Happy Sunday! We’re here with more from the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is a special edition, and it starts with a write-up we’ve been developing for quite some time:

1️⃣ Errol Le Cain, illustrator of the fantastic.

2️⃣ Animation news across the globe.

New here? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues right in your inbox — they arrive every week, for free. It’s a lot of fun:

With that, we’re off!

1: Emerging from obscurity

We got the email around seven months ago. It came from an animation researcher in Britain. His name is Daniel Aguirre Hansell and, back in 2022, he made headlines for finding the lost Richard Williams film Sailor and the Devil (1967). That was a big deal.

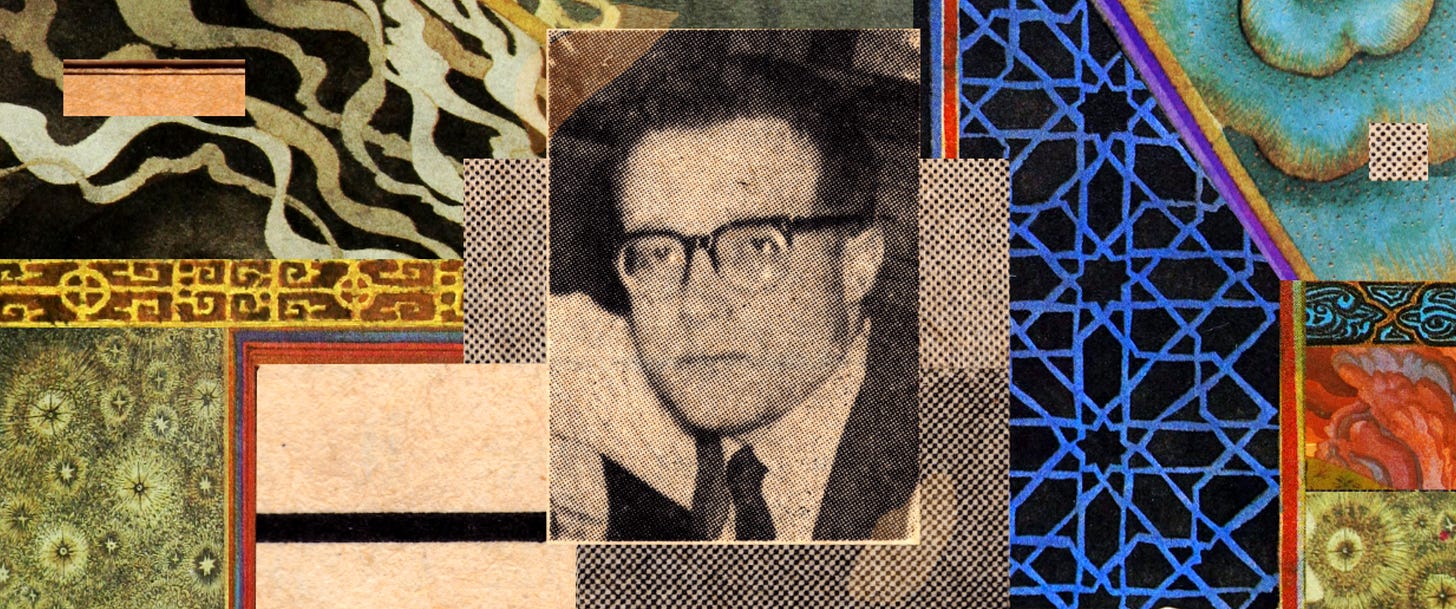

Daniel had exchanged a few emails with us before, but he brought something else this time — an unusual pitch. He wanted to turn his latest research project into a story for our newsletter, written by our team. The subject was Errol Le Cain.

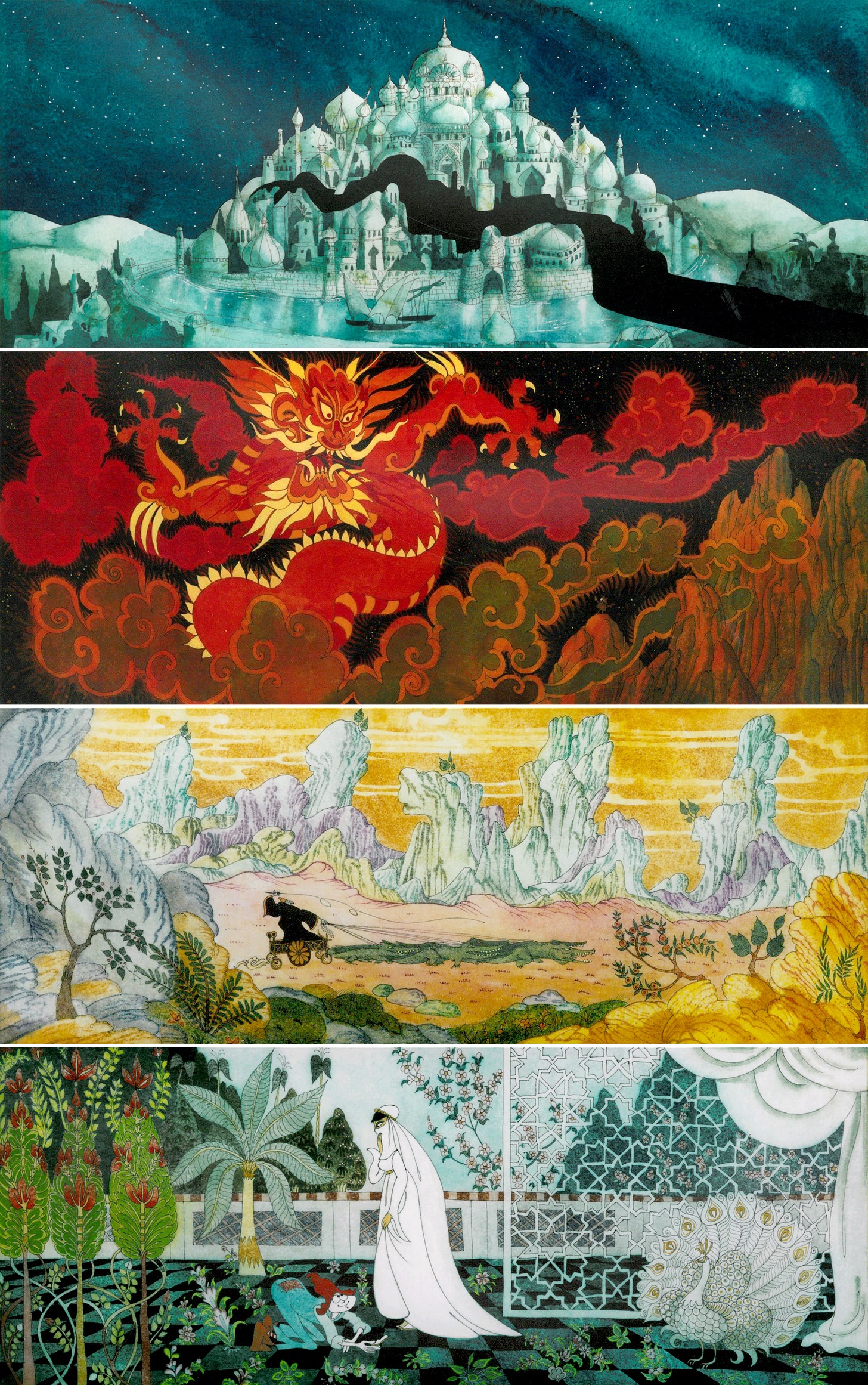

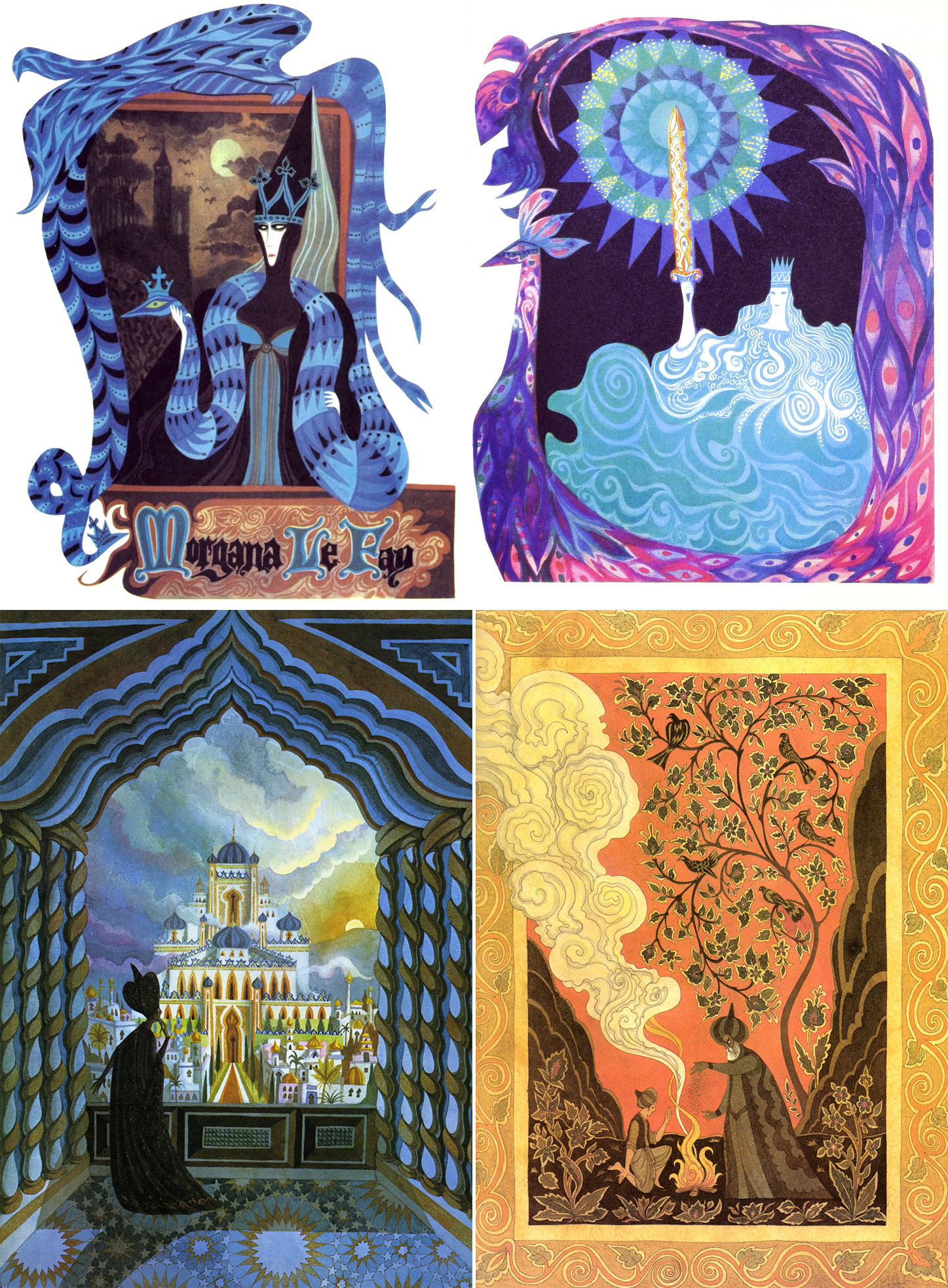

Le Cain was a 20th century illustrator and designer and animator, and he’s been called one of “the most influential artists on Richard Williams’ The Thief and the Cobbler.”1 He was essential to setting that film’s visual style — those hypnotic backgrounds inspired by Persian miniatures. Anyone who’s marveled at the look of Williams’ unfinished magnum opus can, in part, thank Le Cain.

Williams kept Le Cain around as a trusted collaborator — he was behind Sailor and the Devil, in fact, and was renowned for his children’s books to boot. But Le Cain’s name has faded since his death in 1989. He has a degree of fame in Japan, and that’s about it. His son, the experimental filmmaker Maximilian Le Cain, said in an interview:

In this part of the world, whenever I find mention of him, it’s normally the odd post online by someone who either grew up with his work or has just discovered it expressing amazement at how little known it is. Or how completely forgotten. It’s of a style and a sensibility that seems to have vanished. Errol’s is a phantom legacy representing a quality that seems to be of another age.2

Today, with the help of Daniel’s research, we’d like to shine a light on the life and beautiful work of this lost artist.3

It was in the mid-1960s, in London, when Richard Williams hired Le Cain. He quickly stood out as a versatile and driven talent at 13 Soho Square, Williams’ studio address. A co-worker recalled, “Errol Le Cain, he was a genius. Didn’t go to art school. … I mean, he would sit like a monk on a chair and he would just go.”4

This was decades before Roger Rabbit. Back then, the Williams team was known for TV commercials, short films, movie title sequences. Le Cain took part in the animation for Casino Royale (1967) and The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), for example, and served as director-animator on the short Sailor and the Devil — a manic, boogie-woogie head-trip.

Williams called Le Cain “wonderful” and said that, even as an animator, he was “getting really hot” before Sailor was finished.5

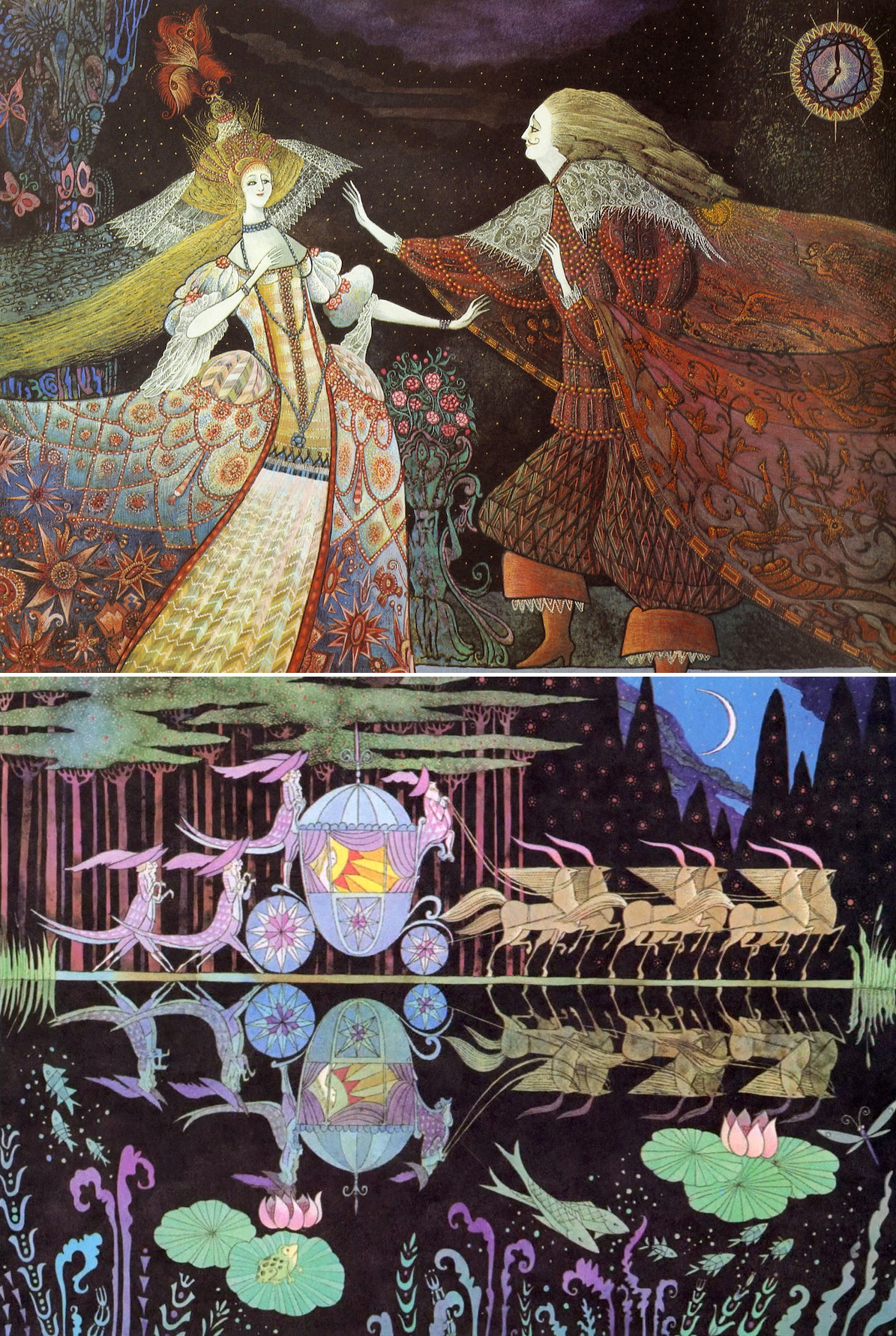

Le Cain’s design and painting, too, were first-class. Besides his studio work, he began to publish picture books like the gorgeous King Arthur’s Sword (1968). One of his later collaborators, author Rosemary Harris, wrote this about Le Cain’s artistic process:

It’s hard to describe Errol’s extreme involvement with his painting — it was an almost bodily thing, which dominated all his waking thoughts. Pictures flowed out of him as though his fingers were the brush and the other end of the handle was his mind. A rough text sent to him would produce within days the color roughs and sketches for an entire book, filled with original and witty touches. […] He looked so frail, and seemed to be a channel for something so large.6

Le Cain’s sensibility as an illustrator helped to define Williams’ dream project The Thief and the Cobbler long before it had that name. In the ‘60s, it was called Nasruddin for a time — an independent, overambitious, constantly-morphing film.

Le Cain stayed a mover on the feature as it evolved. Many, many of the background paintings in the final version came directly from his hands, and the rest were based on his style. He was central to the concept art as well. “He played a huge role in creating the look of the film. Early on he did a lot of inspirational illustrations to establish the style,” wrote Holger Leihe, who animated on Thief.

Another person with knowledge of the production noted Le Cain’s “distinctive color sense,” and wrote that Williams often had him paint scenes as soon as feasibly possible, well before the actual animation was complete. “I guess Dick figured that Errol was unique,” wrote that observer, “and he wanted to get him to do as much of the film as he could by producing the backgrounds as soon as they were ready to go.”

Le Cain was unique. Even the reviewers of his picture books could see it. When The Times wrote about his Cinderella in 1972, it classified the beauty and intricacy of Le Cain’s artwork as a “sort of assault”:

… he has produced a series of black-and-white and colored illustrations of overwhelming accomplishment. The brisk, purposeful telling of Cinderella’s happy adventure has been surrounded by a luxury of ornament — decorative borders, Beardsleyesque designs, pictures resplendent with the color and delicacy of the most refined court in Fairyland.

That kind of richness shot through Le Cain’s work for title sequences, and for The Thief and the Cobbler.

On all of these projects, his reference points varied. He loved the traditional art of India, Japan and the Middle East — to name a few — and it infused his paintings. But he didn’t approach this stuff from a tourist’s perspective. Le Cain was guided in part by his own background. He lived a winding, unexpected life and learned his trade in his own way.

Errol John Le Cain was born in Singapore, in March 1941, when the country was under the colonial rule of the British Empire. His family tree was Eurasian — and had been for several generations. Le Cain’s father, a member of the police force, would eventually rise to become Singapore’s first Asian police commissioner.

But that was much later. World War II was on when Le Cain came into the world, and Japan invaded in 1942. His father ended up in an internment camp. At 11 months of age, Le Cain was evacuated to India.7

His time as a refugee in the city of Agra, where he spent around four years, would shape him. This was his first memory: what he recalled decades later as a “rich and varied world.” Le Cain spoke of the dust storms, the puppet shows based on the Ramayana. For his childhood self, the Taj Mahal was “that old building on the way to school.” His home was a hotel where he lived with his grandmother and mother.

“We spent most of our time on a large veranda looking out over a dense and beautiful garden,” he wrote as an adult, “which flourished in spite of the dryness of the surrounding area.”

His grandmother, a maker of dolls and dresses, could be found “in her white fluffy hairnet, stuffing the bodies of dolls with cotton.” Around the age of four, Le Cain encountered his first picture book — Alice in Wonderland, featuring John Tenniel’s illustrations. In Le Cain’s words:

It was the only English book we had in the hotel and it was from it that I really learned to speak English. I had spoken only Hindustani until one day my grandmother decided that I must learn to speak English too, so she took my “education” in hand and taught me by telling me all the stories that she knew in English — The Pied Piper of Hamelin, Rapunzel, Pinocchio, Aladdin, The Wizard of Oz (remembered from the Judy Garland film) and the stories of Monkey.

Le Cain’s life in Agra ended with the return of his father, freed from internment in September 1945. The war was over — the family went back to Singapore. But all he’d experienced would impact his future style.8

Le Cain was drawn to art from a young age — always in a free-spirited way. In kindergarten, his spirit was free enough to get him “banned from art classes,” a sign of things to come. Later, he would enter his career essentially without a formal arts education.

While not much of a student, he was “always drawing and painting at home,” he said. As a child, Le Cain created his own picture book based on his grandmother’s Aladdin story, and drew his own illustrations in the margins of a pictureless Hans Christian Andersen book he received as a gift.

What truly led him to his passion, though, was the Roxy Cinema. It was a popular movie theater located in Singapore’s Katong neighborhood. The Roxy showed films from around the world, including Hollywood productions like Casablanca. Le Cain went there again and again as a young boy. In his words:

The Roxy was really where I was educated. It used to change its programs twice a week, and I knew how to get in behind the screen so I’d see the films back to front. I saw everything. Those films were my art training.

Le Cain wasn’t watching movies as most do. They were, as he noted, reversed. They were also out of focus, on account of his eyesight. His son Maximilian wrote:

… I’m deeply haunted by Errol’s description of sneaking into cinemas as a child before he started wearing glasses and watching films hidden behind the screen. What he saw were semi-abstract swirls of light and movement, up close and backwards. These intense experiences, lost when his vision was brought into focus by glasses, certainly connect with my interest in experimental film.

For Errol Le Cain, film became the main thing. At age 11, he began to animate with stop-motion cutouts, using a friend’s 8 mm camera. As a teenager, he got a 16 mm camera from his parents and animated The Littlest Goatherd in two months, in color. It was silent and shot at 16 frames per second, but was by all accounts an endearing and creative fairy tale. A viewer recalled its “immense charm, naivety and character.”9

By 15 or 16, Le Cain was out of school and without a roadmap for the future. Yet his Goatherd film got the attention of a British advertising agency, Pearl & Dean, that had people in Singapore.10 Around 1956 or 1957, the agency moved Le Cain to London as a promising young hire. There, he would work in animation.

The teenage Le Cain was a “quiet, nervous boy,” as one London observer remembered him. He didn’t grow out of this reserved phase. Le Cain was deeply shy in adulthood, with a “slightly forlorn air” and a tendency to be “very depressed,” according to people who knew him. Some who didn’t know Le Cain underestimated him as a “curious waif and stray.”11 Yet his talent and enthusiasm were already clear in his teens.

Le Cain earned money with commercial work, but he soon fell in with London’s amateur filmmaking scene on the side. By age 19, he had ties to the Grasshopper Group, which historian Jez Stewart has called “a support network for aspirational and experimental” animation. Luminaries like Gerald Potterton (Heavy Metal) and the Oscar winner Bob Godfrey came up through it.

So did Le Cain. He impressed the Grasshoppers with The Littlest Goatherd and became one of their respected members, creating more ambitious and complete films with their help. Among these was Victoria’s Rocking Horse, the most decorated Grasshopper Group project of 1962.12

The British TV presenter Steve Race raved about that one’s UPA-style design and use of a four-year-old narrator. “Extremely elegant. No clumsy passages. Voice perfect,” wrote Stanley Reed, the soon-to-be director of the BFI.

Despite the praise, Le Cain’s production process was still far from studio-grade. The young animator stole spare moments after work to create the backgrounds and paper-cutout characters for Victoria’s Rocking Horse, and animated it by sunlight on the weekends. At the time, a letter to the magazine Amateur Cine World noted that Le Cain:

... goes out on to the roof of his home with an old Kodak camera and tripod. He sets up his cutout figures in a very Heath Robinson manner and starts to film them, hoping like mad that the sun won’t go in or come out as the case may be. (Did you notice the variations of exposure in the film?) He also trusts to luck that a sudden gust of wind won’t blow the whole damned lot into the street below, although one whole sequence was lost through this very catastrophe.

Over the next few years, Le Cain kept practicing his craft in the underground scene while earning his living elsewhere. His original job with Pearl & Dean ultimately didn’t last long, maybe a year, but he bounced to a second advertising agency and to a design position at the animation studio Moreno Cartoons. A fellow member of the Grasshopper Group called him a “cog in the wheel of a mechanical cartoon set-up.”13

In early 1965, Le Cain’s big break arrived when Richard Williams hired him as a full-time staffer. It was especially the amateur work, like The Cage (1965), that seems to have drawn Williams. This new job marked the end of Le Cain’s time with the Grasshoppers — he was under an exclusive, professional contract now.

And so it went. Richard Williams Animation was a creative but often brutally busy place — stories were passed down of the crunch on Light Brigade, the collective bed in the studio for exhausted crewmembers who didn’t have the time to go home.

Le Cain turned freelance in the late ‘60s, but he kept working for Williams on The Thief and the Cobbler, spending over two decades with it. Maximilian Le Cain, born in 1978, remembered visiting the Williams studio with his father even in the ‘80s.

But Thief was one project among many. Errol Le Cain’s name appeared on a new children’s book almost every year, after Williams showed his artwork to the right publishing people around 1967. (Le Cain was reportedly too shy to pitch his own books at first.) And he worked a lot in film and TV — including the design and layout for Cat Stevens’ 1970s Moonshadow animation, embedded above.

The work went on and on like this. Really, he was a workaholic. Maximilian recalled bonding mainly near his father’s workstation at home. “I’d sit on the floor and read or draw or he’d tell me stories,” he wrote. “He never minded me being around while he worked and these are good memories.”

There were plenty of good memories of Errol Le Cain — among friends and family and co-workers. He was a warm and generous figure, quiet but eager to help. When he died from an illness at just 47, he felt that he had years more to give. “I want to keep working,” he wrote in 1988. “I’ve still got so much to do.”

In the end, even The Thief and the Cobbler was left unfinished — it exists, today and forever, as a project watchable only in part. It’s a phantom film, a fragment of Le Cain’s own phantom legacy.

Right now, Le Cain’s books are mostly out of print. Some of his acclaimed early animation, like The Knight and the Fool and Victoria’s Rocking Horse, is preserved but unavailable to the public. The full version of Sailor and the Devil only resurfaced in 2021, thanks to the same researcher who gathered the material for today’s issue. It’s in the care of the BFI, but yet to be released.

Even so, a phantom legacy is still a legacy. Le Cain’s picture books really are cherished by those who know them — and he really does have a name in Japan, where a museum held an exhibition of his work as recently as 2019. The impact of Thief alone has radiated outward for decades. Its style is part of Cartoon Saloon’s DNA — seen first in The Secret of Kells (2009) and later in Wolfwalkers (2020), both Oscar nominees.

Le Cain’s art has the power to wow even today. You catch his illustrations popping up on social media, Twitter and Tumblr, for their ethereal fairy tale look and feel. A 4K restoration of Moonshadow came online just in December 2021 — many love it, too.

He may be a phantom, but Le Cain isn’t a footnote. Something valuable is hidden here that rewards the people who find him. And finding him seems to be getting easier by the year. This is a long, slow process — but Le Cain’s work is coming out from the obscurity in which it’s languished for so long.

2: Animation news worldwide

Africa rising

The story doesn’t always get major headlines, but the 2020s have been a time of tremendous growth for animation in Africa. As more and more opportunities open up, more and more artists join the trade. It’s a pan-African phenomenon. And July 2023 has been one of its biggest months so far.

As you might have heard, Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire came out in early July. The Disney+ anthology, sourced from across Africa, continues to get attention. Uganda’s Independent looked into the people behind the series this week, and quoted episode director Raymond Malinga (Uganda) about his decision to study animation in school:

You have to understand. Back in those days when people heard that you wanted to go and pursue a career in animation, you would often get reactions like, “Are you crazy?” “Will you make money?” “Will you achieve anything?” How will you be useful in society?

Given that Malinga’s episode is the first in Kizazi Moto, streamed around the world to positive feedback, it seems those questions have been settled. But Malinga isn’t resting. As he told Plugged Uganda this month, “For me, my aim was, ‘How do I tell a Ugandan story that when someone else in Uganda sees it, they will sense that we are capable of telling these kinds of stories?’ ” He’s trying to “build the Ugandan industry.”

The main organizing studio on Kizazi Moto was Triggerfish, based in South Africa. It isn’t resting, either. Triggerfish had a second major launch this month: Supa Team 4, reportedly the first African animated series produced by Netflix. Like Kizazi Moto, it has pan-African roots — its creator, Malenga Mulendema, is Zambian.

In an interview with Nerd Otaku Zambia, Mulendema recalled joining Triggerfish’s Story Lab program back in 2015. “I thought, ‘Well, workshops are a great way to get into a space where you can learn, you can try,’ ” she said. Completing something as huge as Supa Team 4 wasn’t realistic. But things developed to this point.

As the head of Triggerfish said to Nigeria’s TechCabal this week, “Africa is full of stories; storytellers just need more opportunities to tell them.”

Triggerfish isn’t the only studio offering those opportunities. In mid-July, the Nigerian series Garbage Boy and Trash Can premiered on Cartoon Network Africa after more than four years in the works. And the children’s series Nuzo and Namia, from Tanzania, debuted in June. Supported by the LEGO Foundation, it teaches kids about diversity and is gradually launching throughout Africa.

Newsbits

Hayao Miyazaki’s final film, The Boy and the Heron, will have its international premiere in Canada this September — at the Toronto International Film Festival.

In Japan, TV anime has long been split into daytime series for families (One Piece, Sazae-san) and late night shows for superfans. That barrier is breaking down as anime gains in popularity, argues Tadashi Sudo. One sign: Nippon TV is putting an anime series (Frieren) in its prime-time Friday Road Show slot for the first time.

We saw the French short Horacio at a festival a few years ago — it never left us. Now, this unsettling story of murder and psychopathy is online with subtitles.

The long-awaited stop-motion film The Inventor, co-produced in America and France and beyond, is coming to US theaters in August. See the trailer.

In China, Chang’an has surpassed 1.5 billion yuan (over $210 million). It’s now the highest-grossing animated film of the year in China, and it may yet topple Jiang Ziya (with around 1.6 billion yuan) to become the #2 Chinese animated film ever.

One more about animation from France: the sequel to Ernest & Celestine hits America in September, and there’s a trailer.

Japanese director Hiromasa Yonebayashi (Arrietty, Mary and the Witch’s Flower) was hospitalized following a heart attack. He writes that he’s recovering. This comes after the serious bicycle accident that sent him to the hospital in 2022.

In America, the East Coast branch of the Writers Guild promises to incorporate animation writers after the strike ends — which could be massive for the mostly non-union Eastern animation scene.

Pixar’s Elemental continues to be a runaway success in South Korea. With roughly $44 million at the box office (per Kobis), it’s reportedly the country’s top foreign film of the year and third-biggest animated film ever, behind Frozen and Frozen II.

Lastly, we looked at the underrated artistry of in-betweening.

See you again soon!

From an unpublished email interview between Daniel Aguirre Hansell and Maximilian Le Cain, conducted between October 14, 2021, and November 7, 2022. We cite it throughout.

Per Daniel’s request, we extend his special thanks to Maximilian and Frederika Le Cain, Richard Clement, Robert Wyn, Max Prineas, Davide Simonetti and ArchivistMemes — “all of whom have been incredibly helpful with my research,” Daniel wrote.

Designer Roy Naisbitt, a key figure on The Thief and the Cobbler’s backgrounds, said this to Garrett Gilchrist in a 2006 phone interview. It’s in the third Thief and the Cobbler scrapbook.

Richard Williams comments on Le Cain’s animation in The Creative Person (1967), and calls him “this wonderful guy we’ve worked with for many years” in I Drew Roger Rabbit (1988).

From The Guardian (January 6, 1989). The Cinderella review is from The Times (June 14, 1972).

The information about Le Cain’s father is taken from the government of Singapore, while Le Cain’s date of birth is in the Sixth Book of Junior Authors & Illustrators. Most of the details about his childhood come from Books for Keeps (November 1987) and his article Childhood in India (1976) — the former is a major source across the entire piece.

It’s often been claimed that Le Cain traveled widely throughout Asia in his youth, but his biographer Denyse Tessensohn argued that this isn’t true. “Apart from his very early few years during WWII in India as a refugee, he only traveled a couple of times into nearby Malaya,” she wrote. As an adult, Le Cain apparently made it to Japan.

The Littlest Goatherd is discussed in Amateur Cine World (September 1960, February 18, 1965). Accounts vary as to his age when he made the film and left for London. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature (2006) puts his departure in 1956, while Amateur Cine World (May 2, 1963) had it in 1957. Books for Keeps implied that he was 15 when he made the film — he’s 16 in the account from “The Very Best Aspects of Book Illustration” (1999). We reference these sources throughout.

According to a 1959 report by the U. S. Department of Commerce, the Singapore office of Pearl & Dean employed 18 people. The company also had branches in Malta, Nigeria and Cyprus at that time.

The notes about Le Cain’s appearance and vibe come from Books for Keeps (March 1989), Amateur Cine World (February 18, 1965) and Daniel’s interview with Davide Simonetti (March 24, 2021).

Amateur Cine World named Victoria’s Rocking Horse one of the “Ten Best” amateur films of 1962 — a prestigious award. At a National Film Theatre screening of the year’s winners, the judges picked Victoria’s as their favorite. It also won a prize at the Scottish Amateur Film Festival. (In fact, almost two decades later, the magazine Movie Maker was still citing Le Cain’s film as a standout for the Grasshopper Group.)

Director John Daborn wrote this in his letter to Amateur Cine World (August 29, 1963). Many sources claim that Le Cain stayed at Pearl & Dean until he moved to Williams’ studio in 1965, but “The Very Best Aspects of Book Illustration” has that job ending after a year. Amateur Cine World (May 2, 1963) seems to back this up: “He worked with two advertising studios before joining the cartoon film company where he now works as a designer and background artist.” Moreno Cartoons in London appears to have been that company — animator Peter Hale offered a few details in his comments here and here.

I love that you have put the spotlight on Errol Le Cain I loved his books as a child long before I began working in animation. I would spend hours poring over the pages, I collect them now and still do.

I loved the "cobbled" together version of Thief and the Cobbler that I saw once, and now I know whose art was behind much of it. Thank you for sharing his beautiful work.