Happy Sunday! We’re back with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the lineup today:

1️⃣ The story of The Snowman (1982), directed by Dianne Jackson.

2️⃣ Animation news around the world.

If you’re just finding us, you can sign up to receive our newsletter in your inbox:

With that, here we go!

1: Crayons and kebab skewers

As TV gets replaced by streaming, the old restrictions of broadcasting fade away. Those restrictions were arbitrary and weird, but they forced art into shapes that came to feel familiar. Half-hour episodes. Prime-time sitcoms. Late-night TV.

And animated Christmas specials, like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, produced for a small fortune and designed to rerun each year.

These shapes are wobbly now — there are different pressures at play. But animated Christmas specials, at least, are still a big deal in the United Kingdom. Wonderful new ones like Zog (2018) and The Tiger Who Came to Tea (2019) appear each year, produced by studios like Magic Light Pictures and Lupus Films.

It’s part of a tradition, and not just a broadcasting one. In a way, it goes back to The Snowman.

The Snowman first aired in 1982. In the UK, it continues to rerun every Christmas. And it’s more than a fun novelty: it’s gorgeous, ambitious and deeply felt. In ‘83, it got an Oscar nomination. In ‘03, a major Japanese festival named it one of the best works of animation ever made. The great Yoichi Kotabe and Reiko Okuyama were on that jury — both placed it in their top 20, beside Frédéric Back’s The Man Who Planted Trees.1

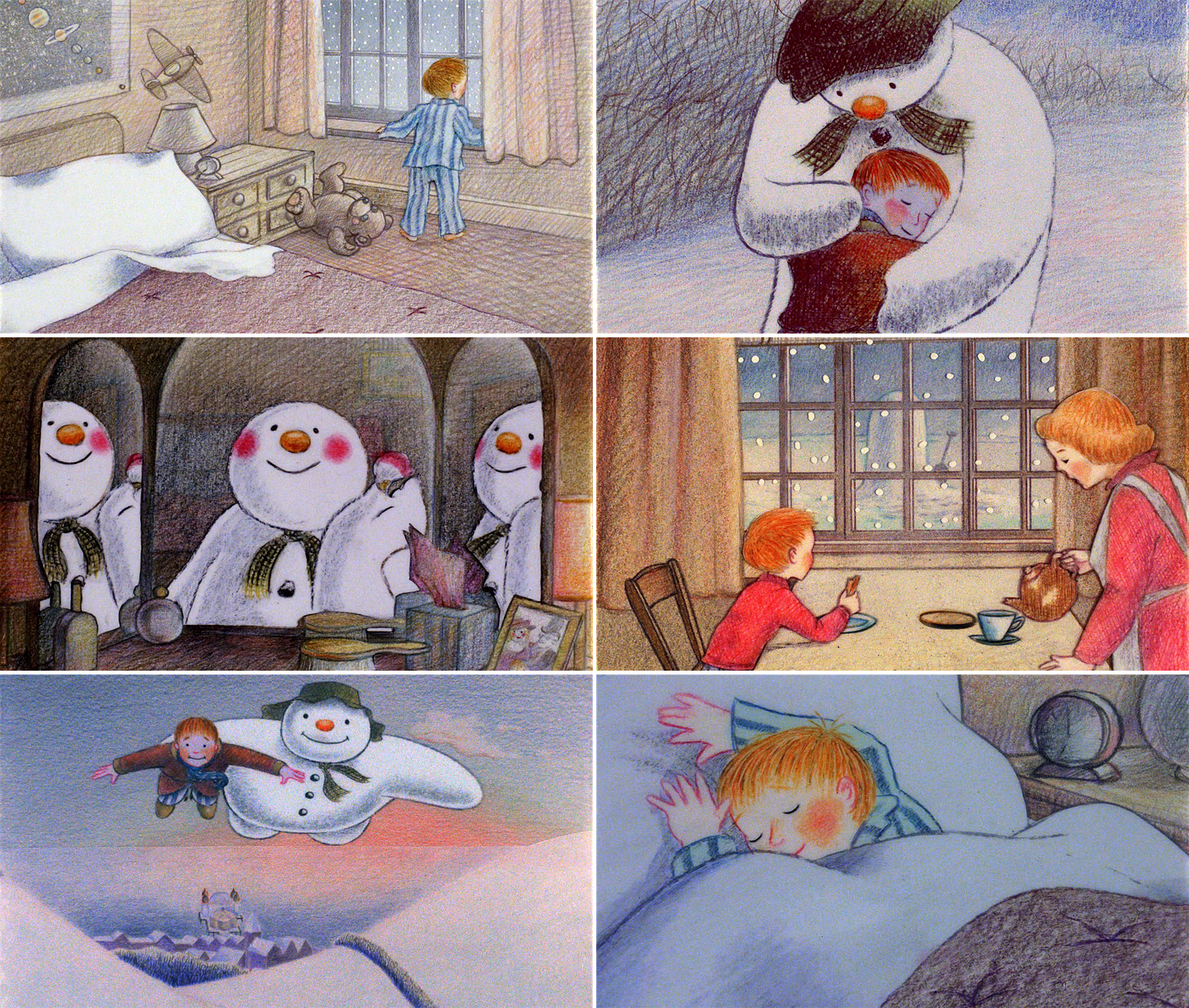

Back’s animation inspired The Snowman — it’s a richly textured show, done in 2D but not in the Disney style.2 It adapts a 1978 book by Raymond Briggs, a children’s story about a boy and a living snowman. Briggs illustrated his book in colored pencil. The animation team wanted to make those illustrations move.

The Snowman’s director, Dianne Jackson, once recalled, “[Artist] Lyn Rockley and I stayed up until 2 a.m. one night, until we solved the technical problem of rendering that ‘crayon’ look so special to Raymond Briggs’s original.”3 This long night would be one of many.

Dianne Jackson had been in the industry since the ‘60s, when she animated on Yellow Submarine. That film’s director, George Dunning, was “a marvelous mentor to her, inspiring in her work a maturity and a style that was to become her own.”4

“George never told you what to do,” Jackson remembered, “but rather let you express your own vision.”

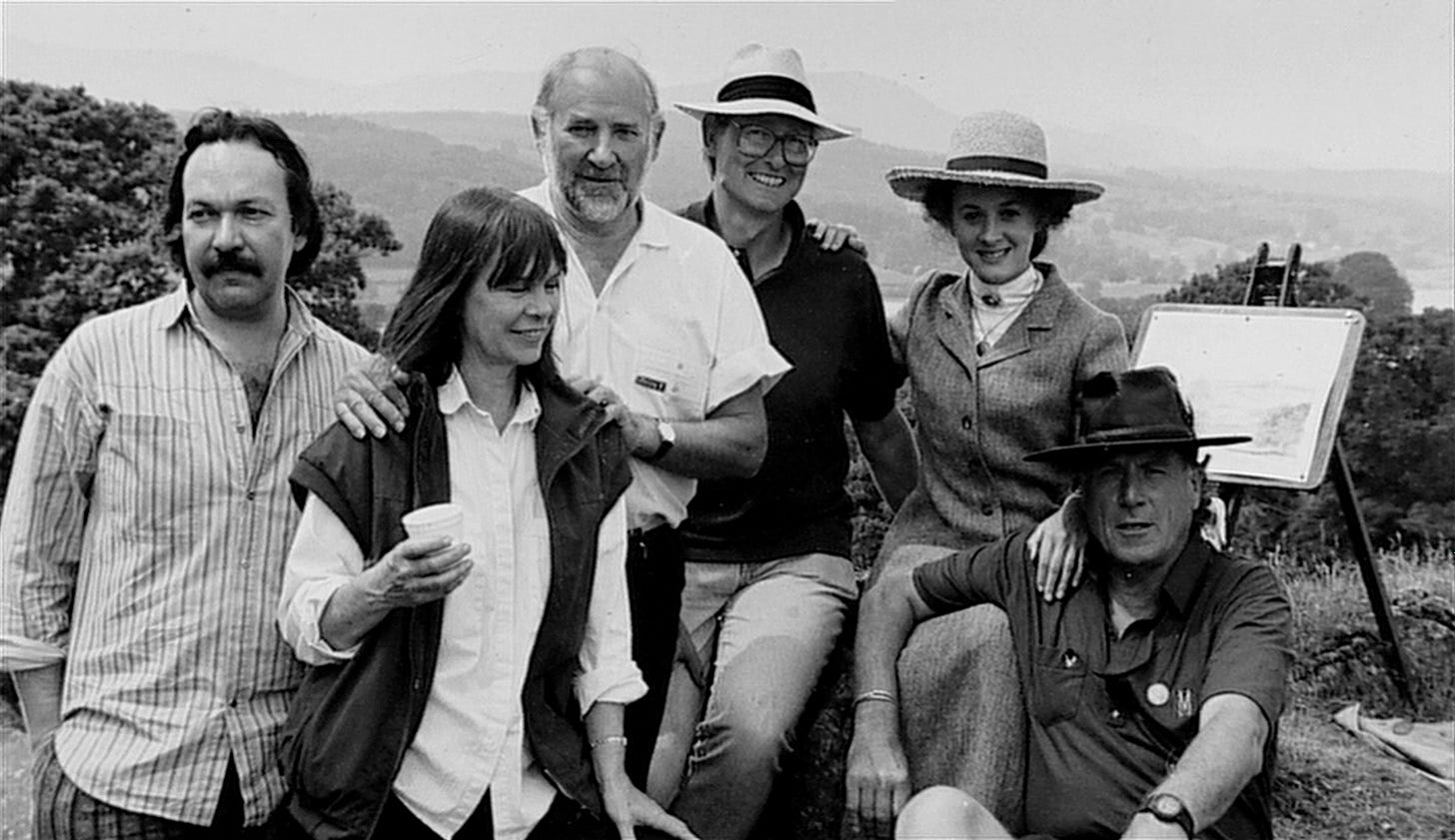

She worked mostly at Dunning’s London studio TVC — where she took on The Snowman in the early ‘80s. By that point, though, Dunning himself had passed away. In charge was his old colleague John Coates, a producer with a “tremendously laid-back, happy, easy-going approach.” He was good at business and nurturing to talent.5

The Snowman was Coates’ big gamble. A TVC animator had shown him Briggs’ book — and it looked like an opportunity. As Coates said:

From a creative standpoint, the history of TVC up to the time of George’s death was wholly concerned with things he did. After he had gone, I sat in my office wondering whether the phone would ever ring again — but it did, and we continued making commercials. And the more I thought about it, the more I wanted to make something we owned. We had become too dependent on the telephone. If it didn’t ring for a month, we worried! I wanted to make something which would provide us with an income, and The Snowman was our first attempt.

Coates decided to pitch his idea to the newly-minted Channel 4. So, he assigned TVC artists Hilary Audus and Joanna Harrison to create an “animatic.” They bought maybe a dozen copies of Briggs’ book, a wordless graphic novel, and cut its panels into an animated storyboard.6

Harrison and Audus added things as they went, too. The original wasn’t a Christmas story — but they put in a visit to Santa Claus. Elsewhere, they switched a scene in a car to a motorcycle ride. “I was a motorcyclist at the time,” said Audus, “so we thought it’d be very much nicer if the snowman and James got on the back of a motorcycle, because then you’re actually in communication with the countryside.”

Coupled with a temp score by composer Howard Blake, who brought along his soon-to-be-iconic song Walking in the Air, the pitch animatic was gold.

The first pick to direct was Jimmy Murakami, a Japanese-American animator who’d set up a studio in Ireland. He didn’t love the idea of doing a children’s special, though. “It wasn’t my cup of tea so I became supervising director,” Murakami said. Which is where Dianne Jackson came in.

“After a false start, [Coates] chose Jackson, who had to that point directed nothing more ambitious than short television commercials,” recalled one observer from Channel 4.

Jackson was around 40 at the time, and an experienced talent in animation — even if she hadn’t done longer work. “Genius” was the word Joanna Harrison used to describe her: “She was an incredible animator and draftsperson. She was fantastic.”7

It was Jackson’s job to storyboard The Snowman, stretching the initial 7-minute animatic into a half-hour show. But it was tricky. According to Coates’ biographer, Jackson’s first pass was a misfire: “too spiritual and serious for his tastes,” too different from the animatic.

Murakami came in to review her work, Jackson took the feedback and the trouble was resolved. She followed the animatic more closely, and Coates was sold. Still, it was a huge drawing task. Briggs remembered visiting TVC during The Snowman to find “a great room ... lined from edge to edge and floor to ceiling with the storyboard.”

Jackson’s vision as a director was specific, but she was no tyrant. The Snowman’s composer wrote that she “rapidly proved to be an inspirational director whom everybody loved working for.” Her philosophy was, in a sense, similar to what she’d experienced with George Dunning. Here’s her take on the process:

... I storyboard the film, and then I think which animator would best express that sequence. They don’t necessarily have to know the main thought that’s in the back of my head. In fact, I don’t want them to — I want them to be intuitive.

The composer saw The Snowman’s final storyboard in April 1982 and wrote his score to follow it. From there, the animators had to sync their work to the music. It was textbook “Mickey Mousing”: what you hear is what you see.8 A tired style back then, but they breathed life into it. Most importantly, the melancholy song for the flight of the snowman and the boy, Walking in the Air, was an evocative clash with the imagery.

Sequences were divided up between the key animators (Jackson drew the snowman party toward the end). That flying sequence went to the animator couple Steve Weston and Robin White. It’s the centerpiece of the film, and a technical showcase full of complex camera turns. Coates was adamant that no rotoscoping was involved.

“No — no!” he said when asked about it. “I brought Steve and his young lady over from Canada to animate that sequence. It is very nicely done — even to turning the pier in perspective.”

Coates believed in traditional animation. He resisted the pull of computers, even though they were gaining in the business. It would’ve been possible to use 3D renders for the flight sequence, but “the film would have lost an awful lot of its charm and ‘something special’ feeling” along the way, Coates said. It’s a little rough-hewn, and that adds to its handcrafted feel.

Still, though, it was brutal and counterintuitive work to capture Briggs’ style in motion. That was especially true for the rendering artists, who turned the animators’ sketches into the art we know today.

The back of each cel was painted. Meanwhile, the front was rendered in wax crayon — scratched and detailed with a “kebab stick,” according to art director Jill Brooks.9 She’d come over from Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982) and was key to the rendering process. As she remembered it, each frame took around 45 minutes to finish.

The artists used children’s crayons that weren’t designed for animation. Held for long hours, they grew warm and soft in the hand, and had to be cycled in and out of a refrigerator to keep the consistency right. The tight schedule left people at their desks through the night. “I mean, seven days a week. I mean, 20 hours a day, sometimes,” Jackson said.

In Brooks’ words:

I remember one of the girls couldn’t actually take an all-nighter and she lay on the floor, groaning. ... We yelled out of the window, because they used to clear the bins from the restaurants at 4 o’clock in the morning, and we would shout out of the window and ask if there’s anybody who can render out there. [laughs]

It took between 60 and 100 people to make this show on time. TVC could hire so many because real money went into the project. Channel 4 put up £100,000 at the start, filled out by £75,000 from book publisher Hamish Hamilton. The final cost has been estimated as high as £500,000 (£1.7 million in today’s money). Coates’ biographer said that he “re-mortgaged his house for £50,000 to finish the film.”

At the time, the cost was outrageous for any British TV production. TVC went into debt — as one person at the studio later admitted, “We had put every penny we had into it.” The Snowman took three years to earn back its costs. After that, though, it became a profit monster.10

It’s not often mentioned that The Snowman had a slow start. Its Channel 4 premiere on December 26, 1982, got good reviews but low ratings. In July 1983, a snide newspaper columnist saw that Coates was due to appear on TV, and was aghast:

What a ragbag of a programme Granada’s Some You Win, tonight, appears to be. Flops like salesman Geoff O’Neill who has written 521 songs and never had one published. Successes like the Thompson Twins singing their latest hit, and John Coates. John who? He’s on the show because he produced Channel 4’s award-winning film The Snowman. Remember? Neither do I.11

That writer spoke a few months too soon. The next rerun in December 1983 would transform The Snowman into a cultural event. Author Clare Kitson noted that “word had got round and the audience increased massively.” The special took off.

What TVC had made was experimental, artful and a little sad — The Snowman shares more with Frédéric Back’s Crac (1981) than with Frosty the Snowman. Yet it became a Christmas tradition in the UK. In the process, it started an animation tradition, too.

TVC saw huge profits from it. Once, the studio reportedly stayed open for “an entire year on Snowman revenue” alone. And so Coates and his team kept following the same path of ambition and artistry. They soon did the Briggs adaptation When the Wind Blows (1986), with Murakami in the director’s seat and Jackson as a staff artist.12

Jackson herself moved up as a director until she led The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends (premiered 1992). It’s a classic, animated beautifully in Beatrix Potter’s style, and it was then “the most expensive animation project ever undertaken in the United Kingdom.”13 The series was colossally popular.

Coates produced those two and many more. Artists from The Snowman were in his stable through it all. When he died in 2012, he was still working on a sequel to The Snowman (directed by Hilary Audus) and an animated version of Briggs’ Ethel & Ernest (directed by Snowman animator Roger Mainwood). Both were released by Lupus Films.

These projects paired veterans from TVC with new generations of artists. Since then, it’s kept happening. Joanna Harrison, for example, wrote Lupus’s Tiger Who Came to Tea and its upcoming Mog’s Christmas. These specials are frequently great, sharing the warm, quiet feeling that work like Jackson’s had in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Animated specials aren’t the money-printing machines they used to be. The streaming era has its own rules. But, at least in the UK, people keep showing up to watch — and the quality and inspiration persist. Projects like The Tiger Who Came to Tea represent a holiday tradition, but also a living, breathing artistic one that, more than 40 years later, attests to the enduring magic of The Snowman.

2: Newsbits

In America, The Boy and the Heron placed third at the box office this weekend, climbing up to $23.1 million. As Catsuka points out, that’s the best lifetime performance Ghibli’s ever had in the States.

Meanwhile, the film saw far and away the biggest opening weekend for a theatrical anime feature in Russia. Interestingly, The Boy and the Heron’s distributor released it in three versions: two separate dubs (one for parents with children, one for hardcore fans) and a Japanese-language edition with subtitles.

A rare American short, Glago’s Guest by Chris Williams (Big Hero 6), has emerged on YouTube in full.

Check out Catsuka’s preview of the French event Cartoon Movie. It includes a peek at the next film by Patrick Imbert, director of The Summit of the Gods.

In Madagascar, the long-running festival Madagascourt gave its top animation prize to Indlela Yokuphila: The Soul’s Journey — a film whose lush visuals call to mind Cartoon Saloon. Watch it on YouTube with subtitles.

One more Boy and the Heron story: in Japan, a new documentary called 2,399 Days With Ghibli and Miyazaki covers the film’s creation.

Cartoon Brew has a sizable interview with Spanish director Pablo Berger, all about his feature-length Robot Dreams. (Also, lots of production art.)

In America, showrunner Olan Rogers (Final Space) posted the 28-minute pilot for his indie series Godspeed. He funded it via Kickstarter, and its release ties into a second Kickstarter campaign to continue the project.

In Japan, a new report shows that the anime industry earned 2.92 trillion yen in 2022 — more than $20 billion. Half of that revenue came from outside Japan.

Lastly, we looked at the almost 60-year history of Hayao Miyazaki’s image boards, arguably the engine of his creative process.

See you again soon!

In her biography John Coates: The Man Who Built The Snowman (2011), author Marie Beardmore points out that TVC was consciously taking from Back’s work. His film Crac won the Oscar in early 1982. We use Beardmore’s book as a source throughout.

From Peter Cowie’s article 35 Years of TVC London, published in the 1993 Variety International Film Guide. We reference it several times.

From Dianne Jackson’s obituary in The Independent, written by Paul Madden of Channel 4. Referenced multiple times.

This is how Raymond Briggs characterized John Coates in The Independent (December 9, 2007). “John is a great lunching man,” Briggs wrote. “Not just with me, but with everybody under the sun. … He’s the most genial man I have ever met.”

As explained in the documentary Snow Business: The Story of The Snowman, used a few times.

From the documentary The Snowman: The Film That Changed Christmas, the source for several key quotes.

Clare Kitson makes this point about “Mickey Mousing” in her book British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor, a valuable source for a few details today.

The rendering process was explained in The Snowman: The Film That Changed Christmas, this interview with Roger Mainwood and this interview in The Mirror.

See The Evening Standard (December 12, 1991).

See the Manchester Evening News (July 30, 1983).

The book The Multi-Media Melting Pot: Marketing When the Wind Blows claims that the early stages of When the Wind Blows actually coincided with The Snowman’s production. Many staffers, including Steve Weston, worked on both.

See The Camarillo Star (April 11, 1993).

Really enjoyed this article, thank you!

I just wanted to point out a small correction: It says "Briggs illustrated his book in pencil and crayon". He actually illustrated it in just 'pencil crayon' which is what we call coloured pencils in the UK.

It's true they did use wax crayon for the animation though, because they could achieve a similar look to coloured pencils, except it was possible to draw it on cells. (I heard this info at a talk from Lupus films at Manchester Animation Festival last year 🙂)

Great article! Thank you!