Welcome! It’s a new Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing:

1) On The Order to Stop Construction (1987) by Katsuhiro Otomo.

2) Animation news.

Now, here we go!

1 – A study period

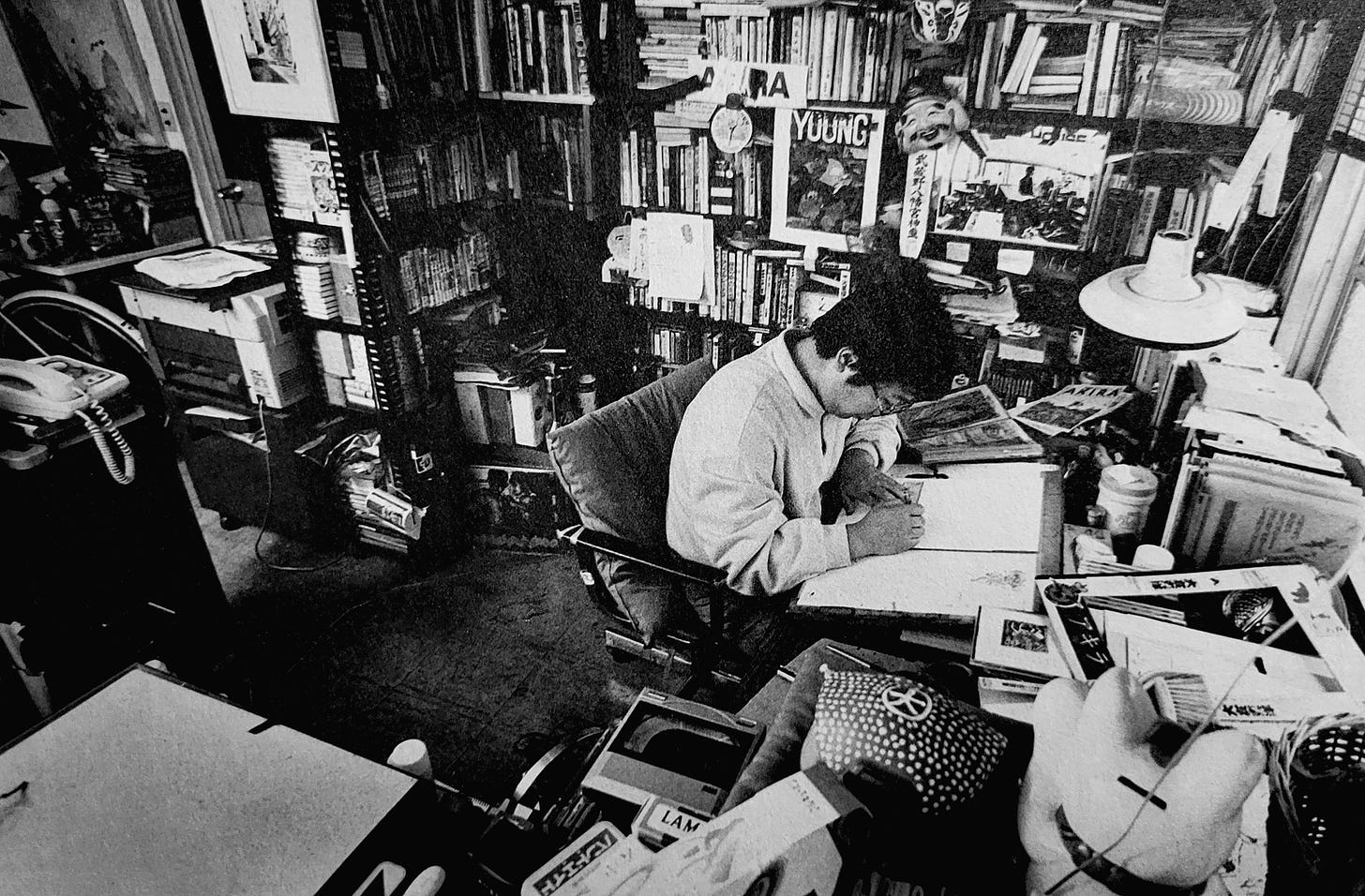

When Akira appeared in 1988, it changed things for anime. It was an international hit — in theaters, and especially on video. The artist behind it, Katsuhiro Otomo, had never made an animated feature before. He was suddenly a major director.

Even so, Akira came from somewhere. Otomo started it as a manga series, which had already made him famous. More importantly, he had a history with anime. Akira was his first animated feature — but he’d made a short film. A short film that had paved the way for him. In key respects, it’s the proto-Akira.

Its title is The Order to Stop Construction (1987). Even in Japan, only a core group has seen it. Yet it was here that Otomo figured out how to make animated movies. It was his proving ground, and it remains a great film in its own right.

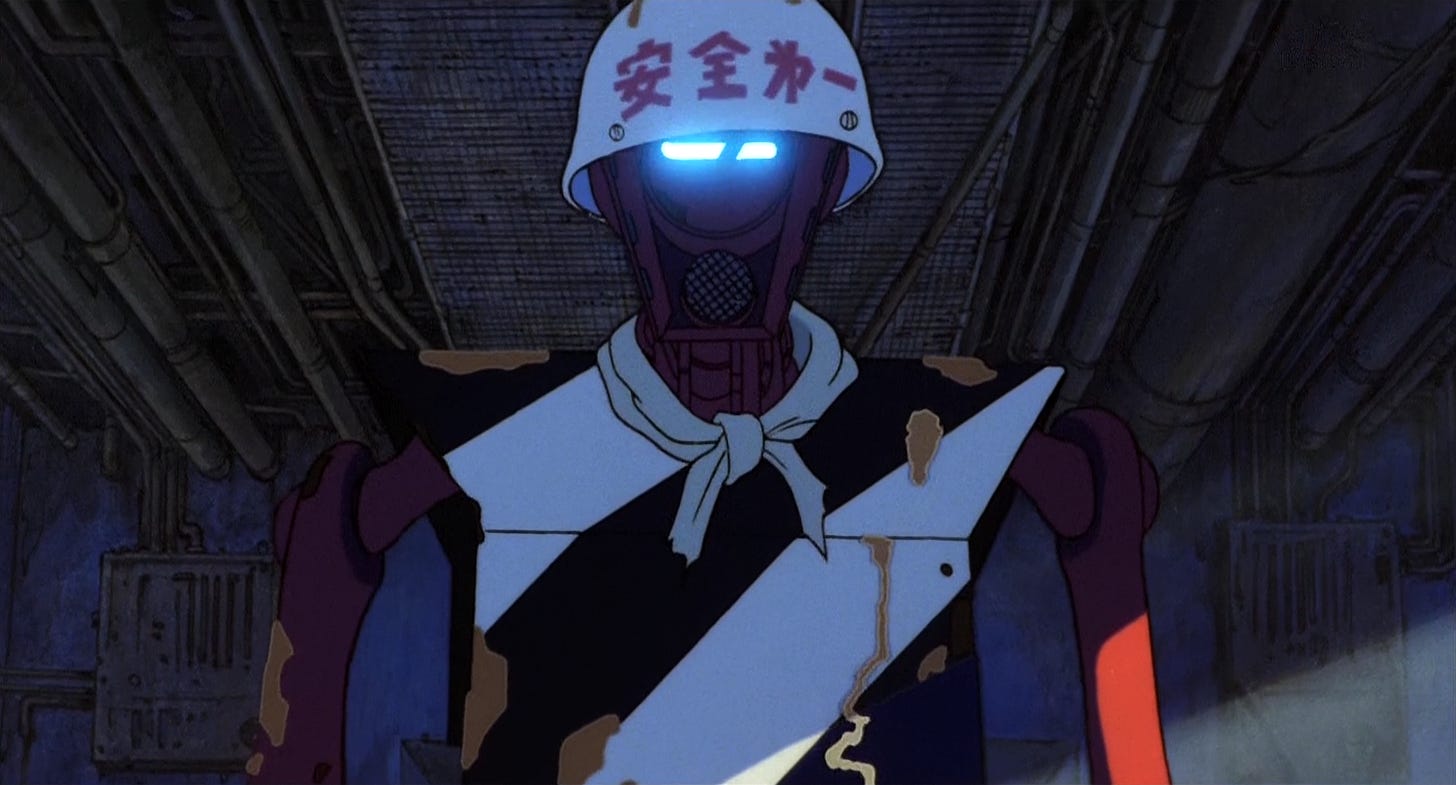

The Order to Stop Construction is about a robot construction crew gone mad. It’s a satire that doubles as a tale of survival. One critic called it “a pitch-black comic melding of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey,” which isn’t far off the mark.1

These robots are trying to build a Babel-like compound in a jungle, with poor results. It’s all chaos and destruction. When a human foreman arrives to end the project, the robots refuse. He’s stuck in a situation that’s at once dark, funny and harrowing. Through him, we enter the world of the construction zone, a deranged byproduct of corporate greed.

The Order to Stop Construction was Otomo’s first time directing an animated film. He began with little knowledge of the medium, and had to work “while learning” from his team, he said.2 But it’s an assured piece with a lot to say, and it’s very well built, from the scenes of the robots running wild (watch) to the ambush toward the end (watch).

Before this film, Otomo had only done a little work in anime — landing a character design role on the popular Harmagedon (1983). That experience made him curious about taking the wheel himself. Like he put it:

Around the time I worked on [Harmagedon], I also visited the studio while the anime was in production. Watching them work made me feel, “Maybe I can do this by myself?” So, that was the beginning, I suppose.

Harmagedon’s director, Rintaro, had hired him based on his early manga stories and a book cover he’d drawn.3 Already, Otomo’s stuff was different, and Rintaro felt that it could bring a new style to anime. The drawings were gritty, kinetic, realistic. So, Otomo found himself cycling back and forth to the Tokyo studio to design characters.

In 1984, his big chance arrived. At the studio Madhouse, Rintaro became the producer of an anthology film called Neo Tokyo.4 Otomo was asked by the head of Madhouse to direct a short for it. Rintaro wanted him, too: he saw “a great knack for cinema” in Otomo’s self-funded, live-action film Give Me a Gun, Give Me Freedom (1982).

Otomo accepted the offer. “I thought I could do it if it was a 15 minute piece,” he recalled.

At first, the plan was an anime anthology based on stories by Taku Mayumura, a sci-fi author. Otomo picked The Order to Stop Construction (1967). “It’s a strange story about going deep into the jungle to stop construction work, [and] it’s not complicated,” he said. It was also short enough for his needs.

Neo Tokyo was a messy project, though. The other director intended to work alongside Otomo, Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell), passed on the job and was replaced. And the other films drifted from the Mayumura theme, or abandoned it altogether. “I was the only one left adapting fiction,” Otomo said. He stayed fairly true to the story.

Filmmaking has always been close to Otomo — that’s clear even in his manga. He’s cited the theories of Eisenstein (among others) as influences. Naoki Urasawa of Monster fame said this about Otomo’s pre-Akira manga from the ‘70s:

It was different from the conventional rhythm in Japanese manga and more like something lifted from Kubrick or Peckinpah — the stuff that we considered hip, right there in a manga.

Despite that background, though, Otomo was coming to anime very green. This caused problems for him. “I was asked to draw a storyboard,” he later wrote, “but I’d never drawn a storyboard before and had no idea what to do.”5

His solution was to look to another filmmaker he admired: Hayao Miyazaki.

Miyazaki had hit Otomo’s radar with Future Boy Conan (1978) and especially The Castle of Cagliostro (1979). The filmmaking of those projects deeply impressed him. In 1980, Miyazaki followed Cagliostro with two final TV episodes of Lupin the 3rd, and Otomo was paying attention.

To learn storyboarding on The Order to Stop Construction, Otomo wanted to study Miyazaki’s storyboards for Thieves Love the Peace — the second of those two Lupin the 3rd episodes. There was a complication, though. As Otomo remembered:

... I really wanted to get the storyboards, but, after all, the production site was Madhouse. I didn’t think it would be possible to ask people from another studio to give me storyboards, so I substituted by watching the videotape over and over again. I think it’s fair to say that I learned a considerable part of how to create animation from this video, such as the number of shots (katto-su) and the cinematography and editing (katto-wari). I directed The Order to Stop Construction while studying the composition of Thieves Love the Peace.

Miyazaki-san has a straightforward approach, doesn’t he? Other people push forward with flair or brute force, and it may be eye-catching, but, in the end, the work is off-balance when viewed as a whole. … Even though the number of shots in Thieves Love the Peace is so large, the scenes are tightly organized, so there are no unnecessary shots at all. As a result, even though the content is very elaborate, it isn’t difficult to understand. Moreover, the layouts are quite good, and the picture itself is tangible and easily understood. It looks natural, and it contains more information than you need to keep track of. Usually, when it comes to TV animation, there are numerous bust shots with only a ceiling as the background. … Of course, Miyazaki-san’s works aren’t without such scenes, but they don’t stand out because of the well-balanced composition [of the works].

What Otomo wrote about Thieves Love the Peace goes also for The Order to Stop Construction. He visibly borrowed filmmaking ideas from Miyazaki, plus his use of space — the sense that this world is three-dimensional. Even imagery from the episode turns up. A number of shots, especially of the robots, call back to Miyazaki’s. It all helped to give Otomo’s film a very solid, immersive feel.

Thieves remained an influence on him. You can spot more of its visual and story elements in Akira. The famous Akira bike slide itself resembles a shot from Thieves, in which Inspector Zenigata does almost the same move on a red motorcycle. We just watch it from the opposite side.

Miyazaki has said that he hated making this episode. Returning to Lupin was “hell,” and he felt he was “just trotting out everything [he] had done before.”6 But Otomo saw more in it, and The Order to Stop Construction was his first step toward reverse-engineering its magic. In the end, Otomo was able to storyboard his film himself.

Watching and rewatching Thieves Love the Peace was just one part of Otomo’s education process. Rintaro chose to pair him with top artists: animators Takashi Nakamura and Koji Morimoto, and art director Takamura Mukuo. They helped a lot. So did Rintaro, who reportedly taught Otomo about the art of directing animation.

All of them came from Harmagedon — Morimoto remembered Otomo from that film. “I was observing [Otomo] from a distance,” he said. “[He was] hunched over [his] desk like this ... so close to the paper that I thought, ‘Is he asleep?’ ”

On The Order to Stop Construction, they grew friendly. “While [Morimoto was] doing key frames we talked about a lot of different things,” Otomo noted. Morimoto animated huge sections of the film — as did Nakamura, who defined the jittery movement of the head robot and drew moments like the final ambush.7 The size of the workload meant that “the pressure was tremendous,” according to Morimoto.

Only four key animators are in the credits, and most of the work was done by those two. Also involved, though, was Otomo himself. With Nakamura’s guidance, he learned to animate. Nakamura was a Disney fan — Otomo used books about Disney animation to study. He was a total beginner, and he made mistakes: his early tries were animated all “on ones,” which led to a chaotic look.8

But Otomo got better. In the final film, the scene where the main character spits out a metal nut was his work, among others. It surprised Morimoto. Otomo drew solid figures in his manga but used Disney-style deformations when he animated. The results were “extremely skillful,” Morimoto said (he took inspiration from their looseness). Later, on Akira, Otomo would correct a large number of shots himself.9

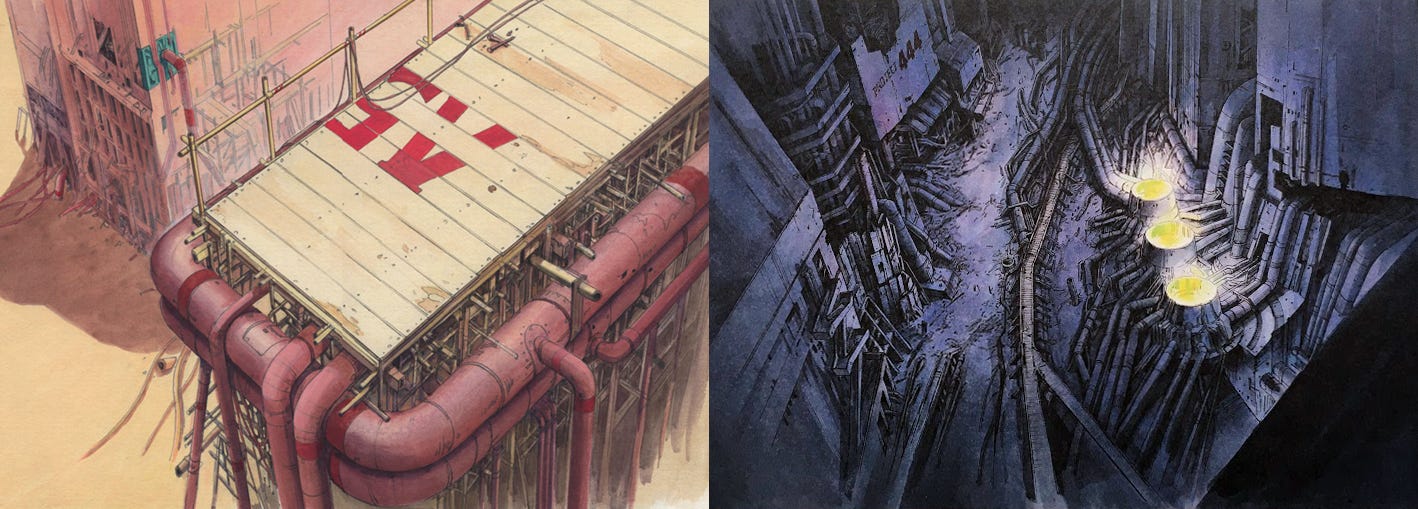

Besides the animation, a major aspect of The Order to Stop Construction is its detailed background art. This was Takamura Mukuo’s domain — he was among the best to work in anime backgrounds, on projects like Isao Takahata’s Gauche the Cellist (1982). His involvement made Otomo “very grateful.”

Getting this right was another struggle. Mukuo branched out, trying unusual things like the pink skies. Otomo, a specialist at environments, drew background sketches for the painting team and helped to establish the film’s hyperrealistic world. It’s not a cold, rigid realism: the backgrounds have a roughness. Pencil lines show up in the final art, as does the white of the page.10

By the time The Order to Stop Construction started, the Akira manga was well underway. Otomo juggled the two. Akira was serialized every other week, so he alternated: one week of work on Akira, one on the film. During it all, he continued cycling to Madhouse.

Otomo began The Order to Stop Construction in mid-1984, and Neo Tokyo as a whole wrapped in ‘85, after around a year. The public wouldn’t see any of it for several years more.11

Again, things were messy for this anthology. It’s “a long story,” as Otomo said.

According to Rintaro, Neo Tokyo was designed as a double bill with the little-known Time Stranger (1986), also adapted from Taku Mayumura’s work. Plans changed after a poor internal response to Neo Tokyo — specifically, investor Haruki Kadokawa wasn’t happy. The anthology was too out-there, he said. It was shelved.

Otomo called the project “fun,” but he had to move on, joining the anthology Robot Carnival (1987). Before that was done, he started the Akira movie, with Takashi Nakamura and Koji Morimoto in major roles. Neo Tokyo only had a festival debut in late ‘87 (months after Robot Carnival). Then it was dumped on video. A limited theatrical run followed in ‘89.

It created a weird situation. By the time the world saw what Otomo had learned, The Order to Stop Construction was already years old, and Akira was nearly done. The feature overshadowed its own origins. It was easy to think of Otomo as a filmmaker from nowhere.

But this obscure short has a place in anime history — maybe a massive one. Animator Toshiyuki Inoue (Akira) once suggested as much. The Order to Stop Construction was a “turning point,” he said. Madhouse was attempting to chart a new course in anime, and Otomo’s film, in many ways a learning project, had done it.

“In the end,” Inoue argued in the 2000s, “I think the starting point of the animation technique that everyone is aiming for today is clearly found in The Order to Stop Construction.”

2 – Newsbits

Richard Sherman (95) passed away. He was a veteran Disney songwriter from The Jungle Book, Mary Poppins and more.

Speaking of Miyazaki — in France, he and producer Toshio Suzuki appeared via a pre-recorded video at Cannes. The crowd loved it.

Italian animator Giulia Martinelli has wrapped the first season of her podcast Under the Onion Skin, a valuable collection of interviews with animators on the festival circuit. She tells us she’ll be at Annecy next month to record more for season 2.

The Treasure of Barracuda is a Spanish feature in development, pitched at the recent Cannes Film Market. It now has a distributor.

In China, artist Sadao Tsukioka (a veteran of Toei Doga’s early films) donated a massive illustrated scroll to Shaolin Temple. He created it over a period of months — it’s over 30 feet long.

In Japan, the Ghibli Museum is showcasing the layouts of The Boy and the Heron, and Oricon has quite a few photos.

Also in Italy: the story of the animated sequences in Liberato’s Secret, a hybrid documentary. Intriguing details about the “very logistical” problems involved, and the filmmaking workarounds used to solve them.

There’s a trailer for Dolores, the stop-motion horror film by El Taller del Chucho of Mexico. The studio previously animated on Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio.

In France, Annecy revealed its WIP showcase for 2024. On the feature film list are A Story About Fire by Shanghai Animation Film Studio and Hyakuemu by Kenji Iwaisawa, known for On-Gaku. (Iwaisawa seems to have two features underway right now — the other, Hina Is Beautiful, may come out after this one.)

Lastly, we had a conversation with a veteran of British animation — Tony White. He revealed inside details about London’s animation scene of the ‘70s, from his time at Halas & Batchelor (Animal Farm) to Richard Williams Animation.

See you again soon!

See Imagi-Movies (Summer 1995).

See this article by Cinema Today, a key source. We also looked at this article.

These details (and many others throughout the article) come from the book Plus Madhouse 04: Rintaro. Thanks to Toadette for this one.

Neo Tokyo is the anthology’s American title. Its original one more closely translates as Labyrinth Tales. (The 1984 detail comes from this tweet by researcher Junya Suzuki.)

All of the quotes about Otomo’s use of Thieves Love the Peace come from his essay in the booklet for the Ghibli ga Ippai LaserDisc collection from the ‘90s. Our thanks to Justin R. Hamrick for the help with this one.

From Starting Point 1979–1996 (“Miyazaki on His Own Works”).

Inoue confirmed Nakamura as the artist of the ambush sequence on Twitter.

For more details on Otomo’s animation for the film, see this article, this interview (and this one), plus the tweets here and here related to his 2021 talk about The Order to Stop Construction.

See Animage (September 1992), via Anim’Archive.

The point about Robot Carnival coming out first was made by Anime Style.

Ahh great article! It's funny... I fell in love with the short film anthologies from that period, Robot Carnival, Manie-Manie, Memories etc. and Construction Cancellation Order is definitely a highlight, but I didn't realise how crucial it was to Ōtomo himself learning animation. It's fascinating how the same names keep coming up - Rintarō, Miyazaki (pre-Ghibli), Nakamura, Oshii - this honestly tiny circle of artists influencing each other and in turn transforming pretty much the entire medium of animation. I wonder what an Oshii short in Manie-Manie would have been like.

Also! 'Construction' being finished with just four key animators is astonishing, honestly, especially in these days of gigantic lists of nigen and sakkans on every show. It's not exactly a low drawing count short.

Anyway I love that you keep writing about this period and those short film anthologies, I always pick up something new and it's great to see someone else appreciating them. Have you seen the more recent anthology 'Short Peace' (2013)? It's almost entirely CGI, but very effectively used; Ōtomo has a short film 'Combustible' with a unique style and 'A Farewell to Arms' also adapts one of his stories to a really compelling near future battle sequence. 'Possessions' is also really charming. I'd love to read some similar production anecdotes about those films if you ever came across any!

Brilliant work as always! Are the Hayao Miyazaki directed episodes of Lupin the 3rd Pt. 2 stand-alone or do I need to be familiar with the rest of the show to enjoy it? The only Lupin media I've seen are parts of the manga when the English rerelease came out a few years ago and Castle of Cagliostro.