Welcome back! We’re here with a new Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and it goes like this:

1️⃣ How Hellboy Animated captured Mike Mignola’s method.

2️⃣ Animation newsbits, and an upcoming film from China.

Just learning about our newsletter? You can sign up for free to get it in your inbox every Sunday:

Now, we’re off!

1: Filming the Hellboy way

How do you turn comics into animation? It’s an age-old problem. Animators were struggling against it even before the first Spider-Man cartoons aired in the ‘60s. And the more distinctive the comic, the harder it becomes to adapt. Animating a Maus or a Billy Bat in a satisfying way would be close to impossible.

Then there’s Hellboy by Mike Mignola. Its style, a dark spin on Jack Kirby mixed with German expressionist film, has been widely imitated since the series started in the mid-1990s. But it’s one thing to steal the look — it’s another to crack the logic of a Hellboy page.

That was the challenge facing the makers of Hellboy Animated — the collective name for two films that remain, to this day, the only major animated Hellboy projects. They debuted on TV in 2006 and 2007, keeping up a cult following since. Hellboy’s creator was involved in these films, but they don’t really look like his comics.

“Mike Mignola wanted the look of the animation completely different than his own and the contract required it,” said Tad Stones, the mastermind behind Hellboy Animated. In Mignola’s opinion, no one had ever successfully copied his way of drawing: it always became a caricature. He wanted to try something else.

So, as Stones and his team sought to stay true to Hellboy, they couldn’t go the obvious route. With Mignola’s visual style off limits, they had to look deeper — into the way that Mignola constructed scenes.

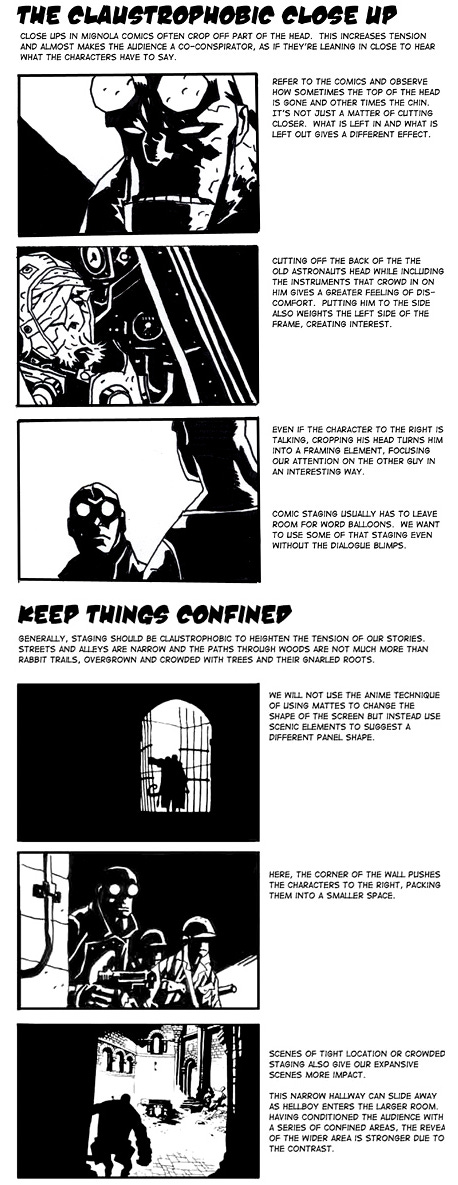

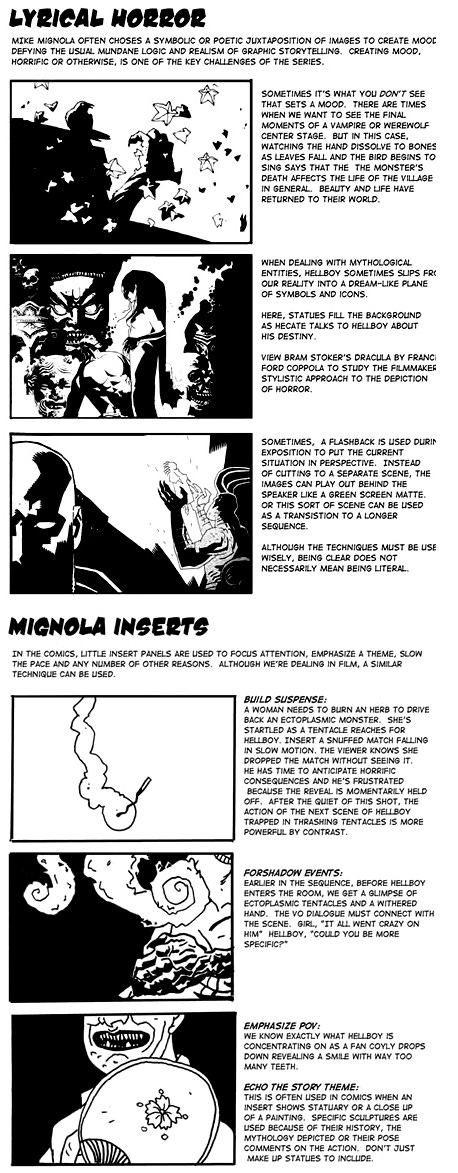

“That means his insert panels, his staging, compositions, whatever we can pull out of the comics,” Stones wrote at the time. To craft authentic Hellboy animation without the Hellboy style, Stones put together a guide for the films’ storyboarders. It broke down the secret logic of Mignola’s method:

Stones was uniquely suited for this job. A longtime fan of Hellboy, he’d tried to get the comic greenlit as a Disney animated series in the mid-1990s. Plus, he was familiar with how Mignola thought. They’d worked together at Disney — during Atlantis.

Atlantis was Disney’s own attempt to emulate Hellboy. Years later, Mignola recalled the moment when the studio told him it was “planning to do a film in [his] style.” He joined the team and found its artists hard at work figuring out how he drew — just as Stones would later do. Some of what they picked up, Mignola wasn’t aware of himself:

… there were these insanely beautiful drawings from Tarzan and smack in the middle of it there was artwork of mine. […] They had enlarged a bunch of comic book pages of mine and put diagrams over them, explaining in terms I didn’t understand, what I do.

Stones and Mignola met on an Atlantis spin-off series. Although it failed, and they both eventually left Disney, that wasn’t the end. On his own time, Stones wrote two Hellboy screenplays. “I pitched Mike some premises and he generously gave me notes on two, half-hour, Hellboy scripts,” Stones remembered. Ultimately, Hellboy Animated came to be.

The films were made extremely quickly — too quickly for Stones’ taste. He wanted to get as close as possible to Mignola’s sensibilities. “Now if we had the schedule of a Disney feature, I know that we could control every frame,” Stones wrote. They could only do their best with the time they’d been given, using Stones’ guide and Mignola’s own input.

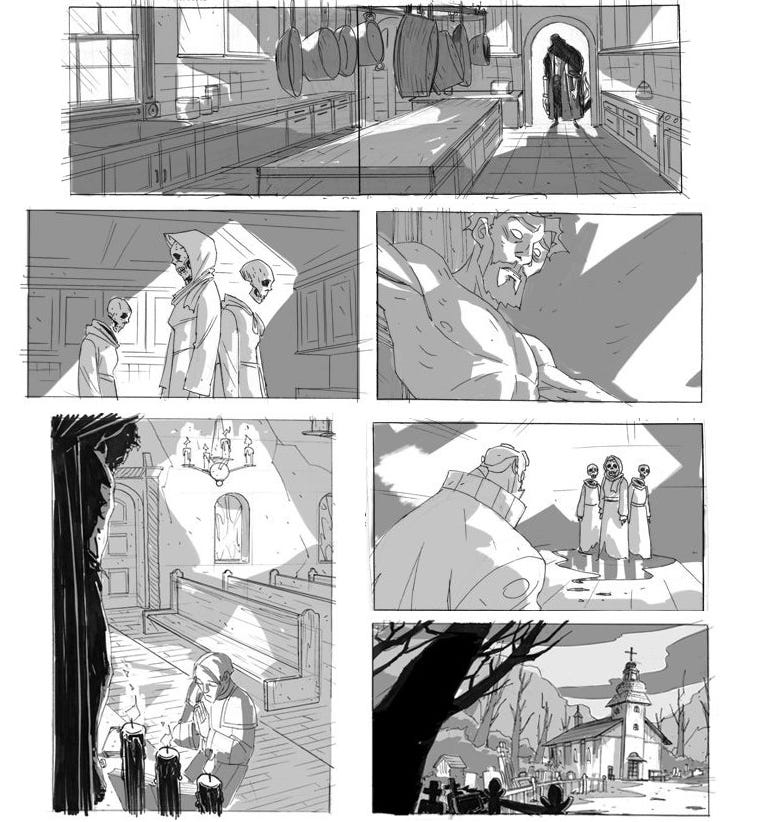

But the storyboard team did impressive work. Even though Hellboy Animated doesn’t look like Hellboy, it often feels like it. This is particularly the case for the second film, Blood and Iron. These assorted storyboard panels for the film, drawn by artist Tom Nelson, clearly show the influence of Mignola’s own type of cinematography:

For one thing, the claustrophobia that Stones identified in his guide is here. See how the foreground tree shoves the church against the side of the screen. How Hellboy’s body frames the ghosts in the distance. How the candles cover the priest. The haunting “insert panel” of the crucifix, with its arms and the top of its head cropped, feels almost suffocatingly close.

Stones’ request that the storyboarders “use scenic elements to suggest a different panel shape” is right there in the kitchen shot. Nelson framed Hellboy starkly against the door — an effect that becomes even more intense and clear in the finished scene.

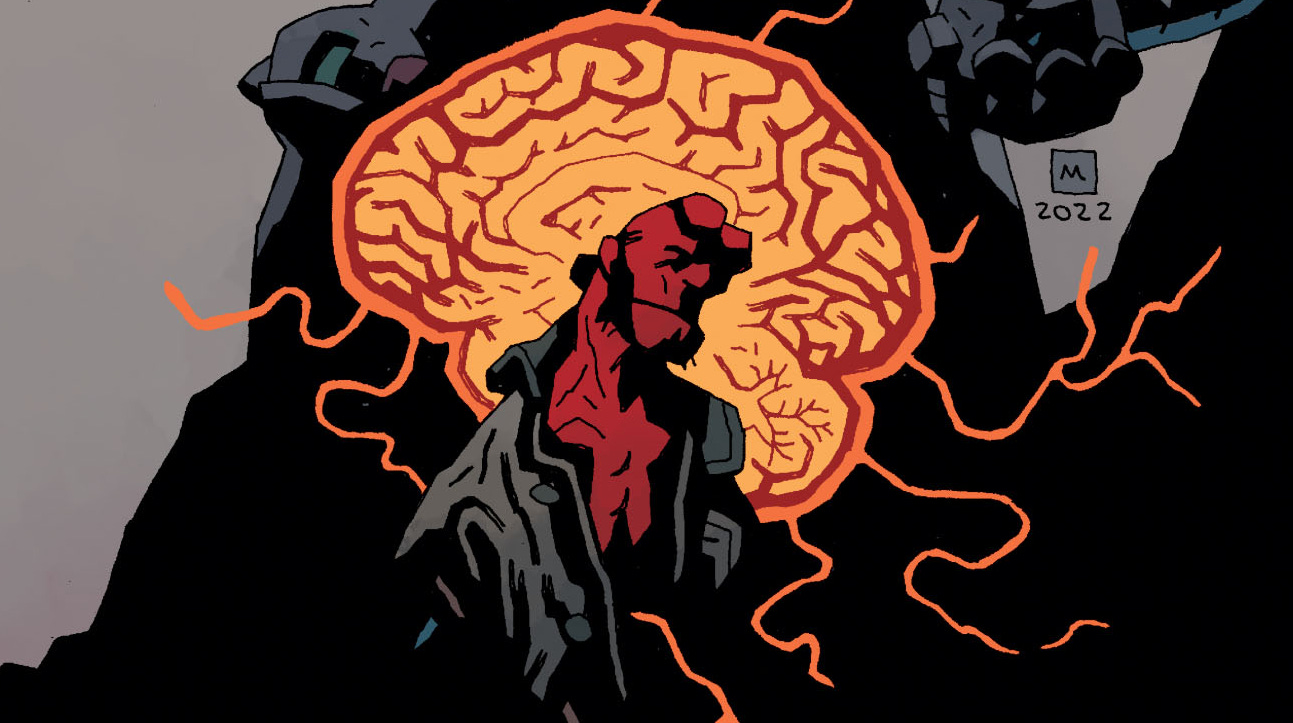

In fact, a lot of these effects intensify in the final art. All of the above panels carried over into the film — with strong results. The shot of the priest is even more claustrophobic and uneasy than in the storyboards:

Like many American cartoons in the 2000s, Hellboy Animated had its actual animation outsourced to Japan and Korea. Madhouse and DR Movie collaborated on Blood and Iron. The American team’s job was mostly to design, plan and polish the film — storyboards, model sheets, color keys, editing and so on.

During production, Stones wrote that the overseas team was “really coming through for Hellboy.” As you can see from the shots above, while there was some drift from the storyboards, things only got more Mignola. In the shot where Hellboy looks at the ghosts, he fills up almost his whole side of the screen — truly becoming one of those “framing elements” that Stones wrote about in his guide.

The result is a case study in how much the fundamentals of filmmaking contribute, quietly, to the feel of animation. It’s even clearer when you compare Hellboy Animated to The Amazing Screw-On Head, a pilot based on another Mignola comic. DR Movie animated it before producing Hellboy Animated. That pilot actually uses Mignola’s visual style. It looks close enough — but something’s missing.

That missing piece is what appears in Blood and Iron. The same studio animated both projects, but the feel of the filmmaking is different. A lot of it comes down to the subtle stuff — sometimes extremely subtle. “Comic staging usually has to leave room for word balloons,” as Stones’ guide says. “We want to use some of that staging even without the dialogue blimps.”

When adapting a comic, even elements this minor make a difference. Nailing a look is one thing. Getting to the heart of what a comic is, as a piece of sequential art, is another thing altogether.

An earlier version of this article appeared in our newsletter on November 21, 2021.

2: Global animation news

The Storm approaches

More than six years have passed since The Guardian (Dahufa), that brilliant and violent cult film, debuted in China. In the gap between then and now, fans and critics have waited for The Storm, the next feature by the same director.

The Storm was due in 2022 but missed the deadline. Then it moved back to 2023, which it’s also set to miss. Yet the delays seem, finally, to be over. The film’s official poster dropped this week alongside a new trailer — and a firm release date. It’s coming to China on January 12, 2024.

If you haven’t seen anything about The Storm before, it’s a 2D fantasy film whose style may bring to mind Spirited Away.1 It looks impressive. Catsuka shared the English teaser trailer earlier this year, and a plot summary that reads in part:

When poverty-stricken Daguzi encounters a child — Mantou — floating downstream at the riverbank, he decides to take him by his side as his son, with compassion and affection. […] Daguzi takes Mantou to the Great Dragon Bay, hoping to find the treasures from the mysterious black ship and to change their desperate situation. However, he is bitten by the monster on the black ship and starts to transform into a monster slowly. Anxious Mantou has to run around and try his best to save his monster father. Meanwhile, because of the arrival of the black ship, all sorts of people begin to gather in the Great Dragon Bay.

The Storm is more family-friendly than The Guardian, but Chinese media outlets still call it “dark,” “sharp” and “weird.” It’s reportedly steeped in social commentary. And it draws, once again, on traditional Chinese visual art. These are the stylistic calling cards of its director, Busifan.

“Busifan” is a pseudonym — his real name is Yang Zhigang. He’s a Chinese animation veteran who originated in the Flash scene online, gaining notice for his 2004 series The Black Bird (watch). After that, Busifan oversaw Mee’s Forest (watch) and Mr. Miao: The Tale of Xiao Ren and the Fire-River (watch). We translated the latter two series this year.

In 2017, Busifan crossed into the mainstream thanks to The Guardian and the Annecy award-winning Valley of White Birds (watch). Suddenly, he was among China’s most-discussed animation directors. That wasn’t a small deal: the animation community in China tends to be harsh toward domestic work — its acceptance of Busifan is unusual. It remains to be seen if The Storm can live up to fans’ high expectations.

Find its trailer embedded below, via Catsuka:

Newsbits

Check out the new trailer for The Imaginary, a Japanese feature by Studio Ponoc. Director Yoshiyuki Momose is ex-Ghibli, but he’s adopted a style here that resembles Klaus in its lighting, volume and shading.

A festival film we praised this year is now public: Swallow Flying to the South. It’s about children during the Cultural Revolution. Director Mochi Lin, based in Canada, wrote on Instagram that her film has been “banned from screening [in China] by cultural authorities due to ‘the sensitive nature of its content.’ ”

In South Korea, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron has dominated the box office for 11 straight days, taking in the equivalent of more than $11 million.

Animation workers at WildBrain (Canada) and production workers at Walt Disney Animation Studios (America) have successfully unionized.

In Russia, Anton Dyakov (BoxBallet) pitched his new feature project Savely the Cat to the state-run Cinema Fund. His feature Ekspeditor was rejected late last year.

Deaf Crocodile has opened Blu-ray preorders for its 4K restoration of Benny’s Bathtub, a Danish film from 1971. See the trailer.

We’ve reported on it before, but the project continues: classic Ukrainian animation from the Soviet era is being restored (officially) on YouTube. Check out this hypnotic paper animation uploaded earlier in the year.

The Japanese Pluto series, based on Naoki Urasawa’s manga, dropped in late October. Producer Masao Maruyama said this about his attitude toward the project: “I have no choice but to do it, even if I die in the process.”

In China, an event by Youku screened the hit Chang’an to over 200 blind students in Hunan. It was narrated live by Wang Weili, a veteran in this field. He said that Chang’an, at almost three hours, is the longest film he’s ever done.

The series Quentin Blake’s Box of Treasures hits the United Kingdom later this year, and it looks charming.

Taiwan’s government is investing hundreds of millions of TWD into local kids’ programming (including animation) to compete with Chinese services like Douyin. Critics argue that it isn’t enough: Taiwanese stations essentially don’t buy domestic animation — they focus on imported Japanese anime instead.

In Japan, an obscure anime feature called Bonobono (1993) is getting an HD premiere on YouTube this month, followed by a launch on digital stores.

Lastly, we published a long interview with Katsuhiro Otomo for the first time in English, with the translation help of the historian Toadette. It’s from the mid-1990s and covers Memories, the rise of computers in animation and more.

See you again soon!

So much to think about and see here! Thankyou.

valley of white birds was busifan??? how did i miss that!! i just came across it on wolf smoke's youtube channel but that explains so much haha, no wonder it was so good. cannot wait for his new film to be translated @.@

the hellboy stuff is really juicy, great advice on shot framing that i fully intend to steal. thank you again for writing, you always bring something fascinating!