Welcome! This is a special issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter — we’ve been working on it for a while. Here’s the plan:

1️⃣ Studying the dance from The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon.

2️⃣ International newsbits.

New here? You can sign up for free to receive our Sunday issues right in your inbox — every weekend:

With that, we’re off!

1. Dancing between ancient and modern

The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon is a landmark film. Released in 1963, it was a new peak for Japanese animation. Its influence spread in the decades that followed — reaching Samurai Jack and many more classic projects.

So much about The Little Prince stands out that it’s hard to know where to start. The film announced a new style for Toei Doga, the Tokyo-based production house that gave birth to Japanese animation as we know it.

“The works we were doing until then were realistic, three-dimensional representations for the sake of putting out a ‘real’ feeling,” recalled Yōichi Kotabe, who animated on the film (and later became Nintendo’s signature artist).1 By contrast, the look of The Little Prince is stylized, modern and graphic. It’s like a Japanese take on UPA.

In fact, it’s a blend of the new and the ancient. Despite its mid-century design, The Little Prince is rooted in Japanese mythology. Its artists were taking from older Japanese art, too — especially Haniwa sculptures and traditional painting. The film’s art director, Reiji Koyama, was steeped in the latter.

According to Kotabe, Koyama insisted that the team depict “form rather than mass,” or shape rather than volume. Kotabe described this as a “traditional Japanese understanding” of art. It matches the mythical story — but also the latest trends in foreign cartoons at the time. Flat, abstract forms were in vogue, from UPA to Yugoslavia.

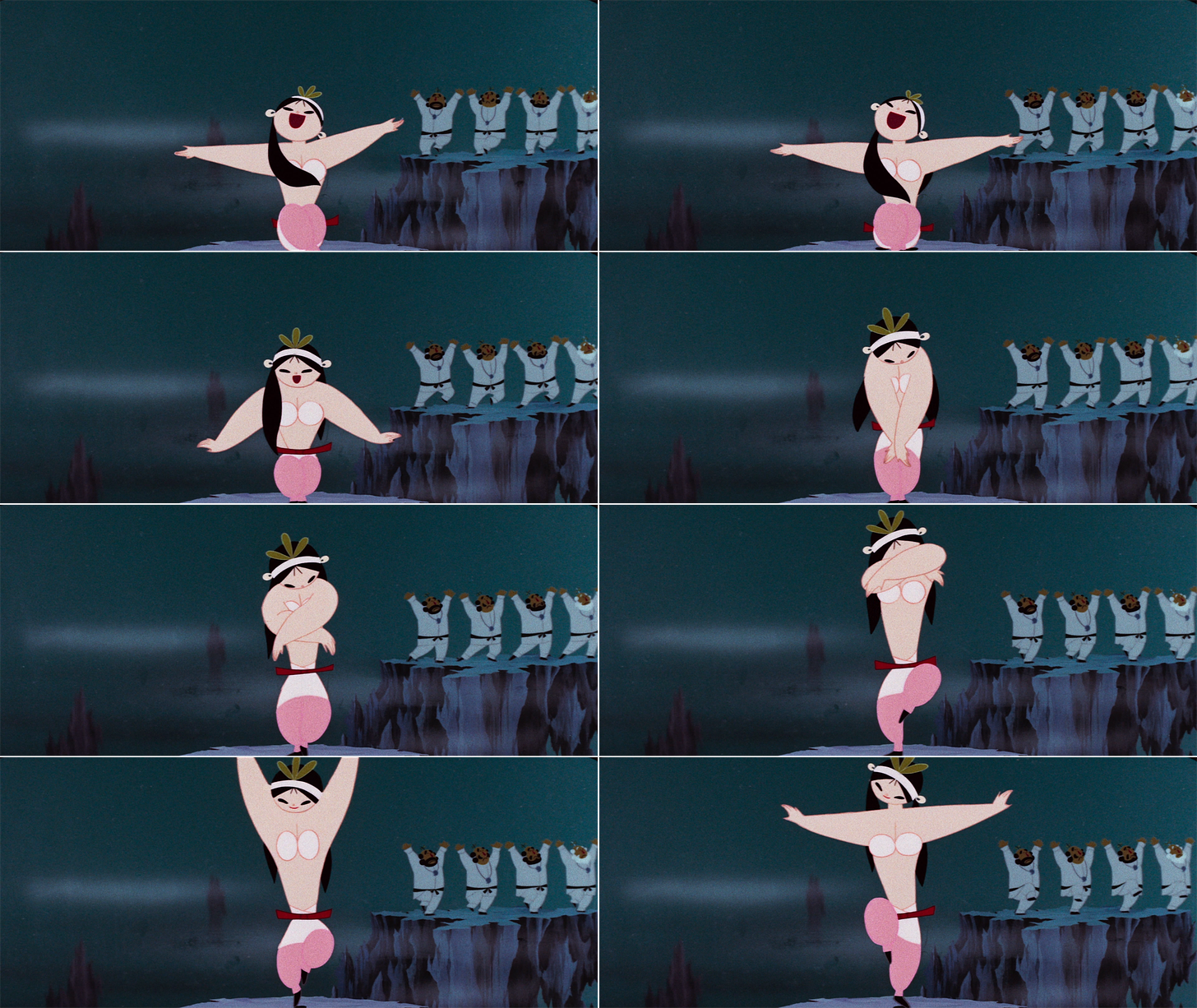

Which brings us to the dance of the goddess Ame-no-Uzume, a sequence halfway through The Little Prince. Arguably no moment in the film more perfectly joins ancient themes with modern animation. It’s not just in the graphic design — the scene embraces a unique, non-realistic style of limited animation. See it below.

(For readers in Japan, the video may be blocked. You’ll find a shorter clip of the sequence on Twitter.)

Uzume’s dance was one of the setpieces in The Little Prince. An incredible amount of thought and effort went into it. Today, we’d like to explore just a little of that.

We start with the sequence’s main mastermind: Makoto Nagasawa, the lead animator assigned to this section of the film. Joining him to animate Uzume’s “backup dancers” was Norio Hikone. Together, they helped to make something special.

Nagasawa, who passed away earlier this year, was one of the innovators at Toei. As an in-betweener on Journey to the West (1960), he was among the first to toy with limited animation — inspired by foreign cartoons like Magoo’s Puddle Jumper (1956), an Oscar-winning film by UPA.

On Journey, Nagasawa experimented. He in-betweened one character with just a few quick smear frames — getting snappy movement that darts between poses. Before long, he developed his own kind of limited animation. Maybe because he’d discovered it as an in-betweener, the theory relied on creatively cutting out in-betweens.

Limited animation has many styles. In Yugoslavia, they often did it “on ones” (24 drawings per second). They used close, even in-betweens — but also loops, long holds and tricks like animating only one part of a character. For UPA’s famous bear ballet scene, Art Babbitt drew full, complete motions mostly “on twos” (12 drawings per second) but timed them to use stops, starts and hard freezes in the final film.

With Uzume’s dance, Nagasawa used a third style. Like Disney, he animated full-body motion on “ones” and “twos,” and he didn’t employ much looping or freezing. But he still rejected naturalism. “In general, I’m not good at realistic movements, and I didn’t want to do them,” he explained. Again, he aimed for snap.

Typical motion at Toei, Nagasawa said, would be “neatly in-betweened from the first [key] pose to the last [key] pose.” In other words, in-betweens smoothed out the movement and made it longer, more complete and more realistic. By contrast, Nagasawa’s drawings of Uzume are often at wide intervals, with minimal in-betweens. Sometimes, she basically teleports from one frame to the next.

Even when the intervals aren’t that wide, the way Uzume moves remains big, broad, clear and non-real. Nagasawa pushes her gestures, increases her speed, shows us only what he wants to show us. The action is crisp, always holding its abstract shape. No naturalistic touches distract from the core form of what Uzume does.

Just as Uzume’s graphic look boils her down to the essentials, so does Nagasawa’s animation. One commentator noted that “Uzume’s movement is full animation [on ones and twos], but it’s limited, or rather the feel of the poses is very sharp and well defined.”

But it’s a mistake to attribute too much of this scene’s strength purely to Nagasawa’s animation. No key animator imagines all this at their drawing desk. The impact we feel while watching the dance built up over time, requiring many people, many stages.

The idea even to do a film based on Japanese myths came to Toei as early as 1958. The Little Prince got underway with the working title The Rainbow Bridge in January 1960. From there, the script took until mid-1962 to complete. Screenwriter Ichirô Ikeda said that he wanted to do something “rich in tremendous, vivid fantasy.”

In the script, the dance occurs from scenes 96 to 98. It opens simply enough: “Ame-no-Uzume jumps out [of the bonfire] and starts dancing.” After a certain point, it tells us that “the depiction of the dance gradually becomes more fantastical.”

“Ame-no-Uzume dances in the sky, scattering beautiful stardust with each swing of the branches in her hands,” the script goes.

Meanwhile, The Little Prince’s visual style, which infuses this sequence, came from staffers like Reiji Koyama and animation director Yasuji Mori — one of the greatest animators and designers of all time, and the mentor to Hayao Miyazaki. According to Nagasawa, Mori felt the need to do something new, inspired by modern, limited animation at the time.

“There is no doubt that Mori-san was at the center of the change in the Toei Doga style,” Nagasawa said. But the roots of the change were ancient, too. They involved deep research — among other things, Mori and the team visited the Ise Grand Shrine.

Here’s what Mori himself said about The Little Prince:

The characters adopt as many archeological, ancient symbols as possible. But, to capture archeological life and emotions … I worked hard to put them out in a human-like manner. The lines were also simplified, and, stylistically, I intended to make them easier to draw.

Koyama explained his goals with the colors and backgrounds like so:

This time, without being bound by reality, I want to try expanding the possibilities of fantasy as much as possible. Since this is a dream world, I want to construct it such that the treatment of space is abstract, and the colors are also artificially beautiful.

The look of Uzume herself came about in a somewhat unorthodox way. For The Little Prince, Yasuji Mori designed the characters and created their model sheets. But many artists on the team drew rough design proposals for the cast, competing to be picked as Mori’s foundation. According to Nagasawa, his own design for Uzume won.

But this was only the beginning of the sweat and blood that went into Uzume’s dance.

For more, we turn to the words of Yūgo Serikawa, the overall director of The Little Prince. Serikawa saw this sequence as an achievement for Toei Doga as a whole. It was highly collaborative. According to him, its realization began like this:

The first thing to do was to gather the members of the team, including Yasuji Mori-san, the animation director; Makoto Nagasawa-san, the key animator in charge; myself, the director; Isao Takahata-san, assistant director; Takashi Iijima-san, producer; Akira Ifukube-san, the composer; and Emi Hatano-san, the choreographer … Many detailed meetings were held around the storyboard (everyone was enthusiastic and quite insistent), and piano sketches were repeated at the Ifukube residence. At one point, Ifukube-sensei said, “Here comes the timpani rhythm. Iijima-san, try hitting the bongos there in time with my piano!” The producer was ordered to help out, and Iijima-san was so enthusiastic that he played the bongos with great aplomb. Once things had been established to a certain extent, a test disc was recorded with a small orchestra … Finally, a full-length recording was made with nearly 50 members just for this one piece of music. It was a masterpiece, the very essence of Ifukube melody.

There were stars in this planning team. Ifukube was the composer for films like Godzilla and Akira Kurosawa’s Quiet Duel. Isao Takahata would go on to be one of Japan’s best directors — Heidi, Grave of the Fireflies and beyond.

Planning the dance, and designing the music and pictures to sync, was a team effort. Nagasawa said that the whole process was new to Toei. The crew batted around ideas, developing the scene through sketches and suggestions. At one point, Nagasawa did a rough pass on the storyboards, refined further by Serikawa and Mori.

Much of the power, energy and excitement of the dance sequence originated in these meetings. Here, the dynamic compositions of the final scene came into being — and many loose, lively drawings paved the way for the completed animation. Below, a few pages of the storyboard:

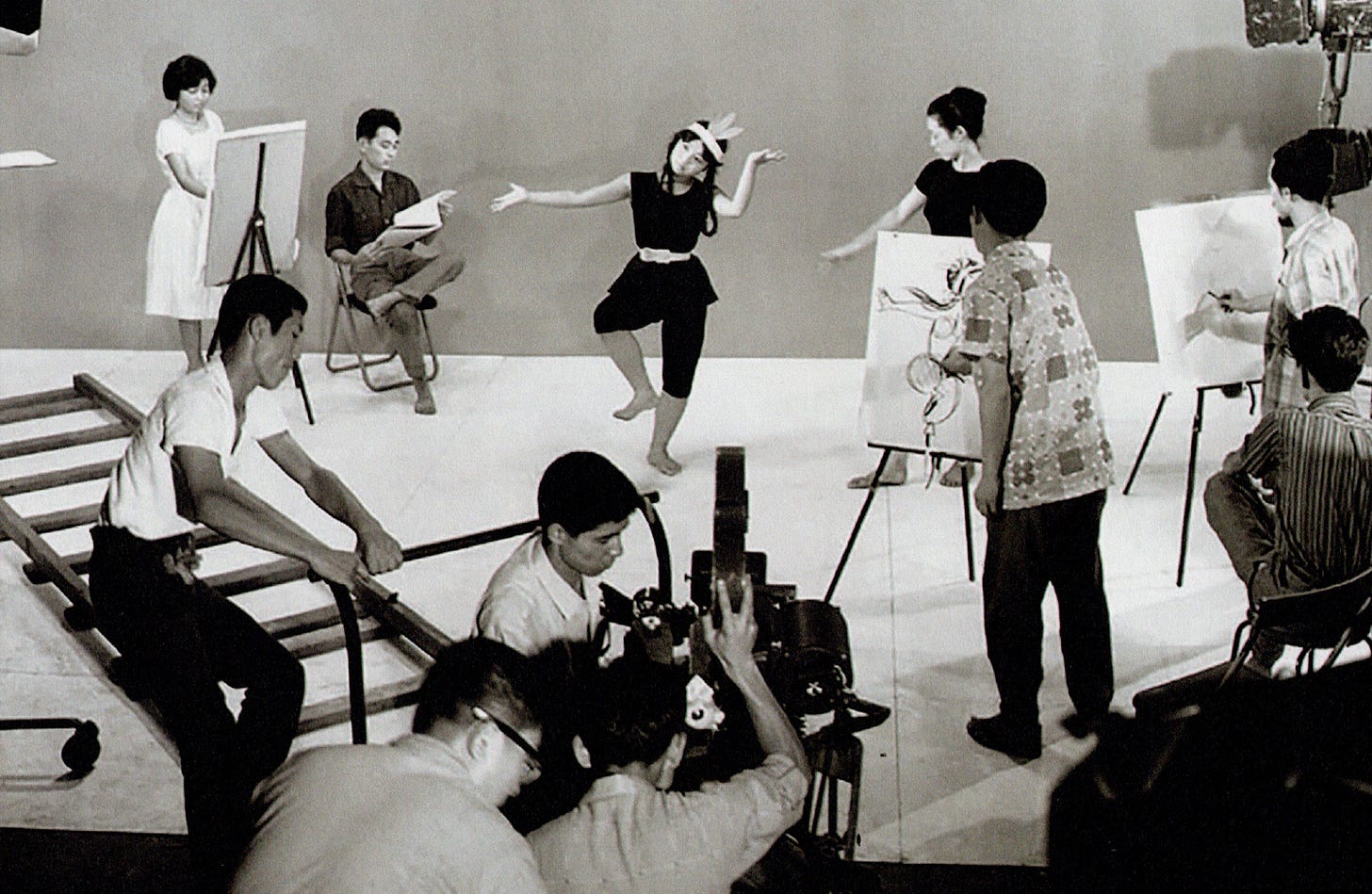

Next, Serikawa wrote, “things got tough.” The meetings developed into full-blown choreography sessions, featuring live dancers. Like Disney, the team filmed reference video as a blueprint, grounding the dance in life. The idea wasn’t just to trace the video, but to use it as a guide for the motion, poses and overall shots.

Serikawa again:

Emi Hatano-san, Nagasawa-san, myself, Takahata-san and Norio Hikone-san, who was in charge of drawing the four-member “Takamagahara Dancing Team,” joined us for a series of choreography meetings. Partway through, four men from the Hatano ballet company (dancing team) and a woman playing the dancing Uzume … joined in, meetings were repeated with actual dancing and more than 40 live-action shots were filmed on a hot summer day. All the shots were the same size and from the same angles as the film’s storyboards (a puppet was used for the part where Uzume flies in the sky).

It was grueling — the team had little experience with this pipeline. Serikawa had to figure out how to direct the dancers to the prerecorded score, which he’d never done before. He noted that Takahata struggled even to work the clapperboard. All in all, a devastating day.

But the attention to detail paid off. It made an ambitious scene — one with radically challenging motion and camerawork — possible. It allowed Toei to do cutting-edge animation that nevertheless stayed attached to reality, and by extension to tradition.

All of which only hints at the full labor that went into Uzume’s dance. It doesn’t get into Nagasawa’s back-and-forth with Reiji Koyama on the animation, to ensure that the backgrounds fit with the characters. It doesn’t mention Serikawa’s animation reviews, or Takahata’s even more rigorous reviews of the in-betweens and final drawings, which he did throughout The Little Prince. Serikawa wrote that Takahata left no stone unturned.

And it doesn’t bring up the nightmare of coloring and finalizing the painted stars, the “beautiful stardust” mentioned in the script, toward the end of the scene. Even Nagasawa helped with it. Nothing about it went easily.

The Little Prince was a huge undertaking — this dance represented only four minutes of it. Reportedly 180 people contributed to the completed film, which absorbed at least 250,000 drawings and one ton of paint (in 170 different colors). The project was sweeping. It was also, in a sense, a statement of intent for Toei.

The team was well aware of the trends in world animation at that time. According to Nagasawa, they were watching work from Canada (Norman McLaren), Czechoslovakia (Jiří Trnka), Russia (The Snow Queen), France (The King and the Mockingbird) and so on. It was all bold, new animation. In The Little Prince, Toei took up the challenge this work presented, without simply copying it. The team contributed to modern animation while staying rooted in the ancient, and in Japan itself.

Uzume’s dance is a microcosm of Toei’s achievement here. It’s a famous moment in Japanese mythology, and its style draws heavily from ancient art. But it’s also fresh and new — putting Toei side-by-side with the most exciting animation of the time.

In just a few months, this film — and this dance — turns 60. With the recent Blu-ray release from 2020, it’s never looked better. As the work of Nagasawa and the rest of the Little Prince team slowly enters the past itself, it’s worth revisiting. To draw a lesson from Uzume’s dance, nothing gets you to the new quite like the old.

Today’s issue had been in the works since May 2022. And it wouldn’t have been possible without the pseudonymous historian Toadette, who translated a huge amount of text for us. It was an irreplaceable help. Check out Toadette’s YouTube channel and animation research blog On the Ones — both are breaking ground.

2. Newsbits

The Irish film Fall of the Ibis King is aiming for the Oscar shortlist. As part of its campaign, it’s available for a limited time via Vidiots. It’s an incredible piece (10 minutes long) that we can’t recommend enough. We wish its team luck.

On that note, the Canadian short The Flying Sailor (another Oscar hopeful) is streaming for free via The New Yorker.

One more Oscar-related story: the Estonian film Sierra, one of the best animated shorts of 2022, has a making-of article on Cartoon Brew.

In Mexico, El País dove behind the scenes of Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio. Among other things, we learn that 3,443 frames of the film were made in Mexico. Production manager Aranza Engle says that Pixar may reign supreme in 3D, but puppets are another matter: “Mexico can compete with stop-motion.”

Also in Mexico, a global call for submissions is open for the 28th “Festival Internacional de Cine para Niños (… y no tan Niños).”

The Japanese filmmaker Takahide Hori (Junk Head) had a filmed conversation with Phil Tippett (Mad God), who said, “We must’ve hatched out of the same egg.”

My Better World, produced in South Africa with help from a pan-African team, won an International Emmy. Big news for a show that’s doing a lot of good.

In Ukraine, a series of animation events called “Мами видихають” (roughly, “Moms Exhale”) will be held next month in the cities of Lutsk, Chernivtsi and Uzhgorod. Meant for displaced mothers and children, and funded by Germany’s government and Goethe Institute, it includes art therapy and film screenings.

The Japanese film Jujutsu Kaisen 0 has now earned over $191 million worldwide, making it one of the top-six anime films of all time by international gross. Meanwhile, Suzume by Makoto Shinkai continues to hold #1 in Japan for its second week, as One Piece Film: Red claims fourth place.

Lastly, we wrote about the so-called “Hungarian school of animation,” from renowned classics like Son of the White Mare to films made out of gingerbread.

See you again soon!

Kotabe’s quotes come from an interview in the booklet for the recent, limited-edition Blu-ray box set of The Little Prince, released in Japan. This box set (the booklet plus other materials) is our main source for the article. We also used Nagasawa’s 2004 interview with Anime Style, and two 1980s write-ups by Serikawa, as reprinted by Anime Style.

The sheer effort of the creators shows in this article, each description building the tension laying out the challenges, the fact that they managed to achieve almost every crazy ambitious goal they set out to with this scene (and you can see this in the boards) is truly a testament to their tenacity. If you aim for the moon, u might end up making stardust

oh my god that dance sequence is absolutely gorgeous, especially the moment where the stars start leaping from her the fx animation eats everything up god I can't put into words how beautiful that scene is