Welcome back! Another week, another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our lineup for today:

One — looking at the beauty of so-called “limited” animation.

Two — animation news from all around the world.

Three — a bizarre retro ad for Levi’s.

Four — the last word.

If you’re new to the newsletter, now is a great time to sign up! It only takes a second. Catch our Sunday issues in your inbox for free, every week:

Now, let’s go!

1. Unlimited animation

When we go to praise the way animation moves, it’s tempting to reach for the word smooth. On Twitter, it’s the compliment we see the most. We often want to call animation good when it feels smooth, and bad when it feels choppy — when it feels limited.

This idea deserves a closer look, though. Take the infamous 3D film Foodfight as an example. It animates “on ones” — that is, it updates with a new frame of animation 24 times per second. That’s the smoothness of a live-action film. By comparison, even Disney’s retro classics were often animated “on twos,” or at 12 frames per second.

So, Foodfight is smoother than most of Pinocchio. But the way it moves is still cold and lifeless. Being smooth doesn’t give it a free pass.

Meanwhile, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse embraces choppy motion, jumping unrealistically between poses. And yet it vibrates with life and warmth. Its VFX supervisor notes that “the animation doesn’t change every single frame; characters will be held up for one frame, two frames, three frames, so that their motion looks jittery.” He calls this stepped animation. An older name for it is limited animation.

Limited animation traces its modern roots back to UPA in the 1940s, and the studio didn’t like that term for it. Artist Jules Engel called the name “very stupid.” As Adam Abraham notes in When Magoo Flew, his definitive history of UPA, the team had tried others:

John Hubley used the term “stylized” animation and Bobe Cannon preferred to call it “simplified,” [but] limited, with its sense of the pejorative, is the name that stuck.

It was about much more than saving money, although that was a bonus. Limited animation was an artistic statement — just like the so-called “UPA style” in design. It allowed UPA to break the bonds of reality.

It opened frame rates to wider variation, and characters could freely teleport, loop, freeze and much more. The book Cartoon Modern notes that the casts of many UPA films “move around in a wholly invented graphic manner that is as stylized as their designs.” Pete Docter calls it movement “based on feelings, rather than anatomy.”

Cannon was the master of this technique. He drew his ideas from real-world sources — just not the usual ones. Once, he was mesmerized by the way a train crossing signal arm “moved upward at a different speed than it moved down,” per Cartoon Modern. That kind of motion may not be smooth, but it does feel alive.

The whole thing had other upsides, too. By embracing non-realistic movement, UPA animators could show exactly what they wanted. Gravity, physics and even the rules of animation didn’t necessarily apply. According to Engel, this level of preciseness is the technique’s real magic. He compared Cannon’s work to stage acting:

There isn’t a gesture on the stage that is not truly necessary. In other words, very seldom do you find a really great stage actor where he would use his hands or his head or any portion of his body, where he would make as much movement as the best animator made for Walt Disney. […] You watch Laurence Olivier on stage, and it’s absolutely magic. The gestures are minimal. And this is what Bobo Cannon was able to do on film.

This version of limited animation, of motion that’s carefully clipped to accentuate action, would win over Japan in the late ‘50s. But the whole idea would subtly change in the process.

UPA was on Makoto Nagasawa’s mind as he animated that thrashing man above. It was during the production of Journey to the West at Toei Doga, and Nagasawa was taking notes from the limited animation of cartoons like Magoo’s Puddle Jumper. Still, something was different.

As Nagasawa explained in an interview, his idea of “limited” animation here was to almost eliminate in-between frames. The character jumps from key pose to key pose. This style was rarer at UPA. More than a few UPA cartoons were animated in full motion that looks fluid on paper — but the frames were timed creatively in the final film, making for a limited look.1 Nagasawa’s take was sharper, more abrupt.

He would push through other exciting spins on limited animation, too. One example is his work on The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon. Another is Toei’s rare Motoro the Mole (watch), a clean break from the realism seen in the rest of Journey and Toei’s early work. Nagasawa’s animation is expressive and abstract, with limited frames. But there’s an odd smoothness to Motoro that defies those limits.

Maybe it isn’t that odd, though.

“How smooth the animation looks has nothing to do with how many frames there are,” an animator from Toei’s early days has argued. “2,000 frames would be enough to make the pictures move to an acceptable degree.”

The theory that “smoothness” isn’t strictly connected to more frames had already been proven in Yugoslavia, a few years before Nagasawa’s experiments. UPA’s work had reached a group of young animators there, spearheaded by artist Dušan Vukotić, and it inspired them to invent what they called “reduced animation.”

They started with ads. “Some films took an unbelievable eight cels to make, without losing any of the expressive movement,” scholar Ronald Holloway wrote in his book Z is for Zagreb. In the past, Vukotić and company had made short films with around 12,000 or 15,000 drawn frames. After their stint in ads, they went back to the shorts — lowering the number to between 4,000 and 5,000.

Just as with UPA, limitation actually set Zagreb’s animators free. “By limiting the drawings the characters were freed from realistic movement and given a characteristic life of their own,” Holloway wrote, “thereby increasing the film’s tempo and enriching scenes with new forms of expression.”

Today, it’s easy to read that kind of language as a little exaggerated. This style of cartoon animation has been standard since the ‘50s, after all. But Holloway has a point.

While limited animation may feel commonplace as an idea, it still has the power to surprise us. Spider-Verse and The Lego Movie prove that. Remasters of UPA oldies like Gay Purr-ee prove that. Even after decades of use as a cost-cutting measure, the reality is still that limited animation can be anything — it’s the animation of imagination.

Or, in the more dogmatic words of the Zagreb animators:

To animate: to give life and soul to a design, not through the copying but through the transformation of reality.

2. News around the world

A Korean animated feature approaches

Korea is the land of outsource animation — or so the story goes. While it does have domestic cartoons, Korea’s animated films have a history of flopping at home. Disrupting that narrative was Leafie, A Hen into the Wild, a 2011 box-office smash based on a fairy tale. It holds the record as Korea’s most successful homegrown animated feature.

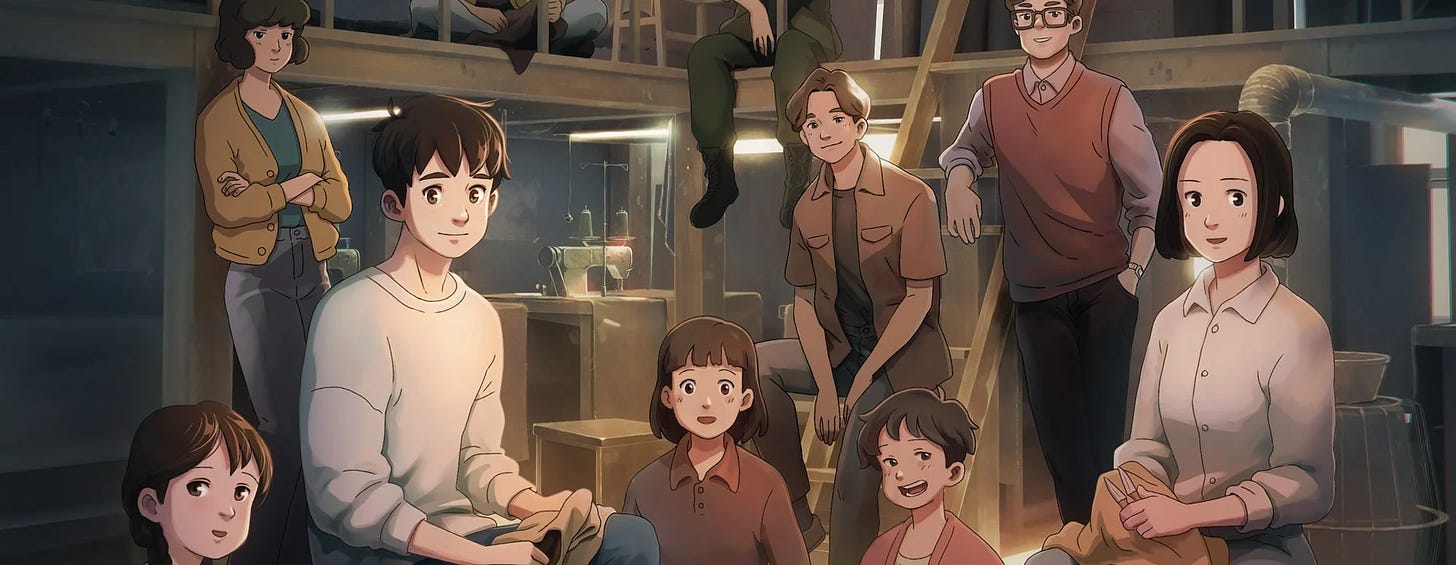

That project’s producer, Myung Films, is now back with its first feature-length animation since Leafie. It’s called Tae-il. This week, we learned that it’s set to premiere in October, at the Busan International Film Festival.

Tae-il is based on the harrowing true story of Jeon Tae-il. He self-immolated in 1970 to protest the poor treatment of factory workers in Korea. Only 22 at the time, he became a martyr for workers’ rights in his country. Tae-il is voiced in Myung’s adaptation by the popular actor Jang Dong-yoon, something of a folk hero himself.

It’s worth mentioning that this film looks great, based on the trailer. The project was crowdfunded through the “Together-Value with Kakao” service — with significant success, per The Chosun Ilbo. We’ll be looking forward to seeing more from it.

Laika returns with Wildwood

Over two years since the release of Missing Link, a critical hit and commercial dud, Laika is back with another stop-motion feature. On Wednesday, Deadline reported that it will be called Wildwood.

The story adapts a children’s novel by Colin Meloy, frontman of The Decemberists. So far, we know that it follows a girl named Prue McKeel who’s searching an enchanted forest for her kidnapped brother. It’s set in Oregon — the hometown of both Laika and the band. Although the studio optioned the rights to Meloy’s book way back in 2011, the film is only now coming to fruition.

Wildwood is being directed by Laika head Travis Knight, known for Kubo and the Two Strings. (He shared the director’s chair on Kubo with Shannon Tindle, whose credit in that role was scrubbed from the final film.) No word on a release date, but we’ll keep an eye on the project going forward.

Best of the rest

Cartoon Brew reported this week that Anne Jolliffe, Australia’s “first woman animator,” died in August at the age of 87. Her pioneering story is one to read.

Meanwhile, the Russian animator Yuri Norstein turned 80 this week. In honor of the event, the government-owned paper Rossiyskaya Gazeta talked to many of his associates and family about their memories of him.

In Indonesia, the government is pumping money into the film industry, including animation. It’s a bid to offset the damage done by COVID-19.

On Friday, director Jorge Gutierrez revealed in a tweet that he’s working on a new feature film with Netflix. “Hint: it has Mexicans and Mexico and Mexican things in it,” he wrote.

We reported in May that the Hungarian animator Marcell Jankovics had passed away at the age of 79. Today, his final work premiered on TV. It’s a 12-part series called Toldi, and it looks undeniably Jankovics-ian.

The Korean drama Yumi’s Cells had a strong debut this week. Based on a major Webtoon, it’s a live-action show that uses charming 3D animation to portray the lives of an office worker’s cells.

Toei Animation’s stock price hit a record high in Japan on Wednesday, in a sign that its business model suits the current climate of the anime industry. (Toei is a rarity — an anime production house and a sales and licensing goliath.)

In Hangzhou, the China International Cartoon & Animation Festival starts on September 27. Wuhu Animator Space has a big preview of what’s on offer.

Then, in South Africa, the Cape Town International Animation Festival is kicking off on October 1.

Lastly, ever wonder what animation people actually watch on YouTube? Cartoon Brew has done the hard work and compiled a fascinating chart.

3. Retro ad of the week

The ‘70s were a time of unorthodox TV commercials. There was a desire, among the top teams, to one-up what audiences had come to expect. The decade kicked off with Magadini’s Meatballs (1970), the groundbreaking ad-within-an-ad you’ve definitely seen before. But things only got weirder from there.

The Stranger is one of those weirder things. From ‘71, it’s an animated spot for Levi’s jeans. A stranger comes into town wearing bright, Dacron polyester pants — which he grants to others with his “beautiful Levi’s magic.” The music is a haunting drone. The imagery shifts between psychedelia and sights from a nightmare. Matched with the gravelly voice of the narrator, it’s as scary as it is funny.

Snazelle Films in San Francisco put the spot together. According to art director Chris Blum, the idea came from “the worst advertising agency in SF” — Honig, Cooper & Harrington, where he worked. Still, they’d struck gold with Levi’s. They did a whole series. The Stranger happened as the ads grew “more extreme” to push test audiences, per Blum:

The Levi’s commercial test scores were going through the roof — higher scores than anyone had ever seen! Then the testing became much more sophisticated — things like pupil dilation, measure of perspiration, body temperature, and heart rate were able to be measured while people were watching commercials in test environments and we still were breaking test score records.

One key was Snazelle’s creative use of rotoscoping. In The Stranger, it gives the motion a ghostly lack of weight and a dreamlike complexity. It’s intense — and it was rare to see at the time. Animator Sally Cruikshank has said that Snazelle essentially “revived rotoscope” with its Levi’s campaign. A trend ensued.

Then there was Ken Nordine, the eccentric “word jazz” artist who narrated The Stranger. Its script and audio adapted his record Flibberty Jib, a dark piece of spoken word. Blum and copywriter Mike Koelker turned it into a story about jeans.

The Stranger was a hit at award shows — and with viewers. Nordine said that it “made a lot of money for the agency, and I made some money, too.” In 1979, after Nordine had appeared in a number of Levi’s spots, Billboard reported that he’d become more famous for selling jeans than for poetry. Or, as he once joked about it all:

What is that saying: ‘You have to serve God and mammon at the same time’?

Find The Stranger below.

4. Last word

That’s all we’ve got for this issue! Thanks for reading. Next Sunday, we’ll be back with more animation highlights from around the world.

We’ve also started doing Thursday bonus issues. While our Sunday issues take a broad look at animation, each Thursday edition dives deep into one specific topic that excites us. We’ve done three so far, unlocked for all readers:

A chat with our favorite animators in India, Vaibhav Studios.

A wide-ranging interview with Jonni Phillips about the 90-minute feature film she’s animating (mostly) solo.

A peek into China’s hit student animation Kaleidoscope, including behind-the-scenes art and its creator’s first interview in English.

Now, Thursday issues are entering their next phase. Future Thursday material will be exclusive to members. We’ve got a growing member community that we’re incredibly excited to share more animation with. Thank you for your faith in us!

Membership costs $10 per month or $100 per year. There’s an additional 40% discount available for students who email us for a special code.

Alongside that, we’ve revamped our Founding Member tier. It now lets you gift a year of free membership to a friend of your choice (just contact us with their email address).

Our first members-only bonus issue, coming this Thursday, will dive into the storyboard wizardry of Katsuhiro Otomo. We’re looking at his storyboards for Akira and his lesser-known classics, like the beautiful Combustible. We hope you’ll consider checking it out.

Hope to see you again soon!

An example of this is an Art Babbitt sequence in Grizzly Golfer. When you play back Babbitt’s individual frames at a consistent rate, one after another, you see a complete and “smooth” motion. It looks different, and full of stops and starts, in the film itself.

Hi, sorry for the late reply. I enjoyed the subject, but your wording made it sound like "full" animation is inherently restrictive. I can think of many examples where that isn't the case but really I don't see why drawing on 1s or 2s is lowkey seen as a bad thing.

Enjoyed this issue as usual, thank you. Still chewing on "Unlimited Animation," a lot there.

A quick comment on news of a Korean animated feature—I'm not sure if I've ever seen one before. I'm Korean-American and was so excited to see your mention of Tae-Il. Of course, not surprised it seems quite intense, dark even. I'm now inspired to dig further into animation from Korea, and festivals there like the one in Busan.

And on the retro-ad: I think I've said something along these lines before—but have commercial advertising just gotten exponentially more conventional in past decades? That Levi's ad! I can't imagine a big company like Nike or Lay's doing something like this now—granted, I suppose the audience for Levi's might be more open to something more abstract or "weird' that doesn't rely on comedy. Honestly I can't see Levi's doing something like this today, either.