Welcome! It’s a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing this Sunday:

1) Greats from Japan on the animation they loved.

2) Newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – The favorites of your favorites

Anime is dominant right now. It’s hard to find animation anywhere that isn’t influenced, at least a bit, by ideas from Japan. That’s the case in character design, acting, pacing, staging and more.

And it’s been the case. Last year, a Disney veteran recalled the pitch for Ariel’s look in The Little Mermaid (1989). “What if we did our own version of an anime girl character?” Glen Keane reportedly asked. Hayao Miyazaki’s work helped to inspire her design.

But Japanese animation didn’t appear in a vacuum. When its creators came into their own during the ‘60s and ‘70s, their ideas had reference points as well. A Japanese magazine, Manga Shonen, revealed a few of those reference points in 1978.1

It surveyed Japan’s animation scene, asking people about their favorite animated works from across the globe. Miyazaki, then a young director in his 30s, responded with two. First was The Snow Queen (1957), a Soviet classic. He’s borrowed from its characters throughout his career. In a way, you could argue that Ariel started there.

But his second choice was a curveball. He named Panda! Go, Panda! (1972), an Isao Takahata film on which Miyazaki himself had worked. Later, it became fuel for My Neighbor Totoro.

The survey holds a lot of surprises like that one. Manga Shonen looked well beyond Miyazaki — getting answers from his seniors in the industry, from artists at rival studios and even from the independent world. It captured a cross-section of Japanese animation at a critical time: the start of the “anime boom.”

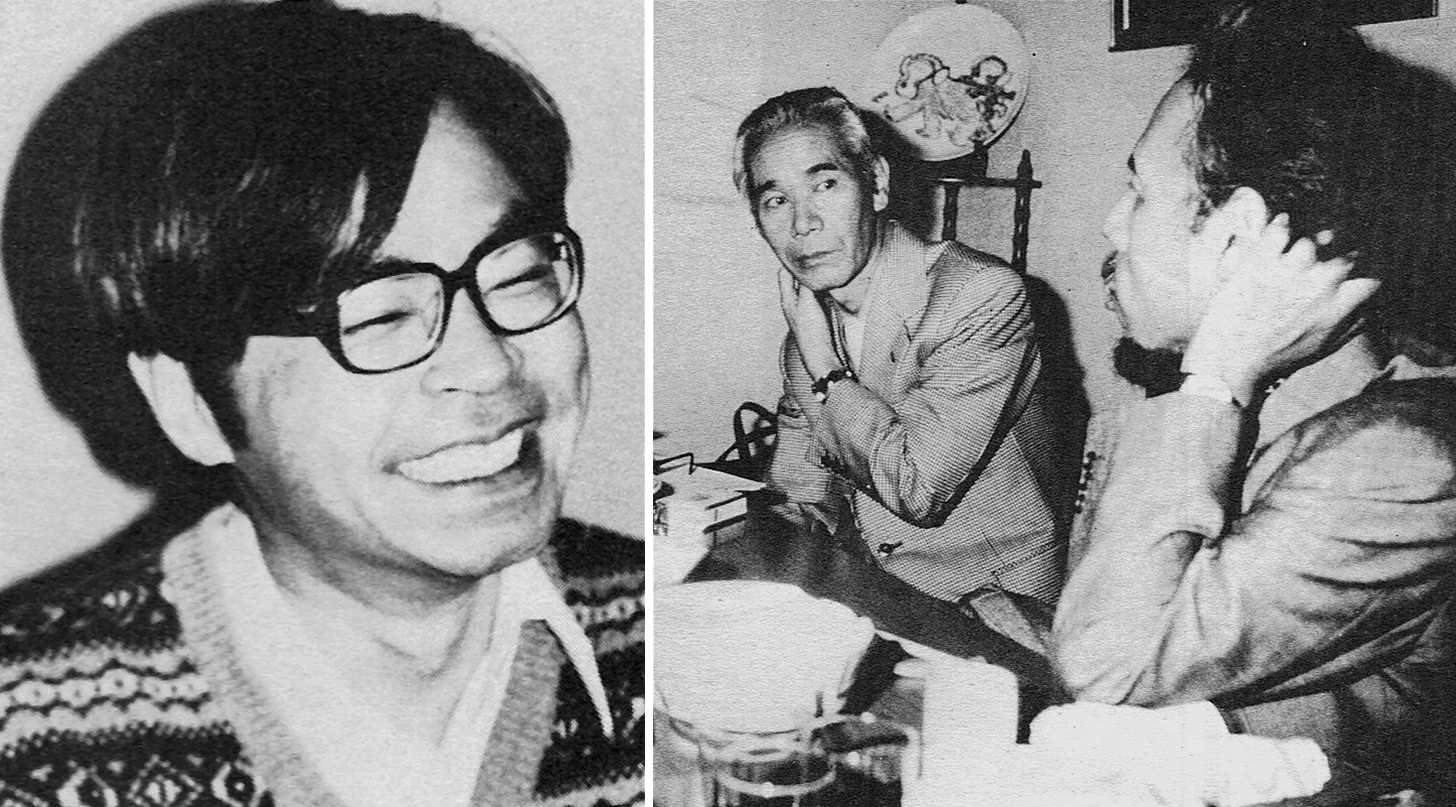

No film gets more credit for the anime boom than Space Battleship Yamato (1977), also known as Star Blazers.2 Its success excited investors and broadened the industry. Plenty more Yamato movies followed. So, it’s fitting that Manga Shonen opened its article with the answers of director Noburo Ishiguro, who played a major role in that series.

Ishiguro’s work wasn’t like Disney’s, but he confessed to being a “Disney fan.” Snow White (1937) was his pick from the studio. His other favorite animation was an experimental short by Norman McLaren: Neighbors (1952). “This is something I saw when I first became interested in making animation using 8 mm film,” he wrote. He knew cels — seeing this type of stop motion flipped his world on its head.

In general, quite a bit of love for Disney turned up. Snow White got mentioned several times. The director of Toei Doga’s Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963) chose Bambi — as did Akira Daikubara, one of Toei’s essential animators. “This work showed me the wonder of feature-length animated films,” he noted.

It wasn’t just Toei. Even more Disney fans came from the rival Mushi Production. Take director Osamu Dezaki (Ashita no Joe), whose style helped to set the template for boys’ action anime from then on. Snow White was the only film on his list.

“I’ve been crouching in front of that ‘high wall’ for years now, pulling up weeds,” Dezaki wrote. “I wonder if there might be a mole hole that would allow me to get through to the other side...”

Another ex-Mushi artist, Junji Kobayashi (Jumping), put it bluntly:

If you think animation is best represented by Space Battleship Yamato or Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, you’re very mistaken; the work I would like young fans to see is Fantasia.

There’s a misconception now, though, that Disney was the only thing Japan’s animation artists eyed in these early decades. The Manga Shonen article shows otherwise. Artists of that era loved a range of films. Some of those films are little known today — and many of them were unavailable in Japan outside film clubs.

After Fantasia, Kobayashi filled out his list with Fleischer’s Mr. Bug Goes to Town (1941), which Miyazaki idolized at the time, and arthouse shorts like The Creation.3 Some people cited Popeye and Road Runner cartoons. Shinichi Tsuji, later a director on the ‘90s Superman animated show, praised Raggedy Ann & Andy.

And certain artists in the survey weren’t Disney fans at all. Miyazaki preferred Fleischer, for example.4 His former co-worker at Toei, Reiko Okuyama, was even further outside the mainstream. “Disney’s and Fleischer’s works are very interesting when I see them, and I admire their technique and so on, but I don’t like them that much,” she wrote in her section.

Okuyama was an animator and designer who worked in the industry and yet didn’t feel at home there. She was important to Toei’s Horus: Prince of the Sun in the ‘60s, and went on to be a Grave of the Fireflies animator, but she ultimately switched careers to do personal art. Among her favorites were The Snow Queen, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1959) and The Hand (1965) — the latter two by Jiří Trnka, the Czech master of puppets.

She also had kind words for a pupil of Trnka’s — the Japanese animator Kihachiro Kawamoto. He’d traveled to Czechoslovakia in 1963 to study stop motion. Kawamoto returned to Japan as The Hand was being prepped, and he became a force.5 Okuyama enjoyed his independent film Dojoji.

Kawamoto himself replied to this survey, selecting The Hand and The Metamorphosis of Mr. Samsa by Caroline Leaf. That second film had just come out, but he wrote that its visual ideas were “wonderful.”

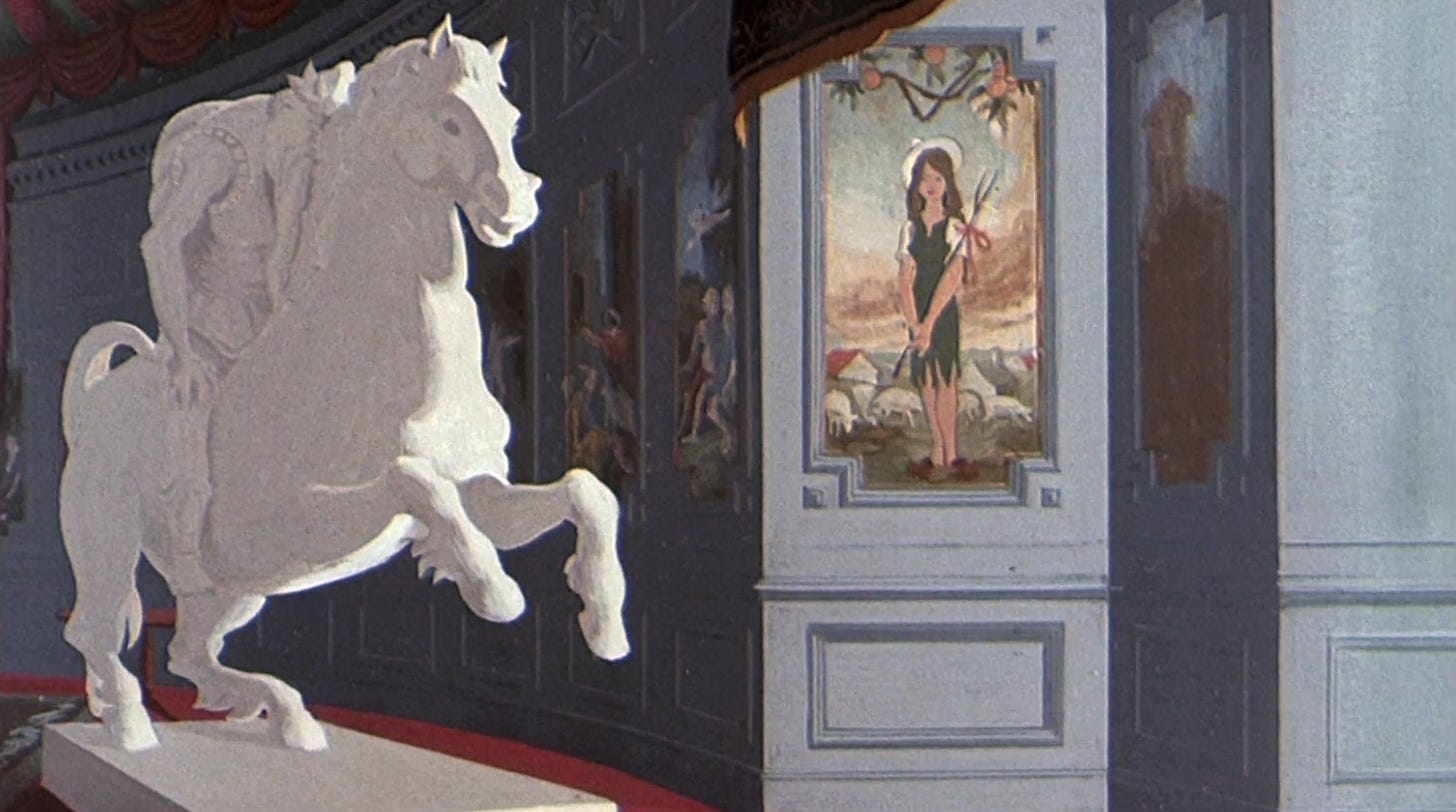

One other movie needs to be addressed. It looms over the article — brought up more often than Snow White. For some in Japanese animation, it was bigger than anything by Disney. That was The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep (1952), released in Japan as The Cross-Eyed Tyrant.

Shepherdess is a French film, and it’s wholly unique. The Toei Doga people were stunned. Isao Takahata joined Toei because of it, and Miyazaki and Yasuo Otsuka were hugely inspired by it.

Okuyama, who remembered Shepherdess as “really fresh,” included it in her list. So did Yasuji Mori — a core animator from Toei, a mentor to Miyazaki and maybe the most legendary artist in the survey. Shepherdess was his first pick (followed by Disney’s Old Mill, Takahata’s Heidi, Little Gray Neck from the USSR and The Spider and the Tulip).

Elsewhere, animator Kazuko Nakamura dedicated the longest write-up mostly to Shepherdess. It was her influence and, like with Takahata, her main reason for joining Toei in the ‘50s. “When I was an art student, I was a cinema buff and would go to the movie theater whenever I had a chance,” she wrote. “During that time I came across this film The Cross-Eyed Tyrant, and it was a great shock to me.”

Nakamura moved to Mushi in the ‘60s. Even there, Shepherdess was wildly popular.6 Then she got involved in Osamu Tezuka’s film Tales of a Street Corner (1962), her other favorite.

That’s not the last of the intriguing stuff in this article. For example: several people chose Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958), the first big Toei Doga production. Producer Tatsuo Shibayama placed it alongside Astro Boy and the Goofy and Donald Duck cartoons. Artist Katsuhisa Yamada, who went on to direct The Last Unicorn (1982), named Panda, Fantasia and Horus. And so on.

Sometimes, anime gets treated like a monolith whose only reference point is itself. The reality is more complex. Especially back then, this was a world of dueling creative processes and ideals — where many artists were, like Dezaki, trying to climb the “high wall” of their own outside influences. As Miyazaki once said:

I entered into this industry because I saw works in the 1950s, such as Cross-Eyed Tyrant or Snow Queen. I thought maybe I could manage (to reach the level of) [Panda and the Magic Serpent] but anyway, I thought they were far above, in terms of what they tried to do, and what they accomplished. We were, in short, at the level of “Toei kids’ stuff.” The gap between our level and the works we were inspired by was too big. We thought how could we climb up there, or even if we couldn’t, let’s remove the stones around us. So, there were many things we had to do.

The work that Japan’s animation people made would, eventually, take over the world. But there’s value in knowing where it came from. In some cases, there’s no better way to understand your favorite artists than to explore their favorite artists.

2 – Newsbits

Recently, we lost animators Emma Calder from Britain and Susie Wilson, as well as Doc Harris (the English narrator of Dragon Ball Z) and Nobuyo Oyama (the original voice of Doraemon).

Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano (Angel’s Egg) is doing short animations of his own and posting them on social media.

In Zambia, animator Tabitha Mwale spoke about her journey and the growth of animation in her country. “There is a small demographic of animators,” she said. “Very few. I would say under 10 people do it professionally.”

Kiri and Lou, a beautifully animated series from New Zealand, is getting a feature film. Its name: Kiri and Lou Rarararara!

In Japan, Dwarf (Pokémon Concierge) has a new short coming. It’s called Komaneko, and it looks like fun. The studio continues to be one to watch.

Also in Japan, Financial Field compared animation’s biggest box office hits of the Heisei era (1989–2019) with those of the current Reiwa era. In the first group, four of the top five came from Ghibli. In the second, four of the top five are franchise films. The outlier on both lists? Makoto Shinkai.

In Russia, the Cinema Fund revealed the latest animated projects to receive state support. Not on the list: the new film from Andrei Khrzhanovsky (Glass Harmonica), who’d applied for another round of financing.

The Chinese director Busifan is bringing his project The Storm to Russia. It’s the opening film at the Big Cartoon Festival (the country’s largest). Also screening there: To the Bright Side, an amazing Chinese anthology that almost no one has had the chance to see in English yet.

One more from Japan: director Kenji Iwaisawa (On-Gaku) is hosting a live event just to create rotoscoping material.

Lastly, we looked into the longstanding ties between Russian animator Yuri Norstein and Japan.

Until next time!

The main source for today’s issue is Manga Shonen (October 1978). We have to thank researcher Tim Eldred, who runs an incredible site dedicated to Space Battleship Yamato, for his help in providing us with this article.

The Space Battleship Yamato movie was a recut version of the TV series, which was itself recut into Star Blazers in the United States.

In the late ‘70s, Miyazaki praised Mr. Bug and called it the best example of the “cartoon movie” (manga eiga) style during his interview in Future Boy Conan: Film 1/24 Special Issue. He seems to have soured a bit on the film by 1980, based on his Fleischer essay collected in Starting Point.

Miyazaki explained this in his Film 1/24 Special Issue interview.

Kawamoto mentioned that The Hand was in the planning stage on page 319 of Czech Letters & Czech Diary.

The love of Shepherdess at Mushi was discussed by researcher Seiji Kanoh in this article.

And “The King and The Mockingbird” was directed by French director Paul Grimault - interesting to note (to me at least) that the French live-action director Jacques Demy (Umbrellas of Cherbourg) worked briefly under Grimault following an early desire to be an animator, recreated in early parts of his wife Agnes Varda’s biographical film “Jacquot De Nantes”.

Also interesting in Grimault’s film is the appearance of a giant robot and I wonder how much this inspired the giant robot trope in Japanese animation.

Absolutely wonderful writeup. Seen many of these animated films several decades back. Now feel like watching them again. They are always evergreen.