to support visuals. Back didn’t disagree: he later described the story as “quite inappropriate for an animated film treatment.”

Yet he wanted to go ahead with it, telling Tison that “one must do crazy things.” Back believed too much in the story and its message to quit. They ended up proposing the film — only to hit a wall at Radio-Canada. Here’s Back again:

Many people objected to The Man Who Planted Trees because it did not follow the story lines of previously successful animation films. Many people were against it. It took over a year before the project was accepted.

The turning point was that Back’s skill finally became undeniable. The whole world was taking notice. “Eventually, the [1982] Oscar for the film Crac! enabled us to get permission to do The Man Who Planted Trees,” Back said. He credited the greenlight to a higher-up manager, Robert Roy, who fought to get the film made — even though “no project of that kind had ever before been accepted by Radio-Canada.”

The task of animating this story — of doing it justice and keeping the narrative flowing — was historic in scale. Back had grown into one of the medium’s greatest artists before he started the film, but it was almost too much even for him.

In Tison’s words:

Sometimes, during production, Frédéric would tell me, “Giono is putting me through the wringer.” The adaptation to animation was no easy task, as I mentioned. Also, the half-hour length. When one starts on such a long-term project… The film took five years to make. The first year, the end is not even in sight.

And they had a false start. At first, Back tried animating in ink, but the results left both he and Tison unsatisfied. After months of labor, Back visited Tison to say that he’d thrown away everything: all of the finished frames he’d drawn so far. Tison was shocked, but he put his trust in Back’s dedication, and chose to protect the project.

“So I told him to go ahead, but not to tell anybody,” Tison recalled.

Back went back to a more painterly style, with Prismacolor pencil drawings and dry pastel backgrounds. The process required a toxic fixative, which on Crac! had already cost him an eye. But he only upped his ambition this time, planning the new film’s visual progression more carefully than ever. He started with “a low level of color and shape” and slowly added more as the story went on.

Drawing straight onto cels, Back crafted frame after frame at a tiny size. Each one was roughly 3.9 inches by 5.9 inches, so that their textures became visible when blown up during projection. He drew some shots across several layers of cels; others were filmed with extensive double exposures, fading the drawings between each other in a seamless, semi-transparent flow.

The Man Who Planted Trees comprised 20,000 drawings in the end. Back preferred to work alone, but the scale of the job forced him to accept help from an in-between artist, Lina Gagnon. She drew a large chunk of the film: around 3,000 frames, hewing close to the style Back had laid down. He would review her work — applying the fixative when he was by himself, and the only one at risk.

Back remembered Gagnon as “[e]ver patient and painstaking.” She offered a similar recollection in the documentary The Nature of Frédéric Back (2011):

This is a man with an amazing capacity for work. He would draw for at least 60 or 70 hours a week, and then on the weekends he’d plant trees and flowers with his wife Ghylaine. I always wondered if he ever slept.

The truth was, Back was as driven as the tree-planter whose story he was telling — the shepherd who noticed that “the land was dying” and decided to do something. The Man Who Planted Trees (embedded above) may not be loud, but it’s a protest film of incredible intensity.

Even in the 1960s, Back had been an activist in the environmentalist movement, with strong anti-war views. He lived by those beliefs. Almost all of his work circles around humanity’s destruction of the world and itself. The Man Who Planted Trees is punctuated by two World Wars, and is about a landscape ravaged by human evil.

More importantly, it’s about how people can take radical action for good, as Back himself was trying to do. He said:

I tried to communicate my concern and love through my drawings of plants and animals. I tried to make my work as positive as possible, to transmit through image my love of humanity and nature. Against war, against all the aggression of mankind.

Back was ideologically opposed to cheapness in art. He criticized “scenes or drawings that are easy to produce but have a negative consequence.” The only thing that interested him was the hardest thing: “the search for beauty, [which] is very demanding, takes a long time, but has a beneficial effect on people.”

Tison once called Back a “relentless” creator. He worked with never-ending energy because he felt that someone had to do something. Taking on a project like The Man Who Planted Trees, making it as good as it needed to be, was a way of fighting. Everyone who watches this piece gets the message that one person, with enough dedication, can move mountains. And Back himself certainly did.

The film won Back his second Oscar. It was a TV success and became popular well beyond Canada — Miyazaki and Takahata were just two members of its large following in Japan, for example.

As Back had hoped, The Man Who Planted Trees inspired action: conservation and tree-planting campaigns, and the work of other artists who were stunned by the power of what he’d achieved.

“This tour de force comes up on the screen,” remembered Disney legend Glen Keane, “and it was like every ounce of me as an artist wanted to be Frédéric Back. I was looking at this as one of the greatest works of art of the 20th century, and I still think it is.”

2: Newsbits

This week brought word of the passings of Toei president Osamu Tezuka (62) and American story artist William Ruzicka (45).

In Norway, a film called Three Robbers and a Lion mixes real sets with CG characters. The style came about through sheer necessity, says its director.

Magic Light Pictures in Britain secured yet another hit with its December special The Smeds and the Smoos, which had “8.1 million viewers” via TV and streaming. The studio continues to be one of the most popular (and interesting) today.

The Japanese cult film Noiseman Sound Insect (1997) is currently on Studio 4°C’s YouTube channel. It has English subtitles and will be live until March 17.

In China, box-office data places Deep Sea over 828 million yuan (more than $120 million). Its theatrical run has been extended to March 23. Meanwhile, Wuhu Animator Space interviewed the film’s art director, sharing tons of concept art.

An Italian feature called A Greyhound of a Girl is competing at the prestigious Berlin International Film Festival. It will reach theaters in Italy on November 9. The film boasts character designs by Peter de Sève (Ice Age).

Genius Brands in America supplied the week’s scariest corporate spiel. The company says of its new AI-generated kids’ show: “We’re excited to bring this innovative series to market and, by using ChatGPT, the series is able to quickly and effectively adapt and deliver our content and concepts in a kid-friendly, snackable format.”

In Ireland, Cartoon Saloon’s long-teased Puffin Rock movie is happening. Like with the original series, the team is working with the Northern Irish studio Dog Ears.

Soviet cartoons made outside Moscow were often redubbed into Russian. Now, Ukrainian archivists have uncovered reels from Kyivnaukfilm with the original voices, including famous films like Why Does the Rooster Have Short Pants. Newly scanned prints have been appearing on YouTube for months.

Lastly, we took a peek at the Blender-powered animation process of I Lost My Body (2019), using several lesser-known sources to learn how and why it was done.

Until next time!

Takahata says this in The Nature of Frédéric Back. We’ve never seen him happier than when he meets Back in that documentary. Takahata was a follower for decades: even Grave of the Fireflies (1988) was first planned to use “a loose expressionistic style inspired by Frédéric Back,” according to author Alex Dudok de Wit. Takahata admitted himself that the look of The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013) came from Back’s influence.

From Starting Point 1979–1996 (“Having Seen The Man Who Planted Trees”).

From the documentary The Nature of Frédéric Back, used throughout. Other sources include the books Secrets of Oscar-Winning Animation (2006), The Man Who Planted Trees (2007) and Cartoon Capers (1999); the defunct Frédéric Back website (here, here and here); two AWN interviews (2001 and 2008); and the special features on the Man Who Planted Trees Deluxe Edition DVD set.

great piece thanks!

Beautifully done! I've always loved The Many Who Planted Trees and it's nice hearing more about the story behind it.