Happy Sunday! The Animation Obsessive newsletter is back with another new issue — our last one for January. Here’s the slate:

1️⃣ What makes the César nominee Funny Birds (2022) so special.

2️⃣ Animation news items from around the world.

As always — if you’re just finding us, you can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, every week:

Now, here we go!

1 – Sound and vision

You may have heard Tuesday’s news. The Oscar nominations are out — and not just The Boy and the Heron but the underdog Robot Dreams made the cut. Add in the Spider-Verse sequel, Letter to a Pig and more, and it’s a pretty compelling list.

On Wednesday, though, a different group of nominees appeared across the sea. These were the ones for the César Awards, the so-called “French Oscars.” Tucked away in the animated César picks this year is a remarkable film unlike any in recent memory. It’s called Funny Birds, and it comes from director Charlie Belin.

We were lucky enough to see Funny Birds at a film festival in 2022. It’s been on our minds since then. This recognition from the Césars is well deserved, and a hopeful sign that more people will be introduced to one of the decade’s best films.

At least for now, it’s a film that needs an introduction. Funny Birds, a half-hour piece made for TV and later released in French theaters, isn’t world-famous. For all its awards, it hasn’t swept the festival circuit. You may never have heard of it — it’s been easy to miss.

Still, with this story of a young girl’s journey to return a library book, Belin has revealed herself as one of France’s most exciting animation directors on the rise.

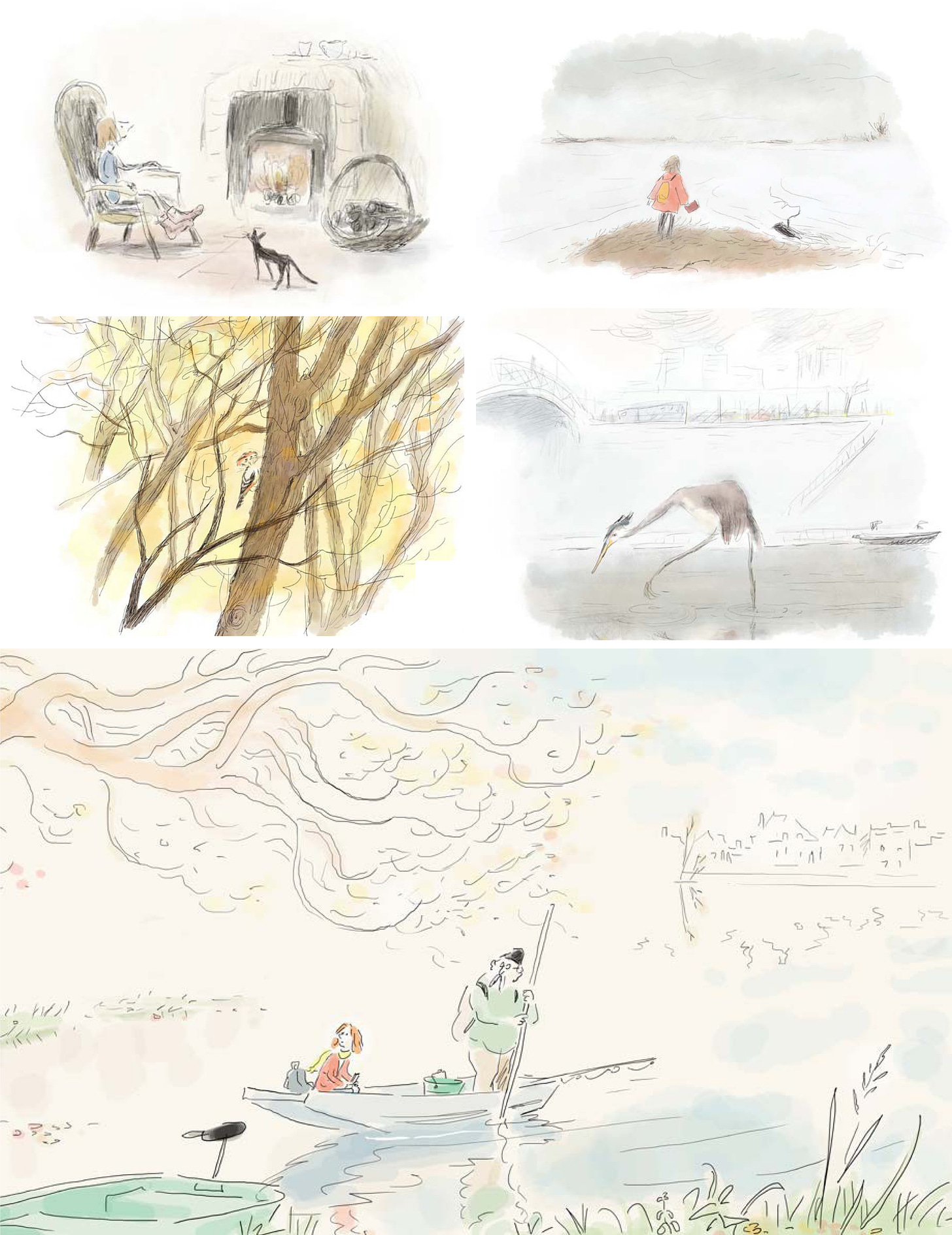

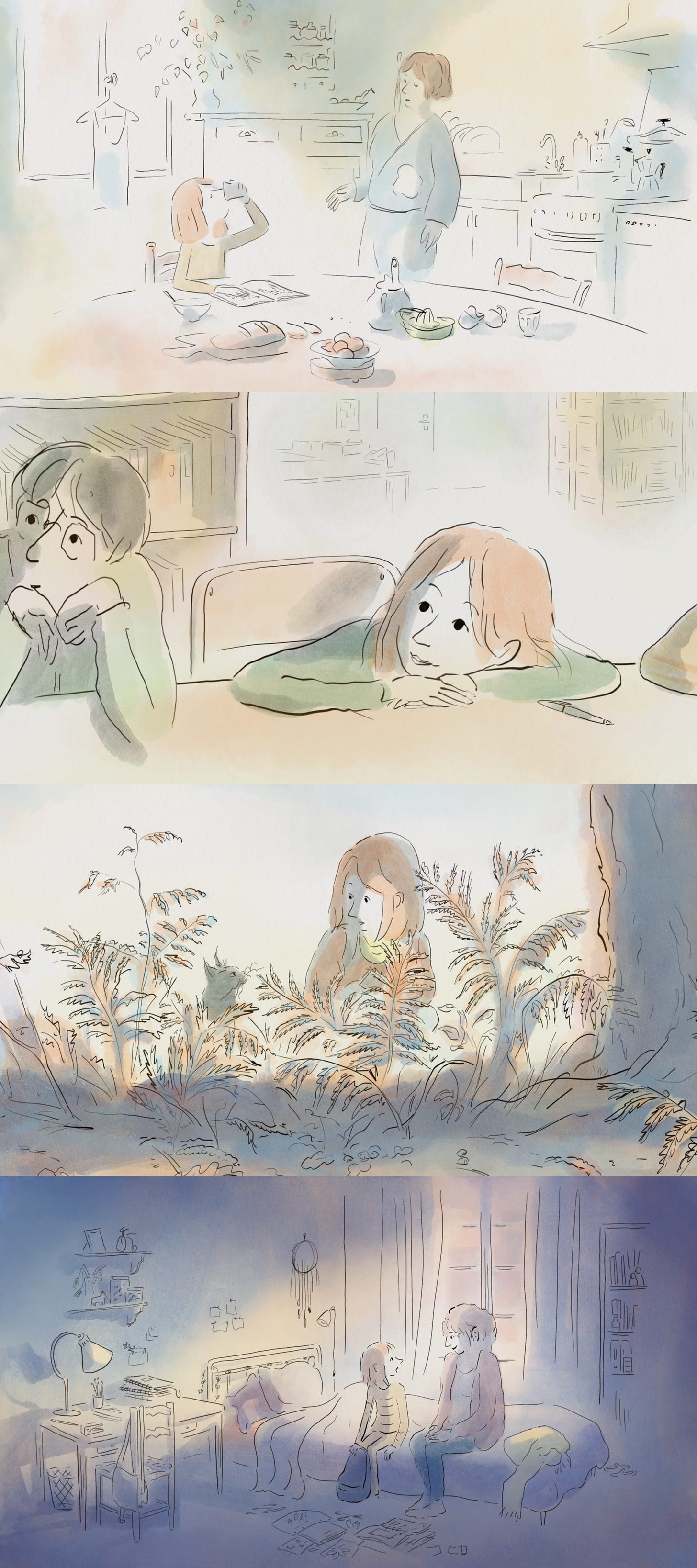

On the surface, Funny Birds is mundane. It’s about the everyday school life of Ellie, a quiet 10-year-old in France. She loves birds and tends to keep to herself, reading. After making friends with the school librarian, Ellie goes to visit her on the small Souzay Island, a place full of wildlife, in the middle of the Loire river.

Slowly, though, the effect of it all sneaks up on you. This film is rich with a specificity and a nearness to the real. It’s in the body language, the movement of a heron that Ellie spots in the river, the feel of the colored pencils that she rolls under her fingers in class. When someone speaks or climbs the stairs or pages through a book, we hear what feels like the raw, natural sound of it. As if a boom mic had been placed in a classroom, or beside a stream.

Everything is tactile — the slime of a snail, the texture of a leaf. And everything is process, down to the way Ellie takes a seat or walks through the tall grass. For half an hour, you exist in Belin’s living, breathing watercolor world.

Which was her goal. As she’s explained:

I really appreciate the ordinary and the everyday. ... What I strive for is how to create fiction while remaining very close to a form of realism. It’s genuine fiction, not a documentary, but at the same time I really drew on documentary elements. ... A key goal is to try to relay life in a quite natural manner.1

Belin has explored similar ideas for years, under the radar. Mixing “documentary” sound with loose, impressionistic art is her signature, dating back even to the student film La Paô (2013). She continued her process on Funny Birds — what she called her “direct sound approach.” Capturing field recordings and building a film around them.

“It’s often real people or places that inspire my desire to make a film,” Belin said last year. “Sound recording and editing precede the image, or take place at the same time, because sound inspires the mise-en-scène, the expressions, the gestures of the characters; it’s a process I need to be creative.”

In the case of Funny Birds, a few real-world inspirations met in the mid-2010s. There was Belin’s familiarity with the Loire river. There were her younger sister and cousin. And there were two stories on the French podcast Les Pieds sur terre (Feet on the Ground).

One episode featured siblings who’d grown up on Souzay Island, which led Belin to explore the place herself. Another involved a woman in college who recounted her childhood, including a memory of “lying on a bench, contemplating the sun through the leaves of a tree in the hubbub of the courtyard.” Both became core to Belin’s idea.2

It came together when she proposed Funny Birds to France Télévisions in 2016, in response to an open call for animated TV specials. “I was attracted by the format of the ‘special,’ 26 minutes,” Belin said. “I felt a slight frustration in making short films ... It was also the opportunity to work on fiction, something I had never done.”3

Ultimately, Funny Birds was accepted. It would take four years to make in all.

Belin has cited a range of artistic influences on this project, including Frédéric Back (The Man Who Planted Trees). “I also watched a lot of Isao Takahata’s films [while working], like Only Yesterday and The Tale of Princess Kaguya,” she said.

In Funny Birds, you sense a Takahata-like interest in reality and in watercolor art. You get it also from Belin’s focus on research, which defined the film.

She prepared Funny Birds mostly alone for the first two years, helped by her sound designer Loïc Burkhardt, her co-writer Mariannick Bellot and by contacts who studied birds. The screenplay set the stage for what was to come. As Belin recalled:

During the writing process, we carefully unraveled anything that might seem too scripted in this story. The challenge was to never drag the story into a “classic” dramaturgical structure, so that Ellie’s micro-sensations were always the strongest, at the heart of the story. The idea was to think of this film a bit like a portrait, to remain all along in the subjectivity of this little girl and in her intimate, sensitive relationship with her observation of the world.

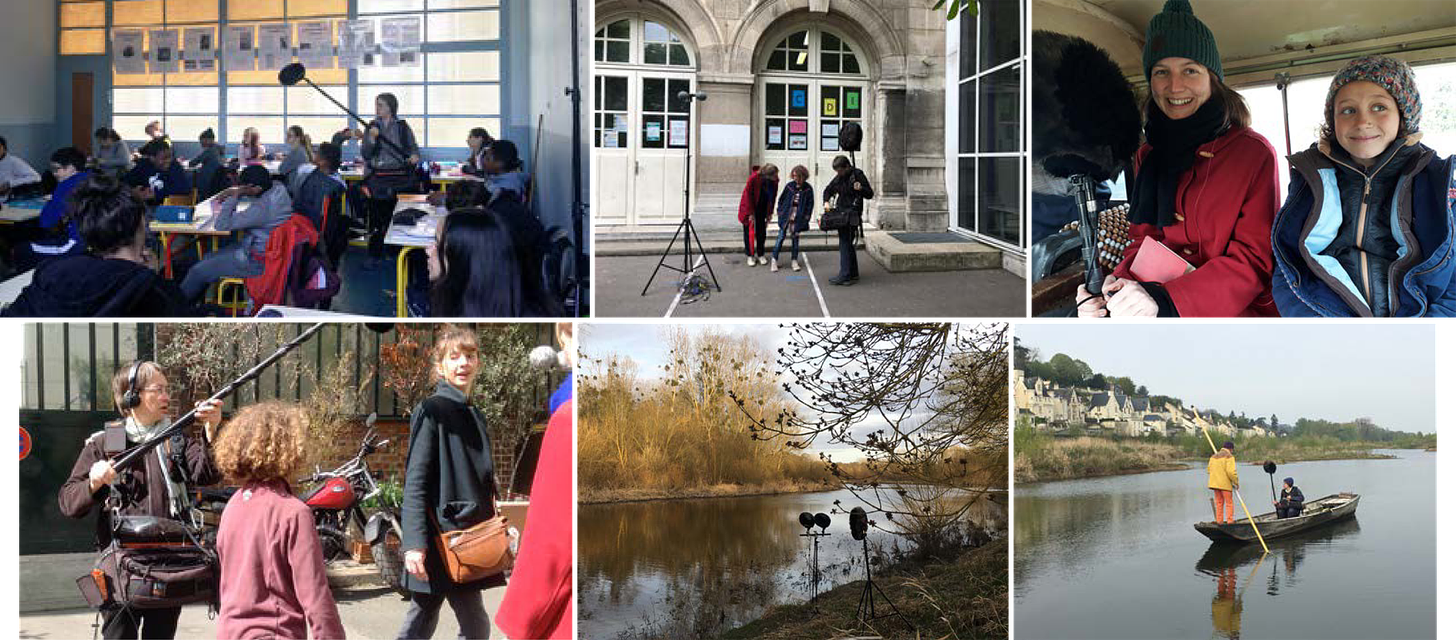

This was followed by Belin’s 2018 residence at Fontevraud Abbey, situated close to Souzay Island. It let her visit the place, sketch, study, meet the few local people and become “immersed in the location.”

Alongside her research trips to this “somewhat mysterious” island, Belin storyboarded at the abbey:

I had the screenplay with me and I recall that initially I was a bit scared of taking on such a huge storyboard, as it’s a 26 minute film. So instead, I worked on rolls of paper, rolls of cash-register paper, on which I inked out the entire screenplay without the constraint of storyboard frames. And this paper roll approach was very practical as it gave me an impression of temporality. So that formed the basis for the making of the film. And it was interesting, because it enabled me to better cope with the pressure of having a very long film to direct.

Her creation of the “first draft” of the audio was a key step in pre-production. There’s no music in Funny Birds — its soundtrack is the sound of the world and everything in it. Belin put together field recordings of voices and ambient noise, embedding herself not just on Souzay Island but in Paris’s Collège Sévigné, where she worked “over an extended period with a [middle school] class and two teachers.”

Belin and the team called audio “the story’s guiding line.” Her first draft showed that Funny Birds could work — it had tremendous energy, as Loïc Burkhardt remembered. For the final soundtrack, they needed to capture this same spontaneous power.

And so the crew went on location again to record the voices with a mix of professionals and non-actors. As the people voiced the characters, they performed the actions planned to appear in the film. You can hear it all happening at once. There was improvisation, and there were mistakes. The moment when Ellie nearly crashes a boat came from a real incident, unscripted, and was kept when animation began.

Belin described it as “a narrative built on the line between fiction and documentary.” Just as the classic Disney animators once based their drawings on footage of live actors, the Funny Birds team illustrated the sounds of things that had really happened. While there were effects added later (bird calls, Foley), live audio was the foundation.

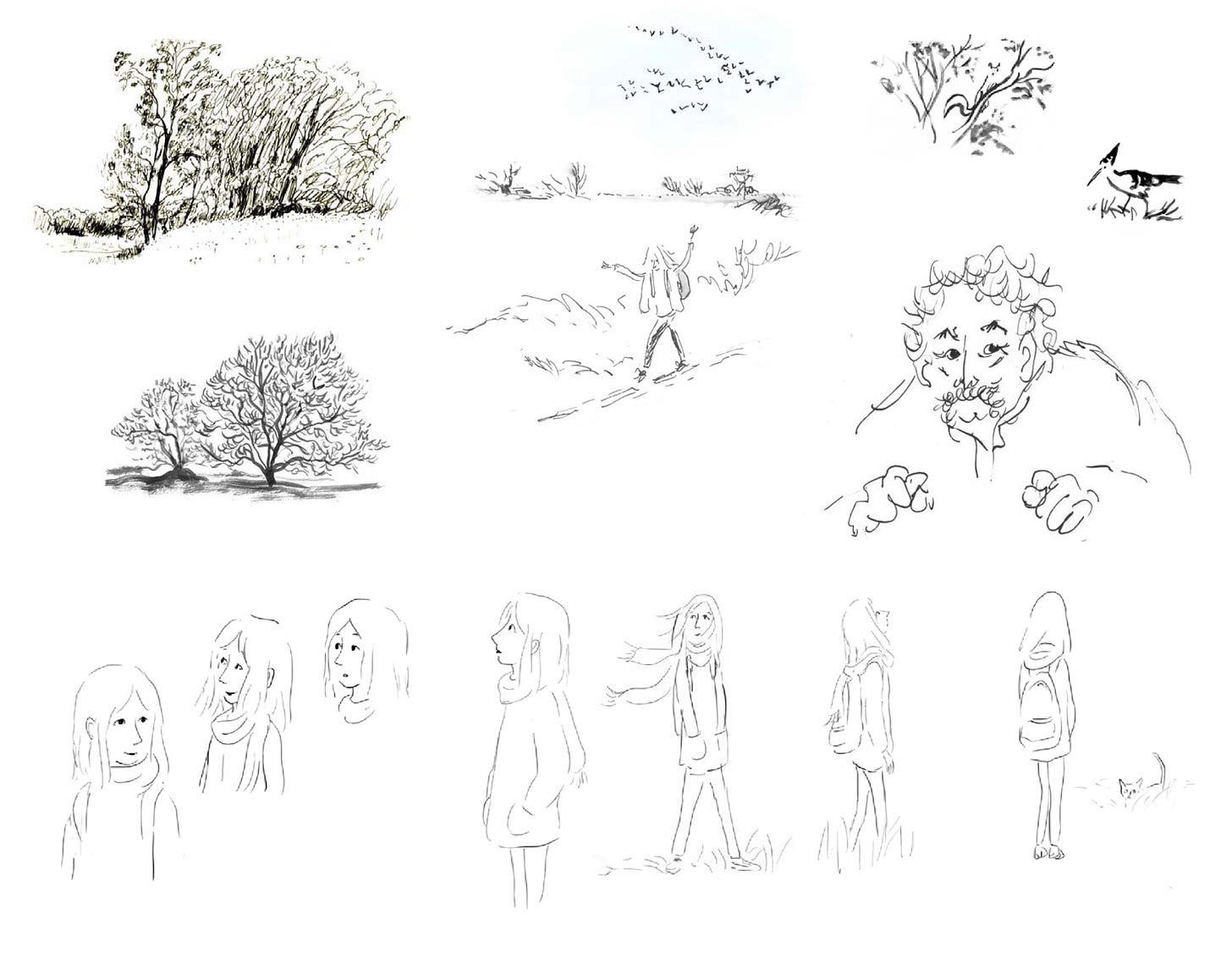

The animation stage in TVPaint had difficulties — the pandemic started while it was underway, and the artists were scattered. But their results are hard to fault. They took Belin’s own loose drawing style (she cites Quentin Blake, Jean-Jacques Sempé and others) and used it to bring believable, hyper-specific performances out of the soundtrack. Each character feels as real as the audio suggests.

Funny Birds’ distributor Miam Animation has put the English version up for free on Vimeo. The embed above works on our website but may have problems over email — if you can’t access it, look for the “full and definitive TV special” on Miam’s site. (The original French Drôles d’oiseaux can be seen here or here.)

It’s an experience worth having. Belin bills Funny Birds as a children’s film — like the Ghibli children’s films that partly inspired it, though, this is a piece wide open to all ages. It’s a meditation on life and a celebration of it. The real world feels more present in the hours after you’ve watched the film.

Back in 2020, the magazine Blink Blank did a story on Funny Birds while production was in progress. A translation of a 1988 essay by Isao Takahata ran in the same issue. In it, he wrote these words about the strength of animated realism:

Take the example of rakugo [Japanese comic storytelling]. A skilled storyteller will bring the expressions and gestures of their characters to life with a palpable presence and an intense sense of reality. Even though we’re all familiar with these most mundane situations, or rather, precisely because we’ve already experienced them and felt their impression, a new emotion arises in the face of this interpretation. It’s precisely that unmistakable feeling that causes you to exclaim, “Yes, that’s it!” to slap your thighs, to reach even the point of laughter or tears.

We often hear that in animation, there’s no need for representations as close as possible to reality, that this medium is not made for that. But I don’t share this point of view. Fundamentally, animation has the same expressive capacity as a rakugo story told by a talented storyteller. This register thus has, in principle, the power to make us reconsider … aspects of existence to which (convinced that we know them all too well) we pay no attention in our everyday lives, nor do we perceive their beauty.

This is what Funny Birds achieves. It shines new light on the mundane, forcing us to look at it and listen to it again. You can’t quite call it hyperrealistic — and there’s no rotoscoping. Instead, the film singles out and amplifies what it wants us to see and hear.

“These moments of life may seem insignificant,” Belin said a few years ago, “but I wanted to take the time to let them exist fully.”

2 – Newsbits

Speaking of the Academy Awards, Our Uniform is the “first Iranian animated short to score an Oscar nomination,” per Cartoon Brew. See the trailer here.

The Imaginary by Japan’s Studio Ponoc (Mary and the Witch’s Flower) has been signed to stream internationally on Netflix this year.

Parallel Studio, based in France, has a slick new animated commercial for luggage.

On that note, check out this retro stop-motion commercial produced in the Netherlands. It’s a dreamlike ad for Philips bicycle lights — an animation restorer uploaded it this week.

Hazbin Hotel, the American indie-pilot-turned-A24-series, is a hit for Amazon.

In Russia, the Guild of Film Critics named Alexander Sokurov’s Fairytale the best movie of 2023, despite its distribution ban in the country. It’s still available on YouTube.

Also in Russia, the success of The Boy and the Heron continues: it’s earned more than 400 million rubles (around $4.45 million). This is reportedly far and away the best performance by a Japanese animated film at the Russian box office.

In Italy, director Victoria Musci spoke to the (English-language) podcast Under the Onion Skin about her film Tufo. It tells the true story of a man’s attempt to stand up to the Sicilian Mafia. See footage of the film here.

In Japan, efforts are underway to document and preserve information about the paint colors used during the era of cel animation. See Animenomics for more.

Lastly, we dove into the making of Chie the Brat, Isao Takahata’s underrated 1981 feature film.

See you again soon!

From this short documentary about the making of Funny Birds, an important source throughout.

Information about the project’s origin comes from the film’s bible, from an interview published by Les Fiches du Cinéma, from BayaM and from the podcast Ecoute ! il y a un éléphant dans le jardin (Listen! There’s an Elephant in the Garden). We’ve referenced these many times today.

From Belin’s interview in the first issue of Blink Blank (January 2020).

Bravo! Funny Birds sounds eerily close to Minimalism in Literature, as it also concentrates on the mundane and all but forces the reader/viewer to feel what the character/s do. Which is why I’m so pumped to check it out… Thanks for this!

We just watched Funny Birds. Thank you for the recommendation. It's beautiful.