When Rotoscoping Goes Very, Very Right

Plus: animation news worldwide.

Happy Sunday! And welcome to our new readers from Thursday’s public issue, which went far bigger than we ever expected. We hope you’ll enjoy what we do here.

On that note, our slate for today:

1️⃣ The art of rotoscoping in When the Day Breaks.

2️⃣ Animation news from around the world.

And now, we’re off!

1: Rotoscoping done right

At this point, Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbis are something like animation royalty. Their latest film, The Flying Sailor, is currently up for an Oscar — just like every other film they’ve co-directed to date. It’s a streak that reaches back to the ‘90s, beginning with the legendary When the Day Breaks (1999).

All these years later, When the Day Breaks continues to loom large over Forbis and Tilby’s careers, and over underground animation as a whole. Made at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), it’s about death, life and animal people. It became a classic.

Which, in the animation world, is a little strange.

That’s because When the Day Breaks is a rotoscoped film — a technique with a wobbly reputation. Many animators write this style off as artless. Yet Tilby and Forbis did something special with it. Here, drawing over live actors gave solidity to the story, and made possible its singularly eye-grabbing look.

The debate around rotoscoping goes back a long way — to the early days of animation. Even in the ‘30s, Disney’s artists were arguing about it when they used live-action video footage to create Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

According to myth, the Disney footage was simply reference — not really for rotoscoping. However, as historian Michael Barrier laid out in his seminal book Hollywood Cartoons, the reality was more complex. Snow White’s animators did trace over video stills. The question was how much tracing ended up in their finished scenes.

In theory, Walt Disney wanted his artists to trace live actors and then create their own, original drawings based on that preparatory work — not just copy. In practice, there was a tug of war between tracing and original art. Certain shots, especially toward the start and end of Snow White, came essentially straight from the footage.

Some at Disney were, at best, skeptical of rotoscoping: instructor Donald Graham called it little more than a lazy cheat. As Barrier wrote, “Rotoscoping was tricky because no tracing of live-action film could do what good animation always did: distinguish the important from the unimportant.”

Grim Natwick, who animated on Snow White, outlined the technique’s pros and cons. Rotoscoping “really did help because you needed a basis to work on,” he felt. And yet:

… you always had to carry it further, and you always had to be very careful that you didn’t depend on the rotoscope.

This battle lies at the heart of all rotoscoping. Is it your tool as an artist? Or are you its tool — a human copy machine? Does it give your animation greater depth? Or does it turn your drawings into weird imitations of their live-action source material?

In Montreal, Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby found their own way through these questions. On the surface, When the Day Breaks has nothing to do with Snow White — but it solved the problems of rotoscoping in ways no less valid or valuable than those of the Disney team.

The whole project began around 1995. At the time, Forbis and Tilby both worked at the state-run NFB. Tilby made paint-on-glass animation — Forbis had just animated on a cutout project called The Reluctant Deckhand. When Tilby decided to do a new film about “the notion that we are more than the sum of our parts,” she brought Forbis on board.

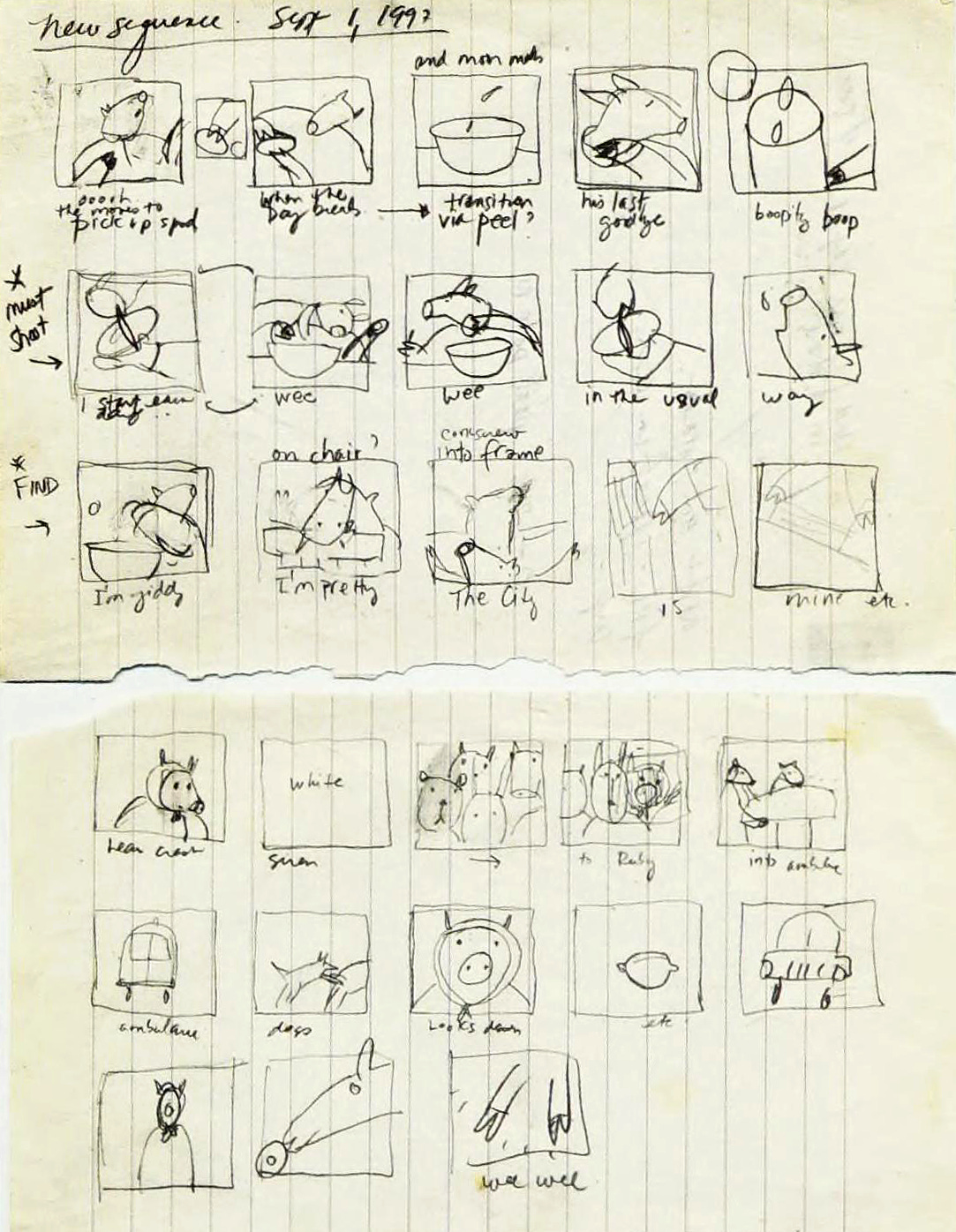

This kicked off the four-year creation of When the Day Breaks.

The pair didn’t set out intending to rotoscope. They “experimented with various styles and techniques” before landing on that one, they explained. Early on, the characters in the film weren’t even animals. The directors tried different types of animation (“cutouts, naïve line drawings, paint-on-paper”) without success.1

Then came the video printer. It’s not a device you’d associate with animation. As Tilby said in a fantastic interview with Skwigly, video printers appear mainly in the medical world, generally for ultrasounds. You can see a picture of one here.

Equipped with rolls of thermal paper (the stuff used to make receipts), the video printer allowed Tilby and Forbis to turn video footage into scrolls of stills. “We were immediately attracted to the photographic images that were neatly contained in film-like strips,” they wrote.

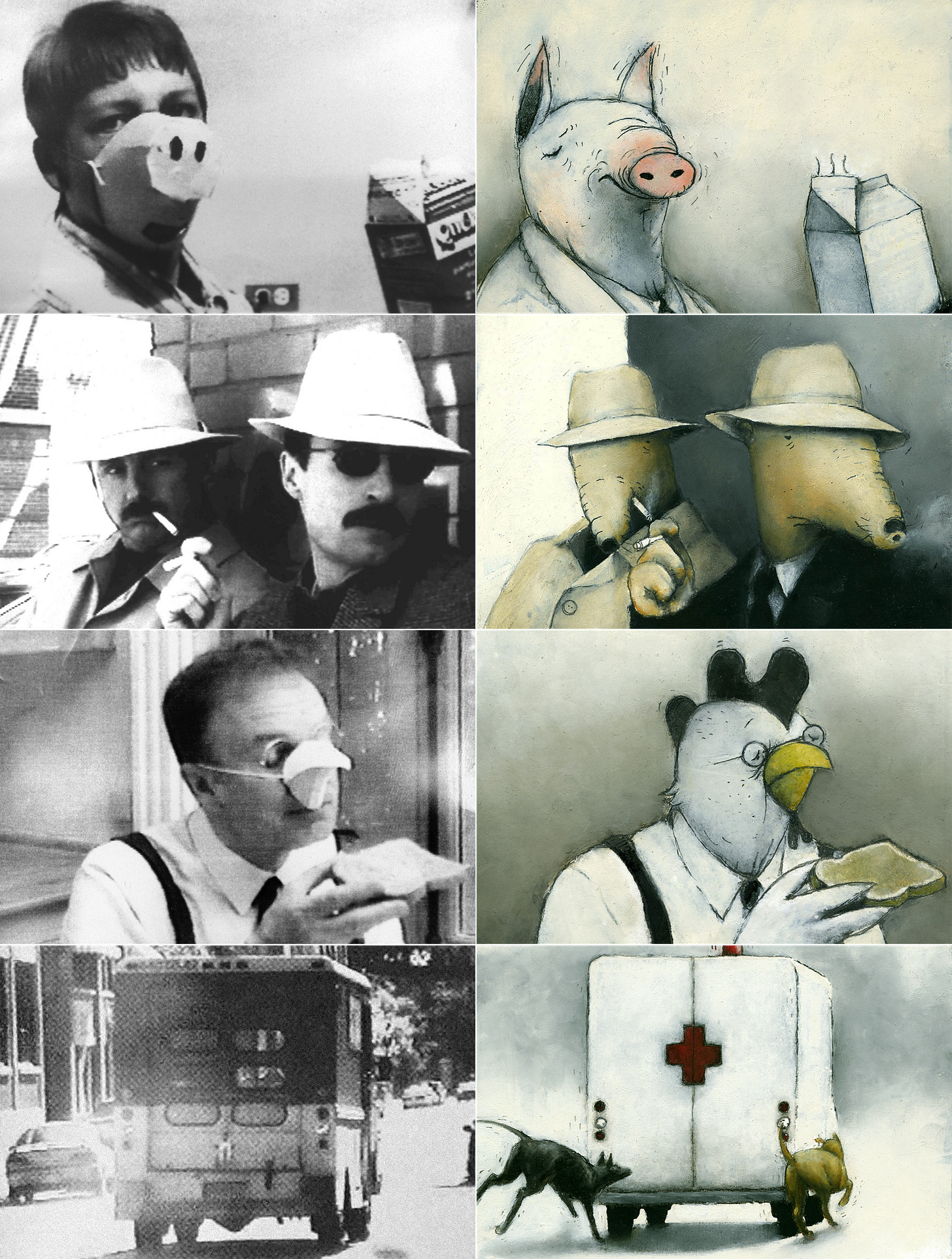

Based on their experiments, a system was born. They would use live-action video to build their shots, and then transform the human actors into animal people — characters who could bring “a lightness and sense of fun” that balanced out the heavier parts of the story.

Here’s how Forbis described the setup in 2000:

First we shot live action on a High 8 video camera (nothing fancy). We used our friends or ourselves as actors to get the basic movement without worrying too much about the aesthetics of the video. Then we went back to the studio and selectively printed out frames of the action using a video printer, which creates small 4x3 thermal black and white prints. We usually manipulated the action, speeding it up, slowing it down or sometimes reversing the order. After that we photocopied the whole shot and painted over the action using oil sticks and pencil, turning humans into animals.

The source video, by their own admission, wasn’t good. “They were terrible looking props; they looked like they’d been made by a six-year-old,” Forbis told Skwigly. The pair just needed something as the raw material for the animation. The important part was what they did with it.2

The secret to the look of When the Day Breaks was creative reinterpretation. It was never just a matter of copying.

That started, like Forbis mentioned, with the editing and retiming of the footage. The pair set about “subtracting, repeating or reordering,” freezing frames, changing the speed and more. Forbis said in the Skwigly interview:

With the subway shot, we actually took the train coming in and then just repeated it going out again, just flipped the shot, so we pulled all kinds of little tricks to make the movement a little more interesting.

It was “a process of selection” that separated the important from the unimportant. In a way, it was similar to what Grim Natwick had done during Snow White. His assistant recalled that he would “throw out every other [frame], or every ten of them, or something, retime it all, analyze it” and so on.

But Forbis and Tilby used their source material to create finished shots in a very different way. After photocopying the thermal printouts they wanted onto bond paper, the live-action stills became canvases. According to The Animation Bible:

Tilby and Forbis used pencil, Shiva Artist’s Paintstik oil colors and rubber-tipped color shapers to draw and paint characters following the images on the paper; in other words, the animals in the film were created on top of live-action references that resulted from the videotaping and printout processes. Extra animated imagery was added to the scenes, while unwanted details were painted over. […]

Because the oil stick color could be applied in a thin layer and was relatively “dry” (in comparison with tube oil paints), bond paper provided a strong enough support for the application of the color. The main challenge was to control the “boiling” (moving texture) by painting as consistently as possible. Tilby and Forbis would smear a dollop of paint onto a plastic palette, then apply it to the image with a paint pusher. If it seemed a little thick, they thinned it with a clear blending stick.

Forbis and Tilby have made it clear that this process was done “without tracing.” Each black-and-white photocopy was turned into a painting. Although this is comparable to tracing, it ensured that crafting a frame was never a mechanical act. There’s even pure frame-by-frame animation mixed in, like the added animal features on the characters’ faces.

You can feel that freedom in the final product. When the Day Breaks is really a painted film — just one with real images underneath. And Forbis and Tilby approached it as painters. Like Tilby put it to Skwigly, work was “free form” and “very loose in a satisfying way.”

For Forbis and Tilby, rotoscoping was simply a tool. They used it for its strengths and avoided its weaknesses. “Claustrophobic” closeups were tighter and easier to render than wide, detailed city shots, so that’s what they did. And, whenever another technique suited a scene better than rotoscoping, they used it. Here’s Tilby:

Sequences such as the “moving postcard” images of the city and chicken ancestors were paintings on photocopies which we moved under the camera somewhat willy-nilly. Images of bones, cells and blood vessels were derived from Gray’s Anatomy, while the pipes and wires were line drawings by collaborator Martin Rose that we squashed or stretched using the photocopier (if you move an image while the light is passing over it you can get interesting results) then inverted digitally to create the blueprint look.

Ultimately, the process for When the Day Breaks was a best-of-both-worlds thing. Forbis and Tilby could work creatively, but they had guidelines. They could and did add cartooniness, but it was grounded. (As they noted, the “photo-realism retained in some of the backgrounds lent substance to the characters and the city and gave the film a gritty documentary tone that we felt suited the story.”)

At every stage, they found themselves choosing what to include and what to omit. They took the raw material and, as Natwick said, carried it further. They extracted the important from the unimportant.

Forbis and Tilby’s methods were unusual. This isn’t the only right way to rotoscope. The style in Snow White isn’t, either. Rotoscoping has many effective uses — like the otherworldliness it brought to 1970s psychedelic animation. Or the awkward oddness it gave to On-Gaku: Our Sound. Or the way it powerfully accents The Snow Queen.

What all of these films share, though, is intention.

Rotoscoping can be a dangerous tool — used the wrong way, it makes for a finished product that feels nonspecific. Something that lacks the subtleties of live-action footage, but also any real artistic intent. But there are other ways to use it. Right ways to use it. And When the Day Breaks gets it very, very right.

This is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on June 17, 2022. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — now, we’ve made it free to all.

2: Animation news worldwide

Drone — and the problem of American indie animation

Late on Sunday, February 5, animator Sean Buckelew debuted his new film Drone on YouTube. It made its world premiere in 2022 at Annecy, the most important animation event in France (or anywhere). It’s an incredible piece.

Drone is a little hard to categorize. It has the clear point of view you get with a great personal film — and yet its technical and storytelling ambitions make it feel like a big production, which it wasn’t at all.

It’s about an AI-controlled military drone called Newton, who adopts anti-war views and goes rogue during a PR stunt by the CIA. As the audience, we see the public reaction and private freakout, as well as Newton’s own travels and monologues on life.

Drone is billed as a satire, but most of it feels all too real. And it pays attention to little parts of the 2020s (the way people talk, the way phones integrate into everyday life, the way viewers post “F” in livestream chats) that animation often leaves out. There’s a lot packed into its 15 minutes — executed with, again, huge ambition.

That stands out particularly because Buckelew lives in America, a country with “essentially zero government funding for this kind of work” — as he wrote today in a detailed behind-the-scenes post about the making of Drone. There wasn’t a place for his film in California’s commercial animation scene, either. To tell the story he wanted to tell, independently, he had to find another way.

This kicked off a globe-trotting adventure. Buckelew and his associates, especially producer Jeanette Jeanenne, first tried to enter the European co-production system by way of Croatia. When that failed, they tried the National Film Board of Canada. At each step of the process, the Drone project improved and they gained connections.

But none of it worked.

In the end, demoralized, Buckelew was able to land two of the hard-to-get grants that exist in the United States. He told us by email that he “applied to a lot more” than the Berkeley Film Fund and Guggenheim Fellowship programs that ultimately allowed him to make Drone. He found the process totally different from Hollywood.

“It was basically the opposite of industry pitch-writing,” he told us about the Guggenheim application, “where you try to simplify everything — it was presenting the most intellectually complex version of the film.”

For anyone trying to navigate their own independent film production, Buckelew’s write-up about Drone is a valuable resource. He goes over just about everything, in depth. It’s fantastic. And so is Drone itself — a film that realistically shouldn’t exist, but somehow does. Find it below:

Newsbits

Substack writer and animation legend

published something special this week. Through AWN, she’s making public a 1979 interview she did with Art Babbitt — in full for the first time.The earliest known work of Chilean animation, La transmisión del mando supremo (1921), was long believed to be lost. Last month, a copy was finally found.

Australian animator Felix Colgrave (Double King) dropped a trippy, mind-scrambling new film called Donks on YouTube. “An exploration of ocean plastic, avatars and adaptive bottom feeders,” reads the description. “The musical!”

The Danish short Mano, a gritty CG piece about two brothers, is free and worth your time.

In China, Boonie Bears: Guardian Code continues to break records in theaters. It’s risen above 1.2 billion yuan ($177 million) since its debut on January 22, becoming only the third Chinese animated film to do so — behind Jiang Ziya and Nezha.

Also in China: Deep Sea hit 629 million yuan (around $93 million) — and the next film by Liu Jian, director of the excellent Have a Nice Day, will compete at the Berlin Film Festival.

In France, the poster for Annecy 2023 was revealed. Created by Jorge Gutierrez (Maya and the Three), it celebrates the festival’s focus on Mexico this year.

As we’ve noted, Russian animation is undergoing a licensing crisis: as foreign software licenses expire, renewing them is often impossible due to the war. Now, Voronezh Animation Studio (Secret Magic Control Agency) is preparing to release its own commercial animation software in 2023, backed by state funds.

Another from France: Iran-born director Sepideh Farsi, known for her live-action films, will premiere her first animated feature at the Berlinale. It’s called The Siren, and it’s been in the works for years. Animation Xpress has details.

Lastly, as we alluded to, we wrote about Hayao Miyazaki’s guide to watercolors in a public issue on Thursday.

Until next time!

From the interviews with Forbis and Tilby on this site and in the book Animation in Context: A Practical Guide to Theory and Making. We reference these many times.

When the Day Breaks began as grimy, 8-millimeter VHS footage. It ended as a series of handmade paintings shot with a 35-millimeter rostrum camera. From VHS tapes to black-and-white printouts to black-and-white photocopies — and somehow to a rich, beautiful end result.

Pretty unique art style! Also love how people were turned into a different animal. Have great respect for artists and animators. Officially subscribed to this Substack.

Wow. I went to Sean Buckelew's substack and read the entire story. Holy smokes. GREAT JOB covering his story. As an independent filmmaker I can feel his pain and joy. I wish we heard more stories like that. You folks ROCK for sharing that. And Sean if your reading this, GREAT JOB.