Welcome! Glad you could join us for another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter.

These are challenging times, as we wrote a few days ago. It’s impossible to say what 2025 holds in store. But valuable art — the stuff that’s human and true — still matters. Our goal is to share that art, and the stories behind it, to energize and help people in some way. That’s what we’ve always tried to do, and we’re going to keep doing it.

With that out of the way, here’s our lineup for today:

1) Michael Sporn’s Champagne (1996).

2) Animation newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – A local story

Michael Sporn and his films sit just outside the American canon of animation. He was one of the finest animators of his era — a respected, Emmy-winning and widely-seen artist. But he didn’t do big TV shows or Hollywood features.

Instead, Sporn worked for Sesame Street, directed straight-to-video shorts for Random House, made animated specials for early HBO. He adapted Abel’s Island, Doctor De Soto, The Marzipan Pig. To these projects, he brought his boundless creativity.

“The films that we’ve done at the studio have all been commercial films,” he once said, “but they have to have an artistic bent to them or there’s no reason for me to have done them.”1

Sporn spent the ‘80s, ‘90s and ‘00s as a quiet force in East Coast animation, making beautiful work in spaces that most viewed as ephemeral. Writing for Criterion in recent years, Dan Schindel noted that these films exist in the:

… realm of children’s entertainment that survives mostly on the margins of collective consciousness. The average person is unlikely to know Michael Sporn’s name, but if they are of a certain age, they almost certainly have seen at least one of his animated short films, and there’s even a chance they still hold such a film close to their heart. Of the more than forty shorts Sporn directed in his four decades as an animator, little more than a dozen are currently available on legal streaming services in the U.S.

Sporn’s film Champagne (1996) has landed in this situation, too. It’s a small gem: 14 minutes long, smart, lovely and inconspicuous. And it’s a true story — an animated documentary.

In it, we hear from Champagne Saltes, a 14-year-old girl from New York City. She’s being raised by nuns — her mother is in prison for killing someone.2 Champagne doesn’t sugarcoat the story of her life, which is harrowing, but she’s upbeat and optimistic about her future. She looks for the good in things.

It’s an inspiring, unsentimental piece. In 1999, the Chicago Tribune called it “the toast of the animation festival circuit.” Champagne became a success in the education sector as well, according to Sporn. But it’s fallen out of the conversation today, despite how great it still is.

Sporn’s studio was located in Manhattan, at 632 Broadway, when the idea for Champagne came through the door. Champagne Saltes brought it in herself.

She was living at the time in My Mother’s House, a children’s shelter in Queens, run by nuns. There was a simple reason for the name: it gave kids “an unembarrassing answer” to the question of where they lived.3

One of Sporn’s close associates, screenwriter Maxine Fisher, read to the children at My Mother’s House in her spare time. She also screened films by Michael Sporn Animation — having written many of them herself. As Fisher remembered:

At some point, months after I had been reading to Champagne on a regular basis, I got the idea of taking her out to Manhattan. And we began to tour museums, and saw films together, and one day I brought her to [the] Michael Sporn Animation studio. Because she was curious about it; she wanted to know where the films were made which I had been bringing the kids.

Champagne showed up one Saturday and, exploring the studio, had a thought: “she asked if I could make her a cartoon character,” Sporn recalled. It was a spur-of-the-moment thing, but he went for it. “I pulled out a DAT recorder and a microphone,” he wrote, “and I interviewed her for about two hours.”

Sporn and Fisher asked Champagne about her life with the nuns, about her early childhood, about visiting her mother in prison. She gave them revealing answers. Champagne proved to be a lively, funny, engaged interviewee — despite the darkness of her story. She’d been neglected and malnourished as a young child, during her mother’s years as an addict. She’d bounced to her grandmother’s house, and finally to the nuns.

But the nuns were a lifeline. With their help, Champagne was getting on her feet — going to school, learning how to live. She expressed all of that in her answers.

Champagne’s turnaround at My Mother’s House appealed to Sporn as a film concept.4 He suspected that at least one of his contacts would like it, too. Sporn worked with everybody back then — publishing imprints, film distributors, TV channels and beyond. Yet he had no luck this time. As AWN reported:

When Sporn brought the idea to a backer with whom he had worked successfully before, he was surprised to hear that they were not interested, in fact, could not imagine anyone being interested in such a story.

And so Sporn decided to take a risk. Champagne became one of his rare self-funded films, made on the side as his studio did paid client work. It took them three years.

Sporn projects were always low-budget, but the money for Champagne was short enough that he had to animate the film essentially by himself. “I was pretty much all that I could afford,” he later wrote.5

Before the drawing could begin, though, the team needed to edit Champagne’s interview into a narrative.

Improvised dialogue was a staple of John and Faith Hubley’s films — see Windy Day, for example. Sporn came up under the Hubleys in the ‘70s, but, at his own studio, he rarely used improv recordings. Most of his films were scripted. In fact, each one had to be carefully planned and managed to get made at all: “because the budgets are tight, we have to very closely, closely control every aspect,” Sporn said in 1993.

Adding improvisation to that process, or deviating from the storyboard, was a balancing act. Sporn wanted this sort of freedom in his films, but it was dangerous. Champagne embraced the danger.

He and his editor, Ed Askinazi, spent 12 to 18 months cutting the Champagne interview tapes into a usable form. Then Sporn tried an experiment, as he wrote on his blog:

I decided the next phase should be to start animating. I’d made a lot of decisions — based on the track — in my head, and I had designed a character. There was no storyboard. No storyboard reel/animatic. All there was was a soundtrack (which I had, by this time, memorized). I simply started animating and coloring as I went through the soundtrack.

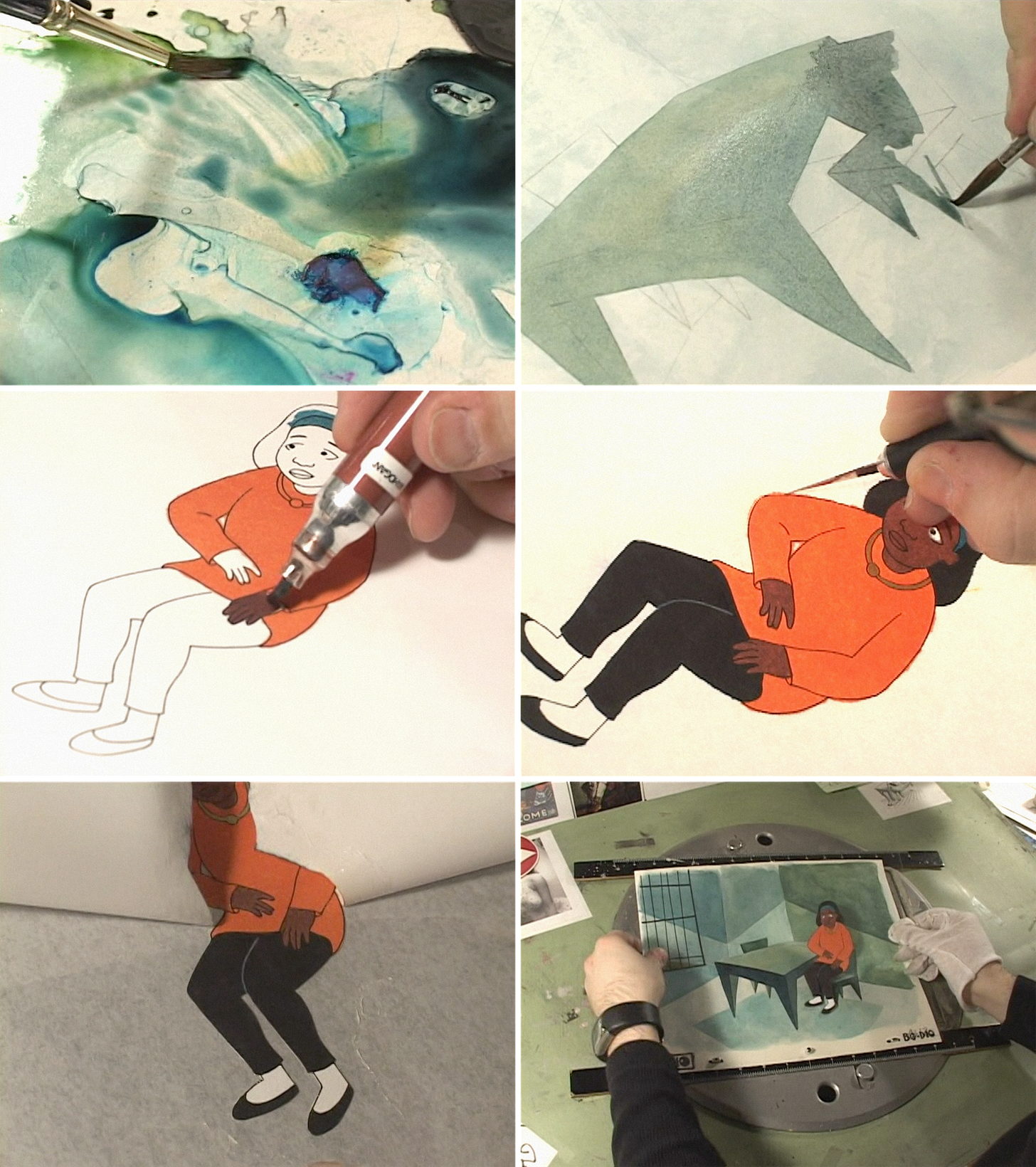

He animated around half of Champagne in this purely improvised way. Sporn drew on paper with ink rather than pencil — a rare technique used by the New York animator Ed Smith. And, instead of starting with key poses and in-betweening them, Sporn worked “straight ahead” by crafting one frame after the next. Here, he followed in the footsteps of his mentor, Tissa David.

The results have the rustic, inviting feel typical of Sporn’s drawings. Champagne often moves “on threes” (or even lower), and it doesn’t fight so-called mistakes. But the simplicity is deceptive. Few animators anywhere could put as much human warmth into gestures and facial expressions as Sporn did here, even working with more and tidier frames. He was a master of his means.

Sporn’s team brought his animation to life with nontraditional rendering methods. The characters in Champagne were drawn on paper, colored with markers and then cut out and pasted onto transparent plastic cels. This cutout technique was common at the studio. Sporn explained that it “enabled us to use pastels, or colored pencils, or watercolors, or magic markers, and just a whole variety of different media.”

Meanwhile, according to The Animation Bible, the backgrounds were “made with watercolor and Prismacolor pencils.” All of them were laid out and painted by Jason McDonald, a trusted Sporn collaborator. He gave the film a modernist style of design, citing the influence of John Hubley on certain choices. His art leans into grit, texture and imperfection.

McDonald also storyboarded the second half of the film. Sporn, after that initial burst of animation, got sidetracked with other work and fell out of the flow for a few months.6 He asked McDonald to plot out the rest. As Sporn wrote:

He brought a completely different direction to it, and it allowed me to open up and improvise on his methods. I bought myself — and the Champagne character in the film — a security blanket to fall back on. I’d bet no one watching the film can tell where Jason’s work started, but I think the outside alteration gave more depth to the animation I was doing. A change for me and the character.

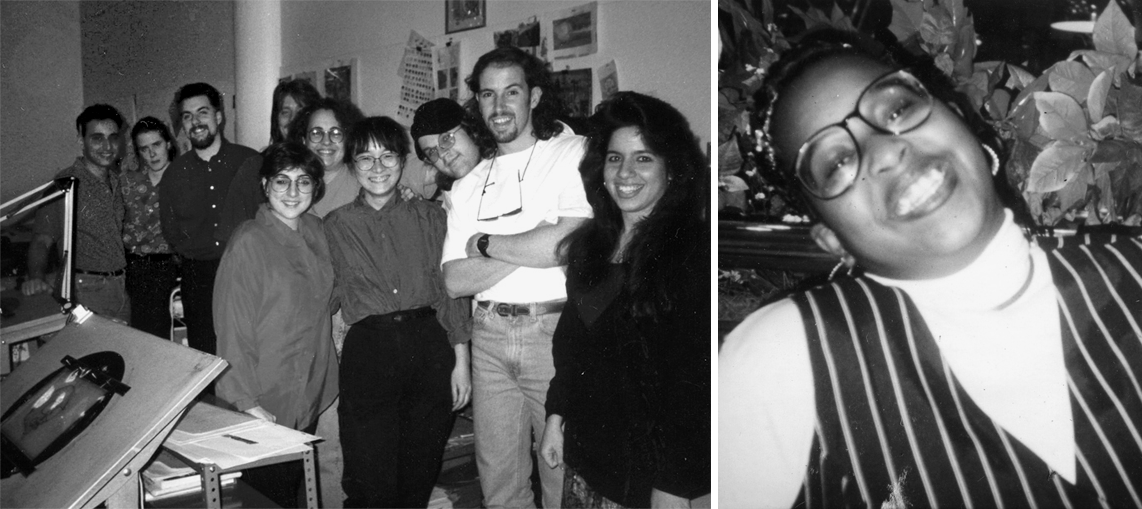

Another member of the Michael Sporn Animation team during Champagne was Champagne Saltes herself. She was in high school, and she interned with them “for about 12–15 months,” Sporn wrote — helping with the colors and doing small assistant jobs.

It emphasizes just how local and unique to New York this project was. Sporn and the team were New York artists helping Champagne to tell her New York story. It wasn’t from the headlines — it wasn’t a stranger’s life. It was a documentary about someone so nearby that she could spend a year or more working with them in person.

Champagne (watchable above) is raw and real — in many ways dark, but not sensationalistic. It’s messy and complicated like life tends to be. As Sporn noted, “Nobody wanted to put it on television at first.”

But Champagne and her strong, down-to-earth message of hope proved hard for critics and viewers to resist. The documentary won a slew of awards, including Best Film at the 1997 ASIFA East festival in New York. Sporn said that it performed “very well in the nontheatrical educational market,” too. This risky, low-budget side-project became one of the studio’s most acclaimed films.

It still commands your attention today. Champagne may be obscure now, but, like with most Sporn projects, that has more to do with availability and visibility than it does with quality. The 14 minutes you set aside to watch Champagne Saltes’ story aren’t, and never will be, 14 minutes wasted.7

2 – Newsbits

Under the Onion Skin, the great podcast, is back with another season. Its latest episode is a conversation with Jadwiga Kowalska of Switzerland about her film The Car That Came Back from the Sea.

Scavengers Reign, one of the best American shows this decade, has been canceled. Co-creator Joe Bennett shared a fully animated teaser of “what was going to come in the second season.”

Skwigly commemorated 50 years of Roobarb, the British children’s show, by delving into its history and sharing its pilot.

More news from Britain: Aardman’s Over the Garden Wall short got a behind-the-scenes video.

The American movie The Wild Robot has earned $292 million worldwide. Per Deadline, it’s “now surpassed Encanto overseas.”

A long interview with a prominent Westerner in Japan’s animation industry, Federico Antonio Russo, gets into the realities of the anime business.

In Australia, a study suggests that YouTube’s and Netflix’s algorithms are deciding what kids watch — and sidelining work made in and about Australia. Kidscreen noted that children “sometimes assum[ed] that even their favorite Aussie shows … were American.”

Leon and the Professor, a Nigerian film co-produced with France, has hit the festival circuit. See a clip (and photos of the premiere) here.

Olivia & the Clouds, made in the Dominican Republic, screened at a major festival in Tokyo. Its director was on hand to discuss its process, how he taught himself animation and how he trained members of his own team.

In America, a new PBS series called Carl the Collector draws from Peanuts and the Fuzzytown books by Zachariah OHora, who created the show. Director Lisa Whittick said, “We try to show kids as they are and not try and sugarcoat relationships and make it all happy and fun.”

Until next time!

From The Making of Champagne and Whitewash, included in a box set called The Films of Michael Sporn. This is one of our key sources.

Champagne’s mother served a decade for manslaughter, and was released in 1994, a few years before Champagne premiered. She got involved with the STRIVE program after release and started to put her life back together.

Detail from a New York Times article about the nuns.

From the director’s commentary on Champagne, as heard in The Films of Michael Sporn. Another important source.

From this blog post. Just a few scenes in Champagne were animated by Sporn’s co-workers, such as the bus heading to the prison (by Jason McDonald) and the line-drawn zoom through the hallway toward the start (by Matt Sheridan).

Today’s feature is a revised reprint of a story we first ran on March 30, 2023. It felt like the right time to bring it out from behind the paywall.

Champagne was fantastic and I loved the idea beyond the name My Mother's House.

Always enjoy your notes and definitely need places that can serve as an oasis in these parched times.....thanx

Stories like this are why I'm so glad we have Substack in the world; it's great to have a name to attach to my most hazy PBS memories! Keep up the amazing work!