Welcome! It’s another Thursday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Today, we’re continuing our chat with animator Tony White.

We published the first part of this interview back in May (here), and the response was wonderful. In it, Tony reminisced about London’s animation scene of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when he worked at Halas & Batchelor and Richard Williams Animation.

Back then, Tony contributed to A Christmas Carol (1971) and studied under famous American animators like Ken Harris and Art Babbitt — who taught Williams’ team. It was tough but rewarding work, and it helped to take the studio to the top.

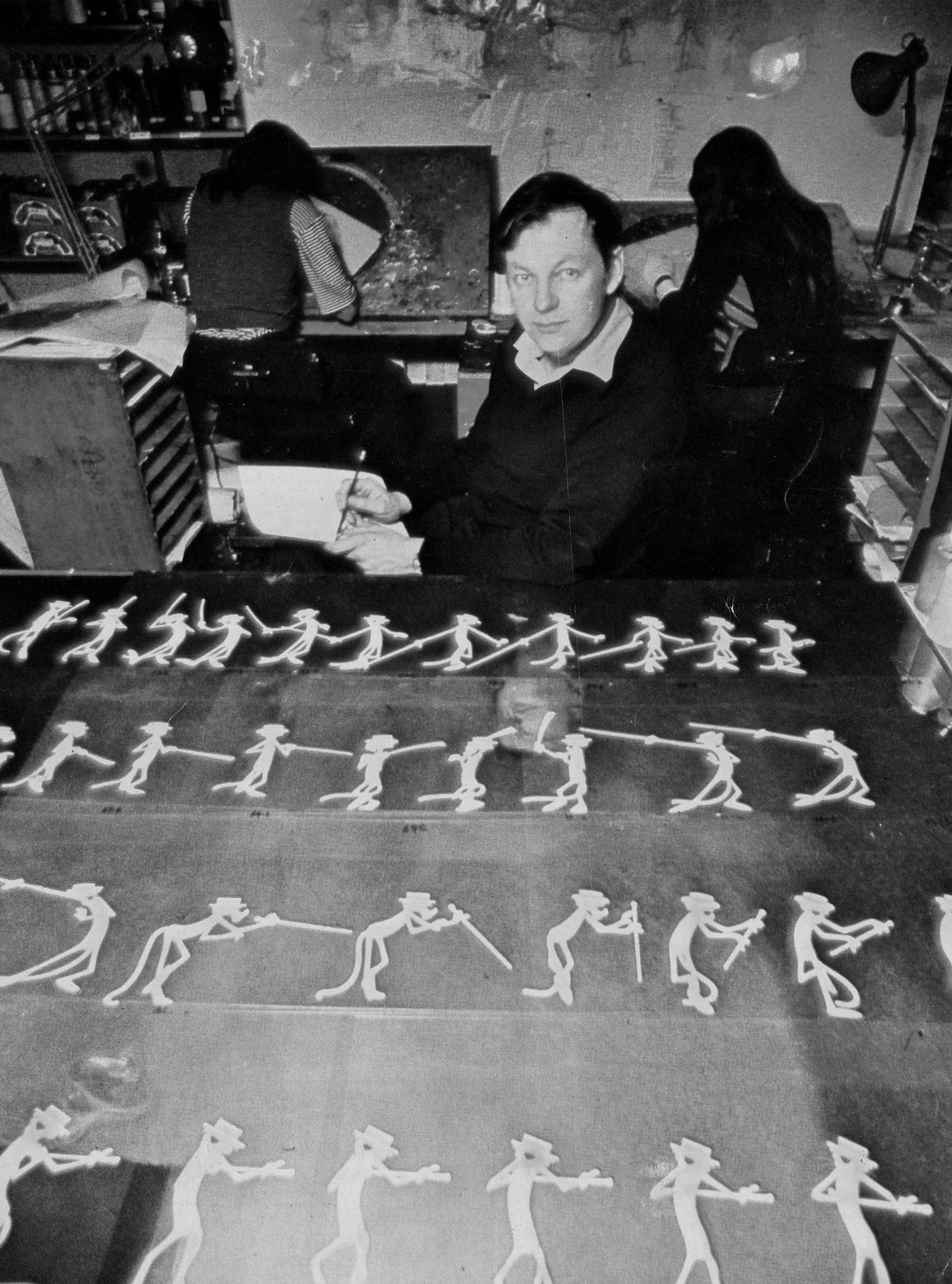

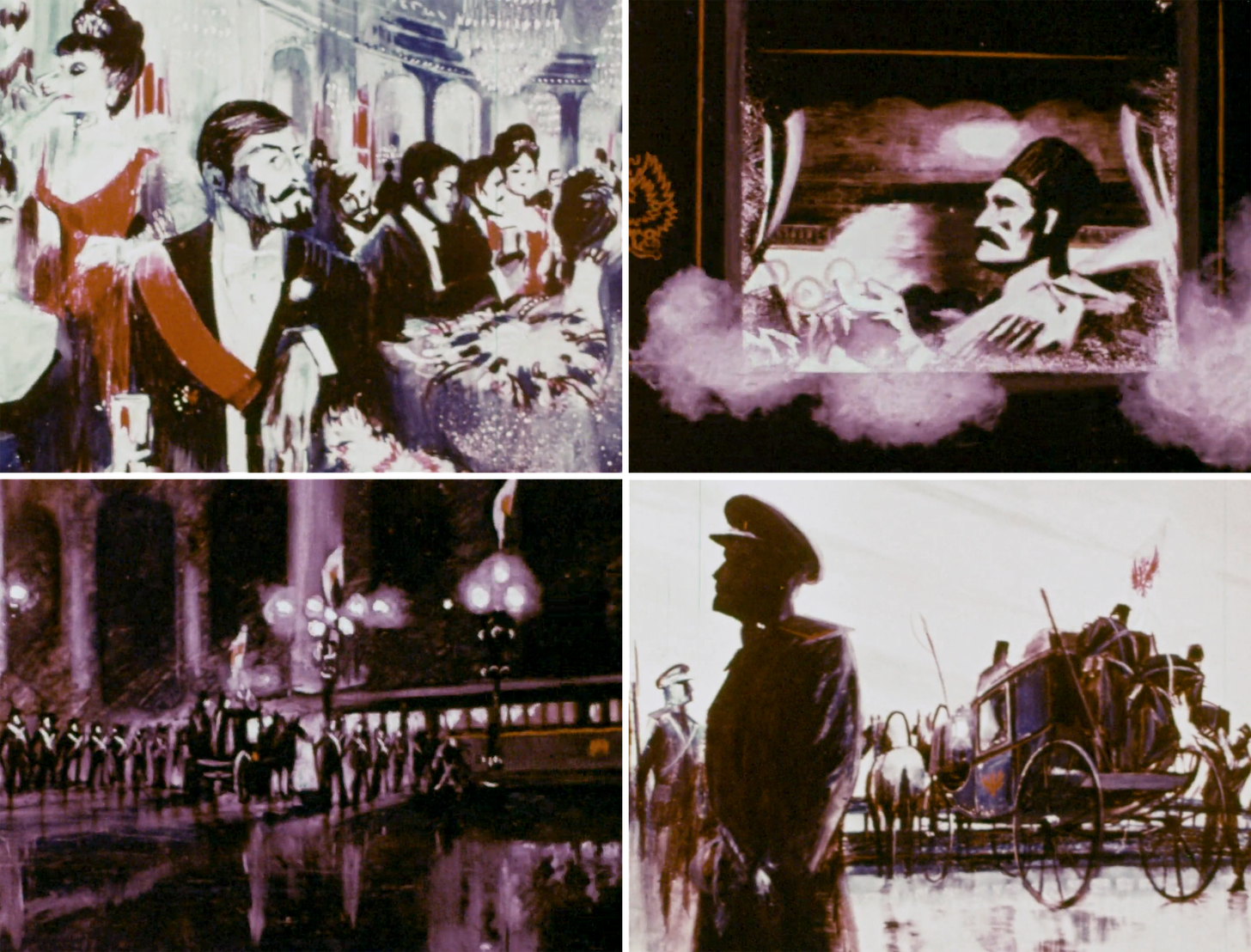

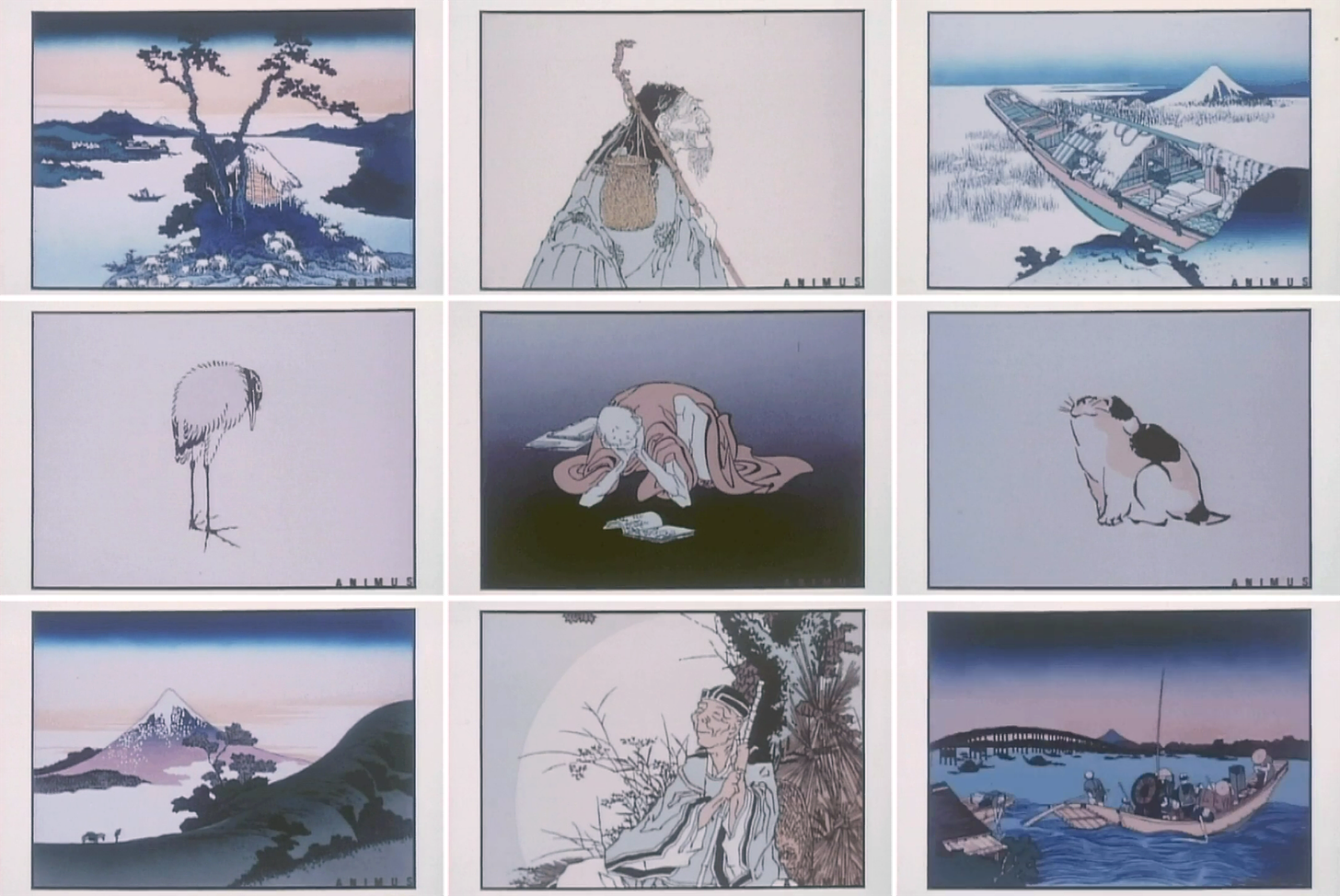

In part two, Tony speaks more to our teammate John about working with Richard Williams: the studio’s dominance, its unsung talents, its reputation in London and the wild story behind the opening titles of The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976). Meanwhile, he goes deeper into his personal film Hokusai (1978), why he left the studio and why he moved to the States.

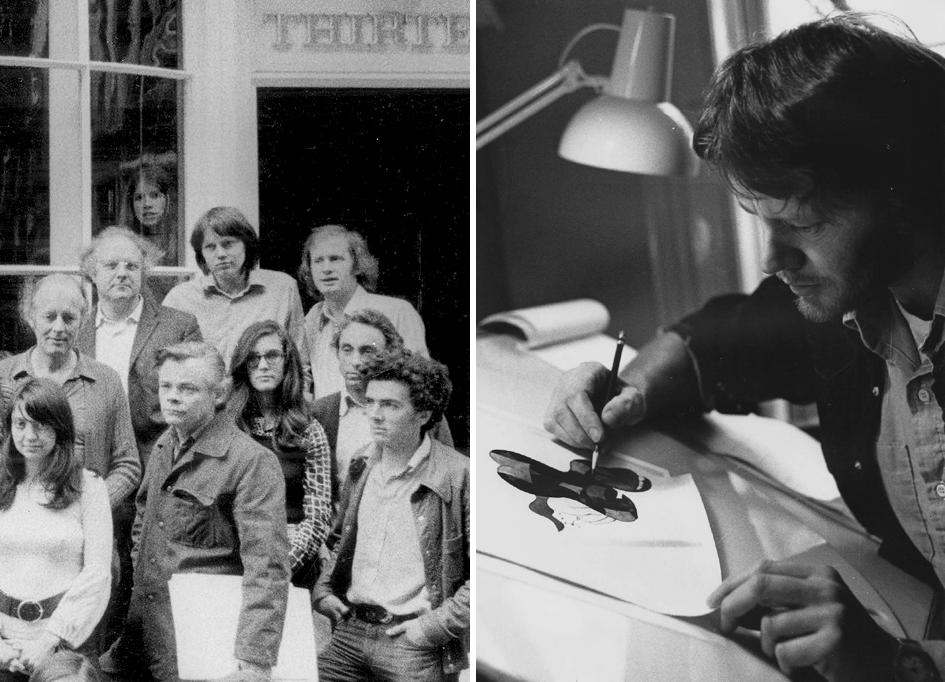

Since it only comes up in passing during the chat, it bears mentioning here that Tony led a highly decorated career in TV and ads after parting with Williams. His studio Animus, which ran from ‘78 to ‘98, made ads like Bear and (with Aardman) Rousseau. Since then, Tony’s spent a lot of time writing and teaching. Right now, he runs 2D Academy and is planning an animated memoir, The Old Man Mad About Animating.

Below, the conversation (edited for flow, length and clarity) continues. Here we go!

John (Animation Obsessive): The Richard Williams studio worked in a billion different styles. Were you guys watching the other animation from around the world? Was that being screened there?

Tony White: No, no. I don’t know if you’ve heard this, but Richard Williams’ studio was known by the rest of the London industry as “the monastery.” In other words, we were just isolated. We were like monks — we’d never go out into the world and see anything. I mean, it did happen, of course. But, basically, that was the perception in the industry.

I have to admit, there was an elitist attitude. And I’m sure Disney and the Nine Old Men had an elitist thing in Hollywood. They felt, “We’re pushing the barriers here; we’re going further than anyone else. So, we’re pretty good.”

Although in Dick Williams’ studio we weren’t arrogant as such, we tended to feel we were doing the good stuff. As time went by, others came in and did good stuff, too, and raised the whole bar. But, for a period of at least two or three years when I was there, the Richard Williams studio would win more international awards for its work in the advertising world than all the other studios put together.

John: Wow.

Tony: It was so dominant. We were doing commercials for pretty much every country around the world that had the budgets to afford it. Certainly America and big pockets of Western Europe. Sometimes Australia; sometimes other places. People would come just to have the work done there.

The impression we got was that the rest of the industry resented the Richard Williams studio. They weren’t nasty to us. If they spoke to us, they were really nice. But I heard stories, and that’s why it was nicknamed “the monastery.” We were considered aloof to everyone else [laughs]. And we weren’t really. Just, I don’t think Dick would tolerate you if you were a pub guy. Not to say he didn’t drink and everything, but he wasn’t into the pub scene and he didn’t want people from that era.

He was always flying to Disney and talking to people and getting information and coming back. The Disney people would tell him, “You just want the good, meat-and-vegetable family guys. You want somebody with a wife and kids who doesn’t go out drinking or partying, who’s loyal and does their job in a really good way.” And that seemed to be the kind of people who worked there.

There was a pub called the Dog and Duck, which was in the Soho district of London. It was considered the “animators’ pub.” Everyone would hang out and chat. I wasn’t a pub guy, but I don’t know if any of Richard Williams’ employees would go there. That would be the most likely place to congregate, if they did.

John: That’s fascinating. So, I’ve got a question written down here: what’s your favorite story to tell about your time at the Richard Williams studio?

Tony: [laughs] There’s some I can’t tell.

Years later, I went to the Kalamazoo Animation Festival and met Eric Goldberg. He worked with us — he was one of the team in my time there. I was the first one to leave and set up my studio, and then gradually others drifted off. He went off and became part of Passion Pictures, and then ended up at Disney.

But I met Eric and we went to dinner. He told me he was writing a biography of Chuck Jones. I said, “That’s fantastic.” He was all excited about it. I said, “You know what you need to do after that, Eric? You should write a biography of Dick.”

And he looked at me straight in the eyes and said, “Tony, I couldn’t afford the lawyers.”

John: [laughs]

Tony: Because there are so many stories that you could tell. But I don’t know. What’s a favorite story…? Meeting Frank Thomas was an amazing thing.

I don’t know so much about stories, but I’ll tell you one thing that kind of frustrated me. In all honesty, in my opinion, the greatest animator-artist at the Richard Williams studio was not Dick himself. He was great — I mean, he was amazing, incredible. But, for me, one of the young team there, Russell Hall, was the greatest animator-artist that worked at Dick Williams’ studio. And he never got the credit for it.

He was kind of an anonymous character anyway. I wouldn’t say shy, but he didn’t like attention. But Russell was a genius. I heard that he did the final design of Jessica Rabbit. I wasn’t there, so I don’t know.

Apparently, Dick drew most of the original characters, but he could never nail Jessica Rabbit. It was getting tight with the deadline and everything. The story I heard was that Russell was working there and heard that they needed this. He walked in the room and said, “How about this design?” And Steven Spielberg said, “Love it. Love it. That’s Jessica Rabbit.” And that’s what they went with. Now, I don’t know if that’s true, but it would be true of Russell.

He wasn’t really a cartoonist artist. He did some amazing… if you look up the Shell commercial with the oil rig in the middle of the ocean. And there was a Vodka commercial done in a very impressionist style — with lots of dissolves and everything. Very simplistic but beautiful imagery. He would do all that stuff.

He was my favorite animator there. So, I don’t have a favorite story for you, but I have a favorite opinion. Russell was the most unheralded, greatest artist at the studio.

John: That’s awesome. He’s not on my radar — I’ll have to look him up.

Tony: The last I heard, he was living a life of seclusion with his wife, Carol, who was Dick Williams’ secretary. They got together and married. What I hear is that he’s in France, living the life of a reclusive painter.

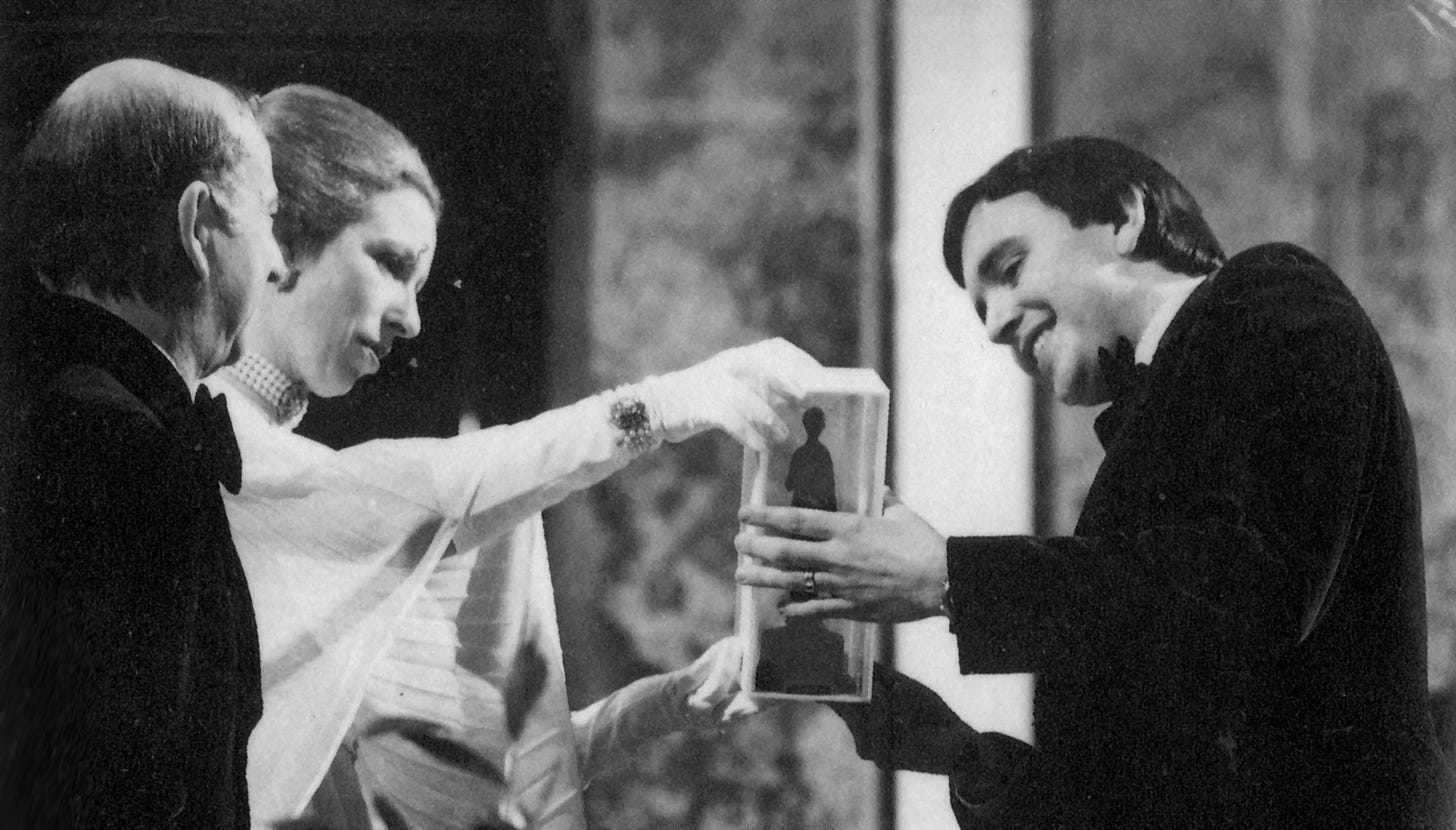

John: You ended up doing the title sequence for The Pink Panther Strikes Again. How did you get assigned to that?1

Tony: So, Dick had done The Return of the Pink Panther with Ken Harris. I’d assisted Ken and worked on a little bit of it. And Dick had promised the movie director Blake Edwards, “I’ll do the next titles. Definitely.” It was a drunken promise at the celebration party when the movie was finished. Blake Edwards said, “Yeah, I’ll hold you to that, Dick. I’ve got witnesses.”

As it turned out, when the second one emerged, Dick was committed to directing the Raggedy Ann and Andy movie in New York. So, Carl Gover, the producer, came to me and said, “Dick asked if you would do The Pink Panther Strikes Again.”

In fact, you asked about a story. This is a good story.

I think it was being filmed in Shepperton. I met Blake in his private apartment there and showed him my work. He said, “You’ll be great for this.” I said, “Well, what do you want, Blake?” He said, “The titles are totally yours. Just have fun with the Pink Panther and Clouseau. Here’s the script.”

I told him, “I’ll come back with a storyboard in a week’s time.” That’s what I did — I went away, read the script. And I thought, “Okay, I’ve just spoofed film sequences. Hopefully he’ll love it.” I went back a week later and sat in his private apartment. I had the drawings on his coffee table, and he was sitting on a small, backless stool next to me.

There was one sequence that made me very nervous, because it was a spoof on The Sound of Music — Julie Andrews. Blake Edwards was married to Julie Andrews. And he was a very stern-looking guy, really scowly-looking. He wasn’t like that at all, but this was my first impression. I thought, “Oh, God, he’s gonna...”

So, I was flipping through the storyboard, and I got to the Julie Andrews part. I said, “I’m going to do a spoof on The Sound of Music,” and turned the page very quickly. He said, “Hang on. Turn back. What was that?”

I turned it back to the Julie Andrews storyboard sequence. He just stared at it with this scowl on his face — like, for a minute. It was so embarrassing. I didn’t know what he was gonna say, what he was gonna do. I thought, “I think I’ve blown it.” And then, eventually, he burst out laughing.

He was laughing so hard, he fell off the back of the stool he was sitting on — to the floor.

John: [laughs]

Tony: He said, “Go do it! I don’t want to see any more. Just go do it!” I had 12 weeks, basically, to do two minutes or something.

I said, “The only problem is, we need the music to choreograph the action to.” And Blake said, “Henry Mancini is gonna come and do the music after you’re supposed to finish this. What can I do to help?”

I asked, “Can you consider a friend of mine, Howard Blake? I think I could get him to score the whole thing, and we’ll pre-record it. Then, when Henry Mancini comes over, can he just reproduce Howard’s music with a full orchestra?”

Bottom line is, Howard composed the whole title sequence, and arranged for six of Henry Mancini’s favorite London musicians to record it in the studio for me. They were part of his big orchestra in London. We sent it to him, and he totally loved it. He said, “Oh, this is great. In fact, I’m kind of busy. Do you think Howard could score the movie for me? I’ll come and conduct it. But he can’t have the credit — I have the credit.”

So, that’s the story, right? And it goes on a bit. Howard Blake composed all the music for The Pink Panther Strikes Again, and I got sick at the end of it, so I couldn’t go to the recording session. Howard went along and met Henry Mancini.

Now, Howard is classically trained as a musician and a concert pianist. He scored this whole thing. And Henry Mancini allegedly couldn’t read the score. It was far too complicated for him. So, he said, “Howard, I can’t credit you, but could you conduct it?” And so Howard conducted it as well. I wasn’t there — that’s what I was told.

John: To circle back around to Hokusai, you apparently started working on it right after Christmas Carol?

Tony: Yeah. Like, the next Monday [laughs].

John: What was it like making the film over that long period of time?

Tony: Yeah. Five-and-a-half minute film, two-and-a-half years in production.

Occasionally, I’d get breaks at Dick Williams’ studio, where I could work on it between commercials. But I’d go home evenings, weekends, any vacation times, like Christmas and Easter — just any time I could work on it. It was horrible for my family [laughs].

There was a wonderfully weird thing in the UK at that time. They incredibly supported artists, animators, filmmakers and everything, and they would try to ensure that the best of British work was seen in festivals around the world.

They heard about Hokusai, and they said, “Can you have it finished by this date? It’s beyond the deadline, but we can get you access to the [Zagreb animation festival]. We’ll put it in a diplomatic pouch. One of our guys will fly over there and deliver it, because we want it in Zagreb.” And I said, “Well, I can try.”

I took three months off, unpaid, to finish the film. It literally did go off in one of those diplomatic bags, which means it doesn’t go through immigration or anything. They take it straight through. So, it was an amazing experience.

Working at Dick’s studio, you knew very quickly that animation wasn’t “cartoon films.” It wasn’t for kids; it was art, moving. Yeah, we did cartoons, and I loved it. But I’d always felt that way — when I was at Halas & Batchelor, I thought, “I want to push animation into new areas.” Hokusai was my first statement in that direction.

With the success of Hokusai, I went off and set up my own studio. Not because I wanted to set up my own studio, to be honest.

John: Was Hokusai a totally solo film?

Tony: Yeah — it was totally, pro bono me. I did everything on it for free.

Towards the end of it… you know, we got paid, but we didn’t get paid well at the Richard Williams studio. Not super well, anyway. I couldn’t afford the music, the post-production side, the camera filming. So, I went to the British Arts Council, which was a government-funded department in those days, and pitched the project to them and asked if they would give me the funding for the final aspects. They agreed to that.

The downside was, in accepting their money, they took ownership of the film negative. It was stored at the British film archive — the BFI, British Film Institute, has a big archive of British films. They actually own the film. But, with them, I was able to finish it.

So, it was totally done by me, but I needed that help at the end.

John: As somebody who was very much part of it, how would you describe the state of British animation as a whole in the ‘70s and into the ‘80s? What was the situation like in general?

Tony: If I put my Richard Williams, arrogant-studio hat on, we definitely felt we were the best studio in London. Because of the influence and the opportunity we had to study with the great Hollywood animators. However, we also respected really well-made original films like The Snowman, for instance. And always chuckled at Bob Godfrey films.

But, in general, I think our minds were focused towards feature films at a kind of Disney level of production. The British animation scene was always not that. It was a frustration therefore that we never, in my time there, got any of the movies off the ground.

Dick would turn away a lot of… he turned away Watership Down, which I thought was the worst, most terrible decision ever. With his artistry and our talent, that could have been an amazing film — that really could have been a breakthrough. But he turned it down because he always wanted to work on his own film.

And let me jump back a bit. I said earlier on that I didn’t really want to leave Richard Williams’ studio, because it was the best. I mean, where are you going to go? Even if I set up my own, it’s never gonna be that, in my mind.

The reason I left was, after I did The Pink Panther Strikes Again and it got awards and kudos, I went into Carl [Gover]’s office. And I said, “Carl, I really want to do more directing like this, because I think that’s my thing. I’m an animator, but I want to be more than that.” And he said to me, “Tony, you should know by now that there’s only room for one director in this studio. It’s not going to happen.”

And I said, “Okay, then I have to move on.”

I didn’t do it with resentment — I just did it with the reality that it was difficult to get beyond Dick in your own career aspirations. As much as I love him and his work, and he was my hero and still is, I needed to be me and do what I wanted to do. So, that’s why I left.

John: And I’m assuming it was pretty tough starting a studio from zero.

Tony: Well, I was lucky. Here’s another story.

In the hierarchy of English film — and I’m not talking animation; I’m talking about film now — my hero as a producer was David Puttnam. He, to me, was one of the greats. Chariots of Fire, The Mission, Memphis Belle, a number of other films. I’d never met him. The film world wasn’t my scene. But he was my hero.

I’d made Hokusai. And, as I had to leave for my own self-expression, I started looking around for funding and partners. I met a very strong, live-action advertising film company, James Garrett [and Partners], and said, “Would you help me set up my own animation studio as an adjunct to you? I would run it and everything, but maybe you could fund it and use your contacts to get me work.”

We actually came up with an agreement, and I signed. I was a bit nervous about it. One week later, I got a phone call from David Puttnam’s secretary. He said, “David wants to see you.” He didn’t know me; I didn’t know him. So, I went over to his beautiful building in Mayfair or Kensington. Beautiful. I mean, this was a really ritzy part of London. In I walked — there was David Puttnam. My jaw was on the ground like it was when I went to Richard Williams’.

He said, “I saw your Hokusai film and I think it’s fabulous. I want to get into animation, and I want to do that kind of film. You’re exactly what I envisage. Would you like to set up a studio with me? I’m buying the building next door — that would be your building.”

And I said, “David, one week ago, I signed a contract with someone else, and I can’t get out of it.” It was a big moment of regret for both, I think. But, if that had happened, can you imagine?

So, that was my biggest sad moment in my career [laughs]. I said my life is full of lucky things happening at the last minute. If I’d just been a bit more patient in pushing for partners, and setting up my own studio, it would have been a very different picture. But I thought, “I’ve got to get away — I’ve got to do this.”

It didn’t work out, either. I had to end up going alone anyway. Eventually, I worked for a little while with Carl Gover, who broke away and set up his studio. We were called The Animation Partnership. Then we slowly went our own very amicable ways.

That really is the reason I’m in the US. In the early ‘90s, most of the work I was doing in advertising was for America, and I was flying backwards and forwards. I flew to Mexico one time, to Hollywood, to different places — picking up work and going back to London and doing it. But I was getting fed up with that, and all the time I was trying to get my own projects off the ground.

I had this wonderful story, The Adventures of Uncle Lubin, written by a British icon called William Heath Robinson. I wanted to make a film with that. Despite my awards in advertising, despite my British Academy Award for Hokusai, I couldn’t get funding to make movies in England.

So, in 1998, my life had changed and my kids had grown up and flown the nest. I said, “It’s now or never. I’ve got to go to America, because that’s where they make films.” But I didn’t want to go to LA, so I ended up in Seattle. I had to sit it out here for two-and-a-half years to get my green card work permit.

I was on a fast track because I’d won international awards. After I was here for about a year and it looked like it was gonna get going much quicker, September 11 happened and then everything stopped on immigration and citizenship and everything. So, I got through the two-and-a-half years. Finally, we got my green card work permit, and I was all official.

Then I started talking to investors, and I got them interested in setting up a studio up here in the Pacific Northwest. It was going along smoothly, and then Michael Eisner closed the Disney 2D animation studio. And, I swear to you, the industry died overnight. Everyone ran for the hills. Everyone was saying in the industry and the investment world, “Well, if Disney are giving up, we’re not going into it.”

I had to think, “What’s plan B?” And plan B ended up teaching.

John: I mean, it seems like you’ve done some amazing things with your teaching.

Tony: I like to think so. I like to think I’ve helped lots of people. Some of them are in the industry and have done well.

I prefer apprenticing people, because I did that when I had my studio for 20 years. I preferred people coming — like I did with Ken Harris and Dick Williams — to sit and work with me. It’s the best learning experience ever. I think I did that with my studio. And a lot of people became successful in their own right, and a lot richer than me, I hesitate to add [laughs]. But I don’t regret it for one minute.

And, yeah, the books and everything. I just felt I had to give back. I call it passing on the pencil. You know, the industry had given me so much. I just wanted to pass on my knowledge, so that hopefully other people can do it as well. If I can’t make the movies, maybe one of those readers or students can.

That’s a wrap! Thanks for reading. And thanks once again to Tony for sharing his time and memories with us.

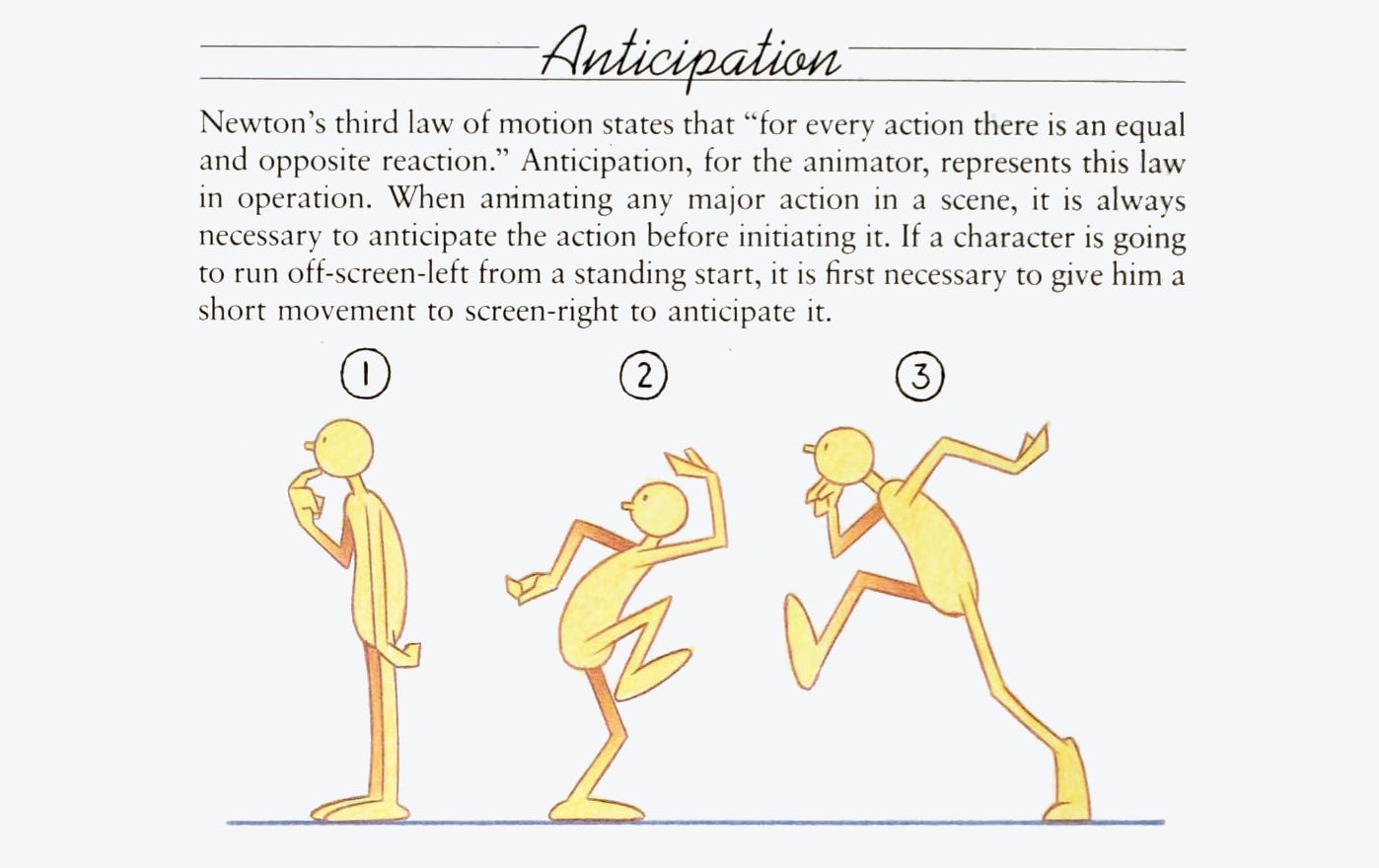

Among Tony’s other books, The Animator’s Workbook was a major one — a success that, in many ways, became the precursor to Richard Williams’ later guide. He’s continued to write since, including The Animator’s Sketchbook (2016), out through CRC. You can see more about Tony and his projects on his personal site.

See you again soon!

A version of this question was on the list to ask Tony, but the conversation naturally drifted to this topic during a segue, without the question itself being raised. For clarity and readability, we’ve added it in the editing process.

This was amazing.

What an amazing interview! All respect for Tony, the man who thought about “ passing on the pencil”