Happy Sunday! We’re back!

At the end of June, the Animation Obsessive newsletter went on its planned mid-year break. In the time since, we’ve done tons of prep — studying animation from China, Japan, Britain and beyond. We translated a miniseries, worked with outside collaborators and even found time to unwind (the Swedish live-action series Huss was a highlight).

Now, we’re here with a lead story we’ve wanted to do since 2021. This is the plan:

1️⃣ Behind the scenes of Magnetic Rose (1995).

2️⃣ Animation news worldwide.

If you haven’t signed up yet, it’s free. Get our Sunday issues right in your email inbox — there’s great stuff ahead:

With that out of the way, we’re off!

1: Splendor and decay

Magnetic Rose is one of the best. Not everyone knows about this creepy, haunting piece of anime sci-fi, but they should. It’s a short classic of the ‘90s — a film that puts more emotion, awe and excitement into its 40 minutes than you get from the average two-hour movie.

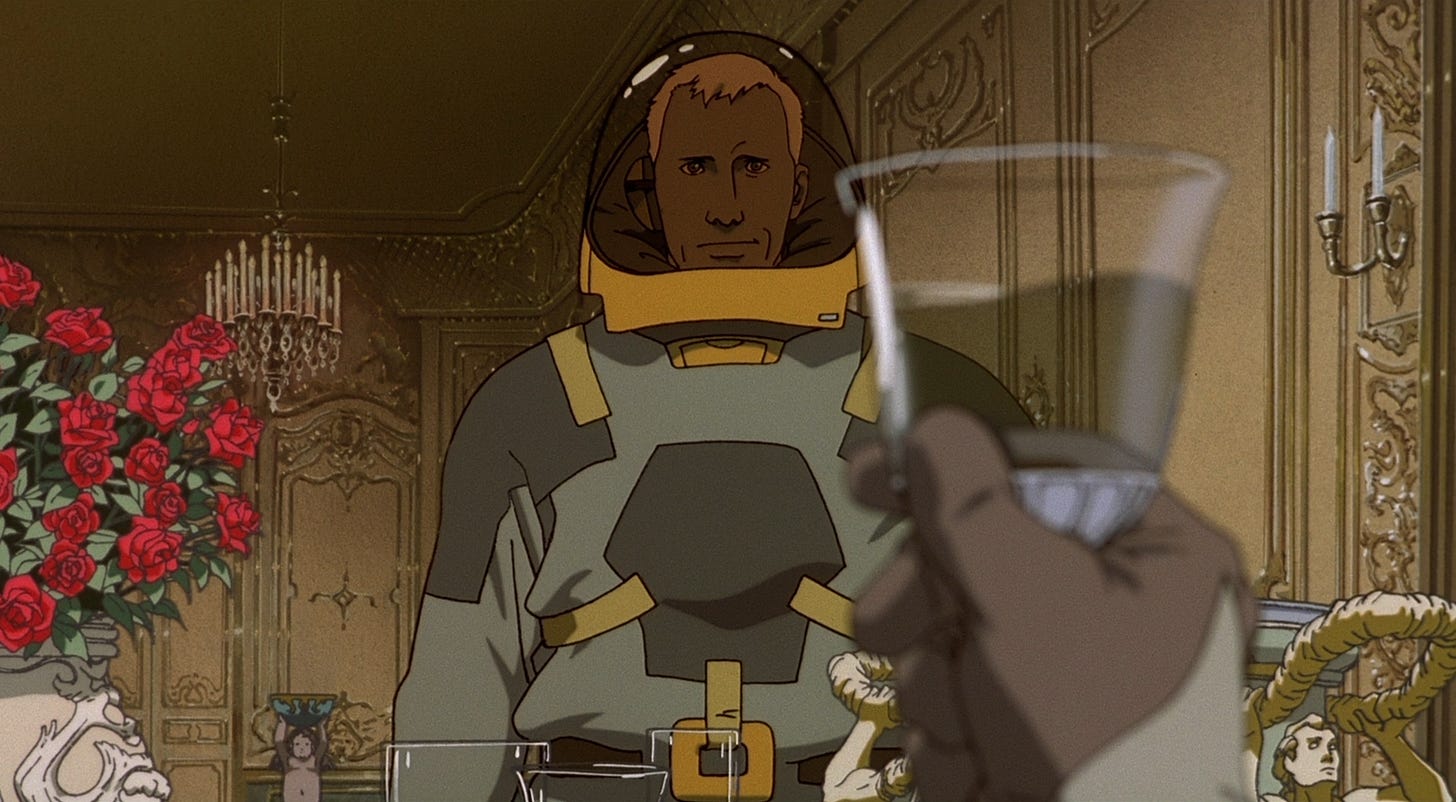

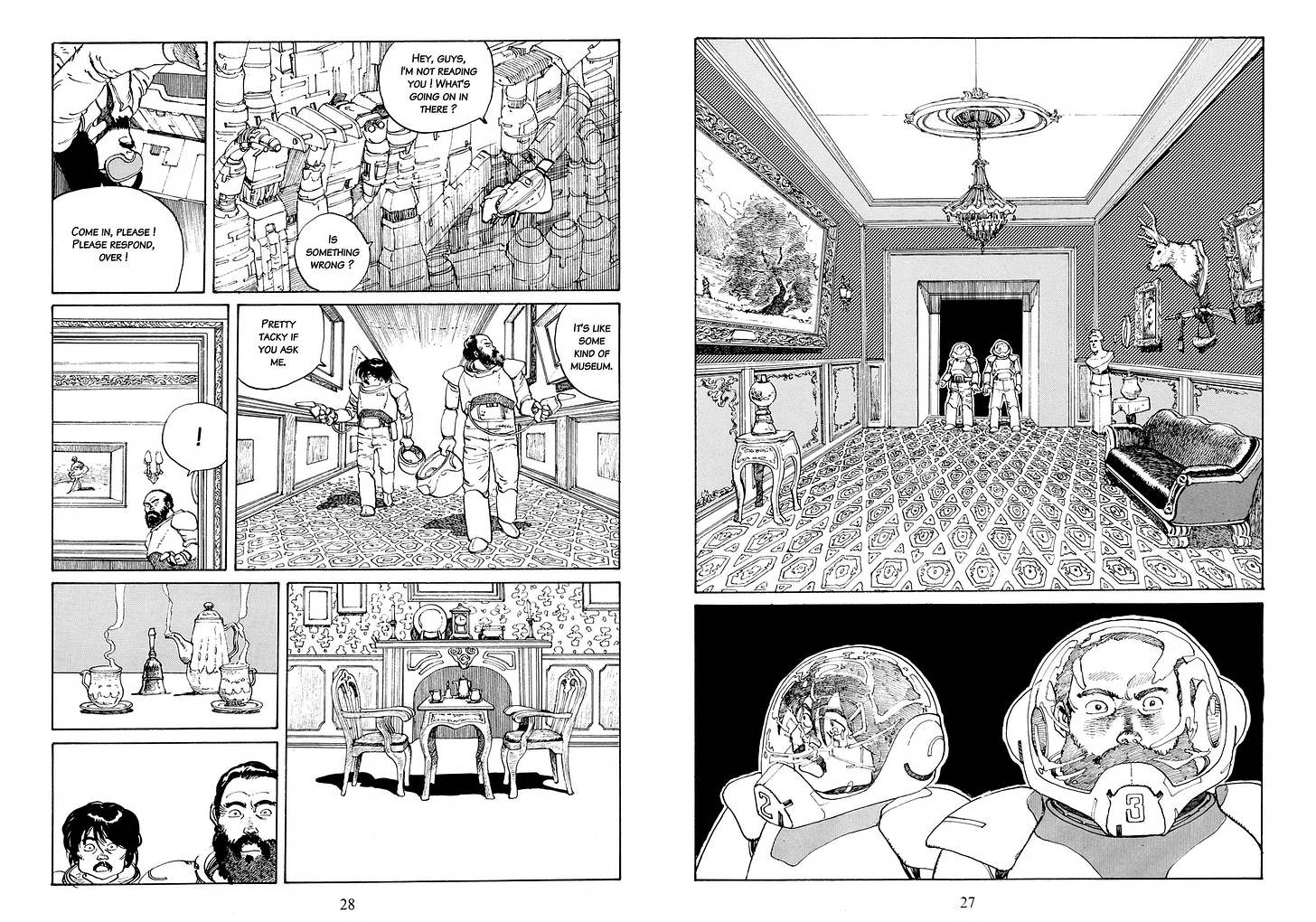

Its premise seems a little straightforward, even basic, at first glance. In the future, a spaceship crew follows a distress call to a lost station — which is shaped like a rose, and radiating magnetic energy. The station seems empty, but something’s off. Inside, reality and hallucination start to bleed together. Fighting to stay sane (and alive), the rescue team uncovers the mystery of the opera singer who created this place.

It sounds cool, but not necessarily groundbreaking. What makes Magnetic Rose so special is its execution: the strong filmmaking and powerfully realistic animation, the atmosphere, the music and story structure. It creates a world that it doesn’t let you leave.

The short debuted in Memories (1995), a film anthology by Katsuhiro Otomo of Akira fame. He oversaw an all-star team here. On Magnetic Rose, you find Yoko Kanno (Cowboy Bebop) as the composer, and a young Satoshi Kon (Paprika) as the screenwriter. The short’s director, Koji Morimoto, was himself a key player on Akira. Meanwhile, the animation staff included some of Japan’s finest.

Magnetic Rose isn’t the only standout in Memories, but it’s the most ambitious of the bunch. And it wasn’t easy to do. “Although it was a collection of stories,” said Koji Morimoto, “we knew Magnetic Rose was basically our centerpiece for the project, and the pressure to get it right was intense.”1

Memories had a rocky start. At first, Magnetic Rose wasn’t even supposed to be in it.

Back in 1990, Otomo released a manga anthology called Memories. “When I published my collection, there was talk of picking up some of the stories and turning them into anime,” he said. The idea was to take three of his manga shorts and base a straight-to-video project on them.2

During this early stage, Koji Morimoto signed on to direct the sci-fi entry A Farewell to Arms — Studio 4°C was set to animate it.3 Ultimately, though, the straight-to-video Memories “ended up falling through” because it “couldn’t be done at a video level,” according to Otomo.

Yet things didn’t end there. As Otomo explained:

… since the plan had been made at great pains, we decided, “Let’s do it.” And so from there Bandai entered and it gradually materialized. … But when Bandai joined the project, they decided to make it into a theatrical film. However, I was opposed to it at first. I thought it was made for video, so I didn’t know whether it would be a hit as a movie. I said that … it’d be better to do a proper story for theaters — but, for now, let’s do it in the form of an experiment. Before doing the next big project, we started talking about whether it would be okay to try this sort of thing once. Since the staff was getting scattered after Akira was over, we said, “Let’s gather everyone again.”

Along the way, they reshuffled the project. Otomo felt that A Farewell to Arms “lacked splendor,” and so Magnetic Rose was chosen as a better fit — a bigger, more visually rich story. Morimoto was keen to direct it at Studio 4°C, too. He later recalled:

At the time this story was created, there weren’t a lot of true-to-form science-fiction titles out there. ... Mr. Otomo’s story hit on just the right atmosphere, like something resembling a Yukinobu Hoshino manga. I was interested in that aspect, of course, but I also liked the idea of going into space, such as with Tarkovsky’s film Solaris.

The influence of Solaris would be visible throughout the animated version of Magnetic Rose — much more than in Otomo’s original story.

In fact, the whole short drifted pretty far from Otomo’s style, and his input on it wasn’t huge. “Mr. Kon and I used to say we had to escape the magnetic field called ‘Otomo.’ Otherwise, we wouldn’t succeed,” Morimoto said.4

The need to get away from Otomo’s manga wasn’t obvious at first. Satoshi Kon’s initial few drafts of the Magnetic Rose screenplay stuck to the source material.

At the time, Kon was an up-and-comer. He’d broken into the anime industry through his assistant job on the Akira manga — Otomo brought him over to help with the film Roujin Z (1991). From there, Kon bounced to Run, Melos! (1992), which we’ve covered before. Then, like many Melos staffers, he wound up on Magnetic Rose.

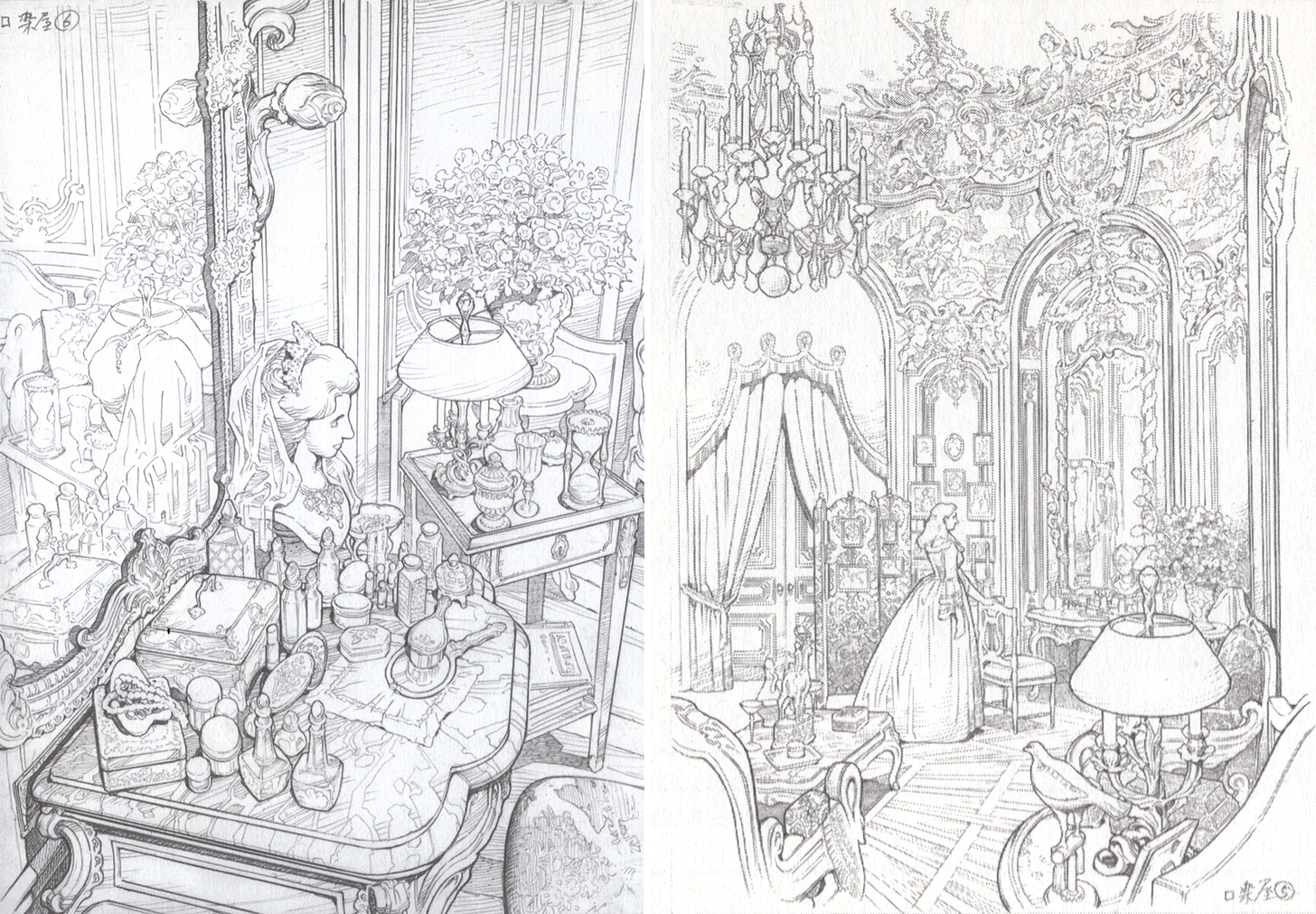

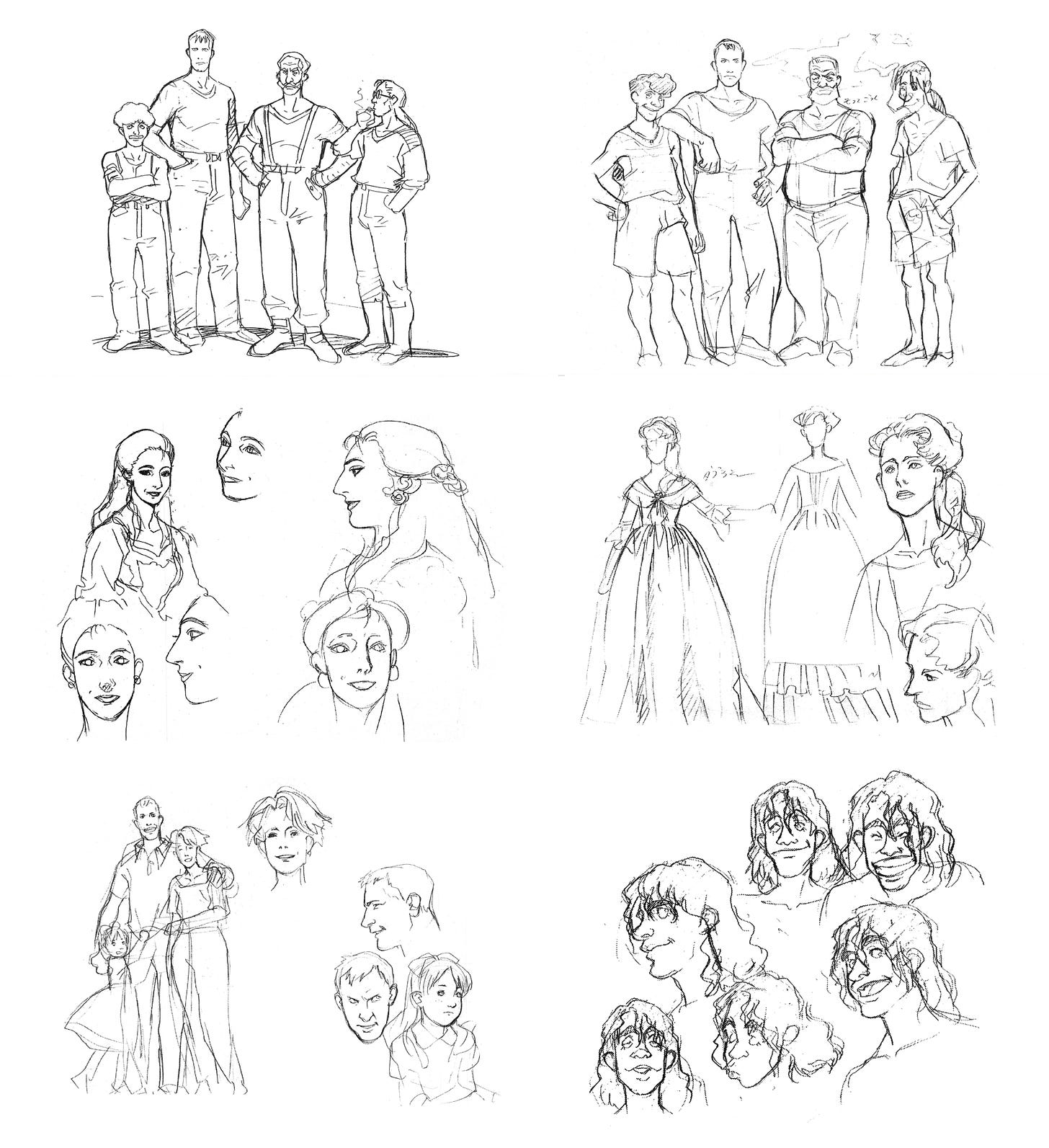

Kon filled a few roles here: he drew layouts, designed most of the station’s Rococo interiors and sketched the rough, preliminary character designs. Although he had no screenwriting experience, he was handpicked by Otomo for that job as well. The reason was a “shortage of manpower in the anime industry,” Kon said. There simply weren’t enough skilled writers to go around.5

His mostly straight adaptation of Otomo’s manga ran into a problem: the story was simplistic. The Otomo piece looked cool, and it had interesting ideas, but it was too slight to support a mid-length film. As Morimoto said:

Up to around the third draft of the scenario, we had a methodology that was fairly faithful to the original. It was a story about entering a haunted house and searching … but with that, sure enough, it’s nothing more than a series of surprises in which the experience there is unusual in some way. … The scenarist Kon, too, began to say that it wasn’t good.

They decided to give the story more emotional depth by developing Heinz, a character on the rescue team. Kon viewed the opera singer Eva as the true protagonist of the film — but Heinz became a second lead. “The more he investigates, the more he is in fact investigating himself,” Morimoto said.

A strong psychological thriller element came into Magnetic Rose, as Heinz (and his partner Miguel, for that matter) entered a fight between fantasy and the real world. It intrigued Kon and helped to get the film on track. “One could say that this is where my interest in the motif of mixing reality and illusion began,” he later admitted.

The opera theme was another deviation from the manga — although it was Otomo who came up with that one.

Yoko Kanno insisted on using Madama Butterfly for the score, but Otomo was hesitant at first, calling it Orientalist and too famous. When they recorded the music at the Dvořák Hall in Prague, though, he started to feel that Kanno’s intuition had been right.

“Initially,” Morimoto said, “the orchestral staff saw tiny Ms. Kanno and looked at her like, ‘Where’d the kid come from?’ But once they opened their sheet music and performed the grimly arranged aria from Madama Butterfly, the way they viewed and treated her changed to that of respect.”

Morimoto drew the rough storyboard for Magnetic Rose, calling it a struggle. He structured the film around the contrast of prettiness and ornament with filth and decay. There’s rubble and Rococo, and the Rococo peels away as the film goes on. He said that “the backgrounds also become symbolic in that way,” leading us inside Eva’s mind.

As Morimoto storyboarded, the team at Studio 4°C did the design and layouts. Kon and the artists adopted the language of live-action cinema to describe shots — using lens terminology and keeping perspectives realistic. Otomo felt that it just made sense:

At first glance, using a lens seems bothersome, but when you’re getting the background drawn or directing, it’s remarkably easy. Use a telephoto lens here. Telephoto, that’s why the depth-of-field is shallow. That’s why the background is blurry. Having done that, conversely, the character stands out… That alone makes for clear direction.

In general, realism was the order of the day on Magnetic Rose. The characters and environments are complex, and the acting is closer to real-world motion than most anime films of that time. Morimoto felt that the sci-fi setting demanded “a sense of presence that this person is alive, or that this building is standing.” There needed to be weight and subtle detail to make us believe in the unbelievable things we see.

A good deal of this vision was carried out by Toshiyuki Inoue, the film’s animation director and character designer. Like Kon, he came from Run, Melos! — another piece of anime hyperrealism. He’d been a main animator there. This time, he was even higher up and was essential to setting the style. As Inoue said:

… I ended up entering while I was extremely influenced by the characters of Melos. In the case of Melos, in particular, they were Greek, so as I went along, the noses rapidly came to be prominent. Maybe because of that, it seems like the characters I drew in the initial stages [of Magnetic Rose] all ended up having big noses. I was told that by everyone. Myself, I was thinking that wasn’t really so. Also, Melos had thick, solidly built limbs, and maybe because of that, the initial characters were all solidly built.

Inoue is a longtime fan of realist animation, yet Magnetic Rose kept pushing him further than he planned, or even wanted.

He tried to add more stylization — but found that only a “total commitment to realism” in the designs seemed to work. The cast is lightly caricatured, yet far closer to human proportions than most animation goes. That led to problems for the animators, who dedicated a ton of time to figuring out how to make such realistic characters move. It was a serious challenge, and Inoue wished it’d been simpler.

“[J]ust as the characters are realistic,” he said, “no matter what, the acting came to be likewise and conventional anime-ish movements were no longer usable.”

In recent years, Inoue has tweeted about the complex process of managing this film’s animation. Even though layout artists like Kon and Hiroyuki Okiura (Melos) were doing phenomenal work, and even though the key animators were aces from Akira and Melos and Ghibli, there were still problems. Inoue ended up doing major corrections to scenes throughout the film.

There was also the trouble of Rococo. It’s part of Otomo’s original manga: an impossibly decorated manor, done up all in poor taste. Inoue said that Art Deco would’ve been preferable, since he felt it looked nicer and was easier to draw. “Even Mr. Kon was saying, ‘I’m now fed up with Rococo,’ ” Inoue remembered.

Despite running just 40 minutes, this was a hard project. “Because of all the work, we called Magnetic Rose a work magnet,” Morimoto said. It was a new experience for many on the team, and done with technology we can hardly imagine now. Most of the CG shots were created on a Macintosh Quadra 950 with 256 megabytes of RAM. A budget smartphone today easily has a dozen times more.

As with any project this taxing, there were regrets. Kon cringed for years at Heinz’s line, “Memories aren’t a way to escape!” The wording was too on-the-nose for him — it pained him to hear it reused across Memories’ promo campaign. And Morimoto felt that, for all the film’s realism, it didn’t quite nail the sense of being there that he wanted.

It also wasn’t a hit. Otomo consciously aimed Memories at a more international audience than Akira had been, inspired by that film’s overseas success. But this wasn’t another Akira. “I heard that it was quite a failure at the box office,” Kon said, “and there were rumors that the attempt to sell it at a high price overseas backfired and there were no takers.”

Still, it’s easy, and maybe even for the best, to write this stuff off when watching Magnetic Rose. The film holds its own as an anime classic — a wildly ambitious, truly unique piece of work. When Otomo saw Memories at a Tokyo film festival in 1995, screened beside Macross Plus and Ghost in the Shell, he felt that Japanese animation was entering a bold new era. Which was true.

Kon was inspired to pursue directing thanks to his screenwriting job on Magnetic Rose. He kept exploring its themes across most of his work, and even reused parts of the story of Miguel and Heinz outright in Paranoia Agent. If there’s any decisive starting point to Kon-the-director, Magnetic Rose is probably it.

It’s a mistake to over-credit any single person for this film, though. The reality is that it was a team effort — no one auteur defined Magnetic Rose. It was more like a group of auteur-level talents, in their respective fields, getting together and making a movie. Morimoto said, “Even when we had a clash of opinions, it was interesting.”

If you’ve never seen it before, Magnetic Rose (and the whole Memories anthology) is free on Tubi in the United States. It’s absolutely worth the time.

Today’s issue was made possible by the animation historian Toadette, who helped us by translating chunks of the book The Memory of Memories (1996) — our main source today. Check out Toadette’s blog and YouTube channel for more research into obscure animation.

2: Newsbits

We lost Ippei Kuri (83), who co-founded the anime studio Tatsunoko in 1962.

In Japan, Hayao Miyazaki’s final film The Boy and the Heron (previously How Do You Live) became a smash hit despite zero pre-release marketing. Its opening weekend was Ghibli’s biggest to date. There’s serious buzz in the press and online.

Meanwhile, in America, the new translation of Miyazaki’s graphic novel Shuna’s Journey (1983) won an Eisner.

In China, the historical feature Chang’an is a blockbuster. This weekend, it passed 1.2 billion yuan (around $167 million) after its debut on July 8. Even Douban users like it. The film is about two Tang-era poets, and it’s led to a surge of interest in ancient Chinese poetry — and a sold-out book of poems tied to the film.

Also in China, there’s a teaser for the third entry in the White Snake movie series. It’s due out in 2024.

The Canadian software producer Toon Boom was acquired by an investment firm in New York — a move met with trepidation in America’s animation industry.

Another from Japan: director Koji Yamamura has a CG virtual reality film called My Inner Ear Quartet, and it looks bizarre.

In Colombia, a program called “Project I” seeks to reduce youth unemployment and solve the animation labor shortage at the same time — by offering free animation training and infrastructure to young people. It’s a big deal, with a lot of international backing.

An exciting American story: a group of animation workers in Puerto Rico voted to join The Animation Guild. It’s reportedly “the first time that TAG has organized outside of the continental United States.”

Lastly, during our break, Disney+ launched the pan-African series Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire. You can feel the passion and excitement in it — and the fresh perspectives. From Egypt to Nigeria to South Africa, the continent’s animation is coming into its own. It’s a thrill to watch.

See you again soon!

From the interview with Morimoto on the Memories Blu-ray from Discotek Media, which we cite throughout.

From the book The Memory of Memories, also used throughout. Translation by Toadette.

A Farewell to Arms was later animated in Otomo’s anthology Short Peace — where it turned out very well.

From the NHK featurette on the making of Magnetic Rose, included on the Discotek Media Blu-ray (also watchable here).

We relied quite a bit on Kon’s old site for today’s issue, referring to pages here, here, here, here, here and here. Kon was scheduled to have an interview in The Memory of Memories, too, but lost it after he yelled at the editor for misspelling his name. As a result, details about his involvement in Magnetic Rose are trickier to find.

I finally watched Run, Melos! and really liked it. This is now on my list.

Gosh I remember renting Memories on video cassette from Blockbusters and absolutely loving it. Not having seen anything like it animation-wise before, I was enthralled. Also, I’m glad that they kept Puccini’s music as even though Madam Butterfly is definitely orientalist, that aria is phenomenal and really fits with the film.